Illustration Sources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annex 3A AERIAL VIEW PLAN

Annex 3A AERIAL VIEW PLAN Plan showing a plot land situate at Bois Sec, in the District of Savanne, of the original extent of +DPò belonging to "LIGNECALISTE PROPERTY COMPANY LIMITED" as evidenced by Title Deed transcribed in volume TV 8272 no.23 Scale 1:12,500 Date: December 2011 Annex 3B CONTOUR/TOPOGRAPHICAL PLAN Annex 3C FLORA & FAUNAL SURVEY REPORT Report on Terrestrial Flora and Fauna at Proposed Golf Course Site at Bois Sec Introduction The proposed Avalon Golf Course site is roughly in the shape of a parallelogram under extensive sugarcane ( Saccharum sp. ) plantation with six feeders (5 named and one unnamed) and two rivers flowing South- easterly along its longer sides. Feeder Cresson and Feeder Edmond flow almost along two thirds of the site before joining to form Riviere Gros Ruisseau. Feeder Augustin which starts half way in the East of the site flows South –easterly to join Riviere Gros Ruisseau just before the latter flows outside the site at its South eastern boundary with St Aubin Sugar Estate. Two tributaries, Feeder Rivet and an unnamed Feeder flow along about a quarter of the site before joining to form Riviere Ruisseau Marron which winds down and out of the site with three to four loops flowing inside and out along the Eastern edge of the site. Feeder Enterrement starts in the middle of the last southern quarter of the site and flows more or less straight out of its eastern boundary with St Aubin Sugar Estate. The escarpments of the feeders and the Rivers vary from smooth slopes, steep slopes to almost vertical slopes and the vegetation consists predominantly of almost the same type of introduced species but with Ravenale ( Ravenala madacascariensis ) as the most dominant species, (see Fig. -

Lepidoptera of North America 5

Lepidoptera of North America 5. Contributions to the Knowledge of Southern West Virginia Lepidoptera Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University Lepidoptera of North America 5. Contributions to the Knowledge of Southern West Virginia Lepidoptera by Valerio Albu, 1411 E. Sweetbriar Drive Fresno, CA 93720 and Eric Metzler, 1241 Kildale Square North Columbus, OH 43229 April 30, 2004 Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University Cover illustration: Blueberry Sphinx (Paonias astylus (Drury)], an eastern endemic. Photo by Valeriu Albu. ISBN 1084-8819 This publication and others in the series may be ordered from the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity, Department of Bioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523 Abstract A list of 1531 species ofLepidoptera is presented, collected over 15 years (1988 to 2002), in eleven southern West Virginia counties. A variety of collecting methods was used, including netting, light attracting, light trapping and pheromone trapping. The specimens were identified by the currently available pictorial sources and determination keys. Many were also sent to specialists for confirmation or identification. The majority of the data was from Kanawha County, reflecting the area of more intensive sampling effort by the senior author. This imbalance of data between Kanawha County and other counties should even out with further sampling of the area. Key Words: Appalachian Mountains, -

Insect Survey of Four Longleaf Pine Preserves

A SURVEY OF THE MOTHS, BUTTERFLIES, AND GRASSHOPPERS OF FOUR NATURE CONSERVANCY PRESERVES IN SOUTHEASTERN NORTH CAROLINA Stephen P. Hall and Dale F. Schweitzer November 15, 1993 ABSTRACT Moths, butterflies, and grasshoppers were surveyed within four longleaf pine preserves owned by the North Carolina Nature Conservancy during the growing season of 1991 and 1992. Over 7,000 specimens (either collected or seen in the field) were identified, representing 512 different species and 28 families. Forty-one of these we consider to be distinctive of the two fire- maintained communities principally under investigation, the longleaf pine savannas and flatwoods. An additional 14 species we consider distinctive of the pocosins that occur in close association with the savannas and flatwoods. Twenty nine species appear to be rare enough to be included on the list of elements monitored by the North Carolina Natural Heritage Program (eight others in this category have been reported from one of these sites, the Green Swamp, but were not observed in this study). Two of the moths collected, Spartiniphaga carterae and Agrotis buchholzi, are currently candidates for federal listing as Threatened or Endangered species. Another species, Hemipachnobia s. subporphyrea, appears to be endemic to North Carolina and should also be considered for federal candidate status. With few exceptions, even the species that seem to be most closely associated with savannas and flatwoods show few direct defenses against fire, the primary force responsible for maintaining these communities. Instead, the majority of these insects probably survive within this region due to their ability to rapidly re-colonize recently burned areas from small, well-dispersed refugia. -

FL0107:Layout 1.Qxd

S. M. El Naggar & N. Sawady Pollen Morphology of Malvaceae and its taxonomic significance in Yemen Abstract El Naggar, S. M. & Sawady N.: Pollen Morphology of Malvaceae and its taxonomic signifi- cance in Yemen. — Fl. Medit. 18: 431-439. 2008. — ISSN 1120-4052. The pollen morphology of 20 species of Malvaceae growing in Yemen was investigated by light (LM) and scanning electron microscope (SEM). The studied taxa belong to 9 genera and three different tribes. These taxa are: Abelmoschus esculentus, Hibiscus trionum, H. micranthus, H. deflersii, H. palmatus, H. vitifolius, H. rosa-sinensis, H. ovalifolius, Gossypium hirsutum, Thespesia populnea (L.) Solander ex Correa and Senra incana (Cav.) DC. (Hibiscieae); Malva parviflora and Alcea rosea (Malveae); Abutilon fruticosum, A. figarianum, A. bidentatum, A. pannosum, Sida acuta, S. alba and S. ovata (Abutileae). Pollen shape, size, aperture, exine structure and sculpturing as well as the spine characters proved that they are of high taxonom- ic value. Pollen characters with some other morphological characters are discussed in the light of the recent classification of the family in Yemen. Key words: Malvaceae, Morphology, Yemen. Introduction Malvaceae Juss. (s. str.) is a large family of herbs, shrubs and trees; comprising about 110 genera and 2000 species. It is a globally distributed family with primary concentrations of genera in the tropical and subtropical regions (Hutchinson 1967; Fryxell 1975, 1988 & 1998; Heywood 1993; La Duke & Doeby 1995; Mabberley 1997). Due to the high economic value of many taxa of Malvaceae (Gossypium, Hibiscus, Abelmoschus and Malva), several studies of different perspective have been carried out, such as those are: Edlin (1935), Bates and Blanchard (1970), Krebs (1994a, 1994b), Ray (1995 & 1998), Hosni and Araffa (1999), El Naggar (1996, 2001 & 2004), Pefell & al. -

Conceptual Design Documentation

Appendix A: Conceptual Design Documentation APPENDIX A Conceptual Design Documentation June 2019 A-1 APPENDIX A: CONCEPTUAL DESIGN DOCUMENTATION The environmental analyses in the NEPA and CEQA documents for the proposed improvements at Oceano County Airport (the Airport) are based on conceptual designs prepared to provide a realistic basis for assessing their environmental consequences. 1. Widen runway from 50 to 60 feet 2. Widen Taxiways A, A-1, A-2, A-3, and A-4 from 20 to 25 feet 3. Relocate segmented circle and wind cone 4. Installation of taxiway edge lighting 5. Installation of hold position signage 6. Installation of a new electrical vault and connections 7. Installation of a pollution control facility (wash rack) CIVIL ENGINEERING CALCULATIONS The purpose of this conceptual design effort is to identify the amount of impervious surface, grading (cut and fill) and drainage implications of the projects identified above. The conceptual design calculations detailed in the following figures indicate that Projects 1 and 2, widening the runways and taxiways would increase the total amount of impervious surface on the Airport by 32,016 square feet, or 0.73 acres; a 6.6 percent increase in the Airport’s impervious surface area. Drainage patterns would remain the same as both the runway and taxiways would continue to sheet flow from their centerlines to the edge of pavement and then into open, grassed areas. The existing drainage system is able to accommodate the modest increase in stormwater runoff that would occur, particularly as soil conditions on the Airport are conducive to infiltration. Figure A-1 shows the locations of the seven projects incorporated in the Proposed Action. -

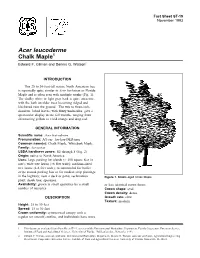

Acer Leucoderme Chalk Maple1 Edward F

Fact Sheet ST-19 November 1993 Acer leucoderme Chalk Maple1 Edward F. Gilman and Dennis G. Watson2 INTRODUCTION This 25 to 30-foot-tall native North American tree is reportedly quite similar to Acer barbatum or Florida Maple and is often seen with multiple trunks (Fig. 1). The chalky white or light gray bark is quite attractive, with the bark on older trees becoming ridged and blackened near the ground. The two to three-inch- diameter, lobed leaves, with fuzzy undersides, give a spectacular display in the fall months, ranging from shimmering yellow to vivid orange and deep red. GENERAL INFORMATION Scientific name: Acer leucoderme Pronunciation: AY-ser loo-koe-DER-mee Common name(s): Chalk Maple, Whitebark Maple Family: Aceraceae USDA hardiness zones: 5B through 8 (Fig. 2) Origin: native to North America Uses: large parking lot islands (> 200 square feet in size); wide tree lawns (>6 feet wide); medium-sized tree lawns (4-6 feet wide); recommended for buffer strips around parking lots or for median strip plantings in the highway; near a deck or patio; reclamation Figure 1. Middle-aged Chalk Maple. plant; shade tree; specimen Availability: grown in small quantities by a small or less identical crown forms number of nurseries Crown shape: oval Crown density: dense DESCRIPTION Growth rate: slow Texture: medium Height: 25 to 30 feet Spread: 15 to 30 feet Crown uniformity: symmetrical canopy with a regular (or smooth) outline, and individuals have more 1. This document is adapted from Fact Sheet ST-19, a series of the Environmental Horticulture Department, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. -

December 2012 Number 1

Calochortiana December 2012 Number 1 December 2012 Number 1 CONTENTS Proceedings of the Fifth South- western Rare and Endangered Plant Conference Calochortiana, a new publication of the Utah Native Plant Society . 3 The Fifth Southwestern Rare and En- dangered Plant Conference, Salt Lake City, Utah, March 2009 . 3 Abstracts of presentations and posters not submitted for the proceedings . 4 Southwestern cienegas: Rare habitats for endangered wetland plants. Robert Sivinski . 17 A new look at ranking plant rarity for conservation purposes, with an em- phasis on the flora of the American Southwest. John R. Spence . 25 The contribution of Cedar Breaks Na- tional Monument to the conservation of vascular plant diversity in Utah. Walter Fertig and Douglas N. Rey- nolds . 35 Studying the seed bank dynamics of rare plants. Susan Meyer . 46 East meets west: Rare desert Alliums in Arizona. John L. Anderson . 56 Calochortus nuttallii (Sego lily), Spatial patterns of endemic plant spe- state flower of Utah. By Kaye cies of the Colorado Plateau. Crystal Thorne. Krause . 63 Continued on page 2 Copyright 2012 Utah Native Plant Society. All Rights Reserved. Utah Native Plant Society Utah Native Plant Society, PO Box 520041, Salt Lake Copyright 2012 Utah Native Plant Society. All Rights City, Utah, 84152-0041. www.unps.org Reserved. Calochortiana is a publication of the Utah Native Plant Society, a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organi- Editor: Walter Fertig ([email protected]), zation dedicated to conserving and promoting steward- Editorial Committee: Walter Fertig, Mindy Wheeler, ship of our native plants. Leila Shultz, and Susan Meyer CONTENTS, continued Biogeography of rare plants of the Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge, Nevada. -

Inventory of Taxa for the Fitzgerald River National Park

Flora Survey of the Coastal Catchments and Ranges of the Fitzgerald River National Park 2013 Damien Rathbone Department of Environment and Conservation, South Coast Region, 120 Albany Hwy, Albany, 6330. USE OF THIS REPORT Information used in this report may be copied or reproduced for study, research or educational purposed, subject to inclusion of acknowledgement of the source. DISCLAIMER The author has made every effort to ensure the accuracy of the information used. However, the author and participating bodies take no responsibiliy for how this informrion is used subsequently by other and accepts no liability for a third parties use or reliance upon this report. CITATION Rathbone, DA. (2013) Flora Survey of the Coastal Catchments and Ranges of the Fitzgerald River National Park. Unpublished report. Department of Environment and Conservation, Western Australia. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to thank many people that provided valable assistance and input into the project. Sarah Barrett, Anita Barnett, Karen Rusten, Deon Utber, Sarah Comer, Charlotte Mueller, Jason Peters, Roger Cunningham, Chris Rathbone, Carol Ebbett and Janet Newell provided assisstance with fieldwork. Carol Wilkins, Rachel Meissner, Juliet Wege, Barbara Rye, Mike Hislop, Cate Tauss, Rob Davis, Greg Keighery, Nathan McQuoid and Marco Rossetto assissted with plant identification. Coralie Hortin, Karin Baker and many other members of the Albany Wildflower society helped with vouchering of plant specimens. 2 Contents Abstract .............................................................................................................................. -

Downtown Tree Management Plan City of Atlanta, Georgia November 2012

Downtown Tree Management Plan City of Atlanta, Georgia November 2012 Prepared for: City of Atlanta Department of Planning and Community Development Arborist Division, Tree Conservation Commission 55 Trinity Avenue SW, Suite 3800 Atlanta, Georgia 30303 Prepared by: Davey Resource Group A Division of The Davey Tree Expert Company 1500 North Mantua Street P.O. Box 5193 Kent, Ohio 44240 800-828-8312 Table of Contents Acknowledgments...................................................................................................................................................... iv Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................... vi Section 1: Urban Forest Overview.............................................................................................................................. 1 Section 2: Tree Inventory Assessment and Analysis ................................................................................................. 8 Overall Findings ........................................................................................................................................................ 11 Downtown Area Findings .......................................................................................................................................... 21 Expanded Inventory Area Findings ......................................................................................................................... -

Towards an Updated Checklist of the Libyan Flora

Towards an updated checklist of the Libyan flora Article Published Version Creative Commons: Attribution 3.0 (CC-BY) Open access Gawhari, A. M. H., Jury, S. L. and Culham, A. (2018) Towards an updated checklist of the Libyan flora. Phytotaxa, 338 (1). pp. 1-16. ISSN 1179-3155 doi: https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.338.1.1 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/76559/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Published version at: http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.338.1.1 Identification Number/DOI: https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.338.1.1 <https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.338.1.1> Publisher: Magnolia Press All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Phytotaxa 338 (1): 001–016 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/pt/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2018 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.338.1.1 Towards an updated checklist of the Libyan flora AHMED M. H. GAWHARI1, 2, STEPHEN L. JURY 2 & ALASTAIR CULHAM 2 1 Botany Department, Cyrenaica Herbarium, Faculty of Sciences, University of Benghazi, Benghazi, Libya E-mail: [email protected] 2 University of Reading Herbarium, The Harborne Building, School of Biological Sciences, University of Reading, Whiteknights, Read- ing, RG6 6AS, U.K. -

Survey of Lepidoptera of the Wainwright Dunes Ecological Reserve

SURVEY OF LEPIDOPTERA OF THE WAINWRIGHT DUNES ECOLOGICAL RESERVE Alberta Species at Risk Report No. 159 SURVEY OF LEPIDOPTERA OF THE WAINWRIGHT DUNES ECOLOGICAL RESERVE Doug Macaulay Alberta Species at Risk Report No.159 Project Partners: i ISBN 978-1-4601-3449-8 ISSN 1496-7146 Photo: Doug Macaulay of Pale Yellow Dune Moth ( Copablepharon grandis ) For copies of this report, visit our website at: http://www.aep.gov.ab.ca/fw/speciesatrisk/index.html This publication may be cited as: Macaulay, A. D. 2016. Survey of Lepidoptera of the Wainwright Dunes Ecological Reserve. Alberta Species at Risk Report No.159. Alberta Environment and Parks, Edmonton, AB. 31 pp. ii DISCLAIMER The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the policies of the Department or the Alberta Government. iii Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... vi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................... vi 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 STUDY AREA ............................................................................................................. 2 3.0 METHODS ................................................................................................................... 6 4.0 RESULTS .................................................................................................................... -

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- BIBLIOGRAPHY

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- BIBLIOGRAPHY BIBLIOGRAPHY Ackerfield, J., and J. Wen. 2002. A morphometric analysis of Hedera L. (the ivy genus, Araliaceae) and its taxonomic implications. Adansonia 24: 197-212. Adams, P. 1961. Observations on the Sagittaria subulata complex. Rhodora 63: 247-265. Adams, R.M. II, and W.J. Dress. 1982. Nodding Lilium species of eastern North America (Liliaceae). Baileya 21: 165-188. Adams, R.P. 1986. Geographic variation in Juniperus silicicola and J. virginiana of the Southeastern United States: multivariant analyses of morphology and terpenoids. Taxon 35: 31-75. ------. 1995. Revisionary study of Caribbean species of Juniperus (Cupressaceae). Phytologia 78: 134-150. ------, and T. Demeke. 1993. Systematic relationships in Juniperus based on random amplified polymorphic DNAs (RAPDs). Taxon 42: 553-571. Adams, W.P. 1957. A revision of the genus Ascyrum (Hypericaceae). Rhodora 59: 73-95. ------. 1962. Studies in the Guttiferae. I. A synopsis of Hypericum section Myriandra. Contr. Gray Herbarium Harv. 182: 1-51. ------, and N.K.B. Robson. 1961. A re-evaluation of the generic status of Ascyrum and Crookea (Guttiferae). Rhodora 63: 10-16. Adams, W.P. 1973. Clusiaceae of the southeastern United States. J. Elisha Mitchell Sci. Soc. 89: 62-71. Adler, L. 1999. Polygonum perfoliatum (mile-a-minute weed). Chinquapin 7: 4. Aedo, C., J.J. Aldasoro, and C. Navarro. 1998. Taxonomic revision of Geranium sections Batrachioidea and Divaricata (Geraniaceae). Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 85: 594-630. Affolter, J.M. 1985. A monograph of the genus Lilaeopsis (Umbelliferae). Systematic Bot. Monographs 6. Ahles, H.E., and A.E.