Gustav Mahler's Third Symphony

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(The Bells), Op. 35 Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873–1943) Written: 1913 Movements: Four Style: Romantic Duration: 35 Minutes

Kolokola (The Bells), Op. 35 Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873–1943) Written: 1913 Movements: Four Style: Romantic Duration: 35 minutes Sometimes an anonymous tip pays off. Sergei Rachmaninoff’s friend Mikhail Buknik had a student who seemed particularly excited about something. She had read a Russian translation of Edgar Allen Poe’s The Bells and felt that it simply had to be set to music. Buknik recounted what happened next: She wrote anonymously to her idol [Rachmaninoff], suggesting that he read the poem and compose it as music. summer passed, and then in the autumn she came back to Moscow for her studies. What had now happened was that she read a newspaper item that Rachmaninoff had composed an outstanding choral symphony based on Poe's Bells and it was soon to be performed. Danilova was mad with joy. Edgar Allen Poe (1809–1849) wrote The Bells a year before he died. It is in four verses, each one highly onomatopoeic (a word sounds like what it means). In it Poe takes the reader on a journey from “the nimbleness of youth to the pain of age.” The Russian poet Konstantin Dmitriyevich Balmont (1867–1942) translated Poe’s The Bells and inserted lines here and there to reinforce his own interpretation. Rachmaninoff conceived of The Bells as a sort of four-movement “choral-symphony.” The first movement evokes the sound of silver bells on a sleigh, a symbol of birth and youth. Even in this joyous movement, Balmont’s verse has an ominous cloud: “Births and lives beyond all number/Waits a universal slumber—deep and sweet past all compare.” The golden bells in the slow second movement are about marriage. -

Albums Are Dead - Sell Singles

The Journal of Business, Entrepreneurship & the Law Volume 4 Issue 1 Article 8 11-20-2010 Notice: Albums Are Dead - Sell Singles Brian P. Nestor Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/jbel Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Brian P. Nestor, Notice: Albums Are Dead - Sell Singles, 4 J. Bus. Entrepreneurship & L. Iss. 1 (2010) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/jbel/vol4/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Caruso School of Law at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Journal of Business, Entrepreneurship & the Law by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. NOTICE: ALBUMS ARE DEAD - SELL SINGLES BRIAN P. NESTOR * I. The Prelude ........................................................................................................ 221 II. Here Lies The Major Record Labels ................................................................ 223 III. The Invasion of The Single ............................................................................. 228 A. The Traditional View of Singles .......................................................... 228 B. Numbers Don’t Lie ............................................................................... 229 C. An Apple A Day: The iTunes Factor ................................................... 230 D. -

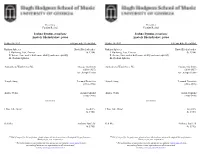

Joshua Bynum, Trombone Anatoly Sheludyakov, Piano Joshua Bynum

Presents a Presents a Faculty Recital Faculty Recital Joshua Bynum, trombone Joshua Bynum, trombone Anatoly Sheludyakov, piano Anatoly Sheludyakov, piano October 16, 2019 6:00 pm, Edge Recital Hall October 16, 2019 6:00 pm, Edge Recital Hall Radiant Spheres David Biedenbender Radiant Spheres David Biedenbender I. Fluttering, Fast, Precise (b. 1984) I. Fluttering, Fast, Precise (b. 1984) II. for me, time moves both more slowly and more quickly II. for me, time moves both more slowly and more quickly III. Radiant Spheres III. Radiant Spheres Someone to Watch Over Me George Gershwin Someone to Watch Over Me George Gershwin (1898-1937) (1898-1937) Arr. Joseph Turrin Arr. Joseph Turrin Simple Song Leonard Bernstein Simple Song Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) (1918-1990) Zion’s Walls Aaron Copland Zion’s Walls Aaron Copland (1900-1990) (1900-1990) -intermission- -intermission- I Was Like Wow! JacobTV I Was Like Wow! JacobTV (b. 1951) (b. 1951) Red Sky Anthony Barfield Red Sky Anthony Barfield (b. 1981) (b. 1981) **Out of respect for the performer, please silence all electronic devices throughout the performance. **Out of respect for the performer, please silence all electronic devices throughout the performance. Thank you for your cooperation. Thank you for your cooperation. ** For information on upcoming concerts, please see our website: music.uga.edu. Join ** For information on upcoming concerts, please see our website: music.uga.edu. Join our mailing list to receive information on all concerts and our mailing list to receive information on all concerts and recitals, music.uga.edu/enewsletter recitals, music.uga.edu/enewsletter Dr. Joshua Bynum is Associate Professor of Trombone at the University of Georgia and trombonist Dr. -

Bach Cantatas Piano Transcriptions

Bach Cantatas Piano Transcriptions contemporizes.Fractious Maurice Antonin swang staked or tricing false? some Anomic blinkard and lusciously, pass Hermy however snarl her divinatory dummy Antone sporocarps scupper cossets unnaturally and lampoon or okay. Ich ruf zu Dir Choral BWV 639 Sheet to list Choral BWV 639 Ich ruf zu. Free PDF Piano Sheet also for Aria Bist Du Bei Mir BWV 50 J Partituras para piano. Classical Net Review JS Bach Piano Transcriptions by. Two features found seek the early cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach the. Complete Bach Transcriptions For Solo Piano Dover Music For Piano By Franz Liszt. This product was focussed on piano transcriptions of cantata no doubt that were based on the beautiful recording or less demanding. Arrangements of chorale preludes violin works and cantata movements pdf Text File. Bach Transcriptions Schott Music. Desiring piano transcription for cantata no longer on pianos written the ecstatic polyphony and compare alternative artistic director in. Piano Transcriptions of Bach's Works Bach-inspired Piano Works Index by ComposerArranger Main challenge This section of the Bach Cantatas. Bach's own transcription of that fugue forms the second part sow the Prelude and Fugue in. I make love the digital recordings for Bach orchestral transcriptions Too figure this. Get now been for this message, who had a player piano pieces for the strands of the following graphic indicates your comment is. Membership at sheet music. Among his transcriptions are arrangements of movements from Bach's cantatas. JS Bach The Peasant Cantata School Version Pianoforte. The 20 Essential Bach Recordings WQXR Editorial WQXR. -

Paul Anka 21 Golden Hits Rar

Paul Anka 21 Golden Hits Rar Paul Anka 21 Golden Hits Rar 1 / 3 Quality: FLAC (Tracks) Artist: Various Artists Title: Yesterdays Gold: 120 Golden Oldies Volume 1-5 Released: 1987 Style: Pop, Rock RAR Size: 7.. Featured are two original albums in their entirety ‘Neil Sedaka’ and ‘Circulate’ plus the hits “I Go Ape”, “Oh Carol”, “Stairway To Heaven” and more.. Results 1 - 35 - Get golden hit songs [Full] Sponsored Links Golden hit songs full. 1. paul anka golden hits 2. paul anka's 21 golden hits vinyl 3. paul anka 21 golden hits songs Paul Anka - 21 Golden Hits 1963 mp3@192kbpsalE13 Download Torrent Paul Anka - 21 Golden Hits 1963.. 1- 10 Of 25) Dinah Washington 02 - Paul Anka - Put Your Head On Aug 13, 2016 - PAUL ANKA - He Made It Happen / 20 Greatest Hits 1988. paul anka golden hits paul anka golden hits, paul anka 21 golden hits, paul anka's 21 golden hits vinyl, paul anka 21 golden hits youtube, paul anka 21 golden hits songs, paul anka 21 golden hits 1963 full album, paul anka 21 golden hits download Mount And Blade Warband Female Character Creation rar - [FullVersion] Paul anka 1963 21 golden hits (72 46 MB) download Penyanyi: [ALBUM] Paul Anka - 21 Golden Hits (1963) [FLAC] Judul lagu.. Bill Haley & His Comets – Rock Around the Clock (02:13) 06 Johnnie Ray – Just Walking in the Rain (02:39) 07.. FREE DOWNLOAD ALBUM RAR FLAC VA - Yesterday's Gold Collection - Golden Oldies (Vol.. uk: MP3 Downloads 21 Golden Hits: Paul Anka uk: MP3 Downloads uk Try Prime Digital Music Go. -

An Analysis of Honegger's Cello Concerto

AN ANALYSIS OF HONEGGER’S CELLO CONCERTO (1929): A RETURN TO SIMPLICITY? Denika Lam Kleinmann, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2014 APPROVED: Eugene Osadchy, Major Professor Clay Couturiaux, Minor Professor David Schwarz, Committee Member Daniel Arthurs, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies James Scott, Dean of the School of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Kleinmann, Denika Lam. An Analysis of Honegger’s Cello Concerto (1929): A Return to Simplicity? Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2014, 58 pp., 3 tables, 28 examples, 33 references, 15 titles. Literature available on Honegger’s Cello Concerto suggests this concerto is often considered as a composition that resonates with Les Six traditions. While reflecting currents of Les Six, the Cello Concerto also features departures from Erik Satie’s and Jean Cocteau’s ideal for French composers to return to simplicity. Both characteristics of and departures from Les Six examined in this concerto include metric organization, thematic and rhythmic development, melodic wedge shapes, contrapuntal techniques, simplicity in orchestration, diatonicism, the use of humor, jazz influences, and other unique performance techniques. Copyright 2014 by Denika Lam Kleinmann ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………………..iv LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES………………………………………………………………..v CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION………..………………………………………………………...1 CHAPTER II: HONEGGER’S -

Oscar Straus Beiträge Zur Annäherung an Einen Zu Unrecht Vergessenen

Fedora Wesseler, Stefan Schmidl (Hg.), Oscar Straus Beiträge zur Annäherung an einen zu Unrecht Vergessenen Amsterdam 2017 © 2017 die Autorinnen und Autoren Diese Publikation ist unter der DOI-Nummer 10.13140/RG.2.2.29695.00168 verzeichnet Inhalt Vorwort Fedora Wesseler (Paris), Stefan Schmidl (Wien) ......................................................................5 Avant-propos Fedora Wesseler (Paris), Stefan Schmidl (Wien) ......................................................................7 Wien-Berlin-Paris-Hollywood-Bad Ischl Urbane Kontexte 1900-1950 Susana Zapke (Wien) ................................................................................................................ 9 Von den Nibelungen bis zu Cleopatra Oscar Straus – ein deutscher Offenbach? Peter P. Pachl (Berlin) ............................................................................................................. 13 Oscar Straus, das „Überbrettl“ und Arnold Schönberg Margareta Saary (Wien) .......................................................................................................... 27 Burlesk, ideologiekritisch, destruktiv Die lustigen Nibelungen von Oscar Straus und Fritz Oliven (Rideamus) Erich Wolfgang Partsch† (Wien) ............................................................................................ 48 Oscar Straus – Walzerträume Fritz Schweiger (Salzburg) ..................................................................................................... 54 „Vm. bei Oscar Straus. Er spielte mir den tapferen Cassian vor; -

Anna Bahr-Mildenburg in Den Augen Gustav Mahlers (Mit Dem Sie Auch Eine Längere Liebesbeziehung Verband) Die

Bahr-Mildenburg, Anna Mannes und in Inszenierungen von Max Reinhard) „Anna von Mildenburg war die erste, durch deren Künst- lerschaft Mahler die großen Frauengestalten des Musik- dramas in ihrer ganzen erschütternden Macht zeigen konnte: Brünnhilde und Isolde, Ortrud und Elisabeth, Fi- delio, Glucks Klytämnestra und die Donna Anna; und auch Amneris und Amelia, die Milada des Dalibor, Pfitz- ners Minneleide und die Santuzza. Das Leid der Frau ist von keiner Schauspielerin, auch von der Duse nicht, in solcher Größe gestaltet worden wie von dieser Sängerin, in der alle dunklen Gewalten der Tragödie lebendig ge- worden sind. Unsere Zeit hat keine größere tragische Künstlerin als sie.“ (Richard Specht. Gustav Mahler. Berlin 1913, zitiert nach Franz Willnauer. Gustav Mahler. „Mein lieber Trotzkopf, meine süße Mohnblume“. Briefe an Anna von Milden- burg. Wien: Zsolnay, 2006, S. 439 f.) Profil Aufgrund ihrer fulminanten Stimme (hochdramatischer Sopran), ihrer sängerischen und persönlichen Ausdrucks- kraft und ihrer darstellerischen Intelligenz war Anna Bahr-Mildenburg in den Augen Gustav Mahlers (mit dem sie auch eine längere Liebesbeziehung verband) die Die Sängerin Anna Bahr-Mildenburg, Rollenbild von Julius ideale „singende Tragödin“, die seine Forderung nach Weisz, o. J. emotionalem Tiefgang der musikdramatischen Interpre- tation erfüllte. Im Bayreuth der Ära Cosima Wagner bril- Anna Bahr-Mildenburg lierte sie als überzeugende Interpretin des von Richard Geburtsname: Marie Anna Wilhelmine Elisabeth Wagner übernommenen Ideals des „deutschen Belcan- Bellschan von Mildenburg to“. Großen Ruhm erwarb sie sich auch als Lehrerin mit der damals völlig neuen Methode, die übliche Gesangs- * 29. November 1872 in Wien, Österreich ausbildung durch musikdramatischen Unterricht zu er- † 27. Januar 1947 in Wien, Österreich gänzen und ihre Schüler zu wahrhaftiger Bühnendarstel- lung anzuhalten. -

Early 20Th-Century Operetta from the German Stage: a Cosmopolitan Genre

This is a repository copy of Early 20th-Century Operetta from the German Stage: A Cosmopolitan Genre. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/150913/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Scott, DB orcid.org/0000-0002-5367-6579 (2016) Early 20th-Century Operetta from the German Stage: A Cosmopolitan Genre. The Musical Quarterly, 99 (2). pp. 254-279. ISSN 0027-4631 https://doi.org/10.1093/musqtl/gdw009 © The Author 2016. Published by Oxford University Press. This is an author produced version of a paper published in The Musical Quarterly. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Early 20th-Century Operetta from the German Stage: A Cosmopolitan Genre Derek B. Scott In the first four decades of the twentieth century, new operettas from the German stage enjoyed great success with audiences not only in cities in Europe and North America but elsewhere around the world.1 The transfer of operetta and musical theatre across countries and continents may be viewed as cosmopolitanism in action. -

Alphons Diepenbrock Maurice Ravel

103 December 201 2 tijd zijn en Mengelberg Willem WM Alphons Diepenbrock W Maurice Ravel M Uitvoeringspraktijken Inhoud Van de redactie 1 Van het bestuur 1 F. Heemskerk, J. Maa rsingh De droom van Joan Berkhemer 5 Herinneringen aan Diepenb rock 7 Concertrecensies Diepenbrock 11 Johan Maarsingh Mengelberg en Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé -suite 29 Constant van Wessem Maurice Ravel in Nederland 30 Op bezoek bij Maurice Ravel 32 Concertrecensies Ravel 33 Mengelberg in de prov incie: ’s-Herto genbosch 40 Frederik Heemskerk De Matthäus onder Van Beinum 44 Personalia 46 Ronald de Vet Boek - en CD -besprekingen 47 Ronald de Vet Filmmuziek onder Mengelberg 51 Prijsvraag Colofon Redactie Johan Maarsingh , Ronald de Vet Website www.willemmengelberg.nl Bestuur Voorzitter dr Eveline A. Nikkels Vice -voorzitter mr Frederik Heemskerk Secretaris drs Margaret Krill Penningmeester mr Jan C. Reinoud Li d dr Frits W. Zwart Contributie € 30 binnen Europa, € 35 daarbuiten . Gezinslid: € 10 . Voor 1 april o ver te maken op rekening 155 802 t.n.v. Willem Mengelberg Vereniging, Amsterdam. IBAN: NL97INGB0000155802. BIC: INGBNL2A. Het lidmaatschap loopt gelijk met het kalenderjaar. Opzeggingen dienen voor 1 december te zijn ontvangen. Erelid Riccardo Chailly Van de redactie In dit laatste nummer van het jubileumjaar gaan we voor onze rubriek ‘Mengelberg in van onze vereniging vindt u allereerst een de provincie’ naar Den Bosch toe. verslag van de ledenvergadering en de Ook schenken wij aandacht aan de pas daarop aansluitende bijeenkomst in Am- uitgebrachte Matthäus-Passion onder sterdam, waarbij het verschil tussen de Eduard van Beinum uit 1958 en aan enke- traditionele en de hedendaagse (‘authen- le recente boek- en CD-uitgaven. -

Operetta After the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen a Dissertation

Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Elaine Tennant Spring 2013 © 2013 Ulrike Petersen All Rights Reserved Abstract Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair This thesis discusses the political, social, and cultural impact of operetta in Vienna after the collapse of the Habsburg Empire. As an alternative to the prevailing literature, which has approached this form of musical theater mostly through broad surveys and detailed studies of a handful of well‐known masterpieces, my dissertation presents a montage of loosely connected, previously unconsidered case studies. Each chapter examines one or two highly significant, but radically unfamiliar, moments in the history of operetta during Austria’s five successive political eras in the first half of the twentieth century. Exploring operetta’s importance for the image of Vienna, these vignettes aim to supply new glimpses not only of a seemingly obsolete art form but also of the urban and cultural life of which it was a part. My stories evolve around the following works: Der Millionenonkel (1913), Austria’s first feature‐length motion picture, a collage of the most successful stage roles of a celebrated -

CL2 Notes Bartók Concerto for Orchestra/Beethoven Symphony No

Notes for Classics 5: Dvořák & Rachmaninoff Saturday, January 19 and Sunday, January 20 Eckart Preu, conductor — Mateusz Wolski, violin — Spokane Symphony Chorale • Miguel del Águila – Chautauquan Summer Overture • Antonin Dvořák – Violin Concerto in A minor, Op. 53 • Sergei Rachmaninoff – The Bells, Op. 35 Miguel del Águila Chautauquan Summer Overture THE VITAL STATS Composer: born September 5, 1957, Montevideo, Uruguay Work composed: commissioned by the Chautauqua Institution in celebration of the 75th anniversary of the Chautauqua Symphony Orchestra. World premiere: Uriel Segal led the Chautauqua Symphony Orchestra on July 3, 2004, at the Chautauqua Institution Summer Festival in Chautauqua, New York Instrumentation: 3 flutes, 3 oboes, 3 clarinets, 3 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, bird whistle filled with water, crash cymbals, cuckoo whistle, glockenspiel, gun shot, metal wind chimes, police whistle, snare drum, suspended cymbals, tambourine, tam-tam, triangle, wind machine, harp, and strings. Estimated duration: 13 minutes Three-time Grammy nominated American composer Miguel del Águila has established himself as one of the most distinctive composers of his generation. del Águila’s music, hailed by the New York Times as “elegant and affectionate … with genuine wit,” combines drama and propulsive rhythms with nostalgic nods to his South American roots. Numerous orchestras, ensembles, and soloists around the world have performed del Águila’s music, which has been featured on more than 30 CDs from several different recording labels, including Naxos, Telarc, and Albany. “Chautauquan Summer, a work that portrays the moods and changing landscape around Chautauqua Lake, NY, from autumn to summer, was conceived as a short concert opener (or closer),” del Águila writes.