An Example of Laser Plasma Extreme Ultraviolet Generation- Christopher S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extreme Ultraviolet Source Based on Microwave Discharge Produced Plasma Using Cavity Resonator

D2-PMo-1 APPC12 The 12th Asia Pacific Physics Conference Extreme Ultraviolet Source based on microwave discharge produced plasma using cavity resonator S. Tashima, M. Ohnishi, H. Osawa, W. Hugrass a Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Faculty of Engineering Science, Kansai University, 3-3-35 Yamate-cho, Suita, Osaka 564-8680, Japan aSchool of Computing and Information Systems, University of Tasmania, Locked Bag 1359, Launceston, Tasmania 7250, Australia [email protected] Extreme ultra violet (EUV) lithography is a leading technology for the production of the next-generation chips with small features. The 13.5-nm EUV radiation can be obtained using either discharge-produced plasma (DPP) or laser-produced plasma (LPP) sources. Because the EUV radiation is strongly absorbed by all known materials, the entire EUV scanner system must be in a vacuum environment. The debris and the tin vapor generated in some EUV sources may cause contamination of the EUV mirrors and the silicon wafers. The microwave discharge produced plasma (MDPP) source invented at Kansai University does not produce debris because it is electrode-less and the working gas is Xe.. Figure 1 shows the photo of MDPP. The microwave frequency is 2.45 GHz, the maximum power (Prf ) is 6 kW and the cavity mode is TM110. The Xe gas is fed in a glass tube with inner diameter 3 mm. The EUV radiation is measured using a calorie meter and EUV spectroscopy. The preliminary experiments show that the Figure 1 The system of microwave discharge produced plasma system MDPP produces pulsed EUV radiation of 10 W/4π str. -

Extreme-Ultraviolet Frequency Combs for Precision Metrology and Attosecond Science

REVIEW ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-020-00741-3 Extreme-ultraviolet frequency combs for precision metrology and attosecond science Ioachim Pupeza 1,2 ✉ , Chuankun Zhang3,4, Maximilian Högner 1 and Jun Ye 3,4 ✉ Femtosecond mode-locked lasers producing visible/infrared frequency combs have steadily advanced our understanding of fundamental processes in nature. For example, optical clocks employ frequency-comb techniques for the most precise measure- ments of time, permitting the search for minuscule drifts of natural constants. Furthermore, the generation of extreme-ultraviolet attosecond bursts synchronized to the electric field of visible/infrared femtosecond pulses affords real-time measurements of electron dynamics in matter. Cavity-enhanced high-order harmonic generation sources uniquely combine broadband vacuum- and extreme-ultraviolet spectral coverage with multimegahertz pulse repetition rates and coherence properties akin to those of frequency combs. Here we review the coming of age of this technology and its recent applications and prospects, including precision frequency-comb spectroscopy of electronic and potentially nuclear transitions, and low-space-charge attosecond-temporal-resolution photoelectron spectroscopy with nearly 100% temporal detection duty cycle. he control over broadband visible/near-infrared (VIS/NIR) ωN = ω0 +Nωr. Here ωr = 2π/Tr and ω0 are two frequencies in the electromagnetic waves, such as uniquely enabled by laser radiofrequency domain, corresponding to the inverse round-trip Tarchitectures employing mode-locked oscillators, lies at the time Tr of the optical pulse inside the mode-locked oscillator and heart of most advanced optical metrologies. The temporal inter- to an overall comb-offset frequency, respectively, and N is an play between gain, loss, dispersion and nonlinear propagation in integer. -

A Theoretical Investigation

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 6 September 2019 doi:10.20944/preprints201909.0069.v1 ON THE EXTENSION OF COMPTON’S EXPERIMENT:A THEORETICAL INVESTIGATION Amal Pushp Fellow, The Royal Astro. Soc. Burlington House, Piccadilly London W1J 0BQ [email protected] September 6, 2019 ABSTRACT With new discoveries and insights in atomic and optical physics, the field of spectroscopy is advancing to a new level with applications ranging from material science to astronomy. We here propose a theoretical description of a potential new phenomenon resulting from the extension of Compton’s experiment on the scattering of high energy photons through atomic electrons. How the proposed phenomenon can be tested experimentally is discussed in the paper as well.∗ ∗The Idea of the paper is to be presented as part of an International Conference talk (ICECMP-2019) © 2019 by the author(s). Distributed under a Creative Commons CC BY license. Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 6 September 2019 doi:10.20944/preprints201909.0069.v1 SEPTEMBER 6, 2019 1 Introduction Therefore, we get, In 1923, A.H. Compton made a discovery which showed h h h the remarkable transformation that X rays undergo when δλ = ; δλ = ; :::::; δλ = 1 m c 2 m c β m c they are scattered by atoms [1, 2]. Some 5 years later, Sir e e e CV Raman, an Indian physicist at the Indian Association or for the Cultivation of Science (IACS), discovered along δλ = δλ1 + δλ2 + ::: + δλβ (4) with his students, that this scattering involving the change in wavelength of the radiation is also possible for visible or light [3]. -

Compensation of Extreme Ultraviolet Lithography Image Field Edge Effects Through Optical Proximity Correction

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 2-2014 Compensation of Extreme Ultraviolet Lithography Image Field Edge Effects Through Optical Proximity Correction Chris Maloney Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Maloney, Chris, "Compensation of Extreme Ultraviolet Lithography Image Field Edge Effects Through Optical Proximity Correction" (2014). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMPENSATION OF EXTREME ULTRAVIOLET LITHOGRAPHY IMAGE FIELD EDGE EFFECTS THROUGH OPTICAL PROXIMITY CORRECTION by CHRIS MALONEY A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Science in Microelectronic Engineering Kate Gleason College of Engineering Department of Electrical and Microelectronic Engineering Rochester Institute of Technology Rochester, NY February 2014 Author: _________________________________________________________________ Chris Maloney Approved by: ____________________________________________________________ Robert Pearson, Ph.D. Approved by: ____________________________________________________________ Bruce W. Smith, Ph.D. Approved by: ____________________________________________________________ Dale Ewbank, Ph.D. Approved by: ____________________________________________________________ -

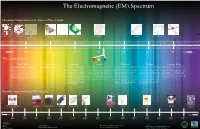

Radio Waves: Microwaves: Infrared: Visible: Ultraviolet: X-Rays: Gamma

The Electromagnetic (EM) Spectrum Hawaiian Comparisons to the Sizes of Wavelengths: Aloha Tower Aloha Stadium Hale Kamehameha Point of a Needle Plant Cell Bacteria Protein Water Molecule Atom (Hawaiian House) Butterfly 3 -2 -5 -6 -8 -10 -12 Longer 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 Shorter Wavelength (Meters): Radio Waves: Microwaves: Infrared: Visible: Ultraviolet: X-Rays: Gamma Rays: Radio waves have the longest wavelength in the EM Since microwaves can penetrate haze, light Infrared light has a range of wavelengths Visible light waves are the only waves in spec- Ultraviolet light is invisible to the human As the wavelengths of the spectrum de- Gamma rays have the smallest wavelength, spectrum. As implied, radio waves bring music to ra- rain, snow, clouds and smoke, these waves like visible light. “Near infrared” light is trum that humans can see. These waves are eyes, but some insects, like bumblebees, have crease, the energy increases, such as how but have the most energy out of all of the other dios, but they also provide signals to cell phones, tele- are ideal for viewing the Earth from space. closest in wavelength to visible light and seen in a range of colors with red having the proven to be able to see ultraviolet light. The x-rays tend to act more like a particle than waves in the spectrum. These waves are gener- visions, etc. Radio waves are received at an estimate The wavelength of micro waves in a mi- “far infrared” is closer to the microwave re- longest wavelength and violet (purple) having ultraviolet part of the spectrum is divided into a wave. -

Laser-Plasma Sources for Extreme-Ultraviolet Lithography

Laser-Plasma Sources for Extreme-Ultraviolet Lithography BJÖRN A. M. HANSSON Doctoral Thesis Stockholm, Sweden 2003 TRITA FYS 2003-56 ISSN 0280-316X KTH ISRN KTH/FYS/--03:56--SE SE-100 44 Stockholm ISBN 91-7283-658-X SWEDEN Akademisk avhandling som med tillstånd av Kungl Tekniska högskolan framlägges till offentlig granskning för avläggande av teknologie doktorsexamen fredagen den 19 december 2003 kl. 10.00 i Kollegiesalen, Administrationsbyggnaden, Kungl Tekniska högskolan, Valhallavägen 79, Stockholm. °c Björn A. M. Hansson, november 2003 Tryck: Universitetsservice US AB iii Abstract This thesis describes the development and characterization of a liquid- xenon-jet laser-plasma source for extreme-ultraviolet (EUV) radiation. It is shown how this source may be suitable for production-scale EUV lithography (EUVL). EUVL is one of the main candidates to succeed deep-ultraviolet (DUV) lithography for large-scale manufacturing of integrated circuits (IC). However, a major obstacle towards the realization of EUVL is the current unavailability of a source meeting the tough requirements on especially power and clean- liness for operation in an EUVL stepper. The liquid-xenon-jet laser-plasma concept has key advantages that may make it suitable for EUVL since, e.g., its plasma consists only of the inert noble gas xenon and since the liquid- jet target technology enables plasma operation at large distances from the source-hardware thereby reducing sputtering and to allowing for high-power operation. At the beginning of the work described in this thesis, a spatial insta- bility of the liquid-xenon-jet made stable operation of a plasma at practical distances from the nozzle orifice difficult. -

Spectral Purification and Infrared Light Recycling in Extreme Ultraviolet Lithography Sources

Spectral purification and infrared light recycling in extreme ultraviolet lithography sources Muharrem Bayraktar,1,* Fred A. van Goor,1 Klaus J. Boller,1 and Fred Bijkerk1,2,3 1Laser Physics and Nonlinear Optics Group, MESA + Research Institute for Nanotechnology, University of Twente, P.O. Box 217, 7500 AE, Enschede, The Netherlands 2Industrial Focus Group XUV Optics, MESA + Research Institute for Nanotechnology, University of Twente, P.O. Box 217, 7500 AE, Enschede, The Netherlands 3Dutch Institute for Fundamental Energy Research, P.O. Box 1207, 3430 BE, Nieuwegein, The Netherlands *[email protected] Abstract: We present the design of a novel collector mirror for laser produced plasma (LPP) light sources to be used in extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography. The design prevents undesired infrared (IR) drive laser light, reflected from the plasma, from reaching the exit of the light source. This results in a strong purification of the EUV light, while the reflected IR light becomes refocused into the plasma for enhancing the IR-to-EUV conversion. The dual advantage of EUV purification and conversion enhancement is achieved by incorporating an IR Fresnel zone plate pattern into the EUV reflective multilayer coating of the collector mirror. Calculations using Fresnel-Kirchhoff’s diffraction theory for a typical collector design show that the IR light at the EUV exit is suppressed by four orders of magnitude. Simultaneously, 37% of the reflected IR light is refocused back the plasma. ©2014 Optical Society of America OCIS codes: (050.1970) Diffractive optics; (220.3740) Lithography; (230.7408) Wavelength filtering devices; (260.3060) Infrared; (340.7480) X-rays, soft x-rays, extreme ultraviolet (EUV); (350.5400) Plasmas. -

X-Rays and Extreme Ultraviolet Radiation 2Nd Edition Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-06289-4 — X-Rays and Extreme Ultraviolet Radiation 2nd Edition Frontmatter More Information X-Rays and Extreme Ultraviolet Radiation With this fully updated second edition, you will gain a detailed understanding of the physics and applications of modern x-ray and extreme ultraviolet (EUV) radiation sources. Taking into account the most recent improvements in capabilities, coverage is expanded to include new chapters on free electron lasers (FELs), laser high harmonic generation (HHG), x-ray and EUV optics, and nanoscale imaging, a completely revised chapter on spatial and temporal coherence, and extensive discussion of the generation and applications of femtosecond and attosecond techniques. You will be guided step by step through the mathematics of each topic, with over 300 figures, 50 reference tables, and 600 equations enabling easy understanding of key concepts. Homework problems, a solutions manual for instructors, and links to YouTube lectures accompany the book online. This is the “go-to” guide for graduate students, researchers, and industry practitioners looking to grasp the fundamentals of x-ray and EUV interaction with matter, or expand their knowledge of this rapidly growing field. David Attwood is Professor Emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley. He is a co-founder of the Applied Science and Technology PhD program at Berkeley, and a Fellow of the American Physical Society and the Optical Society of America. He has published over 100 scientific papers and co-edited several books. Anne Sakdinawat is a scientist at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, where she leads a scientifically motivated imaging and nanofabrication group co-located at Stan- ford University. -

Super-Resolution Image Transfer by a Vortex-Like Metamaterial

Super-resolution image transfer by a vortex-like metamaterial Hui Yuan Dong,1,2 Jin Wang,1 Kin Hung Fung,3 and Tie Jun Cui4,∗ 1Department of Physics, Southeast University, Nanjing 211189, China 2School of Science, Nanjing University of Posts and Telecommunications, Nanjing 210003, China 3Department of Applied Physics, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China 4State Key Laboratory of Millimeter Waves, Department of Radio Engineering, Southeast University, Nanjing 210096, China ∗[email protected] Abstract: We propose a vortex-like metamaterial device that is capable of transferring image along a spiral route without losing subwavelength information of the image. The super-resolution image can be guided and magnified at the same time with one single design. Our design may provide insights in manipulating super-resolution image in a more flex- ible manner. Examples are given and illustrated with numerical simulations. © 2013 Optical Society of America OCIS codes: (120.4570) Optical design of instruments; (110.0180) Microscopy; (160.3918) Metamaterials. References and links 1. R. A. Shelby, D. R. Smith, and S. Schultz, “Experimental verification of a negative index of refraction,” Science 292, 77–79 (2001). 2. R. Liu, C. Ji, J. J. Mock, J. Y. Chin, T. J. Cui, and D. R. Smith, “Broadband ground-plane cloak,” Science 323, 366–369 (2009). 3. J. B. Pendry, “Negative refraction makes a perfect lens,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 3966–3969 (2000). 4. N. Fang, H. Lee, C. Sun, and X. Zhang, “Sub-diffraction-limited optical imaging with a silver superlens,” Science 308, 534–537 (2005). 5. T. Taubner, D. Korobkin, Y. -

Power Scaling of a Radiation Source for Extreme Ultraviolet Lithography

2 guarantees a comprehensive characterization of the radiation POWER SCALING OF source itself and the interrelations between parameterization A RADIATION SOURCE and EUV radiation generation. Of essential interest here are the plasma geometry, the beam characteristic in the EUV and FOR EXTREME ULTRAVIOLET the conversion efficiency of the electrically stored energy in LITHOGRAPHY (EUVL) EUV light. What was varied was, among others, the electrical current pulse form, given by the capacitance of the electrical circuit, the electrical pulse energy and the distribution of the Task tin vapor between the electrodes, which can be influenced by a pulsed trigger-laser with adjustable parameters. To produce computer chips of the future, based on EUV lithography (EUV = extreme ultraviolet), manufacturers need Result high-power radiation sources with a central wavelength of 13.5 nm. For several years, Fraunhofer ILT has been developing For the first time, a parameter space could be identified with such radiation sources in close cooperation with industry which the vacuum arc in tin vapor can fulfill the requirements partners. The technical basis for these sources is the vacuum upon a prospective production source. arc in tin vapor: here, in a pulsed electrical discharge, tin plasma is excited to emit characteristic radiation at 13.5 nm. Applications As a developmental goal for these radiation sources several kilowatts light power in a spectral bandwidth of 2 percent The technology will be chiefly used in EUV lithography around the central wavelength of 13.5 nm into half- space is either to expose wafers or in EUV metrology, e.g. in reticule challenged by the industry. -

Alcazar Katherine

Electromagnetic Waves: The Different Types and Importance for Our Daily Lives Presented by, Katie Alcazar Honors, PHY 131 Uses for daily life: Introduction: Microwaves have several important uses in our daily lives. One of these uses is microwaves the metal box that heats your food when you are in a rush or for convenience. This wasn’t the original use for microwaves at all, it was in 1946 when Percy Spencer an American engineer was walking past microwaves and realized that the This research paper will cover electromagnetic (EM) waves and their uses specifying on microwaves and chocolate bar in his pocket had melted which lead him to design the first microwave called the radarange. It was in ultraviolet waves. Electromagnetic waves have many common uses in your daily life that you might not even the year 1955 when Tappan first introduced a microwave for home use, yet it was still too big and expensive for realize. The point is to outline the EM spectrum and how it all works and comes together. Almost everyone uses a general home use. In the year 1967, was when microwaves truly started coming into homes after Amana microwave daily, but do they understand the application of these microwaves to heat food along with their other Corporation introduced the countertop microwave. From 1946 to 2020 microwaves have evolved a lot and have very important uses. Another electromagnetic wave that is important and contributes to our existence is ultraviolet become a more essential part of our daily life. There are a lot of other uses for microwaves other than the obvious waves. -

Extreme Ultraviolet Mask Roughness Effects in High Numerical Aperture Lithography Abstract 1. INTRODUCTION 2. MODELING MASK MULT

Extreme ultraviolet mask roughness effects in high numerical aperture lithography Patrick Naulleau, Yow-Gwo Wang, and Tom Pistor Center for X-ray Optics, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, California EECS, University of California, Berkeley, California Panoramic Technology Inc., Burlingame, California Abstract Given the reflective nature of extreme ultraviolet lithography and its extremely short operational wavelength, roughness of the optical surfaces is of significant concern. In particular, roughness in the mask multilayer leads to image plane speckle and ultimately patterned line-edge or line-width variability in the imaging process. Here we consider the implications of this effect for future high numerical aperture (NA) systems that are assumed to require anamorphic magnification projection optics. The results show significant anisotropic behavior at high NA as well as a substantial increase in relative patterned line variability in the shadowed direction when comparing 0.55 NA to 0.33 NA, despite the assumption of an anamorphic magnification system. The shadowed-direction patterned line variability is 2×2× larger than for unshadowed lines, and the majority of the increase in variability occurs in the low frequency regime. 1. INTRODUCTION Photolithography is a cost-effective method of manufacturing integrated circuits. In this process, a circuit pattern master is first patterned onto a mask, and then an optical reduction system is used to replicate demagnified images of the mask onto a silicon wafer. The image projected to the wafer is recorded in a photosensitive film and ultimately etched into the silicon wafer. To continue the push to ever smaller feature sizes, the industry is now transitioning to extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography systems.