"And So We Moved Quietly": Southern Methodist University and Desegregation, 1950-1970 Scott A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of the Perkins School of Theology

FROM THE COLLECTIONS OF Bridwell Library PERKINS SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY SOUTHERN METHODIST UNIVERSITY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 http://www.archive.org/details/historyofperkinsOOgrim A History of the Perkins School of Theology A History of the PERKINS SCHOOL of Theology Lewis Howard Grimes Edited by Roger Loyd Southern Methodist University Press Dallas — Copyright © 1993 by Southern Methodist University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America FIRST EDITION, 1 993 Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to: Permissions Southern Methodist University Press Box 415 Dallas, Texas 75275 Unless otherwise credited, photographs are from the archives of the Perkins School of Theology. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Grimes, Lewis Howard, 1915-1989. A history of the Perkins School of Theology / Lewis Howard Grimes, — ist ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-87074-346-5 I. Perkins School of Theology—History. 2. Theological seminaries, Methodist—Texas— Dallas— History. 3. Dallas (Tex.) Church history. I. Loyd, Roger. II. Title. BV4070.P47G75 1993 2 207'. 76428 1 —dc20 92-39891 . 1 Contents Preface Roger Loyd ix Introduction William Richey Hogg xi 1 The Birth of a University 1 2. TheEarly Years: 1910-20 13 3. ANewDean, a New Building: 1920-26 27 4. Controversy and Conflict 39 5. The Kilgore Years: 1926-33 51 6. The Hawk Years: 1933-5 63 7. Building the New Quadrangle: 1944-51 81 8. The Cuninggim Years: 1951-60 91 9. The Quadrangle Comes to Life 105 10. The Quillian Years: 1960-69 125 11. -

The Founding and Defining of a University

An Occasional Paper Number 21 2007 The Founding and Defining of a University By: Marshall Terry The Founding and Defining of a University PREFACE Southern Methodist University (SMU) was founded for a distinct purpose, to serve as the “connectional institution” for the Methodist Church west of the Mississippi when Vanderbilt University gave up its Church connection and that function. Fortunately for the new university, the Church was in the strong Wesleyan tradition of “think and let think” and its founding president Robert Stewart Hyer was a physicist and knowledgeable academic who said at the outset, in 1916, “Religious denominations may properly establish institutions of higher learning, but any institution which is dedicated to the perpetuation of a narrow, sectarian point of view falls far short of the standard of higher learning.” So, founded as a university with a theology school to train ministers and a tiny music school, SMU, while cherishing the spiritual and moral values and traditions of the Church, was by design denominational and not sectarian. Through the years this openness to various ideas and truth claims has led to SMU’s firm educational basis in the liberal arts. In this essay I will consider the character of the founding president, Robert S. Hyer, and of the defining president Willis McDonald Tate; and look at the definition of the University that emerged from Tate’s 1962-1963 Master Plan; and finally assess some of the University’s successes and failures to act according to its stated principles along the way to the present. HYER Who was this founding president and what were the attributes that allowed him to found and lead a new university of limited financial means compared with other new private universities such as Chicago and Stanford? Hyer was a native of Georgia and graduate of Emory College. -

Race and College Football in the Southwest, 1947-1976

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE DESEGREGATING THE LINE OF SCRIMMAGE: RACE AND COLLEGE FOOTBALL IN THE SOUTHWEST, 1947-1976 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By CHRISTOPHER R. DAVIS Norman, Oklahoma 2014 DESEGREGATING THE LINE OF SCRIMMAGE: RACE AND COLLEGE FOOTBALL IN THE SOUTHWEST, 1947-1976 A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY ____________________________ Dr. Stephen H. Norwood, Chair ____________________________ Dr. Robert L. Griswold ____________________________ Dr. Ben Keppel ____________________________ Dr. Paul A. Gilje ____________________________ Dr. Ralph R. Hamerla © Copyright by CHRISTOPHER R. DAVIS 2014 All Rights Reserved. Acknowledgements In many ways, this dissertation represents the culmination of a lifelong passion for both sports and history. One of my most vivid early childhood memories comes from the fall of 1972 when, as a five year-old, I was reading the sports section of one of the Dallas newspapers at my grandparents’ breakfast table. I am not sure how much I comprehended, but one fact leaped clearly from the page—Nebraska had defeated Army by the seemingly incredible score of 77-7. Wild thoughts raced through my young mind. How could one team score so many points? How could they so thoroughly dominate an opponent? Just how bad was this Army outfit? How many touchdowns did it take to score seventy-seven points? I did not realize it at the time, but that was the day when I first understood concretely the concepts of multiplication and division. Nebraska scored eleven touchdowns I calculated (probably with some help from my grandfather) and my love of football and the sports page only grew from there. -

Tcu-Smu Series

FROG HISTORY 2008 TCU FOOTBALL TCU FOOTBALL THROUGH THE AGES 4General TCU is ready to embark upon its 112th year of Horned Frog football. Through all the years, with the ex cep tion of 1900, Purple ballclubs have com pet ed on an or ga nized basis. Even during the war years, as well as through the Great Depres sion, each fall Horned Frog football squads have done bat tle on the gridiron each fall. 4BEGINNINGS The newfangled game of foot ball, created in the East, made a quiet and un offcial ap pear ance on the TCU campus (AddRan College as it was then known and lo cat ed in Waco, Tex as, or nearby Thorp Spring) in the fall of 1896. It was then that sev er al of the col lege’s more ro bust stu dents, along with the en thu si as tic sup port of a cou ple of young “profs,” Addison Clark, Jr., and A.C. Easley, band ed to gether to form a team. Three games were ac tu al ly played that season ... all af ter Thanks giv ing. The first con test was an 86 vic to ry over Toby’s Busi ness College of Waco and the other two games were with the Houston Heavy weights, a town team. By 1897 the new sport had progressed and AddRan enlisted its first coach, Joe J. Field, to direct the team. Field’s ballclub won three games that autumn, including a first victory over Texas A&M. The only loss was to the Univer si ty of Tex as, 1810. -

All-Time All-America Teams

1944 2020 Special thanks to the nation’s Sports Information Directors and the College Football Hall of Fame The All-Time Team • Compiled by Ted Gangi and Josh Yonis FIRST TEAM (11) E 55 Jack Dugger Ohio State 6-3 210 Sr. Canton, Ohio 1944 E 86 Paul Walker Yale 6-3 208 Jr. Oak Park, Ill. T 71 John Ferraro USC 6-4 240 So. Maywood, Calif. HOF T 75 Don Whitmire Navy 5-11 215 Jr. Decatur, Ala. HOF G 96 Bill Hackett Ohio State 5-10 191 Jr. London, Ohio G 63 Joe Stanowicz Army 6-1 215 Sr. Hackettstown, N.J. C 54 Jack Tavener Indiana 6-0 200 Sr. Granville, Ohio HOF B 35 Doc Blanchard Army 6-0 205 So. Bishopville, S.C. HOF B 41 Glenn Davis Army 5-9 170 So. Claremont, Calif. HOF B 55 Bob Fenimore Oklahoma A&M 6-2 188 So. Woodward, Okla. HOF B 22 Les Horvath Ohio State 5-10 167 Sr. Parma, Ohio HOF SECOND TEAM (11) E 74 Frank Bauman Purdue 6-3 209 Sr. Harvey, Ill. E 27 Phil Tinsley Georgia Tech 6-1 198 Sr. Bessemer, Ala. T 77 Milan Lazetich Michigan 6-1 200 So. Anaconda, Mont. T 99 Bill Willis Ohio State 6-2 199 Sr. Columbus, Ohio HOF G 75 Ben Chase Navy 6-1 195 Jr. San Diego, Calif. G 56 Ralph Serpico Illinois 5-7 215 So. Melrose Park, Ill. C 12 Tex Warrington Auburn 6-2 210 Jr. Dover, Del. B 23 Frank Broyles Georgia Tech 6-1 185 Jr. -

1972 Topps Football Checklist

1972 Topps Football Checklist 1 1971 AFC Rushing Leaders (Floyd Little, Larry Csonka, Marv Hubbard) 2 1971 NFC Rushing Leaders (John Brockington, Steve Owens, Willie Ellison) 3 1971 AFC Passing Leaders (Bob Griese, Len Dawson, Virgil Carter) 4 1971 NFC Passing Leaders (Roger Staubach, Greg Landry, Billy Kilmer) 5 1971 AFC Receiving Leaders (Fred Biletnikoff, Otis Taylor, Randy Vataha) 6 1971 NFC Receiving Leaders (Bob Tucker, Ted Kwalick, Harold Jackson, Roy Jefferson) 7 1971 AFC Scoring Leaders (Garo Yepremian, Jan Stenerud, Jim O'Brien) 8 1971 NFC Scoring Leaders (Curt Knight, Errol Mann, Bruce Gossett) 9 Jim Kiick 10 Otis Taylor 11 Bobby Joe Green 12 Ken Ellis 13 John Riggins RC 14 Dave Parks 15 John Hadl 16 Ron Hornsby 17 Chip Myers RC 18 Billy Kilmer 19 Fred Hoaglin 20 Carl Eller 21 Steve Zabel 22 Vic Washington RC 23 Len St. Jean 24 Bill Thompson 25 Steve Owens RC 26 Ken Burrough RC 27 Mike Clark 28 Willie Brown 29 Checklist 30 Marlin Briscoe RC 31 Jerry Logan 32 Donny Anderson 33 Rich McGeorge 34 Charlie Durkee 35 Willie Lanier 36 Chris Farasopoulos 37 Ron Shanklin RC 38 Forrest Blue RC 39 Ken Reaves 40 Roman Gabriel 41 Mac Percival 42 Lem Barney 43 Nick Buoniconti Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 44 Charlie Gogolak 45 Bill Bradley RC 46 Joe Jones 47 Dave Williams 48 Pete Athas 49 Virgil Carter 50 Floyd Little 51 Curt Knight 52 Bobby Maples 53 Charlie West 54 Marv Hubbard RC 55 Archie Manning RC 56 Jim O'Brien RC 57 Wayne Patrick 58 Ken Bowman 59 Roger Wehrli 60 Charlie Sanders 61 Jan Stenerud 62 Willie Ellison 63 -

An Inventory of the Merrimon Cuninggim Papers

An Inventory of the Merrimon Cuninggim papers Revised May 5, 2017 [work in progress] Title: Merrimon Cuninggim papers Merrimon Cuninggim (1911–1995) was a Methodist minister and educator who served as Dean of Perkins School of Theology, Southern Methodist University, from 1951 until 1960. Date range: 1943-1993 Bulk date range: 1951-1960 Extent: 16 boxes (16 linear feet) [Boxes 15-31] Collection BridArch 1.006 Acquired. The folder-level inventory that follows describes the collection before processing. Box File Contents 15 01 A – General 02 Abingdon 03 Abingdon – Emory S. Buck, 1956-1960 04 Adkins, Carl 05 Admission of Vanderbilt St., 1960 06 Ahmad-Shah, E. 07 Akin, Dr. Nita 08 Allen, Yorke 09-14 Alumni Association, 1953-1960 15 American Airlines 16 American Association of C. for T. Ed., 1953-1954 17-24 American Association of Theological Schools, 1951-1960 25-37 American Association of Theological Schools – Commission on Accrediting, 1954-1959 38-41 American Association of Theological Schools – Faculty Fellowship Commission, 1956- 1960 Bridwell Library * Perkins School of Theology * Southern Methodist University 1 42 American Association of Theological Schools – Guides for Self-Study 43-45 American Association of Theological Schools – Lilly Foundation, 1956-1959 46 American Association of Theological Schools – Motives in Christian Service, 1957 47 American Association of Theological Schools – Procedure in Re-inspection, 1958-1959 48 American Association of Theological Schools – Report, 1956 49-50 American Association of Theological Schools – Senior Scholarship Awards, 1958-1960 51 American Association of University Professors 52 American Council on Education 53 American Foundation Information Service 54 American Jewish Committee 55 Anderson, Bernard 56 Anderson, Thomas J., 1952 57 Applications for Positions, 1951-1952 58-59 Appointments – Reappointments, 1954-1956 60 Arnott, Robert J. -

THE HISTORY of SMU FOOTBALL 1910S on the Morning of Sept

OUTLOOK PLAYERS COACHES OPPONENTS REVIEW RECORDS HISTORY MEDIA THE HISTORY OF SMU FOOTBALL 1910s On the morning of Sept. 14, 1915, coach Ray Morrison held his first practice, thus marking the birth of the SMU football program. Morrison came to the school in June of 1915 when he became the coach of the University’s football, basketball, baseball and track teams, as well as an instructor of mathematics. A former All-Southern quarterback at Vanderbilt, Morrison immediately installed the passing game at SMU. A local sportswriter nicknamed the team “the Parsons” because the squad was composed primarily of theology students. SMU was a member of the Texas Intercollegiate Athletic Association, which ruled that neither graduate nor transfer students were eligible to play. Therefore, the first SMU team consisted entirely of freshmen. The Mustangs played their first game Oct. 10, 1915, dropping a 43-0 decision to TCU in Fort Worth. SMU bounced back in its next game, its first at home, to defeat Hendrix College, 13-2. Morrison came to be known as “the father of the forward pass” because of his use of the passing game on first and second downs instead of as a last resort. • During the 1915 season, the Mustangs posted a record of 2-5 and scored just three touchdowns while giving up 131 Ownby Stadium was built in 1926 points. SMU recorded the first shutout in school history with a 7-0 victory over Dallas University that year. • SMU finished the 1916 season 0-8-2 and suffered its worst 1920s 1930s loss ever, a 146-3 drubbing by Rice. -

BIG 33 Game History

1958-2015 BIG 33 Game History June 19, 2015 Pennsylvania’s next score. Toledo-bound tailback Terry June 16, 2012 58th Big 33 Football Classic Swanson made the turnover count as he punched in 55th Big 33 Football Classic Maryland 3 – Pennsylvania 20 a touchdown from 5 yards out. That made it a 24-14 Ohio 24 - Pennsylvania 21 Maryland lead with 4:23 to go in the third quarter. Pyles led Pennsylvania’s first drive of the fourth Six costly Pennsylvania turnovers It didn’t take Pennsylvania’s all- quarter and capitalized with a 20-yard touchdown run ultimately undid an outstanding star squad long to jump out to an to make it just a three-point deficit. The Pennsylvania defensive performance from the early lead, as South Fayette’s Brett defense took over after that, riding the momentum. The Keystone side, setting the stage Brumbaugh found Harrisburg’s defensive line swarmed into the Maryland backfield for Ohio kicker Tyler Grassman’s Amechie Walker on a deep slant between the hash and held them to negative 3 yards of offense in the 39-yard field goal that lifted Ohio to a stunning 24-21 marks. One play. One pass. 63 yards, six points and fourth quarter. Lower Dauphin kicker Joe Julius, who overtime victory. The outcome was especially painful barely 13 seconds off the clock. erased a disastrous start, nailed a 29-yard field goal that for Pennsylvania because of a 14-point fourth quarter Urbana’s Ray Grey started the game for Maryland at forged a 24-all battle with 1:19 left in regulation. -

THE SKIFF * Pag

estiva! Play Opens onight; Recitals ill Start Tuesday HV DAI I EDMONDS ,.. :, bant oi Yonkers," the Fim dramatii :i open at I p.m. today In the Littli Xhi I 11 «d l'"V(' by Thornton Wilder, also v.ii; u ,,,, • and Tuesday through Saturday ol next week, \ program <>f M—art piano I—tai will begin next week'a jtival musical prtaeatatieai at 1:19 a m Tuesdaj in Ed Lantlrcth Hitorium • i be featured are sonatas in A major, C major, f majoi and Fantasia. Pianists will be Misses Billie Li tie. ' Jan —Skiff Phut.. I» IIHRI KS DOWH I. Qji] Wllllama, Mary White and Harns Cavender. "OOll. MS. HACKL," gurgles Mrs. Mary Lynn Brush, second from ram of Mozart and Schumann vocal and pia no works will right, as she tickles.. the chin of Cornelius Hack! <Dennis Brutoni. Miss : at 8:15 p_m. Wednesday--j ...In —Ed ..Landrethu,,v..>i, Voice students Barbara Jones, left and Miss Carlene Waters, react differently. All ll perform are Miss ( arol ( almea, Jack Vandagriff, Miss Elaine appear in "The Merchant of Yonkers v! IcnMcClaskej opening tonight. Lalsti »1H * ■*»" Su' „„ ,s, rerl] "«■ viI. unit jnd Jo.in llainlrr. America Is .,1 H 15 p in in ia itudenti im ,,t Schu rkj Mlsa K.iy Like Child, Henricha, Miss I ,i. Eliza will plaj Merchant ol Says Bash Bobby Pal America is an adolescent na- ion, Kiln.olid tion lacking in emotional and ■ Creson, political security, Dr. Lawrence :i. nnls Bru Bash, minister of University I - tralgi au Christian Church of Austin I and Mrs and mam speaker for Religious isti Emphasis Week, sod Wed H MISS Barbara laatca, da] ll„nv Sol in. -

2004 Cingular/ABC Sports All-America Program

EXCESSIVE CELEBRATION AWARDS CEREMONY & BANQUET Friday, December 10, 2004 Disney-MGM Studios WELCOME December 10, 2004 Players, Members, Sponsors and Guests: Welcome to the 2004 Football Writers Association of America We view this evening as a celebration of the good work (FWAA) All-America Team Celebration. Tonight’s event was accomplished by the Foundation throughout the past year made possible through the generous contributions of ABC and for the many outstanding people who have devoted their Sports and Cingular along with many of our good friends considerable time and talents to make Florida Citrus Sports throughout the community. To those who donated goods, Foundation what it is today. We salute those individuals, services, time or financial resources, we say thank you. Your particularly our past presidents, as we gather to honor the generosity will allow us to make a substantial contribution finest collegiate football players in the land. The All-America to the Florida Citrus Sports Foundation, which benefits players with us tonight have performed at a level to which economically disadvantaged youth in the Central Florida we all aspire – these young men are simply the best! community. We also greatly appreciate the cooperation and The long hours on the practice field, the tireless effort in support we have received from FWAA President Dick Weiss the weight room, hours in the classroom and the dedication and Executive Director Steve Richardson. and unwavering commitment to their respective teams and to the sport of football have earned them a deserved position on center stage. We marvel at their talents but more importantly congratulate them on their wonderful accomplishments. -

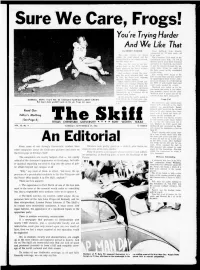

An Editorial

Sure We Care, Frogs! You're Trying Harder And We Like That By BENNY HUDSON I-1" halfback, Jim Kauver, scampered fur '.n total yards, all The rains stopped, the crowd to no .1 i ill cane, the ban I played and the The Floridians' first mark on the Fro is the crowd cheered, scoreboard came with I 17 left in but the Fro ' Ic t the first period when their field goal Thi-. was thi torj of last .v<! specialist, Les Murdock, was forced unlay night a the TCU student to put the pigskin through the up- bod> uppoi ti d the r i ig : in theii rights twice before he could get second outin ; of the year the three points nn the scoreboard And ' around the can for his team The seiinn;: drive began at the I HI-, this week indicated that, win 01 lose, the Frogs were enjoying FSU 33 yard strip*- and was sparked ma ive tudent backing by quarterback Steve Teasi's three After suffering their second con i a • in to plays to set the ball on the TVU 17 with fourth ifown ami si cutivc nt< ■ i1 tional etback, the eiejit yards needed for a first Tt '1 Horned Frogs will open con ference play Saturday afternoon Murdock was called in for the placement and made it, but offset in * the i fniversity of Arkan a tine, penalties wiped out the play Razorb ick • in a televi ted till at Murdock tried it again and the 33 Anion Carter Stadium yard kick *as once a^ain good In l.i i Saturday night's action at DARRELL MOTT, TCU'S NO.