The Sinarquista Movement with Special Reference To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I. Background Information the Cristero War Or Cristero

Historical Crisis Committee: Cristero War Members of the Dais: Myrna del Mar González & Gabriel García CSIMNU: September 23 & 24, 2016 I. Background Information The Cristero War or Cristero Rebellion (1926–1929), otherwise called La Cristiada, was a battle in many western Mexican states against the secularist, hostile to Catholic, and anticlerical strategies of the Mexican government. The defiance was set off by order under President Plutarco Elías Calles of a statute to authorize the anticlerical articles of the Mexican Constitution of 1917 (otherwise called the Calles Law). Calles tried to wipe out the force of the Catholic Church and associations subsidiary with it as an organization, furthermore smothering well known religious festivals. The gigantic prominent provincial uprising was implicitly upheld by the Church progressive system and was helped by urban Catholic backing. US Ambassador Dwight W. Morrow expedited transactions between the Calles government and the Church. The administration made a few concessions; the Church pulled back its support for the Cristero contenders and the contention finished in 1929. It can be seen as a noteworthy occasion in the battle among Church and State going back to the nineteenth century with the War of Reform, however, it can likewise be translated as the last real laborer uprising in Mexico taking after the end of the military period of the Mexican Revolution in 1920. II. Church-State Conflict The Mexican Revolution (1910–20) remains the biggest clash in Mexican history. The fall of Dictator Porfirio Díaz unleashed disarray with numerous battling groups and areas. The Catholic Church and the Díaz government had gone to a casual modus vivendi 1Whereby the State did not uphold the anticlerical articles of the liberal Constitution of 1857, and additionally did not cancel them. -

The Mexican-American Press and the Spanish Civil War”

Abraham Lincoln Brigades Archives (ALBA) Submission for George Watt Prize, Graduate Essay Contest, 2020. Name: Carlos Nava, Southern Methodist University, Graduate Studies. Chapter title: Chapter 3. “The Mexican-American Press and The Spanish Civil War” Word Count: 8,052 Thesis title: “Internationalism In The Barrios: Hispanic-Americans and The Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939.” Thesis abstract: The ripples of the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) had a far-reaching effect that touched Spanish speaking people outside of Spain. In the United States, Hispanic communities –which encompassed Puerto Ricans, Cubans, Mexicans, Spaniards, and others— were directly involved in anti-isolationist activities during the Spanish Civil War. Hispanics mobilized efforts to aid the Spanish Loyalists, they held demonstrations against the German and Italian intervention, they lobbied the United States government to lift the arms embargo on Spain, and some traveled to Spain to fight in the International Brigades. This thesis examines how the Spanish Civil War affected the diverse Hispanic communities of Tampa, New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. Against the backdrop of the war, this paper deals with issues regarding ethnicity, class, gender, and identity. It discusses racism towards Hispanics during the early days of labor activism. It examines ways in which labor unions used the conflict in Spain to rally support from their members to raise funds for relief aid. It looks at how Hispanics fought against American isolationism in the face of the growing threat of fascism abroad. CHAPTER 3. THE MEXICAN-AMERICAN PRESS AND THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR During the Spanish Civil War, the Mexican-American press in the Southwest stood apart from their Spanish language counterparts on the East Coast. -

Antichrist Conspiracy Inside the Devil’S Lair

Antichrist Conspiracy Inside the Devil’s Lair Why do the heathen rage, and the people imagine a vain thing? The kings of the earth set themselves, and the rulers take counsel together, against the LORD, and against his anointed, saying, Let us break their bands asunder, and cast away their cords from us. He that sitteth in the heavens shall laugh: the Lord shall have them in derision. (Psalms 2:1-4 AV) Revised Fourteenth Edition Copyright © 1999, 2005 by Edward Hendrie The author hereby grants a limited license to copy and disseminate this book in whole or in part, provided that there is no material alteration to the text and any excerpts identify the book and give notice that they are excerpts from the larger work. All other rights are reserved. All Scripture references are to the Authorized (King James) Version of the Holy Bible, unless otherwise indicated. Email: ed[at]antichristconspiracy[dot]com (My email address is written that way in order to defeat spam spiders from obtaining the address online and sending out spam email to the address. To email me simply replace the [at] with @ and the [dot] with .) Web site: http://www.antichristconspiracy.com “To the only wise God our Saviour, be glory and majesty, dominion and power, both now and ever. Amen.” Jude 1:25. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ..................................................................1 1. Conspiracy.............................................................2 2. Satan’s Religion.........................................................5 3. God’s Word............................................................6 4. Creation and Salvation Through God’s Word..................................8 5. God Preserves His Word..................................................8 6. The Roman Catholic Attack on God’s Word...................................9 7. -

The Cristero War and Mexican Collective Memory

History in the Making Volume 13 Article 5 January 2020 The Movement that Sinned Twice: The Cristero War and Mexican Collective Memory Consuelo S. Moreno CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making Part of the Latin American History Commons Recommended Citation Moreno, Consuelo S. (2020) "The Movement that Sinned Twice: The Cristero War and Mexican Collective Memory," History in the Making: Vol. 13 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making/vol13/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in History in the Making by an authorized editor of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Articles The Movement that Sinned Twice: The Cristero War and Mexican Collective Memory By Consuelo S. Moreno Abstract: Many scattered occurrences in Mexico bring to memory the 1926-1929 Cristero War, the contentious armed struggle between the revolutionary government and the Catholic Church. After the conflict ceased, the Cristeros and their legacy did not become part of Mexico’s national identity. This article explores the factors why this war became a distant memory rather than a part of Mexico’s history. Dissipation of Cristero groups and organizations, revolutionary social reforms in the 1930s, and the intricate relationship between the state and Church after 1929 promoted a silence surrounding this historical event. Decades later, a surge in Cristero literature led to the identification of notable Cristero figures in the 1990s and early 2000s. -

Synarchism, Sinarquismo, Synarquismo, Sinarchismo, Synarchismo, Sinarchie, Synarchie, Sinarchia, Synarchía, Sinarq

On Synarchy (Synarchism, Sinarquismo, Synarquismo, Sinarchismo, Synarchismo, Sinarchie, Synarchie, Sinarchia, Synarchía, Sinarquia, Synarquia, Sinarkia, Synarkia; Global Synarchist Movement) Copyright © 2003 Joseph George Caldwell. All rights reserved. Posted at Internet website http://www.foundationwebsite.org. May be copied or reposted for non-commercial use, with attribution to author and website. (13 July 2003, updated 27 July 2003; title updated 15 April 2009) Contents On Synarchy (Synarchism, Sinarquismo, Synarquismo, Sinarchismo, Synarchismo, Sinarchie, Synarchie, Sinarchia, Synarchía, Sinarquia, Synarquia, Sinarkia, Synarkia; Global Synarchist Movement) .......................................................... 1 Origins of the Term Synarchy and Its Derivatives (synarchism, synarchic, synarchical, synarchist) .................. 1 Synarchist Concepts Since the Time of Saint-Yves ............ 26 Some Concluding Remarks ................................................ 32 Origins of the Term Synarchy and Its Derivatives (synarchism, synarchic, synarchical, synarchist) In my writings on a long-term-sustainable system of planetary management for Earth, I have variously used the terms “Platonic” and “synarchic” to describe the nature of the planetary management system. Neither of these terms is exactly “right” to describe the system that I am proposing. Plato wrote his Republic in the context of the Greek city- state of 500 BC, and Saint-Yves d’Alveydre developed his concept of Synarchy in the late 1800s. Since Saint-Yves’ concept is most closely aligned with what I propose for the management system of the planetary management organization, that is the term that I generally use. It should be recognized, however, that the terms synarchy and synarchism have been used by many different people over the years, and the particular concept that the user had in mind may differ from what I have proposed. -

The Mexican Political Fracture and the 1954 Coup in Guatemala (The Beginnings of the Cold War in Latin America)

Culture & History Digital Journal 4(1) June 2015, e006 eISSN 2253-797X doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3989/chdj.2015.006 The Mexican political fracture and the 1954 coup in Guatemala (The beginnings of the cold war in Latin America) Soledad Loaeza El Colegio de México [email protected] Submitted: 2 September 2014. Accepted: 16 February 2015 ABSTRACT: This article challenges two general assumptions that have guided the study of Mexican foreign policy in the last four decades. First, that from this policy emerges national consensus; and, secondly that between Mexico and the US there is a “special relation” thanks to which Mexico has been able to develop an autonomous foreign policy. The two assumptions are discussed in light of the impact on Mexican domestic politics of the 1954 US- sponsored military coup against the government of government of Guatemala. In Mexico, the US intervention re- opened a political fracture that had first appeared in the 1930’s, as a result of President Cárdenas’radical policies that divided Mexican society. These divisions were barely dissimulated by the nationalist doctrine adopted by the gov- ernment. The Guatemalan Crisis brought some of them into the open. The Mexican President, Adolfo Ruiz Cortines’ priority was the preservation of political stability. He feared the US government might feel the need to intervene in Mexico to prevent a serious disruption of the status quo. Thus, Ruiz Cortines found himself in a delicate position in which he had to solve the conflicts derived from a divided elite and a fractured society, all this under the pressure of US’ expectations regarding a secure southern border. -

The Vatican II Sect Vs. the Catholic Church on Non-Catholics Receiving Holy Communion

239 19. The Vatican II sect vs. the Catholic Church on non-Catholics receiving Holy Communion Pope Pius VIII, Traditi Humilitati (# 4), May 24, 1829: “Jerome used to say it this way: he who eats the Lamb outside this house will perish as did those during the flood who were not with Noah in the 1 ark.” Benedict XVI giving Communion to the public heretic, Bro. Roger Schutz,2 the Protestant founder of Taize on April 8, 2005 In the preceding sections on the heresies of Vatican II and John Paul II, we covered that they both teach the heresy that non-Catholics may lawfully receive Holy Communion. It’s important to summarize the Vatican II sect’s official endorsement of this heretical teaching here for handy reference: Vatican II Vatican II document, Orientalium Ecclesiarum # 27: “Given the above-mentioned principles, the sacraments of Penance, Holy Eucharist, and the anointing of the sick may be conferred on eastern Christians who in good faith are separated from the Catholic Church, if they make the request of their own accord and are properly disposed.”3 Non-Catholics receiving Communion 240 Paul VI solemnly confirming Vatican II Antipope Paul VI, at the end of every Vatican II document: “EACH AND EVERY ONE OF THE THINGS SET FORTH IN THIS DECREE HAS WON THE CONSENT OF THE FATHERS. WE, TOO, BY THE APOSTOLIC AUTHORITY CONFERRED ON US BY CHRIST, JOIN WITH THE VENERABLE FATHERS IN APPROVING, DECREEING, AND ESTABLISHING THESE THINGS IN THE HOLY SPIRIT, AND WE DIRECT THAT WHAT HAS THUS BEEN ENACTED IN SYNOD BE PUBLISHED TO GOD’S GLORY.. -

Brief History of the Cristero War and Mexico's Struggle for Religious Freedom the Role of the U.S. Knights of Columbus in Resp

Brief History of the Cristero War and Mexico’s Struggle for Religious Freedom When President Plutarco Calles took over as president of Mexico in 1924, he did not want the Catholic Church to be a part of any moral teachings to its citizens. He did not want God to be a part of anyone’s life. He wanted to bring Mexico’s population to belong to a Socialist state, and wanted to ensure that all citizens were going to be educated under the government’s dictatorship and secular mindset. He also wanted to ensure that only the government would have the freedom to form the minds of its citizens and insisted that the Church was poisoning the minds of the people. He implemented the “Law for Reforming the Penal Code” or “Calles’ Law”, which severely restricted the free practice of religion in Mexico. Priests or religious wearing clerical garb in public, and clerics who spoke out against the government could be jailed for five years. The Mexican bishops suspended public religious services in response to the law, and supported an economic boycott against the government. Violence soon erupted, as bands of Catholic peasants battled federal forces. Priests were shot and hung, Church property seized, and many religious institutions closed. The Cristeros’ battle cry was “Viva Cristo Rey!” (“Long live Christ the King!”). During the three-year war (1926-1929), approximately 90,000 people were killed. There are a total of 35 Martyrs who have been canonized. The Role of the U.S. Knights of Columbus in Response to the Cristero War In August of 1926, days after the Calles Law took effect, the U.S. -

Mexico's 2006 Elections

Mexico’s 2006 Elections -name redacted- October 3, 2006 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov RS22462 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Mexico’s 2006 Elections Summary Mexico held national elections for a new president and congress on July 2, 2006. Conservative Felipe Calderón of the National Action Party (PAN) narrowly defeated Andrés Manuel López Obrador of the leftist Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) in a highly contested election. Final results of the presidential election were only announced after all legal challenges had been settled. On September 5, 2006, the Elections Tribunal found that although business groups illegally interfered in the election, the effect of the interference was insufficient to warrant an annulment of the vote, and the tribunal declared PAN-candidate Felipe Calderón president-elect. PRD candidate López Obrador, who rejected the Tribunal’s decision, was named the “legitimate president” of Mexico by a National Democratic Convention on September 16. The electoral campaign touched on issues of interest to the United States including migration, border security, drug trafficking, energy policy, and the future of Mexican relations with Venezuela and Cuba. This report will not be updated. See also CRS Report RL32724, Mexico-U.S. Relations: Issues for Congress, by (name redacted) and (name redacted); CRS Report RL32735,Mexico-United States Dialogue on Migration and Border Issues, 2001-2006, by (name redacted); and CRS Report RL32934, U.S.-Mexico Economic Relations: -

A Guide to the Leadership Elections of the Institutional Revolutionary

A Guide to the Leadership Elections of the Institutional Revolutionary Party, the National Action Party, and the Democratic Revolutionary Party George W. Grayson February 19, 2002 CSIS AMERICAS PROGRAM Policy Papers on the Americas A GUIDE TO THE LEADERSHIP ELECTIONS OF THE PRI, PAN, & PRD George W. Grayson Policy Papers on the Americas Volume XIII, Study 3 February 19, 2002 CSIS Americas Program About CSIS For four decades, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has been dedicated to providing world leaders with strategic insights on—and policy solutions to—current and emerging global issues. CSIS is led by John J. Hamre, formerly deputy secretary of defense, who has been president and CEO since April 2000. It is guided by a board of trustees chaired by former senator Sam Nunn and consisting of prominent individuals from both the public and private sectors. The CSIS staff of 190 researchers and support staff focus primarily on three subject areas. First, CSIS addresses the full spectrum of new challenges to national and international security. Second, it maintains resident experts on all of the world’s major geographical regions. Third, it is committed to helping to develop new methods of governance for the global age; to this end, CSIS has programs on technology and public policy, international trade and finance, and energy. Headquartered in Washington, D.C., CSIS is private, bipartisan, and tax-exempt. CSIS does not take specific policy positions; accordingly, all views expressed herein should be understood to be solely those of the author. © 2002 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. -

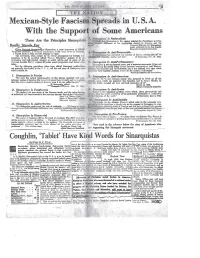

Mexican-Style Fascism Spreads in U. S. A. with the Support of Some Americans

PM, SUNDAY, MAY .21, 1944 THE NAT ION Mexican-Style Fascism Spreads in U. S. A. With the Support of Some Americans . 5. Smarquum Is Nationalistic These Are the Principles Sinarquismi "I submit that. Sinarquism is the a g selected by Providence to bring about Mexico's fulfilment of her appr to destby, America and the world." Preseneis littering del Sinorquinno, leaflet published by the Los Angeles or Sinarquism, a mass movement of 900,00 Sioarontst Regional Committee. mem rs is -we aces counterpart of the Neu Party in Germany, 6. Sinarquism Is Anti•Dernocratic e Fascist Party in IItaly and the Falange in Spain. "It [democracy has corrupted our concept of liberty, tutting.maa lais The movement, when judged by its official propaganda for foreign con- El Stnarquista, Nov. 27. 194L sumption, or by Its so-milled official 'Sixteen Principles," appears to be an relations with morality, justice and law." booffensive and high-minded attempt at social reform—just as many of the National Socialist Party's original 25 points sound progressive and decent even 7. Sinorquisth Is Anti.Parliamentary today. "Sinarquism Is not an electoral party, not a sectarian movement. It hos not But the following quotations, taken from official Sinarquist publications come to prolong the 'sordid bitter contest between 'conservatives' and 'liberals. not generally distributed in the U. S, A., tell the real stray of Sinarquism and between 'reactionaries' and 'revolutionists,' for it has realized with clear vision what it stands for. that from these horrible conflicts derive all the nation's nu.s• forhtnes." Prsoencis lit:laded del Sinorquiiisto. -

2014 National History Bee National Championships Round

2014 National History Bee National Championships Bee Round 4 BEE ROUND 4 1. A military defeat of this person was commemorated in an orchestral piece that was premiered at a charity concert for wounded soldiers, along with its composer's seventh symphony. A song commemorating the "battle and defeat" of this person is part of the Hary Janos (HAH-ree YAY-nosh) Suite. Ferdinand Ries related that a composer tore the title page of another of his pieces in half to omit a mention of this person. For the point, name this person to whom Beethoven originally dedicated his Eroica Symphony before he was crowned Emperor of France. ANSWER: Napoleon Bonaparte [or Napoleon I; prompt on Bonaparte] 020-13-94-22101 2. In November 2013, an interview between this man and Eugenio Scalfari of La Repubblica was taken down from a website when it was found to contain inaccuracies. A statement this man made in May 2013 was quickly refuted by Thomas Rosica in an article for ZENIT. This man caused a stir in March 2013 at the Casal del Marmo detention center when two young women and ten young men had their feet washed by him. For the point, name this Argentinian man who in March of 2013 became the first Jesuit to hold a title relinquished weeks earlier by Benedict XVI. ANSWER: Pope Francis I [or Jorge Mario Bergoglio] 023-13-94-22102 3. Comedian Eddie Cantor's show was taken off the air after Cantor denounced this man, who was not Henry Ford. The Attorney General sought to revoke the mailing privileges of this man's newspaper, Social Justice, which in 1938 reprinted all of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.