Egypt | Freedom House

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mobilisation Et Répression Au Caire En Période De Transition (Juin 2010-Juin 2012)

Mobilisation et r´epressionau Caire en p´eriode de transition (juin 2010-juin 2012) Nadia Aboushady To cite this version: Nadia Aboushady. Mobilisation et r´epressionau Caire en p´eriode de transition (juin 2010-juin 2012). Science politique. 2013. <dumas-00955609> HAL Id: dumas-00955609 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-00955609 Submitted on 4 Mar 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L'archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destin´eeau d´ep^otet `ala diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publi´esou non, lished or not. The documents may come from ´emanant des ´etablissements d'enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche fran¸caisou ´etrangers,des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou priv´es. Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne UFR 11- Science politique Programme M2 recherche : Sociologie et institutions du politique Master de science politique Mobilisation et répression au Caire en période de transition (juin 2010-juin 2012) Nadia Abou Shady Mémoire dirigé par Isabelle Sommier juin 2013 Sommaire Sommaire……………………………………………………………………………………...2 Liste d‟abréviation…………………………………………………………………………….4 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………5 Premier Chapitre. De la mort de Khaled Saïd au « vendredi de la colère » : répression étatique et mobilisation contestataire ascendante………………………………………...35 Section 1 : L’origine du cycle de mobilisation contestataire……………………………………...36 -

The Egyptian Revolution and American Media Coverage

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by AUC Knowledge Fountain (American Univ. in Cairo) American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Theses and Dissertations 2-1-2012 Media darlings: the Egyptian revolution and American media coverage Rebecca Fox Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds Recommended Citation APA Citation Fox, R. (2012).Media darlings: the Egyptian revolution and American media coverage [Master’s thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/1022 MLA Citation Fox, Rebecca. Media darlings: the Egyptian revolution and American media coverage. 2012. American University in Cairo, Master's thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/1022 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American University in Cairo School of Global Affairs and Public Policy MEDIA DARLINGS: THE EGYPTIAN REVOLUTION AND AMERICAN MEDIA COVERAGE A Thesis Submitted to Middle East Studies Program in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Rebecca Suzanne Fox under the supervision of Dr. Benjamin Geer 11/2012 ABSTRACT Title: Media Darlings: The Egyptian Revolution and American Media Coverage Throughout the first few months of 2011, a handful of protesters dominated mainstream American media coverage of the Egyptian Revolution. Activists such as Wael Ghonim and Gigi Ibrahim were called “the Facebook youth” and “digital revolutionaries”. -

Al Jazeera's Expansion: News Media Moments and Growth in Australia

Al Jazeera’s Expansion: News Media Moments and Growth in Australia PhD thesis by publication, 2017 Scott Bridges Institute of Governance and Policy Analysis University of Canberra ABSTRACT Al Jazeera was launched in 1996 by the government of Qatar as a small terrestrial news channel. In 2016 it is a global media company broadcasting news, sport and entertainment around the world in multiple languages. Devised as an outward- looking news organisation by the small nation’s then new emir, Al Jazeera was, and is, a key part of a larger soft diplomatic and brand-building project — through Al Jazeera, Qatar projects a liberal face to the world and exerts influence in regional and global affairs. Expansion is central to Al Jazeera’s mission as its soft diplomatic goals are only achieved through its audience being put to work on behalf of the state benefactor, much as a commercial broadcaster’s profit is achieved through its audience being put to work on behalf of advertisers. This thesis focuses on Al Jazeera English’s non-conventional expansion into the Australian market, helped along as it was by the channel’s turning point coverage of the 2011 Egyptian protests. This so-called “moment” attracted critical and popular acclaim for the network, especially in markets where there was still widespread suspicion about the Arab network, and it coincided with Al Jazeera’s signing of reciprocal broadcast agreements with the Australian public broadcasters. Through these deals, Al Jazeera has experienced the most success with building a broadcast audience in Australia. After unpacking Al Jazeera English’s Egyptian Revolution “moment”, and problematising the concept, this thesis seeks to formulate a theoretical framework for a news media turning point. -

Toward Muslim Democracies Saad Eddin Ibrahim

Toward Muslim Democracies Saad Eddin Ibrahim Journal of Democracy, Volume 18, Number 2, April 2007, pp. 5-13 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2007.0025 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/214438 Access provided by your local institution (27 Feb 2017 15:55 GMT) TOWARD MUSLIM DEMOCRACIES Saad Eddin Ibrahim Saad Eddin Ibrahim, founder and chairman of the Ibn Khaldun Center for Development Studies and professor of political sociology at the American University in Cairo, delivered the 2006 Seymour Martin Lipset Lecture on Democracy in the World (see box on p. 6). Dr. Ibrahim has been one of the Arab world’s most prominent spokesmen on behalf of democracy and human rights. His 2000 arrest and subsequent seven- year sentence for accepting foreign funds without permission and “tar- nishing” Egypt’s image sparked a loud outcry from the international community. In 2003, Egypt’s High Court of Cassation declared his trial improper and cleared him of all charges. He is the author, coauthor, or editor of more than thirty-five books in Arabic and English, including Egypt, Islam, and Democracy: Critical Essays (2002). The late Seymour Martin Lipset was one of the greatest men I have known in my life as an academic and as an activist. He was the first person I was introduced to—through his seminal 1960 book Political Man1—during my first year of graduate school at UCLA, in 1963. As a matter of fact, I had thought that I was going to be his student before I learned, much to my disappointment, that he was teaching at another campus of the University of California. -

Framing of Political Forces in Liberal, Islamist and Government Newspapers in Egypt: a Content Analysis

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Theses and Dissertations 6-1-2012 Framing of political forces in liberal, islamist and government newspapers in Egypt: A content analysis Noha El-Nahass Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds Recommended Citation APA Citation El-Nahass, N. (2012).Framing of political forces in liberal, islamist and government newspapers in Egypt: A content analysis [Master’s thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/296 MLA Citation El-Nahass, Noha. Framing of political forces in liberal, islamist and government newspapers in Egypt: A content analysis. 2012. American University in Cairo, Master's thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/296 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American University in Cairo School of Global Affairs and Public Policy Framing of Political Forces in Liberal, Islamist and government newspapers in Egypt: A content analysis A Thesis Submitted to Journalism & Mass Communication department In partial fulfillment of the requirements for The degree of Master of Arts By Noha El-Nahass Under the supervision of Dr. Naila Hamdy Spring 2016 1 Dedication I dedicate this thesis to the journalists who lost their lives while covering the political turbulences in Egypt, may their sacrifices enlighten the road and give the strength to their colleagues to continue reflecting the truth and nothing but the truth. -

Interview with Dr. Saad Eddin Ibrahim Daniel Benaim

The Fletcher School Online Journal for issues related to Southwest Asia and Islamic Civilization Spring 2006 Interview with Dr. Saad Eddin Ibrahim Daniel Benaim In the weeks leading up to Egypt's No. You can’t have democracy without being Presidential election, I had the opportunity to inclusive of everybody, so long as people are interview Dr. Saad Eddin Ibrahim. Dr. Ibrahim is respectful of the rules of the game. perhaps Egypt's best-known dissident intellectual and the Founder and Chairman of the Ibn Khaldun One critic worried that you were describing Center for Development Studies in Cairo, where I the Islamists that you wish for, rather than those was a Summer Fellow in 2005. In June 2000, Dr. that you see. How would you integrate the Ibrahim and two dozen of his associates were Muslim Brotherhood into Egyptian politics while arrested and jailed on charges ranging from assuring that they play by the rules of the game? defrauding the European Union to disseminating Isn’t there a danger that the process would be information harmful to Egypt's interests. After a irreversible? three-year ordeal during which Dr. Ibrahim (62 years old at the time) was sentenced to seven years The Egyptian Constitution includes all kinds of hard labor--all charges against him were of built-in safeguards. I suggested the armed forces dismissed by Egypt's highest court and he was and the constitution serve as the safeguards of released from prison in 2003. Sitting in his office in pluralism, of civil government, and of regular old a beautiful Islamic villa in Cairo's Mokattam democratic aims. -

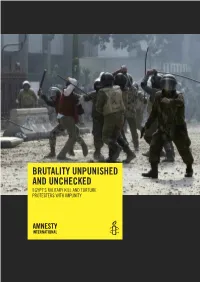

Brutality Unpunished and Unchecked

brutality unpunished and unchecked EGYPT’S MILITARY KILL AND TORTURE PROTESTERS WITH IMPUNITY amnesty international is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the universal declaration of human rights and other international human rights standards. we are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2012 by amnesty international ltd peter benenson house 1 easton street london wc1X 0dw united kingdom © amnesty international 2012 index: mde 12/017/2012 english original language: english printed by amnesty international, international secretariat, united kingdom all rights reserved. this publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. the copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. to request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover phot o: egyptian soldiers beating a protester during clashes near the cabinet offices by cairo’s tahrir square on 16 december 2011. © mohammed abed/aFp/getty images amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................5 2. MASPERO PROTESTS: ASSAULT OF COPTS.............................................................11 3. CRACKDOWN ON CABINET OFFICES SIT-IN.............................................................17 4. -

Egypt's Uncertain Departure from Neo-Authoritarianism

MEDITERRANEAN PAPER SERIES 2011 TRANSITION TO WHAT: EGYPT’S UNCERTAIN DEPARTURE FROM NEO-AUTHORITARIANIsm Daniela Pioppi Maria Cristina Paciello Issandr El Amrani Philippe Droz-Vincent © 2011 The German Marshall Fund of the United States. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the German Marshall Fund of the United States GMF. Please direct inquiries to: The German Marshall Fund of the United States 1744 R Street, NW Washington, DC 20009 T 1 202 683 2650 F 1 202 265 1662 E [email protected] This publication can be downloaded for free at www.gmfus.org/publications. Limited print copies are also available. To request a copy, send an e-mail to [email protected]. GMF Paper Series The GMF Paper Series presents research on a variety of transatlantic topics by staff, fellows, and partners of the German Marshall Fund of the United States. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of GMF. Comments from readers are welcome; reply to the mailing address above or by e-mail to [email protected]. About GMF The German Marshall Fund of the United States GMF is a non-partisan American public policy and grantmaking institu- tion dedicated to promoting better understanding and cooperation between North America and Europe on transatlantic and global issues. GMF does this by supporting individuals and institutions working in the transatlantic sphere, by convening leaders and members of the policy and business communities, by contributing research and analysis on transatlantic topics, and by pro- viding exchange opportunities to foster renewed commitment to the transatlantic relationship. -

The Kefaya Movement

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. The Kefaya Movement A Case Study of a Grassroots Reform Initiative Nadia Oweidat, Cheryl Benard, Dale Stahl, Walid Kildani, Edward O'Connell, Audra K. -

A Politics of Inclusion: an Interview with Saad Eddin Ibrahim

A Politics of Inclusion: An Interview with Saad Eddin Ibrahim Saad Eddin Ibrahim is Professor of Political Sociology at the American University in Cairo. He founded the Ibn Khaldun Center for Development Studies and is one of the Arab world’s most prominent spokesmen for democracy and human rights. Author, co-author, or editor of more than thirty-five books in Arabic and English, including Egypt, Islam and Democracy: Critical Essays (1996), he was arrested by the Mubarak regime in 2000 and sentenced to seven years’ hard labour for ‘tarnishing’ Egypt’s image. After an international outcry, Egypt’s High Court cleared him of all charges in 2003. In this interview he explores the fateful encounter of Islam and the Arab world with modernity and democracy, and assesses the prospects for Islamic reformation and Arab democratisation. He examines the symbiotic relationship between the region’s autocrats and theocrats, before turning to the prospects for progress in Iraq. The interview was conducted on 11 February 2007. Part 1: Personal and intellectual background Alan Johnson: Who and what have been the most important personal and intellectual influences in your life? Saad Eddin Ibrahim: As a youngster I was influenced by leaders from our national history and from the ‘third world’ – Gandhi, Nehru, Mao, Che and Nasser (whom I met at an early age but who later stripped me of my nationality and declared me persona non grata when I was in my twenties). These people shaped me positively and negatively – some became negative reference points. And my family was very influential. My uncles adhered to different political traditions, from Communism to the Muslim Brotherhood. -

Military Electoral Authoritarianism in Egypt

Please do not remove this page Military electoral authoritarianism in Egypt Aziz, Sahar F. https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643396150004646?l#13643549520004646 Aziz, S. F. (2017). Military electoral authoritarianism in Egypt. In Election Law Journal (Vol. 16, Issue 2, pp. 280–295). Rutgers University. https://doi.org/10.7282/T35142T3 This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/09/30 09:23:52 -0400 ELECTION LAW JOURNAL Volume 16, Number 2, 2017 Military Electoral Authoritarianism in Egypt Sahar F. Aziz1 Table of Contents I. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 2 II. Electoral Authoritarianism .................................................................................................................... 4 III. Elections Under Sadat and Mubarak ................................................................................................ 6 A. Sadat Introduces Multiparty Elections .............................................................................................. 7 B. Mubarak Promotes Civilian Electoral Authoritarianism ................................................................... 8 IV. From Revolution to Military Coup: General Sisi Becomes -

Social Media- a New Virtual Civil Society in Egypt? Abdulaziz Sharbatly

Social Media- a new Virtual Civil Society in Egypt? Abdulaziz Sharbatly This is a digitised version of a dissertation submitted to the University of Bedfordshire. It is available to view only. This item is subject to copyright. • Social Media - a new virtual civil society in Egypt? UNIVERSITY OF BEDFORDSHIRE 1 Social Media: a new virtual civil society in Egypt? by Abdulaziz Sharbatly A thesis submitted to the University of Bedfordshire in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Research Institute for Media, Arts & Performance Journalism & Communications Department 2 AbstractAbstractAbstract This project seeks to trace the power of social media in serving as a virtual civil society in the Arab world, focusing on Egypt as a case study. This study aims to explore the role of social media in mobilising Egyptian activists across generations, and particularly in reaching out to people under the age of 35 who constitute around 50 per cent of the population. Studies preceding the 2011 uprising reported that young Egyptians were politically apathetic and were perceived as incapable of bringing about genuine political changes. Drawing on a range of methods and data collected from focus groups of young people under the age of 35, interviews with activists (across generations and gender), and via a descriptive web feature analysis, it is argued that online action has not been translated into offline activism. The role of trust in forming online networks is demonstrated, and how strong ties can play a pivotal role in spreading messages via social media sites. Activists relied on social media as a medium of visibility; for those who were not active in the political sphere, social media have been instrumental in raising their awareness about diverse political movements and educating them about the political process, after decades of political apathy under Mubarak’s regime.