CAMERON-DISSERTATION-2017.Pdf (6.705Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of the Perkins School of Theology

FROM THE COLLECTIONS OF Bridwell Library PERKINS SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY SOUTHERN METHODIST UNIVERSITY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 http://www.archive.org/details/historyofperkinsOOgrim A History of the Perkins School of Theology A History of the PERKINS SCHOOL of Theology Lewis Howard Grimes Edited by Roger Loyd Southern Methodist University Press Dallas — Copyright © 1993 by Southern Methodist University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America FIRST EDITION, 1 993 Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to: Permissions Southern Methodist University Press Box 415 Dallas, Texas 75275 Unless otherwise credited, photographs are from the archives of the Perkins School of Theology. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Grimes, Lewis Howard, 1915-1989. A history of the Perkins School of Theology / Lewis Howard Grimes, — ist ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-87074-346-5 I. Perkins School of Theology—History. 2. Theological seminaries, Methodist—Texas— Dallas— History. 3. Dallas (Tex.) Church history. I. Loyd, Roger. II. Title. BV4070.P47G75 1993 2 207'. 76428 1 —dc20 92-39891 . 1 Contents Preface Roger Loyd ix Introduction William Richey Hogg xi 1 The Birth of a University 1 2. TheEarly Years: 1910-20 13 3. ANewDean, a New Building: 1920-26 27 4. Controversy and Conflict 39 5. The Kilgore Years: 1926-33 51 6. The Hawk Years: 1933-5 63 7. Building the New Quadrangle: 1944-51 81 8. The Cuninggim Years: 1951-60 91 9. The Quadrangle Comes to Life 105 10. The Quillian Years: 1960-69 125 11. -

Loyalty, Or Democracyat Home?

WW II: loyalty, or democracy at home? continued from page 8 claimed 275,000 copies sold each week, The "old days," when Abbott 200,000 of its National edition, 75,000 became the first black publisher to of its local edition. Mrs. Robert L. Vann establish national circulation by who said she'd rather be known as soliciting Pullman car porters and din- Robert L. Vann's widow than any other ing car waiters to get his paper out, man's wife reported that the 17 were gone. Once, people had been so various editions of the Pittsburgh V a of anxious about getting the Defender that lW5 Yt POWBCX I IT A CMCK WA KIMo) Courier had circulation 300,000. Pf.Sl5 Jm happened out ACtw mE Other women leaders of they just sent Abbott money in the mail iVl n HtZx&Vif7JWaP rjr prominent the NNPA were Miss Olive . .coins glued to cards with table numerous. syrup. Abbott just dumped all the Diggs was business manager of Anthony money and cards in a big barrel to Overton's Chicago Bee. She was elected separate the syrup and paper from the th& phone? I wbuWfi in 1942 as an executive committee cash. What Abbott sold his readers was w,S,75ods PFKvSi member, while Mrs. Vann was elected an idea catch the first train and come eastern vice president. They were the out of the South. first women to hold elected office in the n New publishers with new ideas were I NNPA. coming to the fore. W.A. -

Center for Public History

Volume 8 • Number 2 • spriNg 2011 CENTER FOR PUBLIC HISTORY Oil and the Soul of Houston ast fall the Jung Center They measured success not in oil wells discovered, but in L sponsored a series of lectures the dignity of jobs well done, the strength of their families, and called “Energy and the Soul of the high school and even college graduations of their children. Houston.” My friend Beth Rob- They did not, of course, create philanthropic foundations, but ertson persuaded me that I had they did support their churches, unions, fraternal organiza- tions, and above all, their local schools. They contributed their something to say about energy, if own time and energies to the sort of things that built sturdy not Houston’s soul. We agreed to communities. As a boy, the ones that mattered most to me share the stage. were the great youth-league baseball fields our dads built and She reflected on the life of maintained. With their sweat they changed vacant lots into her grandfather, the wildcatter fields of dreams, where they coached us in the nuances of a Hugh Roy Cullen. I followed with thoughts about the life game they loved and in the work ethic needed later in life to of my father, petrochemical plant worker Woodrow Wilson move a step beyond the refineries. Pratt. Together we speculated on how our region’s soul—or My family was part of the mass migration to the facto- at least its spirit—had been shaped by its famous wildcat- ries on the Gulf Coast from East Texas, South Louisiana, ters’ quest for oil and the quest for upward mobility by the the Valley, northern Mexico, and other places too numerous hundreds of thousands of anonymous workers who migrat- to name. -

BIGGERS, JOHN THOMAS, 1924-2001. John Biggers Papers, 1950-2001

BIGGERS, JOHN THOMAS, 1924-2001. John Biggers papers, 1950-2001 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Collection Stored Off-Site All or portions of this collection are housed off-site. Materials can still be requested but researchers should expect a delay of up to two business days for retrieval. Descriptive Summary Creator: Biggers, John Thomas, 1924-2001. Title: John Biggers papers, 1950-2001 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1179 Extent: 31 linear feet (62 boxes), 6 oversized papers boxes and 2 oversized papers folders (OP), 2 oversized bound volumes (OBV), 1 extra-oversized paper (XOP), and AV Masters: .25 linear feet (1 box) Abstract: Papers of African American mural artist and professor John Biggers including correspondence, photographs, printed materials, professional materials, subject files, writings, and audiovisual materials documenting his work as an artist and educator. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Use copies have not been made for audiovisual material in this collection. Researchers must contact the Rose Library at least two weeks in advance for access to these items. Collection restrictions, copyright limitations, or technical complications may hinder the Rose Library's ability to provide access to audiovisual material. Collection stored off-site. Researchers must contact the Rose Library in advance to access this collection. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. -

Transactional Analysis in Psychotherapy

TThhee BBooookk ooff EEvvaann:: TThhee wwoorrkk aanndd lliiffee ooff EEvvaann MMccAArraa SShheerrrraarrdd Keith Tudor | Editor E-book edition The Book of Evan: The work and life of Evan McAra Sherrard Editor: Keith Tudor E-book (2020) ISBN: 9781877431–88-3 Printed edition (2017) ISBN: 9781877431-78-4 © Keith Tudor 2017, 2020 Keith Tudor asserts his moral right to be known as the Editor of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electrical, mechanical, photocopying, recording, digital or otherwise without the prior written permission of Resource Books Ltd. Waimauku, Auckland, New Zealand [email protected] | www.resourcebooks.co.nz Contents The Book of Evan: The work and life of Evan McAra Sherrard Keith Tudor | Editor Contents Foreword. Isabelle Sherrard Poroporoaki: A bridge between two worlds. Haare Williams Introduction to the e-book edition. Keith Tudor Introduction. Keith Tudor The organisation and structure of the book Acknowledgements References Part I. AGRICULTURE Introduction. Keith Tudor Chapter 1. Papers related to agriculture. Evan M. Sherrard Biology (2008) Film review of The Ground We Won (2015) References Chapter 2. Memories of Evan from Lincoln College and from a farm. Alan Nordmeyer, Robin Plummer, and Colin Wrennall Alan Nordmeyer writes Robin Plummer writes Colin Wrennall writes Part II. MINISTRY Introduction. Keith Tudor Chapter 3. Sermons. Evan M. Sherrard St. Patrick’s Day (1963) Sickness unto death (1965) Good grief (1966) When things get out of hand (1966) Rains or refugees? (1968) Unconscious influence (n.d.) Faithful winners (1998) Epiphany (2006) Colonialism (2008) Jesus and Paul — The consummate political activists (2009) A modern man faces Pentecost (2010) Ash Wednesday (2011) Healing (2011) Killed by a dancing girl (2012) Self-love (2012) Geering and Feuerbach (2014) Chapter 4. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 157 WASHINGTON, MONDAY, MARCH 14, 2011 No. 38 House of Representatives The House met at noon and was I have visited Japan twice, once back rifice our values and our future all in called to order by the Speaker pro tem- in 2007 and again in 2009 when I took the name of deficit reduction. pore (Mr. CAMPBELL). my oldest son. It’s a beautiful country; Where Americans value health pro- f and I know the people of Japan to be a tections, the Republican CR slashes resilient, generous, and hardworking funding for food safety inspection, DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO people. In this time of inexpressible community health centers, women’s TEMPORE suffering and need, please know that health programs, and the National In- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- the people of South Carolina and the stitutes of Health. fore the House the following commu- people of America stand with the citi- Where Americans value national se- nication from the Speaker: zens of Japan. curity, the Republican plan eliminates WASHINGTON, DC, May God bless them, and may God funding for local police officers and March 14, 2011. continue to bless America. firefighters protecting our commu- I hereby appoint the Honorable JOHN f nities and slashes funding for nuclear CAMPBELL to act as Speaker pro tempore on nonproliferation, air marshals, and this day. FUNDING THE FEDERAL Customs and Border Protection. Where JOHN A. BOEHNER, GOVERNMENT Americans value the sacrifice our men Speaker of the House of Representatives. -

Meet Me at the Flagpole: Thoughts About Houston’S Legacy of Obscurity and Silence in the Fight of Segregation and Civil Right Struggles

Meet Me at the Flagpole: Thoughts about Houston’s Legacy of Obscurity and Silence in the fight of Segregation and Civil Right Struggles Bernardo Pohl Abstract This article focuses on the segregated history and civil right movement of Houston, using it as a case study to explore more meaningfully the teaching of this particular chapter in American history. I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made straight and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed and all flesh shall see it together. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. I remember the day very clearly. It was an evening at Cullen Auditorium at Uni- versity of Houston. It was during the fall of 2002, and it was the end of my student teach- ing. Engulfed in sadness, I sat alone and away from my friends. For me, it was the end of an awesome semester of unforgettable moments and the start of my new teaching career. I was not really aware of the surroundings; I did not have a clue about what I was about to experience. After all, I just said yes and agreed to another invitation made by Dr. Cam- eron White, my mentor and professor. I did not have any idea about the play or the story that it was about to start. The word “Camp Logan” did not evoke any sense of familiarity in me; it did not resonate in my memory. Besides, my mind was somewhere else: it was in the classroom that I left that morning; it was in the goodbye party that my students prepared for me; and it was in the uncertain future that was ahead of me. -

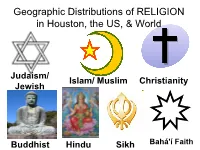

Geographic Distributions of RELIGION in Houston, the US, & World

Geographic Distributions of RELIGION in Houston, the US, & World Judaism/ Islam/ Muslim Christianity Jewish Buddhist Hindu Sikh Bahá'í Faith Learning Objectives, 109 slides • Overview of religious characteristics • Global and US distribution of religious people; Houston Interfaith Unity Council 3 • General demographic characteristics by religion: income, education 7 • Judaism / Jewish 26 • Islam / Muslims 49 • Hindus 80 • Sikhism 96 • Buddhist 103 Summary of Major Holidays & Celebrations by Religion FLDS Fundamentalist Latter Day Saints polygamy Christianity Christmas, Easter, Lent Buddhist Chinese New Year (lunar calendar) Hindu Holi – festival of colors (youth) Diwali – similar to Christmas Janmashtami – Goddess Lord Krishna (children) Jewish / Judaism Hanukah – similar to Christmas Passover – similar to Easter Rosh Hashanha – Jewish New Year Muslim / Islam Ramadan – month long fast with no food/water in daylight hours EID al Fitr – feast to break the fast Pilgrimage to The Hajj Major Religions of the World Folk Folk Christian Islam Buddhist & Chinese Hindu Christian Judaism Christian (Israel) Christian Sects within Major Religions Orthodox Christian Sunni Buddhist & Chinese Muslim Catholic Judaism (Israel) Orthodox Buddhist & Chinese Sunni Hindu Muslim Shia Muslim Catholic Christian Understanding the distribution of Catholics can help to predict location of the new Pope. Non-Religious % There are many parallels between religion and other social variables, in this case wealth and religiosity. more religious less religious Greater wealth -

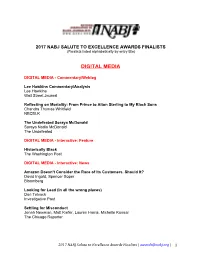

Digital Media

2017 NABJ SALUTE TO EXCELLENCE AWARDS FINALISTS (Finalists listed alphabetically by entry title) DIGITAL MEDIA DIGITAL MEDIA - Commentary/Weblog Lee Hawkins Commentary/Analysis Lee Hawkins Wall Street Journal Reflecting on Mortality: From Prince to Alton Sterling to My Black Sons Chandra Thomas Whitfield NBCBLK The Undefeated Soraya McDonald Soraya Nadia McDonald The Undefeated DIGITAL MEDIA - Interactive: Feature Historically Black The Washington Post DIGITAL MEDIA - Interactive: News Amazon Doesn’t Consider the Race of Its Customers. Should It? David Ingold, Spencer Soper Bloomberg Looking for Lead (in all the wrong places) Dan Telvock Investigative Post Settling for Misconduct Jonah Newman, Matt Kiefer, Lauren Harris, Michelle Kanaar The Chicago Reporter 2017 NABJ Salute to Excellence Awards Finalists | [email protected] | 1 DIGITAL MEDIA > Online Project: Feature The City: Prison's Grip on the Black Family Trymaine Lee NBC News Digital Under Our Skin Staff of The Seattle Times The Seattle Times Unsung Heroes of the Civil Rights Movement Eric Barrow New York Daily News DIGITAL MEDIA > Online Project: News Chicago's disappearing front porch Rosa Flores, Mallory Simon, Madeleine Stix CNN Machine Bias Julia Angwin, Jeff Larson, Surya Mattu, Lauren Kirchner, Terry Parris Jr. ProPublica Nuisance Abatement Sarah Ryley, Barry Paddock, Pia Dangelmayer, Christine Lee ProPublica and The New York Daily News DIGITAL MEDIA > Single Story: Feature Congo's Secret Web of Power Michael Kavanagh, Thomas Wilson, Franz Wild Bloomberg Migration and Separation: -

TEXAS NEWSPAPER COLLECTION the CENTER for AMERICAN HISTORY -A- ABILENE Abilene Daily Reporter (D) MF†*: Feb. 5, 1911; May

TEXAS NEWSPAPER COLLECTION pg. 1 THE CENTER FOR AMERICAN HISTORY rev. 4/17/2019 -A- Abilene Reporter-News (d) MF: [Apr 1952-Aug 31, 1968: incomplete (198 reels)] (Includes Abilene Morning Reporter-News, post- ABILENE 1937) OR: Dec 8, 11, 1941; Jul 19, Dec 13, 1948; Abilene Daily Reporter (d) Jul 21, 1969; Apr 19, 1981 MF†*: Feb. 5, 1911; May 20, 1913; OR Special Editions: Jun. 30, Aug. 19, 1914; Jun. 11, 1916; Sep. 24, 1950; [Jun. 21-Aug. 8, 1918: incomplete]; [vol. 12, no. 1] May 24, 1931 Apr. 8, 1956; (75th Anniversary Ed.) (Microfilm on misc. Abilene reel) [vol. 35, no. 1] (Includes Abilene Morning Reporter-News, pre- Mar. 13, 1966; (85th Anniversary Ed.) 1937, and Sunday Reporter-News - Index available) [vol. 82, no. 1] OR Special Editions: 1931; (50th Anniversary Ed.) Abilene Semi-Weekly Reporter (sw) [vol. 10, no. 1] MF†*: Jun 9, 1914; Jan 8, 1915; Apr 13, 1917 Mar. 15, 1936; (Texas Centennial Ed.) (Microfilm on Misc. Abilene reel) [vol. 1, no. 1] Dec. 6, 1936 Abilene Times (d) [vol. 1, no. 2] MF†: [Mar 5-Jun 1, 1928: incomplete] (Microfilm of Apr 1-Dec 30, 1927 on reel with West Abilene Evening Times (d) Texas Baptist) MF†: Apr 1-Oct 31, 1927 (Microfilm of Mar 5-June 1, 1928 on misc. Abilene- (Microfilm on misc. Abilene reel) Albany reel) OR: Aug 30, Oct 18, 1935 Abilene Morning News (d) OR: Feb 15, 1933 Baptist Tribune (w) MF: [Jan 8, 1903-Apr 18, 1907: incomplete (2 Abilene Morning Reporter (d) reels)] MF†*: Jul 26; Aug 1, 1918 (Microfilm on Misc. -

Texas Civil Rights Trailblazers

Texas Civil Rights Trailblazers 9 Time • Handout 1-1: Complete List of Trailblazers (for teacher use) 3 short sessions (10 minutes per session) and 5 full • Handout 2-1: Sentence Strips, copied, cut, and pasted class periods (50 minutes per period) onto construction paper • Handout 2-2: Categories (for teacher use) Overview • Handout 2-3: Word Triads Discussion Guide (optional), one copy per student This unit is initially phased in with several days of • Handout 3-1: Looping Question Cue Sheet (for teacher use) short interactive activities during a regular unit on • Handout 3-2: Texas Civil Rights Trailblazer Word Search twentieth-Century Texas History. The object of the (optional), one copy per student phasing activities is to give students multiple oppor- • Handout 4-1: Rubric for Research Question, one copy per tunities to hear the names of the Trailblazers and student to begin to become familiar with them and their • Handout 4-2: Think Sheet, one copy per student contributions: when the main activity is undertaken, • Handout 4-3: Trailblazer Keywords (optional), one copy students will have a better perspective on his/her per student Trailblazer within the general setting of Texas in the • Paint masking tape, six markers, and 18 sheets of twentieth century. scrap paper per class • Handout 7-1: Our Texas Civil Rights Trailblazers, one Essential Question copy per every five students • How have courageous Texans extended democracy? • Handout 8-1: Exam on Texas Civil Rights Trailblazers, one copy per student Objectives Activities • Students will become familiar with 32 Texans who advanced civil rights and civil liberties in Texas by Day 1: Mum Human Timeline (10 minutes) examining photographs and brief biographical infor- • Introduce this unit to the students: mation. -

PASADENA INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT Meeting of The

PASADENA INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT Meeting of the Board of Trustees Tuesday, May 27, 2008, at 5:30 P.M. AGENDA The Pasadena Independent School District Board of Trustees Personnel Committee will meet in Room L101 of the Administration Building, 1515 Cherrybrook, Pasadena, Texas on Tuesday, May 27, 2008, at 5:30 P.M. I. Convene in a Quorum and Call to Order; Invocation; Pledge of Allegiance II. Adjournment to closed session pursuant to Texas Government Code Section 551.074 for the purpose of considering the appointment, employment, evaluation, reassignment, duties, discipline or dismissal of a public officer, employee, or to hear complaints or charges against a public officer or employee. III. Reconvene in Open Session IV. Adjourn The Pasadena Independent School District Board of Trustees Policy Committee will meet in the Board Room of the Administration Building, 1515 Cherrybrook, Pasadena, Texas on Tuesday, May 27, 2008, at 5:30 P.M. I. Convene into Open Session II. Discussion regarding proposed policies III. Adjourn The Board of Trustees of the Pasadena Independent School District will meet in regular session at the conclusion of any committee meetings on Tuesday, May 27, 2008, in the Board Room of the Administration Building, 1515 Cherrybrook, Pasadena, Texas. A copy of items on the agenda is attached. I. Convene in a Quorum and Call to Order THE SUBJECTS TO BE DISCUSSED OR CONSIDERED OR UPON WHICH ANY FORMAL ACTION MIGHT BE TAKEN ARE AS FOLLOWS: II. First Order of Business Section II 1. Adjournment to closed session pursuant to