Jordán González , Laura. 2014. The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music of Latin America (In English)

Music of Latin America (in English) Class Code MUSIC – UA 9155 Instructor Juan Raffo Details Email: [email protected] Cell/WhatsApp: +54 911 6292 0728 Office Hours: Faculty Room, Wed 5-6 PM Class Details Mon/Wed 3:30-5:00 PM Location: Room Astor Piazzolla Prerequisites None Class A journey through the different styles of Latin American Popular Music (LAPM), Description particularly those coming from Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay. Their roots, influences and characteristics. Their social and historical context. Their uniqueness and similarities. Emphasis in the rhythmic aspect of folk music as a foundation for dance and as a resource of cultural identity. Even though there is no musical prerequisite, the course is recommended for students with any kind and/or level of musical experience. The course explores both the traditional and the contemporary forms of LAPM. Extensive listening/analysis of recorded music and in-class performing of practical music examples will be primary features of the course. Throughout the semester, several guest musicians will be performing and/or giving clinic presentations to the class. A short reaction paper will be required after each clinic. These clinics might be scheduled in a different time slot or even day than the regular class meeting, provided that there is no time conflict with other courses for any of the students. Desired Outcomes ● Get in contact with the vast music culture of Latin America ● Have a hands-on approach to learn and understand music ● Be able to aurally recognize and identify Latin American music genres and styles Assessment 1. Attendance, class preparation and participation, reaction papers (online): Components 20 % 2. -

Dans La Cantata Popular Santa María De Iquique

06,2 I 2021 Archiv für Textmusikforschung Identité(s) et mémoire(s) dans la Cantata popular Santa María de Iquique Olga LOBO (Grenoble)11 Summary The Cantata popular de Santa María de Iquique is one of the most important musical compositions of Quilapayún. Composed by Luis Advis in 1969 it tells the story of the massacre of the Iquique mineworkers in 1907. This cantata popular has become not only one of the symbols of the protest songs from the Seventies but also an icon for the universal struggle against injustice. The aim of this article is to study its history and different meanings in order to show the way how poetry, lyrics and music come together to tell the identities and memories of the Chilean people until now, when we celebrate its 50th anniversary. La Cantata de Luis Advis, une composition hybride et populaire La Cantata, entre deux traditions Interprétée pour la première fois en 1970 par le groupe Quilapayún, La Cantata popular Santa María de Iquique (Cantata) est une composition de Luis Advis (Iquique, 1935 – Santiago du Chili, 2005). Musicien autodidacte, il suivra dans les années 1950, une fois arrivé à Santiago, une formation classique avec Gustavo Becerra ou Albert Spikin. Si la tradi- tion classique sera déterminante pour la suite de sa carrière, les rythmes latino-américains ne font leur apparition dans le spectre de ses intérêts musicaux qu’à partir des années soixante. Son intérêt pour cette culture populaire était cependant tout relatif. Évoquant la genèse de la Cantata (dans une lettre du 15 mars 1984, envoyée à Eduardo Carrasco) Advis affirmera qu’à cette période-là il était un musicien « muy poco conocedor de la realidad popular musical y artística de [su] país » (Advis 2007, 16). -

Violeta Parra: Figura Canónica De La Música Chilena Y Universal

EDITORIAL II Violeta Parra: figura canónica de la música chilena y universal En su figura se conjugan ciertos rasgos que se han establecido como característicos de la música chilena. Uno de ellos es la importancia que la familia ha tenido en la formación, quehacer y proyección de tantos músicos nacionales. Este fue el caso de Violeta Parra Sandoval (San Carlos, 4 de octubre, 1917-Santiago, 5 de febrero, 1967). En una entrevista realizada por Magdalena Vicuña Lyon y publicada en la Revista Musical Chilena, N° 60 (1958), Violeta recuerda a su padre Nicanor Parra Parra, profesor primario, como “el mejor folklorista de la región y lo invitaban mucho a las fiestas”. De su madre, Clarisa Sandoval Navarrete, evoca que “cantaba las más hermosas canciones campesinas mientras trabajaba frente a su máquina de coser, era costurera”. Entre sus hermanos figura el gran poeta Nicanor Parra y el recordado músico y hombre de teatro Roberto Parra. La obra creativa de Violeta se proyectó en sus hijos Isabel Parra (Santiago, 1939) y Ángel Parra (Valparaíso, 1943-París, 2017), además de su nieta Tita (Cristina) Parra (Santiago, 1956). De acuerdo con el musicólogo Juan Pablo González, fue la misma Violeta quien le enseñó a Tita sus primeras canciones, junto con la percusión y la guitarra, desde que Tita tenía cuatro años de edad. Resulta natural, por tanto, que Violeta iniciara en la década de 1950 una de- nodada y exhaustiva labor de recolección e investigación de la música campesina chilena de tradición oral. Se pueden mencionar, a modo de ejemplo, los registros que se conservan en el Archivo de Música Tradicional de la Facultad de Artes de la Universidad de Chile, porque figuran en algunos de ellos los diálogos que la misma Violeta sostuviera con las cantoras campesinas. -

Historical Background

Historical Background Lesson 3 The Historical Influences… How They Arrived in Argentina and Where the Dances’ Popularity is Concentrated Today The Chacarera History: WHAT INFLUENCES MADE THE CHACARERA WHAT IT IS TODAY? HOW DID THESE INFLUENCES MAKE THEIR WAY INTO ARGENTINA? The Chacarera was influenced by the pantomime dances (the Gallarda, the Canario, and the Zarabanda) that were performed in the theaters of Europe (Spain and France) in the 1500s and 1600s. Later, through the Spanish colonization of the Americas, the Chacarera spread from Peru into Argentina during the 1800s (19th century). As a result, the Chacarera was also influenced by the local Indian culture (indigenous people) of the area. Today, it is enjoyed by all social classes, in both rural and urban areas. It has spread throughout the entire country except in the region of Patagonia. Popularity is concentrated in which provinces? It is especially popular in Santiago del Estero, Tucuman, Salta, Jujuy, Catamarca, La Rioja and Cordoba. These provinces are located in the Northwest, Cuyo, and Pampas regions of Argentina. There are many variations of the dance that are influenced by each of the provinces (examples: The Santiaguena, The Tucumana, The Cordobesa) *variations do not change the essence of the dance The Gato History: WHAT INFLUENCES MADE THE GATO WHAT IT IS TODAY? HOW DID THESE INFLUENCES MAKE THEIR WAY INTO ARGENTINA? The Gato was danced in many Central and South American countries including Mexico, Peru, Chile, Uruguay, and Paraguay, however, it gained tremendous popularity in Argentina. The Gato has a very similar historical background as the other playfully mischievous dances (very similar to the Chacarera). -

PF Vol19 No01.Pdf (12.01Mb)

PRAIRIE FORUM Vol. 19, No.1 Spring 1994 CONTENTS ARTICLES Wintering, the Outsider Adult Male and the Ethnogenesis of the Western Plains Metis John E. Foster 1 The Origins of Winnipeg's Packinghouse Industry: Transitions from Trade to Manufacture Jim Silver 15 Adapting to the Frontier Environment: Mixed and Dryland Farming near PincherCreek, 1895-1914 Warren M. Elofson 31 "We Are Sitting at the Edge of a Volcano": Winnipeg During the On-to-ottawa Trek S.R. Hewitt 51 Decision Making in the Blakeney Years Paul Barker 65 The Western Canadian Quaternary Place System R. Keith Semple 81 REVIEW ESSAY Some Research on the Canadian Ranching Frontier Simon M. Evans 101 REVIEWS DAVIS, Linda W., Weed Seeds oftheGreat Plains: A Handbook forIdentification by Brenda Frick 111 YOUNG, Kay, Wild Seasons: Gathering andCooking Wild Plants oftheGreat Plains by Barbara Cox-Lloyd 113 BARENDREGT, R.W., WILSON,M.C. and JANKUNIS, F.]., eds., Palliser Triangle: A Region in Space andTime by Dave Sauchyn 115 GLASSFORD, Larry A., Reaction andReform: ThePolitics oftheConservative PartyUnder R.B.Bennett, 1927-1938 by Lorne Brown 117 INDEX 123 CONTRIBUTORS 127 PRAIRIEFORUM:Journal of the Canadian Plains Research Center Chief Editor: Alvin Finkel, History, Athabasca Editorial Board: I. Adam, English, Calgary J.W. Brennan, History, Regina P. Chorayshi, Sociology, Winnipeg S.Jackel, Canadian Studies, Alberta M. Kinnear, History, Manitoba W. Last, Earth Sciences, Winnipeg P. McCormack, Provincial Museum, Edmonton J.N. McCrorie, CPRC, Regina A. Mills, Political Science, Winnipeg F. Pannekoek, Alberta Culture and Multiculturalism, Edmonton D. Payment, Parks Canada, Winnipeg T. Robinson, Religious Studies, Lethbridge L. Vandervort, Law, Saskatchewan J. -

Premio Nacional De Artes Musicales 2012. Perfil De Su

Juan Pablo Izquierdo Fernández: Premio Nacional de Artes Musicales 2012. Perfil de su quehacer en Chile Juan Pablo Izquierdo-Fernández Winner of the 2012 National Art Prize in Music: a Profile of his Activity in Chile por Carmen Peña Fuenzalida Instituto de Música Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile [email protected] Esta comunicación presenta un perfil de la actividad desarrollada por Juan Pablo Izquierdo (1935) como director de orquesta en Chile. En el contexto de su permanencia en tres épocas –décadas del 60, 80 y a partir de 2008– se revisan selectivamente repertorios que le ha correspondido conducir y sus vínculos musicales con orquestas nacionales, especialmente la Orquesta Sinfónica de Chile, la Orquesta Filarmónica de Santiago y la Orquesta de Cámara de Chile, junto con recuperar comentarios de la crítica. Palabras clave: Juan Pablo Izquierdo, orquestas de cámara chilenas, directores de orquesta, Premio Nacional de Arte, Orquesta Sinfónica de Chile, Orquesta de Cámara de Chile, Orquesta Filarmónica de Santiago. This article presents a profile of the activity of Juan Pablo Izquierdo (1935) as an orchestral conductor in Chile considering three periods. The first two periods correspond with the decades of the l960’s and 1980’s whereas the third period starts in the year 2008. A sample of the musical repertoire that he has conducted in Chile is analyzed along with his musical ties with national orchestras, in particular the Orquesta Sinfónica de Chile, the Orquesta Filarmónica de Santiago and the Orquesta de Cámara de Chile. Published reviews of his concerts in Chile are considered as part of the analysis. -

Violeta Parra, Después De Vivir Un Siglo

En el documental Violeta más viva que nunca, el poeta Gonzalo Rojas llama a Violeta la estrella mayor de Chile, lo más grande, la síntesis perfecta. Esta elocuente descripción habla del sitial privilegiado que en la actualidad, por fin, ocupa Violeta Parra en nuestro país, después de muchos años injustos en los que su obra fue reconocida en el extranjero y prácticamente ignorada en Chile. Hoy, reconocemos a Violeta como la creadora que hizo de lo popular una expre- sión vanguardista, llena de potencia e identidad, pero también como un talento universal, singular y, quizás, irrepetible. Violeta fue una mujer que logró articular en su arte corrientes divergentes, obligándonos a tomar conciencia sobre la diversidad territorial y cultural del país que, además de valorar sus saberes originarios, emplea sus recursos para pavimentar un camino hacia la comprensión y valoración de lo otro. Para ello, tendió un puente entre lo campesino y lo urbano, asumiendo las antiguas tradi- ciones instaladas en el mundo campesino, pero también, haciendo fluir y trans- formando un patrimonio cultural en diálogo con una conciencia crítica. Además, construyó un puente con el futuro, con las generaciones posteriores a ella, y también las actuales, que reconocen en Violeta Parra el canto valiente e irreve- rente que los conecta con su palabra, sus composiciones y su música. Pero Violeta no se limitó a narrar costumbres y comunicar una filosofía, sino que también se preocupó de exponer, reflexionar y debatir sobre la situación política y social de la época que le tocó vivir, desarrollando una conciencia crítica, fruto de su profundo compromiso social. -

Las Cuecas Como Representaciones Estético-Políticas De Chilenidad En

Las cuecas como representaciones estético-políticas de chilenidad… / Revista Musical Chilena Las cuecas como representaciones estético-políticas de chilenidad en Santiago entre 1979 y 1989 The Cuecas as Aesthetic and Political Representation of Chilenidad in Santiago Between 1979 and 1989 por Araucaria Rojas Sotoconil Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Chile [email protected] El siguiente texto pretende dar cuenta de los lugares por los que se desplazaron las cuecas como repre- sentaciones estético-políticas de chilenidad durante el período de la dictadura militar, más específicamente en Santiago entre 1979 y 1989. Es desde allí donde se establece un derrotero autori- tario que, a través de múltiples mecanismos, dispone una fusión forzosa entre determinado “tipo” de hacer-cueca y las prolongaciones “cultural”-identitarias de las que el régimen se apropia. La cueca, en tanto dispositivo político de determinada oficialidad y las cuecas como formas particulares que se exce- den de sus ordenamientos son las que pretenden ser aquí visitadas: cueca sola, cuecas de barrios populares (también nombradas brava y chora), adicionada a cuecas decididamente militantes de la resistencia, se disponen como actos y realidades que pugnan y plurifican el acto de cuequear. Palabras clave: cueca, chilenidad, dictadura, clandestinidad. The following article has the purpose of analysing the various meanings of the cuecas as aesthetic and political representations of chilenidad during the period of the military dictatorship, more specifically in Santiago between 1979 and 1989. It was then that an authoritarian procedure was created which by means of multiple mechanisms imposed the mingling between a certain type of cueca making and the cultural identity of the cueca assumed by the military government as part of its communication policies. -

Bronx Princess

POV Community Engagement & Education Discussion GuiDe Sweetgrass A Film by Ilisa Barbash and Lucien Castaing-Taylor www.pbs.org/pov POV BFIALcMKMgARKOEuRNSd’ S ITNAFTOERMMEANTTISON Boston , 2011 Recordist’s Statement We began work on this film in the spring of 2001. We were living in colorado at the time, and we heard about a family of nor - wegian-American sheepherders in Montana who were among the last to trail their band of sheep long distances — about 150 miles each year, all of it on hoof — up to the mountains for summer pasture. i visited the Allestads that April during lambing, and i was so taken with the magnitude of their life — both its allure and its arduousness — that we ended up following them, their friends and their irish-American hired hands intensely over the following years. to the point that they felt like family. Sweetgrass is one of nine films to have emerged from the footage we have shot over the last decade, the only one intended principally for theatrical exhibition. As the films have been shaped through editing, they seem to have become as much about the sheep as about their herders. the humans and animals that populate the footage commingle and crisscross in ways that have taken us by surprise. Sweetgrass depicts the twilight of a defining chapter in the history of the American West, the dying world of Western herders — descendants of scandinavian and northern european homesteaders — as they struggle to make a living in an era increasingly inimical to their interests. set in Big sky country, in a landscape of remarkable scale and beauty, the film portrays a lifeworld colored by an intense propinquity between nature and culture — one that has been integral to the fabric of human existence throughout history, but which is almost unimaginable for the urban masses of today. -

The Chilean Miracle

Proefschrift DEF stramien 14-09-2005 09:35 Pagina 1 The Chilean miracle PATRIMONIALISM IN A MODERN FREE-MARKET DEMOCRACY Proefschrift DEF stramien 14-09-2005 09:35 Pagina 2 The Chilean miracle Promotor: PATRIMONIALISM IN A MODERN Prof. dr. P. Richards FREE-MARKET DEMOCRACY Hoogleraar Technologie en Agrarische Ontwikkeling Wageningen Universiteit Copromotor: Dr. C. Kay Associate Professor in Development Studies Institute of Social Studies, Den Haag LUCIAN PETER CHRISTOPH PEPPELENBOS Promotiecommissie: Prof. G. Mars Brunel University of London Proefschrift Prof. dr. S.W.F. Omta ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor Wageningen Universiteit op gezag van de rector magnificus van Wageningen Universiteit, Prof. dr. ir. J.D. van der Ploeg prof. dr. M. J. Kropff, Wageningen Universiteit in het openbaar te verdedigen op maandag 10 oktober 2005 Prof. dr. P. Silva des namiddags te vier uur in de Aula. Universiteit Leiden Dit onderzoek is uitgevoerd binnen de onderzoeksschool CERES Proefschrift DEF stramien 14-09-2005 09:35 Pagina 4 Preface The work that follows is an attempt to blend together cultural anthropology with managerial sciences in a study of Chilean agribusiness and political economy. It also blends together theory and practice, in a new account of Chilean institutional culture validated through real-life consultancy experiences. This venture required significant cooperation from various angles. I thank all persons in Chile who contributed to the fieldwork for this study. Special Peppelenbos, Lucian thanks go to local managers and technicians of “Tomatio” - a pseudonym for the firm The Chilean miracle. Patrimonialism that cooperated extensively and became key subject of this study. -

Program Notes

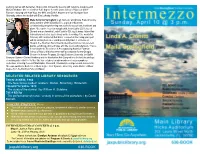

studying clarinet with her father, Nick Cionitti, followed by lessons with Valentine Anzalone and Michael Webster. She received her B.M. degree from the Crane School of Music at SUNY Potsdam, studying with Alan Woy. Her M.M. and D.M.A. degrees are from Michigan State University, where she studied with Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr. Maila Gutierrez Springfield is an instructor at Valdosta State University and a member of the Maharlika Trio, a group dedicated to commissioning and performing new works for saxophone, trombone and piano. She can be heard on saxophonist Joren Cain’s CD Voices of Dissent and on clarinetist Linda Cionitti’s CD Jag & Jersey. MusicWeb International selected Jag & Jersey as the recording of the month for February 2010 and noted that Maila “is superb in the taxing piano part with its striding bass lines and disjointed rhythms”. For Voices of Dissent, the American Record Guide describes Maila as “an excellent pianist, exhibiting solid technique and fine touch and pedal work." Twice- honored with the Excellence in Accompanying Award at Eastman School of Music, Maila has been staff accompanist for the Georgia Governor’s Honors Program, Georgia Southern University, the Buffet Crampon Summer Clarinet Academy and the Interlochen Arts Camp where she had the privilege of working with cellist Yo-Yo Ma. She has collaborated with members of major symphony orchestras, including those in Philadelphia, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Los Angeles and Jacksonville. She was awarded a Bachelor of Music degree from Syracuse University, and a Master of Music degree from the Eastman School of Music. SELECTED RELATED LIBRARY RESOURCES 780.92 A1N532, 1984 The New Grove modern masters : Bartók, Stravinsky, Hindemith 788.620712 S932s 1970 The study of the clarinet / by William H. -

Listado De Generos Autorizados.Xls

POR SUBGENERO LISTADO DE GENEROS AUTORIZADOS ACTUALIZADO AL 10 / 10 / 2006 SUBGENERO CODIGO GENERO AFRO 500 INTERNACIONAL AGOGO 594 INTERNACIONAL AIRES ESPAÑOLES 501 INTERNACIONAL ALBORADA 502 INTERNACIONAL ALEGRO VIVACE 455 SINFONICO Y CAMARA ANATEADA 627 FOLKLORE ANDANTE 400 SINFONICO Y CAMARA ARIA 401 SINFONICO Y CAMARA AUQUI AUQUI 633 FOLKLORE BAGUALA 300 FOLKLORE BAILECITO 301 FOLKLORE BAILE 402 INTERNACIONAL BAILES 302 FOLKLORE BAION 503 INTERNACIONAL BALADA 100 MELODICO BALLET 403 SINFONICO Y CAMARA BAMBUCO 595 INTERNACIONAL BARCAROLA 504 INTERNACIONAL BATUCADA 505 INTERNACIONAL BEAT 101 MELODICO BEGUINE 102 MELODICO BERCEUSE 404 SINFONICO Y CAMARA BLUES 103 MELODICO BOCETO 405 SINFONICO Y CAMARA BOGALOO 105 MELODICO BOLERO 104 MELODICO BOMBA 506 INTERNACIONAL BOOGIE BOOGIE 106 MELODICO BOSSA NOVA 507 INTERNACIONAL BOTECITO 508 INTERNACIONAL BULERIAS 509 INTERNACIONAL CACHACA 615 INTERNACIONAL CACHARPAYA 302 FOLKLORE CAJITA DE MUSICA 406 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CALIPSO 107 MELODICO CAMPERA 303 FOLKLORE CAN CAN 510 INTERNACIONAL CANCION 108 MELODICO CANCION DE CUNA 453 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANCION FOLKLORICA 358 FOLKLORE Página 1 POR SUBGENERO LISTADO DE GENEROS AUTORIZADOS ACTUALIZADO AL 10 / 10 / 2006 SUBGENERO CODIGO GENERO CANCION INDIA 643 FOLKLORE CANCION INFANTIL 407 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANCION MAPUCHE 642 FOLKLORE CANDOMBE 1 POPULAR CANON 408 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANTATA 409 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANTE JONDO 511 INTERNACIONAL CANZONETTA 109 MELODICO CAPRICCIO 410 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CARAMBA 304 FOLKLORE CARNAVAL 348 FOLKLORE CARNAVALITO