Full Page Fax Print

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Synarchism, Sinarquismo, Synarquismo, Sinarchismo, Synarchismo, Sinarchie, Synarchie, Sinarchia, Synarchía, Sinarq

On Synarchy (Synarchism, Sinarquismo, Synarquismo, Sinarchismo, Synarchismo, Sinarchie, Synarchie, Sinarchia, Synarchía, Sinarquia, Synarquia, Sinarkia, Synarkia; Global Synarchist Movement) Copyright © 2003 Joseph George Caldwell. All rights reserved. Posted at Internet website http://www.foundationwebsite.org. May be copied or reposted for non-commercial use, with attribution to author and website. (13 July 2003, updated 27 July 2003; title updated 15 April 2009) Contents On Synarchy (Synarchism, Sinarquismo, Synarquismo, Sinarchismo, Synarchismo, Sinarchie, Synarchie, Sinarchia, Synarchía, Sinarquia, Synarquia, Sinarkia, Synarkia; Global Synarchist Movement) .......................................................... 1 Origins of the Term Synarchy and Its Derivatives (synarchism, synarchic, synarchical, synarchist) .................. 1 Synarchist Concepts Since the Time of Saint-Yves ............ 26 Some Concluding Remarks ................................................ 32 Origins of the Term Synarchy and Its Derivatives (synarchism, synarchic, synarchical, synarchist) In my writings on a long-term-sustainable system of planetary management for Earth, I have variously used the terms “Platonic” and “synarchic” to describe the nature of the planetary management system. Neither of these terms is exactly “right” to describe the system that I am proposing. Plato wrote his Republic in the context of the Greek city- state of 500 BC, and Saint-Yves d’Alveydre developed his concept of Synarchy in the late 1800s. Since Saint-Yves’ concept is most closely aligned with what I propose for the management system of the planetary management organization, that is the term that I generally use. It should be recognized, however, that the terms synarchy and synarchism have been used by many different people over the years, and the particular concept that the user had in mind may differ from what I have proposed. -

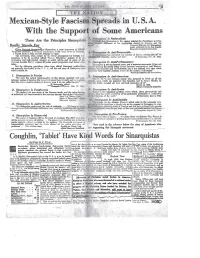

Mexican-Style Fascism Spreads in U. S. A. with the Support of Some Americans

PM, SUNDAY, MAY .21, 1944 THE NAT ION Mexican-Style Fascism Spreads in U. S. A. With the Support of Some Americans . 5. Smarquum Is Nationalistic These Are the Principles Sinarquismi "I submit that. Sinarquism is the a g selected by Providence to bring about Mexico's fulfilment of her appr to destby, America and the world." Preseneis littering del Sinorquinno, leaflet published by the Los Angeles or Sinarquism, a mass movement of 900,00 Sioarontst Regional Committee. mem rs is -we aces counterpart of the Neu Party in Germany, 6. Sinarquism Is Anti•Dernocratic e Fascist Party in IItaly and the Falange in Spain. "It [democracy has corrupted our concept of liberty, tutting.maa lais The movement, when judged by its official propaganda for foreign con- El Stnarquista, Nov. 27. 194L sumption, or by Its so-milled official 'Sixteen Principles," appears to be an relations with morality, justice and law." booffensive and high-minded attempt at social reform—just as many of the National Socialist Party's original 25 points sound progressive and decent even 7. Sinorquisth Is Anti.Parliamentary today. "Sinarquism Is not an electoral party, not a sectarian movement. It hos not But the following quotations, taken from official Sinarquist publications come to prolong the 'sordid bitter contest between 'conservatives' and 'liberals. not generally distributed in the U. S, A., tell the real stray of Sinarquism and between 'reactionaries' and 'revolutionists,' for it has realized with clear vision what it stands for. that from these horrible conflicts derive all the nation's nu.s• forhtnes." Prsoencis lit:laded del Sinorquiiisto. -

Religion and National Security: the Threat from Terrorist Cults

Click here for Full Issue of Fidelio Volume 13, Number 1-2, Spring-Summer 2004 What Ashcroft Would Prefer You Not To Know Religion and National Security: The Threat from Terrorist Cults The Synarchist threat from the presently continuing Martinist tradition of the French Revolution period’s Mesmer, Cagliostro,Joseph de Maistre, et al., is, once again, a leading issue of the current time. This was, originally, the banker- backed terrorist cult used to direct that great internal, systemic threat of 1789-1815 to France, and to the world of that time. This same banker-cult symbiosis was behind Mussolini’s dictatorship, behind Francisco Franco’s dictatorship, and behind Adolf Hitler’s role during 1923-45. This was the threat posed by prominent pro-Synarchists inside the British Establishment, who, during the World War II setting of Dunkirk, had attempted to bring Britain and France into that planned alliance with Hitler, Mussolini, Franco, and Japan—which would, if achieved, have aimed to destroy the U.S.A. itself by aid of that consort of global naval power. Synarchist history (counter-clockwise from top left): Spanish Inquisition, auto-da-fé, clipart.com. Spanish Inquisition, torture chamber. Grand Inquisitor Tómas de Torquemada, clipart.com. Count Joseph de Maistre. Fall of the Bastille, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress. Napoleon Bonaparte, www.arttoday.com. Viscount Castlereagh, dukesofbuckingham.org. Congress of Vienna, clipart.com. Friedrich Nietzsche, www.arttoday.com. Adolf Hitler and Hjalmar Schacht. H.G. Wells, www.arttoday.com. Bertrand Russell, Prints and Potographs Division, Library of Congress. Montagu Norman, www.arttoday.com. -

The Nazi-Instigated National Synarchist Union of Mexico: What It

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 31, Number 28, July 16, 2004 EIRSynarchy WHAT IT MEANS FOR TODAY The Nazi-Instigated National Synarchist Union ofMexico Part 2, by William F. Wertz, Jr. Part 1, which appeared in last week’s EIR, traced the origins D. Roosevelt had spoken in December 1932, and then again in of Synarchism in Mexico, including the founding of the Na- his Inaugural Address on March 1, 1933. The most important tional Synarchist Union (UNS) by the Nazis and the Spanish aspect of the agreement was that the United States officially Falangists, and its wartime role in support of the Axis cause. recognized Mexico’s sovereign ownership of its subsoil Here, a new chapter begins, after Pearl Harbor and the Mexi- wealth. The agreement contained six points: 1) an evaluation can declaration of war against the Axis powers: An anti- of the expropriated oil properties; 2) Mexico agreed to satisfy Roosevelt Anglo-American imperialist faction, acting all outstanding claims of U.S. citizens for revolutionary dam- through the Dulles-Buckley networks associated with Cardi- age and expropriated properties, through the payment of $40 nal Spellman and Bishop Fulton Sheen of the United States, million over 14 years; 3) negotiation of a reciprocal trade moved in to control the UNS. These networks remain active agreement; 4) the U.S. Treasury would stabilize currency to this day, including notably against the LaRouche forces in through the purchase of Mexican pesos, and would buy Mexi- Ibero-America. Two former LaRouche associates, Marivilia can silver at the fixed rate of 35¢ an ounce, renewing the Carrasco and Fernando Quijano, went over to the syn- arrangement it had prior to the oil expropriations; and 6) the archist camp. -

The Mexico Case: the Fascist Philosophy That Created Synarchism

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 30, Number 21, May 30, 2003 de Gaulle up to recently, opposed Synarchism, which is a sources as a leader of the so-called “Eurasians,” a group of strongly reactionary movement, financed by the Haute Russian emigre´s in the 1920s Berlin and Paris, led by Sir Banque. He has even ordered a confidential study to be made Samuel Hoare’s Guchkov and tied into the Soviet secret ser- on the subject, a copy of which has been seen by American vice project called “the Trust.” The “Eurasians” welcomed officers.” The report concluded, “If it is a fact that many indi- the Russian Revolution as a purgative force to wipe out cor- viduals who are holding positions of importance in the cabinet rupt Western civilization. Koje`ve’s own cosmology of great and the immediate entourage of General de Gaulle, are also tyrants counted Josef Stalin and Adolf Hitler as second only closely associated with political ideas alien to the program to Napoleon, in achieving the “end of history” goal of a true which de Gaulle and his government publicly endorse, then global tyranny. far-reaching political inferences may be drawn.” Of course, a decade later, leading wartime “Gaullist” Jacques Soustelle Strauss, Koje`ve, Schmitt, and Schacht would launch the Secret Army Organization (OAS), which While none of the American archive documents re- would be responsible for repeated assassination attempts viewed to date by EIR identify Nazi jurist Carl Schmitt as against de Gaulle, and would be implicated in the Permindex a Synarchist, circumstantial evidence points to that conclu- assassination of President John F. -

HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES Membei:S Have Answered to Their Names; Mr

1946 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUS~ 5209 Leslie Dean High And be not conformed to this 'world; The Clerk read the resolution, as fol I an Edward Holland but be ye transformed by the renewing lows: Archibald Barwell How 2d R ichard Bernard Humbert of your mind, that ye may prove what is R esolved, That the further expens~ s U.L J ames Patrick Hynes that good, and acceptable, and perfect, conducting the studies and investigation David Jenkins will of God. · authorized by House Resolution 5 of the pres Bruce Clifford Johnson ent Congress, incurred by the standing Com Robert Wayne Johnson Let us pray: Almighty God, unto whom mittee on Un-American Activities, acting as Frederick Steffe~ Kelsey all hearts are open, all desires known, a whole or by subcommittee, not to exceed William Joseph Kirkley and from whom no secrets are hid, $75,000, In addition to funds heretof.ore m ade R obert Charles Krulish available including expenditures for the Em cleanse the thoughts of our hearts by the ployment of experts, ::nd clerical, steno R obert Allison Lee inspiration of Thy holy will that we may Mich ael Bea uregard Lemly graphic, and other assistants, shall be paid R udolph Edwin Lenczyk perfectly love Thee and worthily magnify out of the contingent fund of the House on Glen n Milton Loboudger Thy holy name. Through Jesus Christ vouchers authorized by such committee, James Hect or MacDonald our Lord. Amen. signed by the chairman thereof, and ap- Charles Scott Marple .- proved by the Committee on Accounts. Charles Madison Mayes The Journal of the proceedings of SEc. -

Defeating Synarchism, and the Sublime

Click here for Full Issue of Fidelio Volume 13, Number 1-2, Spring-Summer 2004 continuing Martinist tradition of the French Revolution period’s Mesmer, Cagliostro, Joseph de Maistre, et al., is, once again, a leading issue of the current time. This was, originally, the banker-backed terrorist cult used to direct that great internal, systemic threat of 1789-1815 to France, and to the world of that time. This same banker-cult symbiosis was behind Mussolini’s dictatorship, and behind Adolf Hitler’s role during 1923-45. This was the threat posed by prominent pro-Synarchists inside the British Defeating Synarchism, Establishment, who, during the World War II setting of Dunkirk, had attempted to bring Britain and France into that planned alliance with Hitler, And the Sublime Mussolini, Franco, and Japan—which would, if achieved, have aimed to destroy the U.S.A. itself by aid n his essay “Of the Sublime,” a translation of of that consort of global naval power. That was the which appears in this issue of Fidelio, Friedrich enemy which we joined with Winston Churchill to ISchiller writes: “Great is he who overcomes the defeat, in World War II.” fearful. Sublime is he who does not fear it, even when Since the late 1700’s, the aim of Synarchism has he himself is overcome. ... One can show oneself to be been to prevent the spread of the Europe-engendered great in good fortune, sublime only in misfortune.” American Revolution, and ultimately, to destroy the On April 20, Mark Sonnenblick, a member of the United States through the simultaneous deployment of Schiller Institute and long-time associate of Lyndon ostensibly left-wing terrorists (anarchy), such as the and Helga LaRouche, passed away after a year-long, Jacobin terrorists of the French Revolution, and right- heroic battle for life, following wing fascists, beginning with unsuccessful open-heart the Emperor Napoleon surgery. -

THE NEW FACE of SYNARCHISM the Synarchy's Political

Page 40 The New Citizen April 2004 Defeat the Synarchists—Fight for a National Bank THE LIBERAL PARTY: THE NEW FACE OF SYNARCHISM “It might sound melodramatic to suggest that in 1951 Australian fascism’s headquarters were in ‘the Lodge’ Canberra, but that is not so very far from the truth.” —Dr. Andrew Moore, The Right Road? A History of Right-wing Politics in Australia The Synarchy’s Political Parties he fascist citizens leagues and Ttheir associated militias were inextricably intertwined with what historians call the “non-Labor” parties. These parties, such as the Nationalists of the 1920s, the Unit- ed Australia Party of the 1930s, and the Liberal Party from the 1940s until today, have never been anything but thinly-dis- guised fronts for a tiny cabal of financiers who created them in the first place. Like their storm troop- er associates in the Old Guard, the New Guard and the League for National Security, these parties were created for one reason: to stop the national banking, pro-nation Joseph “Honest Joe” Lyons, Prime state policies of the old ALP. Minister 1931-39. The financiers who controlled the Nationalist Party were gath- the financiers faced a real chal- ered in a secretive clique called lenge, due to a shift in the federal the National Union, based in Mel- ALP’s policy in early 1931, fol- bourne. Even the understated Age lowing the election of Jack Lang reported in 1927 on “the capture in NSW in October 1930. of the National machine by the In July 1930, when Scullin was secret and conservative National in London and E.G. -

Mexico's Cristero Rebellion

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 30, Number 29, July 25, 2003 EIRFeature MEXICO’S CRISTERO REBELLION Synarchism, the Spanish Falange, and the Nazis by William F. Wertz, Jr. This article is dedicated to the memory of Carlos Cota. It was tendom College in Virginia—a cesspool of Buckley family- prepared with the assistance of Cruz del Carmen Moreno connected Spanish Carlism—argued, for example in her book de Cota. Christ and the Americas, that the Cristero Rebellion was justi- fied, and that even though not victorious in the short term, it The purpose of this article is to give the potential youth leader had a positive historical effect, as evidenced by the fact that in Mexico and elsewhere knowledge of the way in which Pope John Paul II visited Mexico in the 1990s. As she put it: Synarchism has been used to try to prevent Mexico in particu- “The blood of the martyrs of the Revolution had borne fruit.” lar from developing as an independent sovereign nation-state, The reason that the views of an otherwise obscure North- as part of a worldwide community of sovereign nation-states ern Virginia cult figure like Anne Carroll are important on mutually committed to the promotion of the general welfare this question, is that she is part of the synarchist circles of of their respective populations through economic develop- Christendom College and the William F. Buckley family in ment. This article is necessitated by the renewed threat to the United States and in Mexico, which have targetted Lyndon both Mexico and the United States, among other nations, that LaRouche, who is the leading opponent of Synarchism in the today’s Synarchists—centered in the United States around world today. -

The Nazi-Instigated National Synarchist Union of Mexico

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 31, Number 27, July 9, 2004 EIRFeature WHAT IT MEANS FOR TODAY The Nazi-Instigated National Synarchist Union of Mexico Part 1, by William F. Wertz, Jr. When in July 2003, the leaders of the Ibero-American Solidarity Movement (MSIA)—founded in 1992 as a Trojan horse within the LaRouche movement— resigned from association with LaRouche over the issue of synarchism. Lyndon LaRouche warned that the MSIA’s controllers centered around Spain’s leading Francoist, Blas Pin˜ar, represent an Hispanic terrorist threat against the United States in behalf of the circles of Vice President Dick Cheney. The fact that Samuel Huntington, who promoted the Clash of Civilizations which has been the operative principle behind Cheney’s war in Iraq, has since authored a book, Who Are We?, which promotes a clash of civilizations between what he describes as the “Anglo- Protestant” culture of the United States and the primarily Mexican Hispanization of the U.S. Southwest, underscores the danger of another Sept. 11, under Hispanic cover. The March 11, 2004 train bombings in Madrid, and former Spanish Prime Minister Jose´ Marı´a Aznar’s warning that he is certain that there will be a terrorist incident in the United States before the U.S. elections, further point to the danger LaRouche identified last year, of a Reichstag Fire-type terrorist attack under His- panic cover, as part of a desperate effort to keep the besieged Cheney-centered neo- cons in power. The purpose of this article is to document the precedent for such a danger in the history of the Unio´n Nacional Sinarquista (UNS—National Synarchist Union) in Mexico, an organization created in 1937 by the Nazis, operating through the Spanish Falange and in conjunction with the Japanese. -

The Roosevelt Syndrome

Click here for Full Issue of Fidelio Volume 12, Number 3, Fall 2003 U.S., as “Synarchism: Nazi/Communist.” This Synarchist association, steered by a consortium of private family banking interests, was the creator and controller of a network of fascist governments including Mussolini’s Italy, Hitler’s Germany, Franco’s The Roosevelt Spain, and the Vichy and Laval governments of war- time France, and, also, a network of Nazi Party-run Syndrome Synarchists, coordinated through Spain, and subversive movements run from Mexico on south, throughout South America. This same Synarchist The following excerpt is taken from a statement entitled, network is the agency behind those so-called neo- “The DLC Wanes: Sewers Are Often Suburban,” issued conservatives, grouped around Cheney and Rumsfeld, by Lyndon LaRouche on July 29, 2003 in his capacity as a which has used the clearly intended effect of Sept. 11, Democratic pre-candidate for the U.S. Presidency. We 2001, to virtually take over the U.S. government’s publish this excerpt as our editorial in this issue of Fidelio, domestic and foreign policies. This Synarchist faction because it so succinctly identifies the primary threat to the is the present political enemy which every U.S. patriot world today as coming from the Synarchist circles of Vice must be prepared to defeat; any different view is not President Dick Cheney. At the only a foolish one, but also a same time, it identifies the only potentially fatal error, an alternative to such a threat today EDITORIAL error now already as the impeachment of Cheney threatening our constitutional and his Straussian “chicken- form of government. -

What Is Synarchism?

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 32, Number 3, January 21, 2005 This occult freemasonic conspiracy, is found among both nominally left-wing and also extreme right-wing fac- tions such as the editorial board of the Wall Street Journal, What Is Synarchism? the Mont Pelerin Society, and American Enterprise Insti- tute and Hudson Institute, and the so-called integrist far “Synarchism” is a name adopted during the Twentieth right inside the Catholic clergy. The underlying authority Century for an occult freemasonic sect, known as the Mar- behind these cults is a contemporary network of private tinists, based on worship of the tradition of the Emperor banks of that medieval Venetian model known as fondi. Napoleon Bonaparte. During the interval from the early The Synarchist Banque Worms conspiracy of the wartime 1920s through 1945, it was officially classed by U.S.A. 1940s, is merely typical of the role of such banking inter- and other nations’ intelligence services under the file name ests operating behind sundry fascist governments of that of “Synarchism: Nazi/Communist,” so defined because of period. its deploying simultaneously both ostensibly opposing The Synarchists originated in fact among the immedi- pro-communist and extreme right-wing forces for encir- ate circles of Napoleon Bonaparte; veteran officers of clement of a targetted government. Twentieth-Century and Napoleon’s campaigns spread the cult’s practice around later fascist movements, like most terrorist movements, the world. G.W.F. Hegel, a passionate admirer of Bona- are all Synarchist creations. parte’s image as Emperor, was the first to supply a fascist Synarchism was the central feature of the organization historical doctrine of the state.