1939 Everyday Life Under Occupation: a Comparative Perspective Scenario

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sounds of War and Peace: Soundscapes of European Cities in 1945

10 This book vividly evokes for the reader the sound world of a number of Eu- Renata Tańczuk / Sławomir Wieczorek (eds.) ropean cities in the last year of the Second World War. It allows the reader to “hear” elements of the soundscapes of Amsterdam, Dortmund, Lwów/Lviv, Warsaw and Breslau/Wrocław that are bound up with the traumatising experi- ences of violence, threats and death. Exploiting to the full methodologies and research tools developed in the fields of sound and soundscape studies, the Sounds of War and Peace authors analyse their reflections on autobiographical texts and art. The studies demonstrate the role urban sounds played in the inhabitants’ forging a sense of 1945 Soundscapes of European Cities in 1945 identity as they adapted to new living conditions. The chapters also shed light on the ideological forces at work in the creation of urban sound space. Sounds of War and Peace. War Sounds of Soundscapes of European Cities in Volume 10 Eastern European Studies in Musicology Edited by Maciej Gołąb Renata Tańczuk is a professor of Cultural Studies at the University of Wrocław, Poland. Sławomir Wieczorek is a faculty member of the Institute of Musicology at the University of Wrocław, Poland. Renata Tańczuk / Sławomir Wieczorek (eds.) · Wieczorek / Sławomir Tańczuk Renata ISBN 978-3-631-75336-1 EESM 10_275336_Wieczorek_SG_A5HC globalL.indd 1 16.04.18 14:11 10 This book vividly evokes for the reader the sound world of a number of Eu- Renata Tańczuk / Sławomir Wieczorek (eds.) ropean cities in the last year of the Second World War. It allows the reader to “hear” elements of the soundscapes of Amsterdam, Dortmund, Lwów/Lviv, Warsaw and Breslau/Wrocław that are bound up with the traumatising experi- ences of violence, threats and death. -

On the Threshold of the Holocaust: Anti-Jewish Riots and Pogroms In

Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 11 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Szarota Tomasz On the Threshold of the Holocaust In the early months of the German occu- volume describes various characters On the Threshold pation during WWII, many of Europe’s and their stories, revealing some striking major cities witnessed anti-Jewish riots, similarities and telling differences, while anti-Semitic incidents, and even pogroms raising tantalising questions. of the Holocaust carried out by the local population. Who took part in these excesses, and what was their attitude towards the Germans? The Author Anti-Jewish Riots and Pogroms Were they guided or spontaneous? What Tomasz Szarota is Professor at the Insti- part did the Germans play in these events tute of History of the Polish Academy in Occupied Europe and how did they manipulate them for of Sciences and serves on the Advisory their own benefit? Delving into the source Board of the Museum of the Second Warsaw – Paris – The Hague – material for Warsaw, Paris, The Hague, World War in Gda´nsk. His special interest Amsterdam, Antwerp, and Kaunas, this comprises WWII, Nazi-occupied Poland, Amsterdam – Antwerp – Kaunas study is the first to take a comparative the resistance movement, and life in look at these questions. Looking closely Warsaw and other European cities under at events many would like to forget, the the German occupation. On the the Threshold of Holocaust ISBN 978-3-631-64048-7 GEP 11_264048_Szarota_AK_A5HC PLE edition new.indd 1 31.08.15 10:52 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 11 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Szarota Tomasz On the Threshold of the Holocaust In the early months of the German occu- volume describes various characters On the Threshold pation during WWII, many of Europe’s and their stories, revealing some striking major cities witnessed anti-Jewish riots, similarities and telling differences, while anti-Semitic incidents, and even pogroms raising tantalising questions. -

1945-1960 District Court in Warsaw RG-15.156M

Sąd Okręgowy w Warszawie (Sygn. SOW), 1945-1960 District Court in Warsaw RG-15.156M United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archive 100 Raoul Wallenberg Place SW Washington, DC 20024-2126 Tel. (202) 479-9717 Email: [email protected] Descriptive Summary Title: Sąd Okręgowy w Warszawie (Sygn. SOW) (District Court in Warsaw) Dates: 1945-1960 RG Number: RG-15.156M Accession Number: 2010.12 Creator: Poland. Sąd Okręgowy w Warszawie Extent: 21 microfilm reels (35 mm); 20,346 digital images (JPEG) Repository: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archive, 100 Raoul Wallenberg Place SW, Washington, DC 20024-2126 Languages: Polish, German, and Yiddish Administrative Information Restrictions on access: Researchers must complete and sign a User Declaration form before access is granted to materials from the Institute of National Remembrance (Instytut Pamięci Narodowej). Restrictions on reproduction and use: 1. Each researcher using the materials obtained from the Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) or materials whose originals belong to the IPN must complete the registration procedure required by USHMM. 2. Publication or reproduction of documents (in the original language, in facsimile form or in the form of a translation of an excerpt or of the entire document) or making them available to a 1 third party in any form requires the written consent of the Institute of National Remembrance. The use of an excerpt defined as the fair use right to quote does not require obtaining consent. 3. Researchers assume all responsibility for the use of materials that belong to the Institute of National Remembrance. 4. References to documents that belong to the Institute of National Remembrance must cite the Institute of National Remembrance as the owner of the original documents and include the full reference citation of the Institute of National Remembrance in the citations. -

DP Musée De La Libération UK.Indd

PRESS KIT LE MUSÉE DE LA LIBÉRATION DE PARIS MUSÉE DU GÉNÉRAL LECLERC MUSÉE JEAN MOULIN OPENING 25 AUGUST 2019 OPENING 25 AUGUST 2019 LE MUSÉE DE LA LIBÉRATION DE PARIS MUSÉE DU GÉNÉRAL LECLERC MUSÉE JEAN MOULIN The musée de la Libération de Paris – musée-Général Leclerc – musée Jean Moulin will be ofcially opened on 25 August 2019, marking the 75th anniversary of the Liberation of Paris. Entirely restored and newly laid out, the museum in the 14th arrondissement comprises the 18th-century Ledoux pavilions on Place Denfert-Rochereau and the adjacent 19th-century building. The aim is let the general public share three historic aspects of the Second World War: the heroic gures of Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque and Jean Moulin, and the liberation of the French capital. 2 Place Denfert-Rochereau, musée de la Libération de Paris – musée-Général Leclerc – musée Jean Moulin © Pierre Antoine CONTENTS INTRODUCTION page 04 EDITORIALS page 05 THE MUSEUM OF TOMORROW: THE CHALLENGES page 06 THE MUSEUM OF TOMORROW: THE CHALLENGES A NEW HISTORICAL PRESENTATION page 07 AN EXHIBITION IN STEPS page 08 JEAN MOULIN (¡¢¢¢£¤) page 11 PHILIPPE DE HAUTECLOCQUE (¢§¢£¨) page 12 SCENOGRAPHY: THE CHOICES page 13 ENHANCED COLLECTIONS page 15 3 DONATIONS page 16 A MUSEUM FOR ALL page 17 A HERITAGE SETTING FOR A NEW MUSEUM page 19 THE INFORMATION CENTRE page 22 THE EXPERT ADVISORY COMMITTEE page 23 PARTNER BODIES page 24 SCHEDULE AND FINANCING OF THE WORKS page 26 SPONSORS page 27 PROJECT PERSONNEL page 28 THE CITY OF PARIS MUSEUM NETWORK page 29 PRESS VISUALS page 30 LE MUSÉE DE LA LIBÉRATION DE PARIS MUSÉE DU GÉNÉRAL LECLERC MUSÉE JEAN MOULIN INTRODUCTION New presentation, new venue: the museums devoted to general Leclerc, the Liberation of Paris and Resistance leader Jean Moulin are leaving the Gare Montparnasse for the Ledoux pavilions on Place Denfert-Rochereau. -

Kopstukken Van De Nsb

KOPSTUKKEN VAN DE NSB Marcel Bergen & Irma Clement Marcel Bergen & Irma Clement KOPSTUKKEN VAN DE NSB UITGEVERIJ MOKUMBOOKS Inhoud Inleiding 4 Nationaalsocialisme en fascisme in Nederland 6 De NSB 11 Anton Mussert 15 Kees van Geelkerken 64 Meinoud Rost van Tonningen 98 Henk Feldmeijer 116 Max Blokzijl 132 Robert van Genechten 155 Johan Carp 175 Arie Zondervan 184 Tobie Goedewaagen 198 Henk Woudenberg 210 Evert Roskam 222 Noten 234 Literatuur 236 Colofon 238 dwang te overtuigen van de Groot-Germaanse gedachte. Het gevolg is dat Mussert zich met enkele getrouwen terug- trekt op het hoofdkwartier aan de Maliebaan in Utrecht en de toenemende druk probeert te pareren met notities, toespraken en concessies. Naarmate de bezetting voortduurt nemen de concessies die Mussert aan de Duitse bezetter doet toe. Inleiding De Nationaal Socialistische Beweging (NSB) speelt tijdens Het Rijkscommissariaat de Tweede Wereldoorlog een opmerkelijke rol. Op 14 mei 1940 aanvaardt Arthur Seyss-Inquart in de De NSB, die op 14 december 1931 in Utrecht is opgericht in Ridderzaal de functie van Rijkscommissaris voor de een zaaltje van de Christelijke Jongenmannen Vereeniging, bezette Nederlandse gebieden. Het Rijkscommissariaat vecht tijdens haar bestaan een richtingenstrijd uit. Een strijd is een civiel bestuursorgaan en bestaat verder uit: die gaat tussen de Groot-Nederlandse gedachte, die streeft – Friederich Wimmer (commissaris-generaal voor be- naar een onafhankelijk Groot Nederland binnen een Duits stuur en justitie en plaatsvervanger van Seyss-Inquart). Rijk en de Groot-Germaanse gedachte,waarin Nederland – Hans Fischböck (generaal-commissaris voor Financiën volledig opgaat in een Groot-Germaans Rijk. Niet alleen de en Economische Zaken). richtingenstrijd maakt de NSB politiek vleugellam. -

Diplomarbeit

DIPLOMARBEIT Organisationsstrukturen der deutschen Besatzungsverwaltungen in Frankreich, Belgien und den Niederlanden unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Stellung des SS- und Polizeiapparates vorgelegt von: Jörn Mazur am: 16. Dezember 1997 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. W. Seibel 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. E. Immergut UNIVERSITÄT KONSTANZ FAKULTÄT FÜR VERWALTUNGSWISSENSCHAFT Inhaltsverzeichnis Abkürzungsverzeichnis I. Einführung ............................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Thematik ................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Ziel ................................................................................................. 2 1.3 Fragestellungen und Thesen ....................................................................... 2 1.3.1 Fragestellungen ..................................................................................... 2 1.3.2 Thesen ..................................................................................... 3 1.4 Methodik ................................................................................................ 4 II. Stellung und Ausweitung des Machtbereichs des SS- und Polizeiapparates im Altreich ................................................................................................ 6 2.1 Stellung und Ausweitung des Machtbereichs des SS- und Polizeiapparates vor 1939 .................................................................................................... -

The Historical Journal VIA RASELLA, 1944

The Historical Journal http://journals.cambridge.org/HIS Additional services for The Historical Journal: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here VIA RASELLA, 1944: MEMORY, TRUTH, AND HISTORY JOHN FOOT The Historical Journal / Volume 43 / Issue 04 / December 2000, pp 1173 1181 DOI: null, Published online: 06 March 2001 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0018246X00001400 How to cite this article: JOHN FOOT (2000). VIA RASELLA, 1944: MEMORY, TRUTH, AND HISTORY. The Historical Journal, 43, pp 11731181 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/HIS, IP address: 144.82.107.39 on 26 Sep 2012 The Historical Journal, , (), pp. – Printed in the United Kingdom # Cambridge University Press REVIEW ARTICLE VIA RASELLA, 1944: MEMORY, TRUTH, AND HISTORY L’ordine eZ giaZ stato eseguito: Roma, le Fosse Ardeatine, la memoria. By Alessandro Portelli. Rome: Donzelli, . Pp. viij. ISBN ---.L... The battle of Valle Giulia: oral history and the art of dialogue. By A. Portelli. Wisconsin: Wisconsin: University Press, . Pp. xxj. ISBN ---.$.. [Inc.‘The massacre at Civitella Val di Chiana (Tuscany, June , ): Myth and politics, mourning and common sense’, in The Battle of Valle Giulia, by A. Portelli, pp. –.] Operazione Via Rasella: veritaZ e menzogna: i protagonisti raccontano. By Rosario Bentivegna (in collaboration with Cesare De Simone). Rome: Riuniti, . Pp. ISBN -- -.L... La memoria divisa. By Giovanni Contini. Milan: Rizzoli, . Pp. ISBN -- -.L... Anatomia di un massacro: controversia sopra una strage tedesca. By Paolo Pezzino. Bologna: Il Mulino, . Pp. ISBN ---.L... Processo Priebke: Le testimonianze, il memoriale. Edited by Cinzia Dal Maso. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Mensen, macht en mentaliteiten achter prikkeldraad: een historisch- sociologische studie van concentratiekamp Vught (1943-1944) Meeuwenoord, A.M.B. Publication date 2011 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Meeuwenoord, A. M. B. (2011). Mensen, macht en mentaliteiten achter prikkeldraad: een historisch-sociologische studie van concentratiekamp Vught (1943-1944). General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:04 Oct 2021 Mensen, macht en mentaliteiten achter prikkeldraad Een historisch-sociologische studie van concentratiekamp Vught (1943-1944) Marieke Meeuwenoord 1 Mensen, macht en mentaliteiten achter prikkeldraad 2 Mensen, macht en mentaliteiten achter prikkeldraad Een historisch-sociologische studie van concentratiekamp Vught (1943-1944) ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. -

International Achievements of Polish Urban Planning

ELABORATIONS INTERNATIONAL ACHIEVEMENTS OF POLISH URBAN PLANNING SAWOMIR GZELL MEASURES OF SUCCESS tecture, becomes an embarrassing and irresponsible composition of not-quite-new designs arranged of It is not easy to judge which examples of Polish toy bricks which should have been given to children, contemporary urban planning might possess the sta- though sampling in art and music fares quite well tus of works that achieved international success, and meanwhile. Bearing out the proposition on dyna- this includes creations in Poland as well as abroad. mism of assessment of urban designs is also the ac- One needs criteria for assessment, but intuition sug- ceptance of historicism, achieved some time ago and gests that even severe ones might be useless, while now well grounded, although the fashion for this is the selection of such criteria is not obvious. The num- too proceeding towards a decline. Another con [ rma- ber of citations, the frequency of publication of de- tion is the development of neomodernism in many scriptions and photographs, the number of imitators forms, even though critique of modernism itself and such like can of course be quanti [ ed, but against continues, with the effect i.a. that modernist archi- what should the resulting calculations be measured? tectural realizations are being physically removed; One would need to produce comparative tables but for instance the demolishing, ostensibly because of in spite of the work done, these would never bring frail condition, of department stores Supersam at about convincingly objective results. On the other Plac Unii Lubelskiej and Pawilon Chemii at Bracka hand, assessments transcending simple awarding of street in Warsaw, or the railway station in Katowice, points, such as admiration (or condemnation) of crit- or adding on buildings, or painting in bright colours ics, academic analyses, colleagues’ opinions, media even renowned housing estates constructed between reports etc, are obviously emburdened with the sin 1960-1980. -

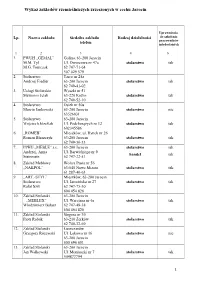

Wykaz Zakładów Rzemieślniczych Zrzeszonych W Cechu Jarocin

Wykaz zakładów rzemie ślniczych zrzeszonych w cechu Jarocin Uprawnienia Lp. Nazwa zakładu Siedziba zakładu Rodzaj działalno ści do szkolenia pracowników telefon młodocianych 1 2 3 4 6 1. PWUH „GEMAL” Golina, 63-200 Jarocin M.M. Tyl Ul. Dworcowa nr 47a stolarstwo tak M.G. Tomczak 62 747-71-64 507 029 579 2. Stolarstwo Tarce nr 25a Andrzej Fiedler 63-200 Jarocin stolarstwo tak 62 749-41-02 3. Usługi Stolarskie Wyszki nr 51 Sławomir Jelak 63-220 Kotlin stolarstwo tak 62 740-52-10 4. Stolarstwo Osiek nr 50a Marcin Jankowski 63-200 Jarocin stolarstwo nie 63526031 5. Stolarstwo 63-200 Jarocin Wojciech Józefiak Ul. Podchor ąż ych nr 12 stolarstwo tak 602345586 6. „ROMEB” Mieszków, ul. Rynek nr 26 Roman Błaszczyk 63-200 Jarocin stolarstwo tak 62 749-30-33 7. PPHU „MEBLE” s.c. 63-200 Jarocin stolarstwo tak Andrzej, Anna Ul. Barwickiego nr 9 handel tak Steinmetz 62 747-22-51 8. Zakład Meblowy Wolica Pusta nr 56 „NAKPOL” 63-040 Nowe Miasto stolarstwo tak 61 287-40-63 9. „ART.-STYL” Mieszków, 63-200 Jarocin Stolarstwo Ul. Jaroci ńska nr 27 stolarstwo tak Rafał Szik 62 747-75-50 604 454 826 10. Zakład Stolarski 63-200 Jarocin „MEBLEX” Ul. Warciana nr 6a stolarstwo tak Włodzimierz Bałasz 62 747-48-38 604 454 826 11. Zakład Stolarski St ęgosz nr 30 Piotr Robak 63-210 Żerków stolarstwo tak 62 740-32-69 12. Zakład Stolarski Łuszczanów Grzegorz Ró żewski Ul. Ł ąkowa nr 16 stolarstwo nie 63-200 Jarocin 600 696 651 13. Zakład Stolarski 63-200 Jarocin Jan Wałkowski Ul. -

Knut Døscher Master.Pdf (1.728Mb)

Knut Kristian Langva Døscher German Reprisals in Norway During the Second World War Master’s thesis in Historie Supervisor: Jonas Scherner Trondheim, May 2017 Norwegian University of Science and Technology Preface and acknowledgements The process for finding the topic I wanted to write about for my master's thesis was a long one. It began with narrowing down my wide field of interests to the Norwegian resistance movement. This was done through several discussions with professors at the historical institute of NTNU. Via further discussions with Frode Færøy, associate professor at The Norwegian Home Front Museum, I got it narrowed down to reprisals, and the cases and questions this thesis tackles. First, I would like to thank my supervisor, Jonas Scherner, for his guidance throughout the process of writing my thesis. I wish also to thank Frode Færøy, Ivar Kraglund and the other helpful people at the Norwegian Home Front Museum for their help in seeking out previous research and sources, and providing opportunity to discuss my findings. I would like to thank my mother, Gunvor, for her good help in reading through the thesis, helping me spot repetitions, and providing a helpful discussion partner. Thanks go also to my girlfriend, Sigrid, for being supportive during the entire process, and especially towards the end. I would also like to thank her for her help with form and syntax. I would like to thank Joachim Rønneberg, for helping me establish the source of some of the information regarding the aftermath of the heavy water raid. I also thank Berit Nøkleby for her help with making sense of some contradictory claims by various sources. -

Introduction

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. INTRODUCTION “We were taught as children”—I was told by a seventy- year-old Pole—“that we Poles never harmed anyone. A partial abandonment of this morally comfortable position is very, very difficult for me.” —Helga Hirsch, a German journalist, in Polityka, 24 February 2001 HE COMPLEX and often acrimonious debate about the charac- ter and significance of the massacre of the Jewish population of T the small Polish town of Jedwabne in the summer of 1941—a debate provoked by the publication of Jan Gross’s Sa˛siedzi: Historia za- głady z˙ydowskiego miasteczka (Sejny, 2000) and its English translation Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland (Princeton, 2001)—is part of a much wider argument about the totali- tarian experience of Europe in the twentieth century. This controversy reflects the growing preoccupation with the issue of collective memory, which Henri Rousso has characterized as a central “value” reflecting the spirit of our time.1 One key element in the understanding of collec- tive memory is the “dark past” of nations—those aspects of the na- tional past that provoke shame, guilt, and regret; this past needs to be integrated into the national collective identity, which itself is continu- ally being reformulated.2 In this sense, memory has to be understood as a public discourse that helps to build group identity and is inevita- bly entangled in a relationship of mutual dependence with other iden- tity-building processes.