The Respiratory System Part 4: Breathing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Structure and Function of Breathing

CHAPTERCONTENTS The structure-function continuum 1 Multiple Influences: biomechanical, biochemical and psychological 1 The structure and Homeostasis and heterostasis 2 OBJECTIVE AND METHODS 4 function of breathing NORMAL BREATHING 5 Respiratory benefits 5 Leon Chaitow The upper airway 5 Dinah Bradley Thenose 5 The oropharynx 13 The larynx 13 Pathological states affecting the airways 13 Normal posture and other structural THE STRUCTURE-FUNCTION considerations 14 Further structural considerations 15 CONTINUUM Kapandji's model 16 Nowhere in the body is the axiom of structure Structural features of breathing 16 governing function more apparent than in its Lung volumes and capacities 19 relation to respiration. This is also a region in Fascla and resplrstory function 20 which prolonged modifications of function - Thoracic spine and ribs 21 Discs 22 such as the inappropriate breathing pattern dis- Structural features of the ribs 22 played during hyperventilation - inevitably intercostal musculature 23 induce structural changes, for example involving Structural features of the sternum 23 Posterior thorax 23 accessory breathing muscles as well as the tho- Palpation landmarks 23 racic articulations. Ultimately, the self-perpetuat- NEURAL REGULATION OF BREATHING 24 ing cycle of functional change creating structural Chemical control of breathing 25 modification leading to reinforced dysfunctional Voluntary control of breathing 25 tendencies can become complete, from The autonomic nervous system 26 whichever direction dysfunction arrives, for Sympathetic division 27 Parasympathetic division 27 example: structural adaptations can prevent NANC system 28 normal breathing function, and abnormal breath- THE MUSCLES OF RESPIRATION 30 ing function ensures continued structural adap- Additional soft tissue influences and tational stresses leading to decompensation. -

Thoracic Outlet and Pectoralis Minor Syndromes

S EMINARS IN V ASCULAR S URGERY 27 (2014) 86– 117 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com www.elsevier.com/locate/semvascsurg Thoracic outlet and pectoralis minor syndromes n Richard J. Sanders, MD , and Stephen J. Annest, MD Presbyterian/St. Luke's Medical Center, 1719 Gilpin, Denver, CO 80218 article info abstract Compression of the neurovascular bundle to the upper extremity can occur above or below the clavicle; thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) is above the clavicle and pectoralis minor syndrome is below. More than 90% of cases involve the brachial plexus, 5% involve venous obstruction, and 1% are associate with arterial obstruction. The clinical presentation, including symptoms, physical examination, pathology, etiology, and treatment differences among neurogenic, venous, and arterial TOS syndromes. This review details the diagnostic testing required to differentiate among the associated conditions and recommends appropriate medical or surgical treatment for each compression syndrome. The long- term outcomes of patients with TOS and pectoralis minor syndrome also vary and depend on duration of symptoms before initiation of physical therapy and surgical intervention. Overall, it can be expected that 480% of patients with these compression syndromes can experience functional improvement of their upper extremity; higher for arterial and venous TOS than for neurogenic compression. & 2015 Published by Elsevier Inc. 1. Introduction compression giving rise to neurogenic TOS (NTOS) and/or neurogenic PMS (NPMS). Much less common is subclavian Compression of the neurovascular bundle of the upper and axillary vein obstruction giving rise to venous TOS (VTOS) extremity can occur above or below the clavicle. Above the or venous PMS (VPMS). -

Ch22: Actions of the Respiratory Muscles

CHAPTER 22 ACTIONS OF THE RESPIRATORY MUSCLES André de Troyer he so-called respiratory muscles are those muscles that caudally and ventrally from their costotransverse articula- Tprovide the motive power for the act of breathing. Thus, tions, such that their ventral ends and the costal cartilages although many of these muscles are involved in a variety of are more caudal than their dorsal parts (Figure 22-2B, C). activities, such as speech production, cough, vomiting, and When the ribs are displaced in the cranial direction, their trunk motion, their primary task is to displace the chest wall ventral ends move laterally and ventrally as well as cra- rhythmically to pump gas in and out of the lungs. The pres- nially, the cartilages rotate cranially around the chon- ent chapter, therefore, starts with a discussion of the basic drosternal junctions, and the sternum is displaced ventrally. mechanical structure of the chest wall in humans. Then, the Consequently, there is usually an increase in both the lateral action of each group of muscles is analyzed. For the sake of and the dorsoventral diameters of the rib cage (see Figure clarity, the functions of the diaphragm, the intercostal mus- 22-2B, C). Conversely, a displacement of the ribs in the cau- cles, the muscles of the neck, and the muscles of the abdom- dal direction is usually associated with a decrease in rib cage inal wall are analyzed sequentially. However, since all these diameters. As a corollary, the muscles that elevate the ribs as muscles normally work together in a coordinated manner, their primary action have an inspiratory effect on the rib the most critical aspects of their mechanical interactions are cage, whereas the muscles that lower the ribs have an expi- also emphasized. -

Respiratory Function of the Rib Cage Muscles

Copyright @ERS Journals Ltd 1993 Eur Respir J, 1993, 6, 722-728 European Respiratory Journal Printed In UK • all rights reserved ISSN 0903 • 1936 REVIEW Respiratory function of the rib cage muscles J.N. Han, G. Gayan-Ramirez, A. Dekhuijzen, M. Decramer Respiratory function of the rib cage muscles. J.N. Han, G. Gayan-Ramirez, R. Respiratory Muscle Research Unit, Labo Dekhuijzen, M. Decramer. ©ERS Journals Ltd 1993. ratory of Pneumology, Respiratory ABSTRACT: Elevation of the ribs and expansion of the rib cage result from the Division, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, co-ordinated action of the rib cage muscles. We wished to review the action and Belgium. interaction of the rib cage muscles during ventilation. Correspondence: M. Decramer The parasternal intercostal muscles appear to play a predominant role during Respiratory Division quiet breathing, both in humans and in anaesthetized dogs. In humans, the para University Hospital sternal intercostals act in concert with the scalene muscles to expand the upper rib Weligerveld 1 cage, and/or to prevent it from being drawn inward by the action of the diaphragm. B-3212 Pellenberg The external intercostal muscles are considered to be active mainly during inspira Leuven tion, and the internal intercostal muscles during expiration. Belgium The respiratory activity of the external intercostals is minimal during quiet breathing both in man and in dogs, but increases with increasing ventilation. In Keywords: Chest wall mechanics contractile properties spiratory activity in the external intercostals can be enhanced in anaesthetized ani rib cage muscles mals and humans by inspiratory mechanical loading and by col stimulation, rib displacement suggesting that the external intercostals may constitute a reserve system, that may be recruited when the desired expansion of the rib cage is increased. -

Thoracic Outlet Syndrome of Pectoralis Minor Etiology Mimicking Cardiac

0008-3194/2012/311–315/$2.00/©JCCA 2012 Thoracic outlet syndrome of pectoralis minor etiology mimicking cardiac symptoms on activity: a case report Gary Fitzgerald BSc(NUI), BSc(Hons)(Chiro), MSc(Chiro), ICSSD* Thoracic outlet syndrome is the result of compression Le syndrome de la traversée thoracobrachial est le or irritation of neurovascular bundles as they pass résultat de la compression ou de l’irritation d’un from the lower cervical spine into the arm, via the paquet vasculonerveux au cours de son trajet entre axilla. If the pectoralis minor muscle is involved the la colonne cervicale inférieure et le bras, en passant patient may present with chest pain, along with pain par l’aisselle. Si le muscle petit pectoral est sollicité, and paraesthesia into the arm. These symptoms are also le patient peut subir de la douleur à la poitrine ainsi commonly seen in patients with chest pain of a cardiac que de la douleur et de la paresthésie dans le bras. origin. In this case, a patient presents with a history of On voit souvent ces symptômes aussi chez des patients left sided chest pain with pain and paraesthesia into the souffrant de douleurs thoraciques d’origine cardiaque. left upper limb, which only occurs whilst running. The Dans de tels cas, le patient présente des antécédents de symptoms were reproduced on both digital pressure over douleurs thoraciques du côté gauche, accompagnées the pectoralis minor muscle and on provocative testing de douleur et de paresthésie dans le membre supérieur for thoracic outlet syndrome. The patient’s treatment gauche, qui survient uniquement pendant que le patient therefore focused on the pectoralis minor muscle, with court. -

Pectoral Region and Axilla Doctors Notes Notes/Extra Explanation Editing File Objectives

Color Code Important Pectoral Region and Axilla Doctors Notes Notes/Extra explanation Editing File Objectives By the end of the lecture the students should be able to : Identify and describe the muscles of the pectoral region. I. Pectoralis major. II. Pectoralis minor. III. Subclavius. IV. Serratus anterior. Describe and demonstrate the boundaries and contents of the axilla. Describe the formation of the brachial plexus and its branches. The movements of the upper limb Note: differentiate between the different regions Flexion & extension of Flexion & extension of Flexion & extension of wrist = hand elbow = forearm shoulder = arm = humerus I. Pectoralis Major Origin 2 heads Clavicular head: From Medial ½ of the front of the clavicle. Sternocostal head: From; Sternum. Upper 6 costal cartilages. Aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle. Insertion Lateral lip of bicipital groove (humerus)* Costal cartilage (hyaline Nerve Supply Medial & lateral pectoral nerves. cartilage that connects the ribs to the sternum) Action Adduction and medial rotation of the arm. Recall what we took in foundation: Only the clavicular head helps in flexion of arm Muscles are attached to bones / (shoulder). ligaments / cartilage by 1) tendons * 3 muscles are attached at the bicipital groove: 2) aponeurosis Latissimus dorsi, pectoral major, teres major 3) raphe Extra Extra picture for understanding II. Pectoralis Minor Origin From 3rd ,4th, & 5th ribs close to their costal cartilages. Insertion Coracoid process (scapula)* 3 Nerve Supply Medial pectoral nerve. 4 Action 1. Depression of the shoulder. 5 2. Draw the ribs upward and outwards during deep inspiration. *Don’t confuse the coracoid process on the scapula with the coronoid process on the ulna Extra III. -

On the Anatomy of Intercostal Spaces in Man and Certain Other Mammals1 by Prof

ON THE ANATOMY OF INTERCOSTAL SPACES IN MAN AND CERTAIN OTHER MAMMALS1 BY PROF. M. A. H. SIDDIQI, M.B., D.L.O., M.S., F.R.C.S. (ENG.) AND DR A. N. MULLICK, M.B., B.S. Anatomy Department, King George's Medical College, Lucknow (India) TIHE standard description of the anatomy of the intercostal space has been discussed by Stibbe in a paper recently published in this Journal(2,3). Prof. Walmsley in 1916(1) showed that the intercostal nerves do not lie in the plane between the internal and external intercostal muscles but deep to the internal intercostal, and that they are separated from the pleura by a deeper musculo-fascial plane consisting of subcostal, intercostal and transversus thoracis muscles from behind forwards. According to Davies, Gladstone and Stibbe (3) there are four musculo-fascial planes in each space and in each space the main nerve lies with a collateral nerve deep to the internal intercostal. As the above paper effected a change in the teaching of the anatomy of intercostal space, we carried out the following investigations on human as well as on certain other Mammalian intercostal spaces. DISSECTION OF HUMAN INTERCOSTAL SPACES Sixty thoraces of different ages were dissected. From some of them the intercostal spaces were cut out en bloc to facilitate dissection; in others the thoracic wall was dissected as a whole. In the case of the foetuses microscopic sections were made to locate the muscular planes and the nerves. The results of our dissection were as follows: I. Intercostal muscles (fig. -

Postural and Ventilatory Functions of Intercostal Muscles

ACTA NEUROBIOL. EXP. 1973, 33: 355-380 Lecture delivered at Symposium "Neural control of breathing" held in Warszawa, August 1971 POSTURAL AND VENTILATORY FUNCTIONS OF INTERCOSTAL MUSCLES B. DURON Laboratory of Neurophysiology, Faculty of Medicine, Amiens, France Abstract. During spontaneous breathing, the interchondral muscles present a pat- tern of activity similar to that of the diaphragm. The external intercostals and most of the internal intercostals generally show electrical discharges not related to ventilatory rhythm. Studies of the electrical responses of these muscles in experi- mental variations of their length show that the external and internal intercostak are readily activated by this category of reflexes while the diaphragm and the interchondrals are not. Bilateral multisegmental sections of spinal dorsal roots do not affect the respiratory activity of the diaphragm and of the interchondral muscles; on the contrary, all types of activity - spontaneous or reflex - disappear from the intercostals. Electrical stimulation of appropriate points in the bulbar pyramids in decerebrate cats can activate at the same time different intercostals and leg muscles without modifying the rhythmic inspiratory activity of the diaphragm and the interchondrals. In preparations with chronically implanted electrodes, the inter- costal muscles are chiefly involved in posture. These results fit very well with our histological findings which disclose a much greater density of muscle spindles in external intercostals than in the diaphragm or in the interchondral muscles. INTRODUCTION Our conception of the role played by the intercostal muscles has been dominated for a long time by the anatomical concept of the "thoracic cage" starting with the original mechanical explanation of Hamberger (1748) based on geometric considerations. -

Ventilatory Action of the Hypaxial Muscles of the Lizard Iguana Iguana: a Function of Slow Muscle

exp. Biol. 143, 435-457 (1989) 435 rinted in Great Britain © The Company of Biologists Limited 1989 VENTILATORY ACTION OF THE HYPAXIAL MUSCLES OF THE LIZARD IGUANA IGUANA: A FUNCTION OF SLOW MUSCLE BY DAVID R. CARRIER* Department of Biology, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA Accepted 30 January 1989 Summary Patterns of muscle activity during lung ventilation, patterns of innervation and some contractile properties were measured in the hypaxial muscles of green iguanas. Electromyography shows that only four hypaxial muscles are involved in breathing. Expiration is produced by two deep hypaxial muscles, the transversalis and the retrahentes costarum. Inspiration is produced by the external and internal intercostal muscles. Although the two intercostal muscles are the main agonists of inspiration, neither is involved in expiration. This conflicts with the widely held notion that the different fibre orientations of the two intercostal muscles determine their ventilatory action. Several observations indicate that ventilation is produced by slow (i.e. non- twitch) fibres of these four muscles. First, electromyographic (EMG) activity recorded from these muscles during ventilation has an unusually low range of frequencies (<100Hz). Such low-frequency signals have been suggested to be characteristic of muscle fibres that do not propagate action potentials (i.e. slow fibres). Second, during inspiration, EMG activity is restricted to the medial sides of the two intercostal muscles. Muscle fibres from this region have multiple motor endplates and exhibit tonic contraction when immersed in saline solutions of high potassium content. Like the intercostals, the transversalis and retrahentes costarum muscles also contain fibres with multiple motor endplates. -

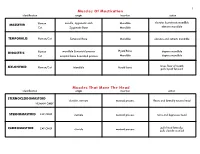

Muscles of Mastication Muscles That Move the Head

1 Muscles Of Mastication identification origin insertion action maxilla, zygomatic arch Mandible elevates & protracts mandible MASSETER Human Cat Zygomatic Bone Mandible elevates mandible TEMPORALIS Human/Cat Temporal Bone Mandible elevates and retracts mandible Hyoid Bone DIGASTRIC Human mandible & mastoid process depress mandible Cat occipital bone & mastoid process Mandible depress mandible raises floor of mouth; MYLOHYOID Human/Cat Mandible Hyoid bone pulls hyoid forward Muscles That Move The Head identification origin insertion action STERNOCLEIDOMAStoID clavicle, sternum mastoid process flexes and laterally rotates head HUMAN ONLY STERNOMAStoID CAT ONLY sternum mastoid process turns and depresses head pulls head laterally; CLEIDOMAStoID CAT ONLY clavicle mastoid process pulls clavicle craniad 2 Muscles Of The Hyoid, Larynx And Tongue identification origin insertion action Human Sternum Hyoid depresses hyoid bone STERNOHYOID Cat costal cartilage 1st rib Hyoid pulls hyoid caudally; raises ribs and sternum sternum Throid cartilage of larynx Human depresses thyroid cartilage STERNothYROID Cat costal cartilage 1st rib Throid cartilage of larynx pulls larynx caudad elevates thyroid cartilage and Human thyroid cartilage of larynx Hyoid THYROHYOID depresses hyoid bone Cat thyroid cartilage of larynx Hyoid raises larynx GENIOHYOID Human/Cat Mandible Hyoid pulls hyoid craniad 3 Muscles That Attach Pectoral Appendages To Vertebral Column identification origin insertion action Human Occipital bone; Thoracic and Cervical raises clavicle; adducts, -

Congenital Absence of the Pectoral Muscles

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.12.68.123 on 1 April 1937. Downloaded from CONGENITAL ABSENCE OF THE PECTORAL MUSCLES BY E. D. IRVINE, M.D., AND J. B. TILLEY, M.D. (Blackburn). The four patients described in this paper exhibit congenital absence of the pectoral muscles in varying degree, and illustrate many points of interest. Three of them were observed during routine and special medical examinations of approximately 15,000 elementary school children, and one was a pre-school child in hospital: it is interesting to note that Scheslinger, according to Rector', discovered five cases in 54,000 patients. Case 1 was discovered during the examination of a boy aged ten, the second of four children, who complained of cough: he is under observation http://adc.bmj.com/ on September 30, 2021 by guest. Protected copyright. FIG. 1. as a tuberculosis contact. The sterno-costal portion of the left pectoralis major and the left pectoralis minor are both missing. Although not previously noted, this is believed to be a congenital defect. The clavicular head of the pectoralis major is well developed and arises from the inner half of the clavicle; the deltoid is not hypertrophied (fig. 1). When the arms are extended above the head, a well-marked fold of skin running vertically across the axilla to the second left rib and interspace can be seen and in Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.12.68.123 on 1 April 1937. Downloaded from I 2d4 AIICIlIVES 0O' DISEASE IN CHILDHOOD the fold fibrous tissue can be felt deep to the skin: whether this is simply fascia or a vestigial or degenerated muscle is not known. -

The Anatomy and Function of the Equine Thoracolumbar Longissimus Dorsi Muscle

Aus dem Veterinärwissenschaftlichen Department der Tierärztlichen Fakultät der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Lehrstuhl für Anatomie, Histologie und Embryologie Vorstand: Prof. Dr. Dr. Fred Sinowatz Arbeit angefertigt unter der Leitung von Dr. Renate Weller, PhD, MRCVS The Anatomy and Function of the equine thoracolumbar Longissimus dorsi muscle Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der tiermedizinischen Doktorwürde der Tierärztlichen Fakultät der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Vorgelegt von Christina Carla Annette von Scheven aus Düsseldorf München 2010 2 Gedruckt mit der Genehmigung der Tierärztlichen Fakultät der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Dekan: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Joachim Braun Berichterstatter: Priv.-Doz. Dr. Johann Maierl Korreferentin: Priv.-Doz. Dr. Bettina Wollanke Tag der Promotion: 24. Juli 2010 3 Für meine Familie 4 Table of Contents I. Introduction................................................................................................................ 8 II. Literature review...................................................................................................... 10 II.1 Macroscopic anatomy ............................................................................................. 10 II.1.1 Comparative evolution of the body axis ............................................................ 10 II.1.2 Axis of the equine body ..................................................................................... 12 II.1.2.1 Vertebral column of the horse....................................................................