Contentious Politics and the 25Th January Egyptian Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women and Participation in the Arab Uprisings: a Struggle for Justice

Distr. LIMITED E/ESCWA/SDD/2013/Technical Paper.13 26 December 2013 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMISSION FOR WESTERN ASIA (ESCWA) WOMEN AND PARTICIPATION IN THE ARAB UPRISINGS: A STRUGGLE FOR JUSTICE New York, 2013 13-0381 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper constitutes part of the research conducted by the Social Participatory Development Section within the Social Development Division to advocate the principles of social justice, participation and citizenship. Specifically, the paper discusses the pivotal role of women in the democratic movements that swept the region three years ago and the challenges they faced in the process. The paper argues that the increased participation of women and their commendable struggle against gender-based injustices have not yet translated into greater freedoms or increased political participation. More critically, in a region dominated by a patriarchal mindset, violence against women has become a means to an end and a tool to exercise control over society. If the demands for bread, freedom and social justice are not linked to discourses aimed at achieving gender justice, the goals of the Arab revolutions will remain elusive. This paper was co-authored by Ms. Dina Tannir, Social Affairs Officer, and Ms. Vivienne Badaan, Research Assistant, and has benefited from the overall guidance and comments of Ms. Maha Yahya, Chief, Social Participatory Development Section. iii iv CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... iii Chapter I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. GENDERING ARAB REVOLUTIONS: WHAT WOMEN WANT ......................... 2 A. The centrality of gender to Arab revolutions............................................................ 2 B. Participation par excellence: Activism among Arab women.................................... 3 III. CHANGING LANES: THE STRUGGLE OVER WOMEN’S BODIES ................. -

The Iron Fist Vs. the Microchip

Journal of Strategic Security Volume 5 Number 2 Volume 5, No. 2: Summer Article 6 2012 The Iron Fist vs. the Microchip Elizabeth I. Bryant Georgetown University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss pp. 1-26 Recommended Citation Bryant, Elizabeth I.. "The Iron Fist vs. the Microchip." Journal of Strategic Security 5, no. 2 (2012) : 1-26. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.5.2.1 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/vol5/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Strategic Security by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Iron Fist vs. the Microchip Abstract This article focuses on how information and communication technology (ICT) influences the behavior of authoritarian regimes. Modern information and communication tools can challenge authoritarian rule, but the same technology can be used by savvy regimes to buttress their own interests. The relationship of technology and political power is more accurately conceived of as a contested space in which competitors vie for dominance and as a neutral tool that is blind to value judgments of good versus evil. A realist understanding of the nature and limits of technology is vital in order to truly evaluate how ICT impacts the relative strength of intransigent regimes fighting to stay in power and those on the disadvantaged side of power agitating for change. -

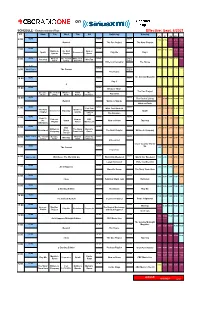

Siriusxm-Schedule.Pdf

on SCHEDULE - Eastern Standard Time - Effective: Sept. 6/2021 ET Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Saturday Sunday ATL ET CEN MTN PAC NEWS NEWS NEWS 6:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 4:00 3:00 Rewind The Doc Project The Next Chapter NEWS NEWS NEWS 7:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 4:00 Quirks & The Next Now or Spark Unreserved Play Me Day 6 Quarks Chapter Never NEWS What on The Cost of White Coat NEWS World 9:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 8:00 Pop Chat WireTap Earth Living Black Art Report Writers & Company The House 8:37 NEWS World 10:00 9:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 9:00 World Report The Current Report The House The Sunday Magazine 10:00 NEWS NEWS NEWS 11:00 10:00 9:00 8:00 7:00 Day 6 q NEWS NEWS NEWS 12:00 11:00 10:00 9:00 8:00 11:00 Because News The Doc Project Because The Cost of What on Front The Pop Chat News Living Earth Burner Debaters NEWS NEWS NEWS 1:00 12:00 The Cost of Living 12:00 11:00 10:00 9:00 Rewind Quirks & Quarks What on Earth NEWS NEWS NEWS 1:00 Pop Chat White Coat Black Art 2:00 1:00 12:00 11:00 10:00 The Next Quirks & Unreserved Tapestry Spark Chapter Quarks Laugh Out Loud The Debaters NEWS NEWS NEWS 2:00 Ideas in 3:00 2:00 1:00 12:00 11:00 Podcast Now or CBC the Spark Now or Never Tapestry Playlist Never Music Live Afternoon NEWS NEWS NEWS 3:00 CBC 4:00 3:00 2:00 1:00 12:00 Writers & The Story Marvin's Reclaimed Music The Next Chapter Writers & Company Company From Here Room Top 20 World This Hr The Cost of Because What on Under the NEWS NEWS 4:00 WireTap 5:00 4:00 3:00 2:00 1:00 Living News Earth Influence Unreserved Cross Country Check- NEWS NEWS Up 5:00 The Current -

Suez Canal Development Project: Egypt's Gate to the Future

Economy Suez Canal Development Project: Egypt's Gate to the Future President Abdel Fattah el-Sissi With the Egyptian children around him, when he gave go ahead to implement the East Port Said project On November 27, 2015, President Ab- Egyptians’ will to successfully address del-Fattah el-Sissi inaugurated the initial the challenges of careful planning and phase of the East Port Said project. This speedy implementation of massive in- was part of a strategy initiated by the vestment projects, in spite of the state of digging of the New Suez Canal (NSC), instability and turmoil imposed on the already completed within one year on Middle East and North Africa and the August 6, 2015. This was followed by unrelenting attempts by certain interna- steps to dig out a 9-km-long branch tional and regional powers to destabilize channel East of Port-Said from among Egypt. dozens of projects for the development In a suggestive gesture by President el of the Suez Canal zone. -Sissi, as he was giving a go-ahead to This project is the main pillar of in- launch the new phase of the East Port vestment, on which Egypt pins hopes to Said project, he insisted to have around yield returns to address public budget him on the podium a galaxy of Egypt’s deficit, reduce unemployment and in- children, including siblings of martyrs, crease growth rate. This would positively signifying Egypt’s recognition of the role reflect on the improvement of the stan- of young generations in building its fu- dard of living for various social groups in ture. -

Chapter 5 Existing Condition Survey

CHAPTER 5 EXISTING CONDITION SURVEY FEASIBILITY STUDY ON HIGH PRIORITY URBAN TOLL EXPRESSWAYS IN CAIRO FINAL REPORT CHAPTER 5 EXISTING CONDITION SURVEY 5.1 INTRODUCTION The urban expressway will act as a component of the existing road network and it will not function alone. Therefore, data of ordinary at-grade road network is indispensable when an urban expressway network is formulated. To obtain such data, existing condition survey is implemented. The survey takes into consideration three main existing conditions which are: - Existing road conditions by undertaken Road Inventory Surveys. - Existing soil conditions by undertaking Geotechnical Investigations. - Existing geometric conditions by undertaking Topographical Surveys. The scope of this Study includes carrying out Feasibility Study for the Expressway Sections E1-2, E2-2 and E3-1 and Pre-Feasibility Study for Sections E1-1, E2-1, E3-2 and E3-3. Theses sections which belong to Expressways E1 (6th of October), E2 (15th of May) and E3 (Autostrad/Salah Salem) are shown in Figure 5.1-1. Figure 5.1-1 Expressways under Study 5 - 1 FEASIBILITY STUDY ON HIGH PRIORITY URBAN TOLL EXPRESSWAYS IN CAIRO FINAL REPORT Hereafter and based on the scope of the Study, the objectives, terms of references, tasks and results are described. 5.2 ROAD INVENTORY SURVEY 5.2.1 Adopted Method for Data Collection The survey covered the following tasks: 1. Topographic Survey for profiles and cross sections at every 200 m and where the layout changes along the existing routes of E1 and E2, as well as the proposed routes E1-2, E2-2, and E3-1 which are under the feasibility study. -

RFR Template

THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF ADMINISTRATION AND FINANCE DIVISION OF CAPITAL ASSET MANAGEMENT AND MAINTENANCE ONE ASHBURTON PLACE 15TH FLOOR BOSTON, MA 02108 Request for Response (RFR) Commonwealth of Massachusetts Energy Intelligence System COMMBUYS Bid#: Agency Document Number: DCP2127E AD1 UNSPC Code: 2.12.2021 Please Note: This is a single document associated with a complete Bid (also referred to as Solicitation) that can be found on COMMBUYS (www.COMMBUYS.com). All Bidders are responsible for reviewing and adhering to all information, forms and requirements for the entire Bid, which are all incorporated into the Bid. Bidders may also contact the COMMBUYS Helpdesk at [email protected] or the COMMBUYS Helpline at 1-888-MA-STATE. The Helpline is staffed from 8:00 AM to 5:00 PM Monday through Friday Eastern Standard or Daylight time, as applicable, except on federal, state and Suffolk county holidays. Document Sensitivity Level: High during development; Low once published. Revised: December 23, 2014 1 RFR INTRODUCTION AND GENERAL DESCRIPTION ....................................................... 1 1.1 Procurement Scope and Description ....................................................................................... 1 1.2 Background Information ........................................................................................................ 1 1.3 Applicable Procurement Law ................................................................................................. 2 1.4 Number of Awards ................................................................................................................. -

Questionnaire on Use of Legislation to Regulate Activities of Human Rights Defenders – Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights Defenders

Questionnaire on use of legislation to regulate activities of human rights defenders – Special Rapporteur on the situation of Human Rights Defenders Response concerning Egypt by: Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies and Nazra for Feminist Studies (Egypt) Date of submission : 15/06/2012 1. a) Please indicate if your country has a specific legal framework, laws or regulations that aim to facilitate or protect the activities and work of human rights defenders. Please cite the names of such laws or regulations in full. - There is no such legal framework or specific laws that can facilitate the work of Human Rights defenders, although provisions of the constitutional declaration assert the free practice of the basic rights and the freedoms; this is a contradiction that will be elaborated in detail below. b) Please indicate how these laws and regulations are in line with the international human rights standards, including, but not limited to, the declaration on human rights defenders. As stated in response to question 1a, there are no specific laws or regulations that could protect the work of the HRDs. On the contrary, the NGO law, for example law number 84/2002, do not comply with the international human rights standards nor with the declaration on human rights defenders. The same applies for the laws regulating the right to freedom of assembly and the freedom of expression. c) Please also indicate what legal or administrative safeguards are put in place to prevent baseless legal action against and/or prosecution of human rights defenders for undertaking their legitimate work - There are no legal or administrative safeguards to prevent baseless legal actions(s) against human rights defenders for undertaking their work. -

Performative Revolution in Egypt: an Essay in Cultural Power

Alexander, Jeffrey C. "Performative Revolution in Egypt." Performative Revolution in Egypt: An Essay in Cultural Power. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2011. 1–86. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 27 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781472544841.ch-001>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 27 September 2021, 11:19 UTC. Copyright © Jeffrey C. Alexander 2011. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. ISCUSSIONS about revolutions, from the Dsocial scientifi c to the journalistic, almost invariably occur in the realist mode. Whether nominalist or collectivist, materialist, political or institutional, it seems a point of honor to maintain that it is real issues, real groups, and real interests, and how these have aff ected relative power vis-à-vis the state, that determine who makes revolutions, who opposes them, and who wins at the end of the day. At the very beginning of the “25 January Revolution” in Egypt, a reporter for the New York Times traced its temporal and spatial origins to the naturalistic causal power of a single event: “The beating of a young businessman named Khaled Said last year [in Alexandria] led to weeks of demonstrations against police brutality.”2 Said, a twenty- eight-year-old businessman, allegedly had fi lmed proof of police corruption; he was dragged from an internet café on 6 June 2010, tortured, and beaten to death. Addressing the broader social -

Mobilisation Et Répression Au Caire En Période De Transition (Juin 2010-Juin 2012)

Mobilisation et r´epressionau Caire en p´eriode de transition (juin 2010-juin 2012) Nadia Aboushady To cite this version: Nadia Aboushady. Mobilisation et r´epressionau Caire en p´eriode de transition (juin 2010-juin 2012). Science politique. 2013. <dumas-00955609> HAL Id: dumas-00955609 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-00955609 Submitted on 4 Mar 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L'archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destin´eeau d´ep^otet `ala diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publi´esou non, lished or not. The documents may come from ´emanant des ´etablissements d'enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche fran¸caisou ´etrangers,des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou priv´es. Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne UFR 11- Science politique Programme M2 recherche : Sociologie et institutions du politique Master de science politique Mobilisation et répression au Caire en période de transition (juin 2010-juin 2012) Nadia Abou Shady Mémoire dirigé par Isabelle Sommier juin 2013 Sommaire Sommaire……………………………………………………………………………………...2 Liste d‟abréviation…………………………………………………………………………….4 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………5 Premier Chapitre. De la mort de Khaled Saïd au « vendredi de la colère » : répression étatique et mobilisation contestataire ascendante………………………………………...35 Section 1 : L’origine du cycle de mobilisation contestataire……………………………………...36 -

Egypt | Freedom House

Egypt | Freedom House http://www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2013/egypt About Us DONATE Blog Contact Us Subscribe REGIONS ISSUES Reports Programs Initiatives News Experts Events Donate FREEDOM IN THE WORLD Egypt Freedom in the World 2013 OVERVIEW: 2013 Political instability and protests continued throughout 2012, as a SCORES contentious transition from military to civilian rule was followed by heated debate over the unilateral actions of the new Islamist-dominated STATUS government. Elections for the People’s Assembly, Egypt’s lower house of parliament, were completed in January 2012, with nearly 70 percent of the new chamber held by Islamist parties that were illegal before the ouster of authoritarian president Hosni Mubarak in early 2011. However, the People’s Assembly was dismissed in mid-June, after various electoral FREEDOM RATING laws were ruled unconstitutional in what many described as a power struggle between the judiciary and the political establishment. Mohamed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood won a presidential runoff later in June, and in November he claimed extensive executive powers in a decree that CIVIL LIBERTIES he defended as necessary to ensure the adoption of a new constitution in a chaotic political environment. The resulting constitution, which opponents criticized as a highly problematic document written by an unrepresentative and overwhelmingly Islamist constituent assembly, was POLITICAL RIGHTS approved in a mid-December referendum, but its passage failed to quell deep mistrust and tensions between liberal and Islamist political factions at year’s end. Egypt formally gained independence from Britain in 1922 and acquired full sovereignty in 1952. After leading a coup that overthrew the monarchy, Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser ruled until his death in 1970. -

Mints – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY

No. TRANSPORT PLANNING AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT MiNTS – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE MASTER PLAN FOR NATIONWIDE TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORT 11 TRANSPORT SURVEY FINDINGS March 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. ALMEC CORPORATION EID KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL JR - 12 039 No. TRANSPORT PLANNING AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT MiNTS – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE MASTER PLAN FOR NATIONWIDE TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORT 11 TRANSPORT SURVEY FINDINGS March 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. ALMEC CORPORATION EID KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL JR - 12 039 USD1.00 = EGP5.96 USD1.00 = JPY77.91 (Exchange rate of January 2012) MiNTS: Misr National Transport Study Technical Report 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Item Page CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................................1-1 1.1 BACKGROUND...................................................................................................................................1-1 1.2 THE MINTS FRAMEWORK ................................................................................................................1-1 1.2.1 Study Scope and Objectives .........................................................................................................1-1 -

Failure of Muslim Brotherhood Movement on the Scene of Government in Egypt and Its Political Future

International Journal of Asian Social Science, 2015, 5(7): 394-406 International Journal of Asian Social Science ISSN(e): 2224-4441/ISSN(p): 2226-5139 journal homepage: http://www.aessweb.com/journals/5007 FAILURE OF MUSLIM BROTHERHOOD MOVEMENT ON THE SCENE OF GOVERNMENT IN EGYPT AND ITS POLITICAL FUTURE Rasoul Goudarzi1† --- Azhdar Piri Sarmanlou2 1,2Department of International Relations, Political Science Faculty, Islamic Azad University Central Tehran Branch, Tehran, Iran ABSTRACT After occurrence of public movements in Egypt that led the Egyptian Islamist movement of Muslim Brotherhood to come to power in ruling scene of this country, Mohamed Morsi as a candidate of this party won in the first democratic presidency elections in this country and after coming to power, he took a series of radical measures both in domestic and international scenes, which have caused him to be ousted in less than one year. The present essay is intended to reveal this fact based on theoretical framework of overthrowing government of Ibn Khaldun by proposing various reasons and documentations about several aspects of ousting of Morsi. Similarly, it indicates that with respect to removing this movement from Egypt political scene and confiscation of their properties, especially after the time when Field Marshal Abdel Fattah El-Sisi came to power as a president, so Muslim Brotherhood should pass through a very tumultuous path to return to political scene in Egypt compared to past time, especially this movement has lost noticeably its public support and backing. © 2015 AESS Publications. All Rights Reserved. Keywords: Muslim brotherhood, Army, Egypt, Political situation. Contribution/ Originality The paper's primary contribution is study of Mohamed Morsi‟s radical measures both in domestic and international scenes in Egypt, which have caused him to be ousted in less than one year.