Fan-Shaped Spectrums of Species and Paleopolyploidy for Crossbreeding Evolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Checklist of Fish and Invertebrates Listed in the CITES Appendices

JOINTS NATURE \=^ CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Checklist of fish and mvertebrates Usted in the CITES appendices JNCC REPORT (SSN0963-«OStl JOINT NATURE CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Report distribution Report Number: No. 238 Contract Number/JNCC project number: F7 1-12-332 Date received: 9 June 1995 Report tide: Checklist of fish and invertebrates listed in the CITES appendices Contract tide: Revised Checklists of CITES species database Contractor: World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CB3 ODL Comments: A further fish and invertebrate edition in the Checklist series begun by NCC in 1979, revised and brought up to date with current CITES listings Restrictions: Distribution: JNCC report collection 2 copies Nature Conservancy Council for England, HQ, Library 1 copy Scottish Natural Heritage, HQ, Library 1 copy Countryside Council for Wales, HQ, Library 1 copy A T Smail, Copyright Libraries Agent, 100 Euston Road, London, NWl 2HQ 5 copies British Library, Legal Deposit Office, Boston Spa, Wetherby, West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ 1 copy Chadwick-Healey Ltd, Cambridge Place, Cambridge, CB2 INR 1 copy BIOSIS UK, Garforth House, 54 Michlegate, York, YOl ILF 1 copy CITES Management and Scientific Authorities of EC Member States total 30 copies CITES Authorities, UK Dependencies total 13 copies CITES Secretariat 5 copies CITES Animals Committee chairman 1 copy European Commission DG Xl/D/2 1 copy World Conservation Monitoring Centre 20 copies TRAFFIC International 5 copies Animal Quarantine Station, Heathrow 1 copy Department of the Environment (GWD) 5 copies Foreign & Commonwealth Office (ESED) 1 copy HM Customs & Excise 3 copies M Bradley Taylor (ACPO) 1 copy ^\(\\ Joint Nature Conservation Committee Report No. -

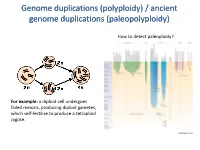

Polyploidy) / Ancient Genome Duplications (Paleopolyploidy

Genome duplications (polyploidy) / ancient genome duplications (paleopolyploidy) How to detect paleoploidy? For example: a diploid cell undergoes failed meiosis, producing diploid gametes, which self-fertilize to produce a tetraploid zygote. Timing of duplication by trees (phylogenetic timing) Phylogenetic timing of duplicates b Paramecium genome duplications Comparison of two scaffolds originating from a common ancestor at the recent WGD Saccharomyces cerevisiae Just before genome duplication Just after genome duplication More time after genome duplication Unaligned view (removing gaps just like in cerev has occurred) Saccharomyces cerevisiae Problem reciprocal gene loss (extreme case); how to solve? Problem reciprocal gene loss (extreme case); how to solve? Just before genome duplication Outgroup! Just after genome duplication Outgroup Just after genome duplication Outgroup More time after genome duplication Outgroup Problem (extreme case); how to solve? Outgroup Outgroup Outgroup Outgroup Outgroup Using other genomes Wong et al. 2002 PNAS Centromeres Vertebrate genome duplication Nature. 2011 Apr 10. [Epub ahead of print] Ancestral polyploidy in seed plants and angiosperms. Jiao Y, Wickett NJ, Ayyampalayam S, Chanderbali AS, Landherr L, Ralph PE, Tomsho LP, Hu Y, Liang H, Soltis PS, Soltis DE, Clifton SW, Schlarbaum SE, Schuster SC, Ma H, Leebens-Mack J, Depamphilis CW. Flowering plants Flowering MOSS Vertebrates Teleosts S. serevisiae and close relatives Paramecium Reconstructed map of genome duplications allows unprecedented mapping -

A 'David and Goliath'

Current Genomics, 2002, 3, 563-576 563 Nucleolar Dominance: A ‘David and Goliath’ Chromatin Imprinting Process W. Viegas1,*, N. Neves1,2, M. Silva1, A. Caperta1,2, and L. Morais-Cecílio1 1Centro de Botânica Aplicada à Agricultura, Secção de Genética/DBEB, Instituto Superior de Agronomia, 1349-017 Lisboa, 2Departamento de Ciências Biológicas e Naturais, Universidade Lusófona de Humanidades e Tecnologias, Campo Grande 376, 1749-042 Lisboa, Portugal Abstract: Nucleolar dominance is an enigma. The puzzle of differential amphiplasty has remained unresolved since it was first recognised and described in Crepis hybrids by Navashin in 1934. Here we review the body of knowledge that has grown out of the many models that have tried to find the genetic basis for differential rRNA gene expression in hybrids, and present a new interpretation. We propose and discuss a chromatin imprinting model which re-interprets differential amphiplasty in terms of two genomes of differing size occupying a common space within the nucleus, and with heterochromatin as a key player in the scenario. Difference in size between two parental genomes induces an inherited epigenetic mark in the hybrid that allows patterns of chromatin organization to have positional effects on the neighbouring domains. This chromatin imprinting model can be also used to explain complex genomic interactions which transcend nucleolar dominance and which can account for the overall characteristics of hybrids. Gene expression in hybrids, relative to parentage, is seen as being based on the nuclear location of the sequences concerned within their genomic environment, and where the presence of particular repetitive DNA sequences are ‘sensed’, and render silent the adjacent information. -

Gene Loss and Adaptation in Saccharomyces Genomes

Genetics: Published Articles Ahead of Print, published on December 1, 2005 as 10.1534/genetics.105.048900 After the duplication: gene loss and adaptation in Saccharomyces genomes Paul F. Cliften*,1, Robert S. Fulton§, Richard K. Wilson*, §, and Mark Johnston* *Department of Genetics and §Genome Sequencing Center, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 South Euclid Ave., St. Louis, MO, 63110; 1Current address: Department of Biology, Utah State University, 5305 Old Main Hill, Logan, UT, 84322 Running head: Saccharomyces genomic duplications Key words: genomic duplication, comparative sequence analysis, Saccharomyces phylogeny, yeast Corresponding author: Mark Johnston Department of Genetics Campus Box 8232 Washington University Medical School 4566 Scott Ave. St. Louis, MO 63110 TEL: 314-362-2735 FAX: 314-362-2157 [email protected] ABSTRACT The ancient duplication of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome and subsequent massive loss of duplicated genes is apparent when it is compared to the genomes of related species that diverged before the duplication event. To learn more about the evolutionary effects of the duplication event, we compared the S. cerevisiae genome to other Saccharomyces genomes. We demonstrate that the whole genome duplication occurred before S. castellii diverged from S. cerevisiae. In addition to more accurately dating the duplication event, this finding allowed us to study the effects of the duplication on two separate lineages. Analyses of the duplication regions of the genomes indicate that most of the duplicated genes (approximately 85%) were lost before the speciation. Only a small amount of paralogous gene loss (4-6%) occurred after speciation. On the other hand, S. castellii appears to have lost several hundred genes that were not retained as duplicated paralogs. -

Iv Gene Duplication and the Evolution of Silenced

Gene Duplication and the Evolution of Silenced Chromatin in Yeasts by Meleah A. Hickman University Program in Genetics and Genomics Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Laura Rusche, Advisor ___________________________ Paul Magwene, Chair ___________________________ Fred Dietrich ___________________________ Joe Heitman ___________________________ Beth Sullivan Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University Program in Genetics and Genomics in the Graduate School of Duke University 2010 i v ABSTRACT Gene Duplication and the Evolution of Silenced Chromatin in Yeasts by Meleah A. Hickman University Program in Genetics and Genomics Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Laura Rusche, Advisor ___________________________ Paul Magwene, Chair ___________________________ Fred Dietrich ___________________________ Joe Heitman ___________________________ Beth Sullivan An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University Program in Genetics and Genomics in the Graduate School of Duke University 2010 Copyright by Meleah A. Hickman 2010 Abstract In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, proper maintenance of haploid cell identity requires the SIR complex to mediate the silenced chromatin found at the cryptic mating-type loci, HML and HMR. This complex consists of Sir2, a histone deacetylase, and the histone binding proteins Sir3 and Sir4. Interestingly, both Sir2 and Sir3 have paralogs from a genome duplication that occurred after the divergence of Saccharomyces and Kluyveromyces species, approximately 100 million years ago. The histone deacetylase HST1 is the paralog of SIR2 and works with the promoter-specific SUM1 complex to repress sporulation and alpha-specific genes. ORC1 is the paralog of SIR3 and is an essential subunit of the Origin Recognition Complex and also recruits SIR proteins to the HM loci. -

Whole-Genome Duplications and Paleopolyploidy Whole-Genome Duplications

Whole-genome duplications and paleopolyploidy Whole-genome duplications AUTOPOLYPLOIDY ALLOPOLYPLOIDY Hegarty and HiscockHegarty 2008, 18 Current Biology Examples of allopolyploid speciation Hegarty and Hiscock 2008, Current Biology 18 Whole-genome duplications of different age time neopolyploidy mesopolyploidy paleopolyploidy time Whole-genome duplications in protozoa •Aury et al. (2006) analyzed the unicellular eukaryote Paramecium tetraurelia • most of 40,000 genes arose through at least 3 successive whole-genome duplications (WGDs) • most recent duplication most likely caused an explosion of speciation events that gave rise to the P. aurelia complex (15 sibling species) • some genes have been lost, some retained • many retained (duplicated) genes do not generate functional innovations but are important because of the gene dosage effect Whole-genome duplications in yeast • genome comparison between two yeast species, Saccharomyces cerevisiae (n=16) and Kluyveromyces waltii (n=8) • each region of K. waltii corresponding to two regions of S. cerevisiae •the S. cerevisiae genome underwent a WGD after the two yeast species diverged • in nearly every case (95%), accelerated evolution was confined to only one of the two paralogues (= one of the paralogues retained an ancestral function, the other was free to evolve more rapidly and acquired a derived function) Kellis et al. 2004, Nature 428 Whole-genome duplications in yeast Kellis et al. 2004, Nature 428 a) after divergence from K. waltii, the Saccharomyces lineage underwent a genome duplication event (2 copies of every gene and chromosome) b) duplicated genes were mutated and some lost c) two copies kept for only a small minority of duplicated genes d) the conserved order of duplicated genes (nos. -

Transposable Elements in Polyploid Evolution Final.Pdf

Transposable elements and polyploid evolution in animals Fernando Rodriguez and Irina R. Arkhipova Address Josephine Bay Paul Center for Comparative Molecular Biology and Evolution, Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, MA 02543, USA Corresponding author: Arkhipova, Irina R. ([email protected]) Polyploidy in animals is much less common than in plants, where it is thought to be pervasive in all higher plant lineages. Recent studies have highlighted the impact of polyploidization and the associated process of diploidy restoration on the evolution and speciation of selected taxonomic groups in the animal kingdom: from vertebrates represented by salmonid fishes and African clawed frogs to invertebrates represented by parasitic root-knot nematodes and bdelloid rotifers. In this review, we focus on the unique and diverse roles that transposable elements may play in these processes, from marking and diversifying subgenome-specific chromosome sets prior to hybridization, to influencing genome restructuring during rediploidization, to affecting subgenome-specific regulatory evolution, and occasionally providing opportunities for domestication and gene amplification to restore and improve functionality. There is still much to be learned from the future comparative genomic studies of chromosome-sized and haplotype-aware assemblies, and from post-genomic studies elucidating genetic and epigenetic regulatory phenomena across short and long evolutionary distances in the metazoan tree of life. Glossary Polyploidy: having more than the usual diploid set of homologous chromosomes Allopolyploidy: a form of polyploidy that results from interspecific hybridization Autopolyploidy: a form of polyploidy that results from chromosome redoubling in the same species Paleopolyploidy: ancient polyploidy Neopolyploidy: recent polyploidy Homeologs: pairs of genes originated by speciation and brought back together by allopolyploidization Ohnologs: same as homeologs, named after S. -

The Chromosome-Based Lavender Genome Provides New Insights Into

Li et al. Horticulture Research (2021) 8:53 Horticulture Research https://doi.org/10.1038/s41438-021-00490-6 www.nature.com/hortres ARTICLE Open Access The chromosome-based lavender genome provides new insights into Lamiaceae evolution and terpenoid biosynthesis Jingrui Li1,2, Yiming Wang 3,YanmeiDong1,2, Wenying Zhang1,2,DiWang1, Hongtong Bai1,KuiLi3,HuiLi1 and Lei Shi1 Abstract The aromatic shrub Lavandula angustifolia produces various volatile terpenoids that serve as resources for essential oils and function in plant-insect communication. To better understand the genetic basis of the terpenoid diversity in lavender, we present a high-quality reference genome for the Chinese lavender cultivar ‘Jingxun 2’ using PacBio and Hi-C technologies to anchor the 894.50 Mb genome assembly into 27 pseudochromosomes. In addition to the γ triplication event, lavender underwent two rounds of whole-genome duplication (WGD) during the Eocene–Oligocene (29.6 MYA) and Miocene–Pliocene (6.9 MYA) transitions. As a result of tandem duplications and lineage-specific WGDs, gene families related to terpenoid biosynthesis in lavender are substantially expanded compared to those of five other species in Lamiaceae. Many terpenoid biosynthesis transcripts are abundant in glandular trichomes. We further integrated the contents of ecologically functional terpenoids and coexpressed terpenoid biosynthetic genes to construct terpenoid-gene networks. Typical gene clusters, including TPS-TPS, TPS- CYP450, and TPS-BAHD, linked with compounds that primarily function as attractants or repellents, were identified by fl 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; their similar patterns of change during ower development or in response to methyl jasmonate. Comprehensive analysis of the genetic basis of the production of volatiles in lavender could serve as a foundation for future research into lavender evolution, phytochemistry, and ecology. -

Heliconinos De La Colección Entomológica De La Facultad De Ciencias Agronómicas, Villaflores, Chiapas, México

ISSN: 2448-4768 Bol. Soc. Mex. Ento. (n. s.) Número especial 2: 34−38 2016 HELICONINOS DE LA COLECCIÓN ENTOMOLÓGICA DE LA FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS AGRONÓMICAS, VILLAFLORES, CHIAPAS, MÉXICO Ricardo Cabrera-Lopez*, Carlos J. Morales-Morales, Eduardo Aguilar-Astudillo y Julio C. Gómez-Castañeda. Universidad Autónoma de Chiapas, Facultad de Ciencias Agronómicas, Campus V, Carret. Ocozocoautla- Villaflores, km 84, C. P. 30470, Villaflores, Chiapas, México. *Autor para correspondencia: cabrera9328 @hotmail.com Recibido: 15/03/2016; Aceptado: 24/04/2016 RESUMEN: El trabajo se realizó en la Colección Entomológica de la Facultad de Ciencias Agronómicas, Campus V de la Universidad Autónoma de Chiapas (FCA-CV) con el material entomológico de la Subfamilia Heliconiinae Swainson, 1822 (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae), de las cuales se revisaron 202 ejemplares representados en ocho géneros y 16 especies. El género mejor representado fue Heliconius con 68 ejemplares con siete especies: Heliconius charitonia vazquezae Comstock y Brown, 1950; Heliconius erato petiverana (Doubleday, 1847); Heliconius hecale fornarina Hewitson, 1854; Heliconius hecalesia octavia Bates, 1866; Heliconius hortense Guérin-Méneville, 1844; Heliconius ismenius telchinia Doubleday, 1847 y Heliconius sapho leuce Doubleday, 1857. Las especies mejor representadas son Dryas iulia moderata (Rilet, 1926), H. charitonia vazquezae, Agraulis vanillae incarnata (Riley, 1926), Dione juno huascuma (Reakirt, 1966) y Eueides isabella eva (Fabricius, 1793). Los organismos se encuentran depositados en la colección entomológica. Las especies H. hecalesia octavia y Laparus doris transiens Staudinger, 1896 están representadas únicamente por un ejemplar. El estatus de sobrevivencia de H. hecalesia octavia se encuentra presionado en Chiapas debido a los cambios drásticos en los bosques causados por las actividades antropológicas. -

Molecular Phylogeny and Systematics of the Pieridae (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea): Higher Classification and Biogeography

Blackwell Publishing LtdOxford, UKZOJZoological Journal of the Linnean Society0024-4082The Lin- nean Society of London, 2006? 2006 147? 239275 Original Article PHYLOGENY AND SYSTEMATICS OF THE PIERIDAEM. F. BRABY ET AL. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2006, 147, 239–275. With 8 figures Molecular phylogeny and systematics of the Pieridae (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea): higher classification and Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/zoolinnean/article-abstract/147/2/239/2631026 by Harvard Library user on 21 November 2018 biogeography MICHAEL F. BRABY1,2*, ROGER VILA1 and NAOMI E. PIERCE1 1Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, 26 Oxford St, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 2School of Botany and Zoology, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia Received May 2004; accepted for publication October 2005 The systematic relationships of the butterfly family Pieridae are poorly understood. Much of our current under- standing is based primarily on detailed morphological observations made 50–70 years ago. However, the family and its putative four subfamilies and two tribes, have rarely been subjected to rigorous phylogenetic analysis. Here we present results based on an analysis of molecular characters used to reconstruct the phylogeny of the Pieridae in order to infer higher-level classification above the generic level and patterns of historical biogeography. Our sample contained 90 taxa representing 74 genera and six subgenera, or 89% of all genera recognized in the family. Three complementary approaches were -

Ancestral Grass Karyotype Reconstruction Unravels New Mechanisms of Genome Shuffling As a Source of Plant Evolution

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on September 29, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Research Ancestral grass karyotype reconstruction unravels new mechanisms of genome shuffling as a source of plant evolution Florent Murat,1,4 Jian-Hong Xu,2,4 Eric Tannier,3,4 Michael Abrouk,1 Nicolas Guilhot,1 Caroline Pont,1 Joachim Messing,2,5 and Je´roˆme Salse1,5 1INRA, UMR 1095, Laboratoire Ge´ne´tique, Diversite´ et Ecophysiologie des Ce´re´ales, 63100 Clermont Ferrand, France; 2The Plant Genome Initiative at Rutgers (PGIR), Waksman Institute of Microbiology, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Piscataway, New Jersey 08854, USA; 3INRIA Rhoˆne-Alpes, Universite´ de Lyon 1, CNRS UMR5558, Laboratoire Biome´trie et Biologie E´volutive, 69622 Villeurbanne Cedex, France The comparison of the chromosome numbers of today’s species with common reconstructed paleo-ancestors has led to intense speculation of how chromosomes have been rearranged over time in mammals. However, similar studies in plants with respect to genome evolution as well as molecular mechanisms leading to mosaic synteny blocks have been lacking due to relevant examples of evolutionary zooms from genomic sequences. Such studies require genomes of species that belong to the same family but are diverged to fall into different subfamilies. Our most important crops belong to the family of the grasses, where a number of genomes have now been sequenced. Based on detailed paleogenomics, using inference from n = 5–12 grass ancestral karyotypes (AGKs) in terms of gene content and order, we delineated sequence intervals comprising a complete set of junction break points of orthologous regions from rice, maize, sorghum, and Brachypodium genomes, representing three different subfamilies and different polyploidization events. -

Whole-Genome Duplications and Paleopolyploidy Whole-Genome Duplications in Protozoa

Whole-genome duplications and paleopolyploidy Whole-genome duplications in protozoa •Aury et al. (2006) analyzed the unicellular eukaryote Paramecium tetraurelia • most of 40,000 genes arose through at least 3 successive whole-genome duplications • most recent duplication most likely caused an explosion of speciation events that gave rise to the P. aurelia complex (15 sibling species) • some genes have been lost, some retained • many retained (duplicated) genes do not generate functional innovations but are important because of the gene dosage effect Whole-genome duplications in yeast • genome comparison between two yeast species, Saccharomyces cerevisiae (n=16) and Kluyveromyces waltii (n=8) • each region of K. waltii corresponding to two regions of S. cerevisiae •the S. cerevisiae genome underwent a whole-genome duplication after the two yeast species diverged • in nearly every case (95%), accelerated evolution was confined to only one of the two paralogues (= one of the paralogues retained an ancestral function, the other was free to evolve more rapidly and acquired a derived function) Kellis et al. 2004, Nature 428 Whole-genome duplications in yeast Kellis et al. 2004, Nature 428 a) after divergence from K. waltii, the Saccharomyces lineage underwent a genome duplication event (2 copies of every gene and chromosome) b) duplicated genes underwent were mutated and some lost c) two copies kept for only a small minority of duplicated genes d) the conserved order of duplicated genes (nos. 3-13) across different chromosomal segments e) comparison between genomes of S. cerevisiae and K. waltii reveals the duplicated nature of the S. cerevisiae genome Duplicated nature of the S.