A Finnic Holy Word and Its Subsequent History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kauppa-Alue 1 Akaa Hämeenkoski Kerava Länsi- Turunmaa Pirkkala

Kauppa-alue 1 Länsi- Akaa Hämeenkoski Kerava Turunmaa Pirkkala Siuntio Asikkala Hämeenkyrö Kiikoinen Marttila Pomarkku Somero Askola Hämeenlinna Kirkkonummi Masku Pori Sysmä Aura Iitti Kokemäki Miehikkälä Pornainen Säkylä Espoo Ikaalinen Koski Mynämäki Porvoo Taivassalo Eura Imatra Kotka Myrskylä Pukkila Tammela Eurajoki Inkoo Kouvola Mäntsälä Punkalaidun Tampere Forssa Janakkala Kuhmoinen Mäntyharju Pyhtää Tarvasjoki Hamina Jokioinen Kustavi Naantali Pyhäranta Turku Hanko Juupajoki Kärkölä Nakkila Pälkäne Tuusula Harjavalta Jämijärvi Köyliö Nastola Pöytyä Ulvila Hartola Jämsä 1) Lahti Nokia Raasepori Urjala Hattula Järvenpää Laitila Nousiainen Raisio Uusikaupunki Hausjärvi Kaarina Lapinjärvi Nummi-Pusula Rauma Valkeakoski Heinola Kangasala Lieto Nurmijärvi Riihimäki Vantaa Helsinki Kankaanpää Lohja Orimattila Rusko Vehmaa Hollola Karjalohja Loimaa Oripää Salo Vesilahti Huittinen Karkkila Loviisa Orivesi Sastamala Vihti Humppila Kauniainen Luumäki Padasjoki Sauvo Virolahti Hyvinkää Kemiönsaari Luvia Paimio Sipoo Ylöjärvi 2) 1) Lukuun ottamatta entisten Jämsänkosken ja Kuoreveden kuntien alueita, jotka kuuluvat kauppa-alueeseen 2 2) Lukuun ottamatta entisen Kurun kunnan aluetta, joka kuuluu kauppa-alueeseen 2 Kauppa-alue 2 Alajärvi Joutsa 7) Kesälahti 7) Lappajärvi Nilsiä 7) Pyhäjärvi Soini Vieremä 7) Alavieska Juankoski 7) Keuruu 7) Lapua Nivala Pyhäntä Sonkajärvi Vihanti Alavus Juva Kihniö Laukaa Närpiö Raahe Sulkava 7) Viitasaari Enonkoski 7) Jyväskylä 7) Kinnula Leppävirta 7) Oulainen Rantasalmi 7) Suomenniemi 7) Vimpeli Evijärvi Jämsä -

11:30 Fölin Runkoliikenneratkaisuja Ja Palvelupaketointia

Fölin palvelupaketointia ja runkoliikenneratkaisuja TURKU / KAARINA / RAISIO / LIETO / NAANTALI / RUSKO Sirpa Korte,www.foli.fi Föli Teatterilippuyhteistyö alkanut syyskuussa 2018: Teatterilippu TURKU / KAARINAon / RAISIO samalla / LIETO / FöliNAANTALI-lippu / RUSKO www.foli.fi ID-pohjainen maksujärjestelmä mahdollistaa tämän ja monta muuta palvelupakettia. TURKU / KAARINA / RAISIO / LIETO / NAANTALI / RUSKO www.foli.fi Höyrylaiva Ukko-Pekan ja Fölin yhteislippu TURKU / KAARINA / RAISIO / LIETO / NAANTALI / RUSKO www.foli.fi Lipun sai ostaa Fölin mobiilisovelluksesta TURKU / KAARINA / RAISIO / LIETO / NAANTALI / RUSKO www.foli.fi Lippukokeilu menossa VR:n kanssa TURKU / KAARINA / RAISIO / LIETO / NAANTALI / RUSKO www.foli.fi Mobiililiput kasvattavat suosiotaan TURKU / KAARINA / RAISIO / LIETO / NAANTALI / RUSKO www.foli.fi TURKU / KAARINAEMV -/ maksaminenRAISIO / LIETO / NAANTALI tulee / RUSKO Föliin vuonnawww.foli.fi 2019 TURKU / KAARINA / RAISIO / LIETO / NAANTALI / RUSKO www.foli.fi Haluamme olla mukana ihmisten arjessa. Se tarkoittaa helppokäyttöistä ja sujuvaa joukkoliikennettä, jolla pääsee tehokkaasti töihin, opiskelemaan, harrastuksiin. Mutta se tarkoittaa myös kivoja juttuja, kuten vesibussi Ruissalon luonnonkauniille saarelle tai bussiyhteys Kuhankuonon retkeilyreitistön luo. TURKU / KAARINA / RAISIO / LIETO / NAANTALI / RUSKO www.foli.fi Fölin palvelut laajenivat fölläreihin toukokuussa 2018. Kohta alkaa ensimmäinen fölläritalvi, föllärit ovat nimittäin käytössä ympäri vuoden. TURKU / KAARINA / RAISIO / LIETO / NAANTALI / RUSKO -

The Dispersal and Acclimatization of the Muskrat, Ondatra Zibethicus (L.), in Finland

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Wildlife Damage Management, Internet Center Other Publications in Wildlife Management for 1960 The dispersal and acclimatization of the muskrat, Ondatra zibethicus (L.), in Finland Atso Artimo Suomen Riistanhoito-Saatio (Finnish Game Foundation) Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdmother Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Artimo, Atso, "The dispersal and acclimatization of the muskrat, Ondatra zibethicus (L.), in Finland" (1960). Other Publications in Wildlife Management. 65. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdmother/65 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Wildlife Damage Management, Internet Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Other Publications in Wildlife Management by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. R I 1ST A TIE T L .~1 U ( K A I S U J A ,>""'liSt I " e'e 'I >~ ~··21' \. • ; I .. '. .' . .,~., . <)/ ." , ., Thedi$perscdQnd.a~C:li"'dti~otlin. of ,the , , :n~skret, Ond~trq ~ib.t~i~',{(.h in. Firtland , 8y: ATSO ARTIMO . RllSTATIETEELLISljX JULKAISUJA PAPERS ON GAME RESEARCH 21 The dispersal and acclimatization of the muskrat, Ondatra zibethicus (l.), in Finland By ATSO ARTIMO Helsinki 1960 SUOMEN FIN LANDS R I 1ST A N HOI T O-S A A T I b ] AK TV ARDSSTI FTELSE Riistantutkimuslaitos Viltforskningsinstitutet Helsinki, Unionink. 45 B Helsingfors, Unionsg. 45 B FINNISH GAME FOUNDATION Game Research Institute Helsinki, Unionink. 45 B Helsinki 1960 . K. F. Puromichen Kirjapaino O.-Y. The dispersal and acclimatization of the muskrat, Ondatra zibethicus (L.), in Finland By Atso Artimo CONTENTS I. -

PREPARING for the NEXT CHALLENGES PREPARING for the NEXT CHALLENGES EDIA FACTS Table of & FIGURES Contents 2015 / 2016 04

2015 / 2016 PREPARING FOR THE NEXT CHALLENGES PREPARING FOR THE NEXT CHALLENGES EDIA FACTS Table of & FIGURES Contents 2015 / 2016 04 A24 Grupp 08 Aburgus 09 Adrem Pärnu 10 Aktors 11 Alunaut 12 ASA Quality Services 13 BAE Systems Hägglunds 14 Baltic Armaments 15 Baltic Workboats 16 Baltic Defence & Technology 17 BLRT Grupp 18 Bristol Trust 19 Bytelife Solutions 20 CF&S Estonia 21 Combat Armoring Group 22 Cybernetica 23 Defendec 24 Ecometal 25 Eksamo 26 ELI 27 Empower 28 Englo 29 Eolane Tallinn 30 Eesti Energia 31 Fujitsu Estonia 32 G4S Eesti 33 Galvi-Linda 34 General Dynamics 35 Gevatex 36 Gladius Baltic 37 Harju Elekter 38 HK Nõustamise 39 EDIA FACTS Table of & FIGURES Contents 2015 / 2016 05 I.V.A. Leon 40 Icefire 41 Karla Auto O.K 42 Kitman Thulema 43 Kommivabrik 44 Kulinaaria 45 Maru 46 MBDA 47 Milectria 48 Milrem 49 Nefab Packaging 50 Norcar-BSB Eesti 51 Nordic Armoury 52 Profline 53 Rantelon 54 RRK 55 Samelin 56 Sangar 57 Sebe 58 Semetron 59 Silwi Autoehituse 60 Skeleton Technologies 61 Suva 62 Telegrupp 63 Televõrk 64 TerraMil 65 Threod Systems 66 Toci 67 Vequrity 68 Viking Security 69 YKK Finland 70 All members 71 Estonia – vibrant transformations in defence industry Defence innovation plays a vital role in Estonian economy. We are a member of EU and NATO since 2004 and our long experience in engineering and electronics industry serves as a good basis for defence and dual-use manufacturing. Today Estonia is well known also for its achievements in cyber security and cyber defence, both are Estonia’s trademarks in security and defence policy within NATO and the EU. -

Toimintakertomus 2019

MTK - Varsinais-Suomi 2019 TOIMINTAKERTOMUS Kannen kuva: Kuva-Plugi Julkaisun muut kuvat MTK-Varsinais-Suomen kuva-arkistosta, ellei muuta ole mainittu. Taitto: TM-suunnittelu Painopaikka: Sälekarin Kirjapaino Oy 2020 MTK - Varsinais-Suomi 2019 TOIMINTAKERTOMUS MTK-Varsinais-Suomi ry RAUMA Osoite: Hintsantie 3 21200 RAISIO Puhelin: 020 413 3580 Kotisivut: varsinais-suomi.mtk.fi Sähköposti: [email protected] VT 8 [email protected] KT 40 Löydät meidät myös Facebookista Kauppa- Kotisivut: varsinais-suomi.mtk.fi keskus Mylly Maaseudun Tulevaisuus -lehden ilmoituskonttori TURKU NAANTALI Kodisjoki Alastaro Metsämaa Laitila Oripää Kalanti - Uusikaupunki Yläne Loimaan seutu Karjala Mellilä Mynämäki Pöytyä Lokalahti Vehmaa Nousiainen Mietoinen Vahto Aura Koski Somero Kustavi Taivassalo Paattinen Tarvasjoki Masku Rusko Marttila Somerniemi Lieto Kuusjoki Raisio Meri-Naantali Paimio Turun seutu Kiikala Piikkiö Pertteli Salon seutu Rymättylä Kakskerta Suomusjärvi Sauvo - Karuna Angelniemi Parainen - Nauvo Kisko Perniö Särkisalo MTK-Varsinais-Suomen toimialue ja maataloustuottajain yhdistykset 2020. Yhdistyksiä 47, jäseniä 12270. 4 MTK Varsinais-Suomi | Toimintakertomus 2019 Toimihenkilöt ja yhteystiedot Varsinais-Suomen vuonna 2020 maataloustuottajain säätiö Toiminnanjohtaja Asiamies Paavo Myllymäki Ville Reunanen 020 413 3581 ja 040 5828261 040 5502908 [email protected] Aluepäällikkö Aino Launto-Tiuttu 020 413 3587 ja 040 5570736 Maa- ja metsätaloustuottajain keskusliitto Aluepäällikkö Terhi Löfstedt Osoite: Simonkatu 6, 00100 HELSINKI -

KUNTAJAON MUUTOKSET, JOISSA KUNTA on LAKANNUT 1.1.2021 Taulu I

KUNTAJAON MUUTOKSET, JOISSA KUNTA ON LAKANNUT 1.1.2021 Taulu I LAKANNUT KUNTA VASTAANOTTAVA KUNTA Kunnan nimi Kuntanumero Lakkaamispäivä Kunnan nimi Kuntanumero Huomautuksia Ahlainen 001 010172 Pori 609 Aitolahti 002 010166 Tampere 837 Akaa 003 010146 Kylmäkoski 310 ks. tämä taulu: Kylmäkoski-310 Sääksmäki 788 ks. tämä taulu: Sääksmäki-788 Toijala 864 ks. tämä taulu: Toijala-864 Viiala 928 ks. tämä taulu: Viiala-928 Alahärma 004 010109 Kauhava 233 ks. tämä taulu: Kortesjärvi-281 ja Ylihärmä-971 Alastaro 006 010109 Loimaa 430 ks. tämä taulu: Mellilä-482 Alatornio 007 010173 Tornio 851 Alaveteli 008 010169 Kruunupyy 288 Angelniemi 011 010167 Halikko 073 ks. tämä taulu: Halikko-073 Anjala 012 010175 Sippola 754 ks. taulu II: Sippola-754 Anjalankoski 754 010109 Kouvola 286 ks. tämä taulu: Elimäki-044, Jaala-163, Kuusankoski-306, Valkeala-909 Anttola 014 311200 Mikkeli 491 ks. tämä taulu: Mikkelin mlk-492 Artjärvi 015 010111 Orimattila 560 Askainen 017 010109 Masku 481 ks. tämä taulu: Lemu-419 Bergö 032 010173 Maalahti 475 Björköby 033 010173 Mustasaari 499 Bromarv 034 010177 Hanko 078 Tenhola 842 ks. tämä taulu: Tenhola-842 Degerby 039 010146 lnkoo 149 Dragsfjärd 040 010109 Kemiönsaari 322 ks. tämä taulu: Kemiö-243 ja Västanfjärd-923 Elimäki 044 010109 Kouvola 286 ks. tämä taulu: Jaala-163, Kuusankoski-306, Anjalankoski-754, Valkeala-909 Eno 045 010109 Joensuu 167 ks. tämä taulu: Pyhäselkä-632 Eräjärvi 048 010173 Orivesi 562 Haaga 068 010146 Helsinki 091 Haapasaari 070 010174 Kotka 285 Halikko 073 010109 Salo 734 ks. tämä taulu: Kiikala-252, Kisko-259, Kuusjoki-308, Muurla-501, Perniö-586, Pertteli-587, Suomusjärvi-776, Särkisalo-784 Hauho 083 010109 Hämeenlinna 109 ks. -

Väkiluku Kunnittain Ja Suuruus Järjestyksessä

Tilastokeskus S VT Väestö 1993:6 Statistikcentralen Befolkning Statistics Finland Population Väkiluku kunnittain ja suuruus järjestyksessä Befolkning kommunvis och i storleksordning 31. 12.1992 Nais- ja miesenemmistöiset kunnat Naista / 1 000 miestä 1 051-1 197 1 001-1 050 951-1 000 772 - 950 Tilastokeskus SVT Väestö 1993:6 Statistikcentralen Befolkning Statistics Finland Population Väkiluku kunnittain ja suuruus järjestyksessä Befolkning kommunvis och i storleksordning 31. 12.1992 Huhtikuu 1993 Julkaisun tiedot vapaasti lainattavissa. Lainattaessa mainittava lähteeksi Tilastokeskus. Helsinki - Helsingfors 1993 Tiedustelut - Förfrägningar: SVT Suomen Virallinen Tilasto Finlands Officiella Statistik Väestötilastotoimisto (90) 1734 3510 Official Statistics of Finland Helsinki 1993 3 Alkusanat Förord Tämä julkaisu sisältää kuntien väkiluvut lääneittäinDenna Publikation innehâller uppgifter om folkmäng- sekä kunnat väkiluvun mukaisessa suuruusjäijestyk-den i kommunema enligt Iän och folkmängden i kom- sessä. munema i storleksordning. Yksityiskohtaisempaa tietoa koko maan ja kuntienMera detaljerade uppgifter om befolkningensSam väestöstä on saatavilla syksyllä ilmestyvästä Väestörain ansättning i hela landet och i kommunema ingär i kenne 1992 julkaisusta. Publikationen Befolkningens sammansättning 1992 som utkommer pä hösten. Tämän julkaisun on toimittanut yliaktuaari LeenaPublikationen har rédigerais av överaktuarie Leena Kartovaara. Kartovaara. Aineisto Material Väestörekisterikeskus pitää yllä rekisteriä SuomenBefolkningsregistercentralen -

Toponyms and Place Heritage As Sources of Place Brand Value

Paula Sjöblom–Ulla Hakala Toponyms and place heritage as sources of place brand value 1. Introduction Commercial producers have long seen the advantage of branding their products, and the idea of discovering or creating uniqueness also attracts the leaders and governments of countries, states and cities (aShWorth 2009). However, traditional product marketing framework has proved to be inadequate for places; therefore, place branding has rather leaned on corporate branding. Place branding is a long-term, strategic process that requires continuity, and these actions take time to be recognised (KavaratZIS 2009). As generally recognised not only in onomastics but also in marketing, a name can be seen as the core of a brand. Therefore, a place name is the core of a place brand. Having a name is having an identity. A brand name has functions that can be regarded as sources of brand equity, and name changes have proved to cause discomfort and distress amongst consumers (e.g. RounD–RoPER 2012, BRoWn 2016). The name of a place – having stayed unchanged – has traditionally represented permanence and stability and could be regarded as the place’s memory (BASSO 1996, hEllElanD 2009). Referring to lauRa koSTanSki (2016) and her theory of toponymic attachment, place names carry strong emotional and functional attachments. This theory is very important also regarding place branding. According to GRAHAM et al. (2000), heritage can be defined as the past and future in the present. Accordingly, place heritage is heritage which is bound up with physical space that is a place. As for the concept of place, it is a named space (lÉVi-STRauSS 1962). -

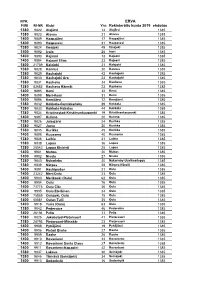

Kirje 09 Liite SRP

NYK. ERVA PIIRI RI-NR Klubi Yht: Rekisteröity kunta 2019 ehdotus 1380 9822 Alajärvi 14 Alajärvi 1385 1380 9823 Alavus 21 Alavus 1385 1400 9889 Haapajärvi 17 Haapajärvi 1385 1400 9890 Haapavesi 31 Haapavesi 1385 1380 9824 Ilmajoki 49 Ilmajoki 1385 1400 9892 Ivalo 28 Inari 1385 1400 9893 Kajaani 13 Kajaani 1385 1400 9894 Kajaani Elias 33 Kajaani 1385 1400 21739 Kalajoki 21 Kalajoki 1385 1380 9828 Kannus 30 Kannus 1385 1380 9829 Kauhajoki 42 Kauhajoki 1385 1380 9830 Kauhajoki Aro 24 Kauhajoki 1385 1380 9831 Kauhava 34 Kauhava 1385 1380 83683 Kauhava Härmät 23 Kauhava 1385 1400 9895 Kemi 32 Kemi 1385 1400 9899 Meri-Kemi 31 Kemi 1385 1400 9896 Kemijärvi 12 Kemijärvi 1385 1380 9832 Kokkola-Gamlakarleby 29 Kokkola 1385 1380 9833 Kokkola-Hakalax 44 Kokkola 1385 1380 9834 Kristinestad-Kristiinankaupunki 19 Kristiinankaupunki 1385 1400 9897 Kuhmo 20 Kuhmo 1385 1380 9826 Jalasjärvi 24 Kurikka 1385 1380 9827 Jurva 20 Kurikka 1385 1380 9835 Kurikka 45 Kurikka 1385 1400 9898 Kuusamo 40 Kuusamo 1385 1380 9836 Laihia 31 Laihia 1385 1380 9838 Lapua 36 Lapua 1385 1380 25542 Lapua Kiviristi 25 Lapua 1385 1400 9901 Muhos 20 Muhos 1385 1400 9902 Nivala 27 Nivala 1385 1380 9840 Nykarleby 40 Nykarleby-Uusikaarlepyy 1385 1380 9839 Närpes 28 Närpes-Närpiö 1385 1400 9891 Haukipudas 21 Oulu 1385 1400 23242 Meri-Oulu 23 Oulu 1385 1400 9900 Merikoski (Oulu) 62 Oulu 1385 1400 9904 Oulu 76 Oulu 1385 1400 73778 Oulu City 36 Oulu 1385 1400 9905 Oulu Eteläinen 34 Oulu 1385 1400 75859 Oulujoki, Oulu 15 Oulu 1385 1400 50881 Oulun Tulli 35 Oulu 1385 1400 9918 Tuira (Oulu) -

District 107 A.Pdf

Club Health Assessment for District 107 A through May 2016 Status Membership Reports LCIF Current YTD YTD YTD YTD Member Avg. length Months Yrs. Since Months Donations Member Members Members Net Net Count 12 of service Since Last President Vice No Since Last for current Club Club Charter Count Added Dropped Growth Growth% Months for dropped Last Officer Rotation President Active Activity Fiscal Number Name Date Ago members MMR *** Report Reported Email ** Report *** Year **** Number of times If below If net loss If no report When Number Notes the If no report on status quo 15 is greater in 3 more than of officers that in 12 within last members than 20% months one year repeat do not have months two years appears appears appears in appears in terms an active appears in in brackets in red in red red red indicated Email red Clubs less than two years old 125168 LIETO/ILMATAR 06/19/2015 Active 19 0 16 -16 -45.71% 0 0 0 0 Clubs more than two years old 119850 ÅBO/SKOLAN 06/27/2013 Active 20 1 2 -1 -4.76% 21 2 0 1 59671 ÅLAND/FREJA 06/03/1997 Active 31 2 4 -2 -6.06% 33 11 1 0 41195 ÅLAND/SÖDRA 04/14/1982 Active 30 2 1 1 3.45% 29 34 0 0 20334 AURA 11/07/1968 Active 38 2 1 1 2.70% 37 24 0 4 $536.59 98864 AURA/SISU 03/22/2007 Active 21 2 1 1 5.00% 22 3 0 0 50840 BRÄNDÖ-KUMLINGE 07/03/1990 Active 14 0 0 0 0.00% 14 0 0 32231 DRAGSFJÄRD 05/05/1976 Active 22 0 4 -4 -15.38% 26 15 0 13 20373 HALIKKO/RIKALA 11/06/1958 Active 31 1 1 0 0.00% 31 3 0 0 20339 KAARINA 02/21/1966 Active 39 1 1 0 0.00% 39 15 0 0 32233 KAARINA/CITY 05/05/1976 Active 25 0 5 -5 -16.67% -

Vene Vie – Satamaraportti Yhteenveto Vierasvenesatamien- Ja Laitureiden Kuntokartoituksesta Sekä Rakentamistarpeista

Vene vie –esiselvityksen kokonaisuuteen kuuluvat erillisinä julkaistut Vene vie - raportit: 1. Kyselytutkimus – Sähköisen kyselytutkimuksen yhteenveto 2. Kirjallisuuskatsaus – Katsaus muihin vesistömatkailun tutkimuksiin ja -raportteihin 3. Satamaraportti - Yhteenveto vierassatamien- ja laitureiden kuntokartoituksesta sekä rakentamistarpeista 4. Loppuraportti - Vene vie – esiselvitys Pirkanmaan vesistömatkailun ja vierasvenesatamien kehittämisestä Vene vie – satamaraportti Yhteenveto vierasvenesatamien- ja laitureiden kuntokartoituksesta sekä rakentamistarpeista. Arto Lammintaus Tampereen satamatoimisto, 2.10.2015 1 SISÄLLYS Johdanto ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Akaa, Toijala ................................................................................................................................................................................ 8 Hämeenkyrö, Kauhtua ............................................................................................................................................................. 9 Hämeenkyrö, Uskelanniemi ............................................................................................................................................... 10 Ikaalinen, Komppi ................................................................................................................................................................. -

39 DOUZELAGE CONFERENCE SIGULDA 24 April – 27 April 2014

AGROS (CY) ALTEA (E) ASIKKALA (FIN) th BAD KÖTZTING (D) 39 DOUZELAGE CONFERENCE BELLAGIO (I) BUNDORAN (IRL) CHOJNA (PL) GRANVILLE (F) HOLSTEBRO (DK) HOUFFALIZE (B) JUDENBURG (A) SIGULDA KÖSZEG (H) MARSASKALA (MT) MEERSSEN (NL) NIEDERANVEN (L) OXELÖSUND (S) th th PREVEZA (GR) 24 April – 27 April 2014 PRIENAI (LT) SESIMBRA (P) SHERBORNE (GB) SIGULDA (LV) SIRET (RO) SKOFIA LOKA (SI) MINUTES SUŠICE (CZ) TRYAVNA (BG) TÜRI (EST) ZVOLEN (SK) DOUZELAGE – EUROPEAN TOWN TWINNING ASSOCIATION PARTICIPANTS AGROS Andreas Latzias Metaxoula Kamana Alexis Koutsoventis Nicolas Christofi ASIKKALA Merja Palokangos-Viitanen Pirjo Ala-Hemmila Salomaa Miika BAD KOTZTING Wolfgang Kershcer Agathe Kerscher Isolde Emberger Elisabeth Anthofer Saskia Muller-Wessling Simona Gogeissl BELLAGIO Donatella Gandola Arianna Sancassani CHOJNA Janusz Cezary Salamończyk Norbert Oleskow Rafał Czubik Andrzej Będzak Anna Rydzewska Paweł Woźnicki BUNDORAN Denise Connolly Shane Smyth John Campbell GRANVILLE Fay Guerry Jean-Claude Guerry HOLSTEBRO Jette Hingebjerg Mette Grith Sorensen Lene Bisgaard Larsen Victoria Louise Tilsted Joachim Peter Tilsted 2 DOUZELAGE – EUROPEAN TOWN TWINNING ASSOCIATION HOUFFALIZE Alphonse Henrard Luc Nollomont Mathilde Close JUDENBURG Christian Fuller Franz Bachmann Andrea Kober Theresa Hofer Corinna Haasmann Marios Agathocleous KOSZEG Peter Rege Kitti Mercz Luca Nagy Aliz Pongracz MARSASKALA Mario Calleja Sandro Gatt Charlot Mifsud MEERSSEN Karel Majoor Annigje Luns-Kruytbosch Ellen Schiffeleers Simone Borm Bert Van Doorn Irene Raedts NIEDERANVEN Jos