A History of the Perkins School of Theology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Recommended publications

-

Record of Remembrance 377 Record of Remembrance the Record of Remembrance

Called to Serve, Set Apart in Truth, Sent in Love Oklahoma Annual Conference 2007 Journal Disciples: S ECTION J RECORD OF REMEMBRANCE 377 Record of Remembrance The Record of Remembrance CLERGY MARCUS KERRY BARNETT LESTER LEE BOTTOMS PAUL DOUGLAS BOWLES CECIL DENE BROWN OTTO ELLING JR. RICHARD HOWELL FOX JOHN HENRY KAPP HORACE M. MUDD ALBERT PEAK HOWARD W. ROBERTS WILLIAM GORDON SPENCER JOHN CHESTER STOW CLERGY SPOUSES GAIL E. BARBER SUSAN J. BROWN EDNA MAE BYERLY MARY C. CLAY BILLIE J. COOK SUE SMITH DIEL RALPH L. GOOD EDITH M. GROSE RUTH E. GRUBB MAURINE L. MURRAY FRANCES W. POLSON CORA GLADYS POWELL VERDDIE M. SHANNON ELLA M. SIFFORD HAZEL B. STEEL BOBBIE C. WATKINS PAULINE R. WILLIAMS 378 Record of Remembrance CLERGY MARCUS KERRY BARNETT Rev. Marcus Kerry Barnett, 68, of McAlester died Dec. 13, 2006. Marcus Kerry was born Aug. 13, 1938, in Chambers, Okla., to M.K. and Minnie C. Grubbs Barnett. He married Beverly Elaine Ingram on April 20, 1956. He served in the U.S. Army 1957-1964. He worked 15 years as a journeyman lineman for El Paso Electric Co. He graduated from New Mexico State University and Perkins School of Theology. Rev. Barnett was ordained as an elder in 1985. He retired in 2001 after 30 years as a United Methodist pastor. In Oklahoma Conference, he served Atoka, Wewoka-First, Cromwell, Sallisaw, Piedmont, and Poteau. He also served churches in New Mexico Conference. He coached little league teams and was active in civic clubs. He was a Mason, serving in every appointive and elected office. -

The Founding and Defining of a University

An Occasional Paper Number 21 2007 The Founding and Defining of a University By: Marshall Terry The Founding and Defining of a University PREFACE Southern Methodist University (SMU) was founded for a distinct purpose, to serve as the “connectional institution” for the Methodist Church west of the Mississippi when Vanderbilt University gave up its Church connection and that function. Fortunately for the new university, the Church was in the strong Wesleyan tradition of “think and let think” and its founding president Robert Stewart Hyer was a physicist and knowledgeable academic who said at the outset, in 1916, “Religious denominations may properly establish institutions of higher learning, but any institution which is dedicated to the perpetuation of a narrow, sectarian point of view falls far short of the standard of higher learning.” So, founded as a university with a theology school to train ministers and a tiny music school, SMU, while cherishing the spiritual and moral values and traditions of the Church, was by design denominational and not sectarian. Through the years this openness to various ideas and truth claims has led to SMU’s firm educational basis in the liberal arts. In this essay I will consider the character of the founding president, Robert S. Hyer, and of the defining president Willis McDonald Tate; and look at the definition of the University that emerged from Tate’s 1962-1963 Master Plan; and finally assess some of the University’s successes and failures to act according to its stated principles along the way to the present. HYER Who was this founding president and what were the attributes that allowed him to found and lead a new university of limited financial means compared with other new private universities such as Chicago and Stanford? Hyer was a native of Georgia and graduate of Emory College. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries 2017 Turning Towards Zion: An Analysis of the Development of Attitudes Towards Israel of American Reform Jews in the Wake of Israel's War of 1967 Through Examination of the Yearbooks of the Central Conference of American Rabbis Micah Roberts Friedman Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF RELIGION TURNING TOWARDS ZION: AN ANALYSIS OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF ATTITUDES TOWARDS ISRAEL OF AMERICAN REFORM JEWS IN THE WAKE OF ISRAEL’S WAR OF 1967 THROUGH EXAMINATION OF THE YEARBOOKS OF THE CENTRAL CONFERENCE OF AMERICAN RABBIS By MICAH ROBERTS FRIEDMAN A Thesis submitted to the Department of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements of graduation with Honors in the Major 1 2 Table of Contents Signature Page……………………………………………………………………………………...2 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………..4 Chapter One: Before the War 1965 – 1966………………………………………………………..10 1965: Cincinnati, Ohio…………………………………………………………………….10 1966: Toronto, Canada……………………………………………………………………15 Chapter Two: War and its Aftermath 1967 – 1969………………………………………………...18 1967: Los Angeles, California……………………………………………………………...18 1968: Boston, Massachusetts……………………………………………………………....24 1969: Houston, Texas……………………………………………………………………..30 Chapter Three: To Jerusalem and back 1970 – 1973………………………………………………41 1970: Jerusalem, Israel…………………………………………………………………….41 1971: St. Louis, Missouri…………………………………………………………………..49 1972: Grossinger, New York……………………………………………………………....57 -

SMU Interior Pest Control Schedule

SMU Interior Pest Control Schedule Building Name Monthly Semi-monthly Main Campus Residence Halls, Greek Houses, and Apartments A. Frank Smith Hall X Alpha Epsilon Pi X Alpha Psi Lambda - Multicultural Greek Council House X Apartments #1 - Daniel II X Apartments #2 (Daniel House) X Apartments #4 X Apartments #5 X Apartments #6 - Hillcrest Manor X Armstrong Commons X Beta Theta Pi X Boaz Hall X Cockrell-McIntosh Hall X Crum Commons X Kappa Alpha Order X Kappa Sigma X Kathy Crow Commons X Loyd Commons X Mary Randle Hay Hall X McElvaney Hall X Moore Hall X Morrison-McGinnis Hall X Service House X Shuttles Hall X Sigma Alpha Epsilon X Sigma Phi Epsilon X Peyton Hall X Phi Delta Theta X Phi Gamma Delta X Pi Kappa Alpha X Virginia-Snider Hall X Ware Commons X Main Campus Academic, Office, and Athletics Facilities Annette Caldwell Simmons Hall X Barr Memorial Pool X Blanton Student Observatory X Bridwell Library X Carr Collins, Jr. Hall X Caruth Hall X Cary M. Maguire Building X Clements Hall X Crum Basketball Center X Crum Lacrosse and Sports Field - Building X Dallas Hall X Dawson Service Center X Dedman Center for Lifetime Sports and Mustang Band Hall X Dedman Life Sciences Building X Dr. Bob Smith Health Center X Elizabeth Perkins Prothro Hall X Eugene B. Hawk Hall X Fondren Library Center X Fondren Science Building X Fred F. Florence Hall X Gerald J. Ford Stadium - Building X Greer Garson Theatre X Harold Clark Simmons Hall X Hughes-Trigg Student Center X Hyer Hall of Physics X J. -

"And So We Moved Quietly": Southern Methodist University and Desegregation, 1950-1970 Scott A

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2013 "And So We Moved Quietly": Southern Methodist University and Desegregation, 1950-1970 Scott A. Cashion University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Cashion, Scott A., ""And So We Moved Quietly": Southern Methodist University and Desegregation, 1950-1970" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 739. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/739 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. “AND SO WE MOVED QUIETLY”: SOUTHERN METHODIST UNIVERSITY AND DESEGREGATION, 1950-1970 “AND SO WE MOVED QUIETLY”: SOUTHERN METHODIST UNIVERSITY AND DESEGREGATION, 1950-1970 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Scott Alan Cashion Hendrix College Bachelor of Arts in History, 2002 University of Arkansas Master of Arts in History, 2006 May 2013 University of Arkansas ABSTRACT Southern Methodist University was the first Methodist institution in the South to open its doors to African Americans in the early 1950s. There were several factors that contributed to SMU pushing for desegregation when it did. When SMU started the process of desegregation in the fall of 1950, two schools in the Southwest Conference had already admitted at least one black graduate student. University officials, namely then President Umphrey Lee, realized that because other schools had desegregated, it would not be long before SMU would have to do the same. -

Today We Salute Our Graduates

Today we salute our graduates, who stand ready to take the next steps into the future. And we honor the students, faculty, staff, parents and friends who shaped SMU’s first 100 years and laid the foundation for an extraordinary second century. 00086-Program.indd 1 12/11/17 7:16 AM ORDER OF EXERCISE CARILLON CONCERT SPECIAL MUSIC Quarter Past Nine in the Morning “SMU Forever” David Y. Son, Carillonneur Jimmy Dunne Fondren Science Tower Imperial Brass Performed by Clifton Forbis WELCOME CONFERRING OF DEGREES IN COURSE Kevin Paul Hofeditz, Ceremony Marshal Please refrain from applause until all candidates have been presented. PRELUDIAL CONCERT AND FANFARES Marc P. Christensen, Dean of Lyle School of Engineering Jennifer M. Collins, Dean of Dedman School of Law Imperial Brass Thomas DiPiero, Dean of Dedman College of Humanities and Sciences Craig C. Hill, Dean of Perkins School of Theology ACADEMIC PROCESSIONAL Samuel S. Holland, Dean of Meadows School of the Arts The audience remains seated during the academic processional and recessional Stephanie L. Knight, Dean of Annette Caldwell Simmons School of Education and Human Development Thomas B. Fomby, Presiding Chief Marshal Matthew B. Myers, Dean of Cox School of Business Joseph F. Kobylka, Platform Marshal James E. Quick, Associate Vice President for Research and Dean of Thomas W. Tunks, Marshal Lector Graduate Studies Candidates for Graduation A SSISTING : Representatives of the Faculties John A. Hall ’71, ’73, ’79, Executive Director of Enrollment Services and The Platform Party University Registrar Joe Papari ’81, Director of Enrollment Services for Student Systems and CALL TO ORDER Technology Steven C. -

Hyer, Dr. Robert, House 01/14/1986

NPS Form 10-900-* OMB No. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form Continuation sheet Item number all Page 14 TEXAS HISTORIC SITES INVENTORY FORM-TEXAS HISTORICAL COMMISSION (rev.8-82) Williamson 1. County _ 5. USGS Quad No _ 3097-313 Site Nn 632, Phntn City/Rural Georgetown" GE UTM Sectf^r 627-3389 Dr. Robert Hyer House 2. Name 6. Date: Factual Est. 1880 Address _ "ffsF 7. Architect/Builder Contractor 3. Owner . Manuel L. Ramon, Rt. 1, Box 3AAfi Style/Type vernacular Address. Jarrell, Texas 76537 9 Original Use residential 4. Block/Lot _Glasscock/Blk . 27/Lot 2 present Use residential 10 De.'icription One-Story wood-frame dwelling with central-hall plan; exterior walls with weatherboard siding; gable roof with corrugated metal; front elevation faces east; wood sash double-hung windows with 2/2 lights; single-door entrance with two-light transom; one-bay porch with gable roof on east elevation; 11. Present Condition fair—rear additions 12. Signilicance Primary area of significance: architecture and association with a prominent individual. A good example of a late nineteenth-century vernacular^ dwelling. Few alterations. According to tax rolls, property owned by 13. Relationshi lie: Moved Date or Original Site x (aescnhe) residential neighborhood eas CBD; mostly turn-of-the-century dwellings nearby; across from grounds 14 Rihiiography, "^^^ rolls, Sanborn Maps, 15 informant #13> of old Georgetown High School Scarbrough, pg. 238, 248, 388-89^ 16. Recorder D. Moore/HHM Date July 198A DESIGNATIONS PHOTO DATA TNRIS No. -

Transactional Analysis in Psychotherapy

TThhee BBooookk ooff EEvvaann:: TThhee wwoorrkk aanndd lliiffee ooff EEvvaann MMccAArraa SShheerrrraarrdd Keith Tudor | Editor E-book edition The Book of Evan: The work and life of Evan McAra Sherrard Editor: Keith Tudor E-book (2020) ISBN: 9781877431–88-3 Printed edition (2017) ISBN: 9781877431-78-4 © Keith Tudor 2017, 2020 Keith Tudor asserts his moral right to be known as the Editor of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electrical, mechanical, photocopying, recording, digital or otherwise without the prior written permission of Resource Books Ltd. Waimauku, Auckland, New Zealand [email protected] | www.resourcebooks.co.nz Contents The Book of Evan: The work and life of Evan McAra Sherrard Keith Tudor | Editor Contents Foreword. Isabelle Sherrard Poroporoaki: A bridge between two worlds. Haare Williams Introduction to the e-book edition. Keith Tudor Introduction. Keith Tudor The organisation and structure of the book Acknowledgements References Part I. AGRICULTURE Introduction. Keith Tudor Chapter 1. Papers related to agriculture. Evan M. Sherrard Biology (2008) Film review of The Ground We Won (2015) References Chapter 2. Memories of Evan from Lincoln College and from a farm. Alan Nordmeyer, Robin Plummer, and Colin Wrennall Alan Nordmeyer writes Robin Plummer writes Colin Wrennall writes Part II. MINISTRY Introduction. Keith Tudor Chapter 3. Sermons. Evan M. Sherrard St. Patrick’s Day (1963) Sickness unto death (1965) Good grief (1966) When things get out of hand (1966) Rains or refugees? (1968) Unconscious influence (n.d.) Faithful winners (1998) Epiphany (2006) Colonialism (2008) Jesus and Paul — The consummate political activists (2009) A modern man faces Pentecost (2010) Ash Wednesday (2011) Healing (2011) Killed by a dancing girl (2012) Self-love (2012) Geering and Feuerbach (2014) Chapter 4. -

The Ice Bowl: the Cold Truth About Football's Most Unforgettable Game

SPORTS | FOOTBALL $16.95 GRUVER An insightful, bone-chilling replay of pro football’s greatest game. “ ” The Ice Bowl —Gordon Forbes, pro football editor, USA Today It was so cold... THE DAY OF THE ICE BOWL GAME WAS SO COLD, the referees’ whistles wouldn’t work; so cold, the reporters’ coffee froze in the press booth; so cold, fans built small fires in the concrete and metal stands; so cold, TV cables froze and photographers didn’t dare touch the metal of their equipment; so cold, the game was as much about survival as it was Most Unforgettable Game About Football’s The Cold Truth about skill and strategy. ON NEW YEAR’S EVE, 1967, the Dallas Cowboys and the Green Bay Packers met for a classic NFL championship game, played on a frozen field in sub-zero weather. The “Ice Bowl” challenged every skill of these two great teams. Here’s the whole story, based on dozens of interviews with people who were there—on the field and off—told by author Ed Gruver with passion, suspense, wit, and accuracy. The Ice Bowl also details the history of two legendary coaches, Tom Landry and Vince Lombardi, and the philosophies that made them the fiercest of football rivals. Here, too, are the players’ stories of endurance, drive, and strategy. Gruver puts the reader on the field in a game that ended with a play that surprised even those who executed it. Includes diagrams, photos, game and season statistics, and complete Ice Bowl play-by-play Cheers for The Ice Bowl A hundred myths and misconceptions about the Ice Bowl have been answered. -

Appendix B: City of Dallas Registered Historic Places

Appendix B: City of Dallas Registered Historic Places City of Dallas Historic Properties Ref# Property Name Status Listed Date City Street & Number 05001543 1926 Republic National Bank Listed 1/18/2006 Dallas 1309 Main St. 08000539 4928 Bryan Street Apartments Listed 6/12/2008 Dallas 4928 Bryan Street 14000103 511 Akard Building Listed 3/31/2014 Dallas 511 N. Akard 11000343 Adamson, W.H., High School Listed 6/8/2011 Dallas 201 E. 9th St. 95000330 Alcalde Street--Crockett School Historic District Listed 3/23/1995 Dallas 200--500 Alcalde, 421--421A N. Carroll and 4315 Victor 100003599Ambassador Hotel Listed 4/4/2019 Dallas 1300 S. Ervay 100004371Bella Villa Apartments Listed 9/12/2019 Dallas 5506 Miller Ave. 75001965 Belo, Alfred Horatio, House Listed 10/29/1975 Dallas 2115 Ross Ave. 95000311 Bianchi, Didaco and Ida, House Listed 3/23/1995 Dallas 4503 Reiger Ave. 06000651 Bluitt Sanitarium Listed 7/26/2006 Dallas 2036 Commerce St. 08000658 Bromberg, Alfred and Juanita, House Listed 7/8/2008 Dallas 3201 Wendover Rd. 95000327 Bryan--Peak Commercial Historic District Listed 3/23/1995 Dallas 4214--4311 Bryan Ave. and 1325--1408 N. Peak 08000475 Building at 3525 Turtle Creek Boulevard Listed 5/29/2008 Dallas 3525 Turtle Creek Blvd. 80004489 Busch Building Listed 7/4/1980 Dallas 1501--1509 Main St. 96001015 Busch--Kirby Building (Boundary Increase) Listed 9/12/1996 Dallas 1501--1509 Main St. 100003923Cabana Motor Hotel Listed 5/9/2019 Dallas 899 N. Stemmons Frwy. 91001901 Cedar Springs Place Listed 12/30/1991 Dallas 2531 Lucas Dr. 95000307 Central Congregational Church Listed 3/23/1995 Dallas 1530 N. -

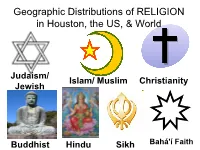

Geographic Distributions of RELIGION in Houston, the US, & World

Geographic Distributions of RELIGION in Houston, the US, & World Judaism/ Islam/ Muslim Christianity Jewish Buddhist Hindu Sikh Bahá'í Faith Learning Objectives, 109 slides • Overview of religious characteristics • Global and US distribution of religious people; Houston Interfaith Unity Council 3 • General demographic characteristics by religion: income, education 7 • Judaism / Jewish 26 • Islam / Muslims 49 • Hindus 80 • Sikhism 96 • Buddhist 103 Summary of Major Holidays & Celebrations by Religion FLDS Fundamentalist Latter Day Saints polygamy Christianity Christmas, Easter, Lent Buddhist Chinese New Year (lunar calendar) Hindu Holi – festival of colors (youth) Diwali – similar to Christmas Janmashtami – Goddess Lord Krishna (children) Jewish / Judaism Hanukah – similar to Christmas Passover – similar to Easter Rosh Hashanha – Jewish New Year Muslim / Islam Ramadan – month long fast with no food/water in daylight hours EID al Fitr – feast to break the fast Pilgrimage to The Hajj Major Religions of the World Folk Folk Christian Islam Buddhist & Chinese Hindu Christian Judaism Christian (Israel) Christian Sects within Major Religions Orthodox Christian Sunni Buddhist & Chinese Muslim Catholic Judaism (Israel) Orthodox Buddhist & Chinese Sunni Hindu Muslim Shia Muslim Catholic Christian Understanding the distribution of Catholics can help to predict location of the new Pope. Non-Religious % There are many parallels between religion and other social variables, in this case wealth and religiosity. more religious less religious Greater wealth -

Telling the Perkins Story in This Issue FALL 2014P Erspective 10 17 32 44

erspective P FALL 2014 | PERKINS SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY Telling the Perkins Story IN ThiS ISSUE FALL 2014P erspective 10 17 32 44 INTRODUCTION REAL EXPERIENCE 3 Letter from the Dean 28 New Center for Preaching Excellence 30 Karis Stahl Fadely Award Recipients Share Their Stories IN PERSPECTIVE 32 Celebration of the Degrees and Academic Achievements 3 My Story, Your Story, Our Story: The Perkins Journey 34–36 Staff News and Retirements 6 Telling the Perkins Story 36 Eric White Receives Fellowship for Gutenberg Bible Research 9 John Martin Named New Development Director 37 Perkins Chapel Named “Best Wedding Ceremony Site” 10 100 Years of Telling the Story 38 Student News 13 The Truth About Story 38 Faith Calls: Theological Programs for Young People 15 Redesigned Website, Social Media Outreach 39 Alumni/ae News 41 HIGHER LEARNING Pastoral Care Certificates Awarded 41 Perkins Hosts 2015 National Festival of Young Preachers 16 Perkins Offers New M.A.M. Degree 41 Islamic Law Expert Lectures at Perkins 17 Bridwell Library Torah Scroll Exhibited at Vatican 42 Perkins Chapel Celebrates Creative Worship 19 Richard P. Heitzenrater Honored 19 Visiting Scholar Dr. Fernando F. Segovia VITAL MINISTRY 20 Slides and Scrolls: Bridwell Library Artifacts 44–46 Distinguished Alumnus, Seals Laity Award 21 John R. Levison Joins Perkins Faculty 47 House-Raising Honors Barry Hughes 22 Philip Wingeier-Rayo Named MAP/COSS Director 47 Meet the Perkins Alumni/ae Recruitment Team 23 Pastoral Care Events Feature Bishop Teresa Snorton 48 Master of Sacred Music News and Events 23–27 Faculty News, Richard Nelson Retires 49 Perkins Awarded Lilly Grant for Student Debt Research 27 Perkins Hosts Institute on Theology and Disability 50 Telling the Story Through Global Engagement 27 Center for Evangelism and Missional Churches 52 Perkins in Singapore 53 Memoriams 53 From the Mailbox Dean: William B.