DNA Metabolism in Mycobacterium Leprae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IMPDH2: a New Gene Associated with Dominant Juvenile-Onset Dystonia-Tremor Disorder

www.nature.com/ejhg BRIEF COMMUNICATION OPEN IMPDH2: a new gene associated with dominant juvenile-onset dystonia-tremor disorder 1,8 1,8 2 3 1,4 2 5 Anna Kuukasjärvi , Juan✉ C. Landoni , Jyrki Kaukonen , Mika Juhakoski , Mari Auranen , Tommi Torkkeli , Vidya Velagapudi and Anu Suomalainen 1,6,7 © The Author(s) 2021 The aetiology of dystonia disorders is complex, and next-generation sequencing has become a useful tool in elucidating the variable genetic background of these diseases. Here we report a deleterious heterozygous truncating variant in the inosine monophosphate dehydrogenasegene(IMPDH2) by whole-exome sequencing, co-segregating with a dominantly inherited dystonia-tremor disease in a large Finnish family. We show that the defect results in degradation of the gene product, causing IMPDH2 deficiency in patient cells. IMPDH2 is the first and rate-limiting enzyme in the de novo biosynthesis of guanine nucleotides, a dopamine synthetic pathway previously linked to childhood or adolescence-onset dystonia disorders. We report IMPDH2 as a new gene to the dystonia disease entity. The evidence underlines the important link between guanine metabolism, dopamine biosynthesis and dystonia. European Journal of Human Genetics; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-021-00939-1 INTRODUCTION The disease-onset was between 9 and 20 years of age. Table 1 Dystonias are rare movement disorders characterised by sustained or summarises the clinical presentations. intermittent muscle contractions causing abnormal, often repetitive, movements and/or postures. Dystonia can manifest as an isolated Case report symptom or combined with e.g. parkinsonism or myoclonus [1]. While Patient II-6 is a 46-year-old woman. -

B Number Gene Name Mrna Intensity Mrna

sample) total list predicted B number Gene name assignment mRNA present mRNA intensity Gene description Protein detected - Membrane protein membrane sample detected (total list) Proteins detected - Functional category # of tryptic peptides # of tryptic peptides # of tryptic peptides detected (membrane b0002 thrA 13624 P 39 P 18 P(m) 2 aspartokinase I, homoserine dehydrogenase I Metabolism of small molecules b0003 thrB 6781 P 9 P 3 0 homoserine kinase Metabolism of small molecules b0004 thrC 15039 P 18 P 10 0 threonine synthase Metabolism of small molecules b0008 talB 20561 P 20 P 13 0 transaldolase B Metabolism of small molecules chaperone Hsp70; DNA biosynthesis; autoregulated heat shock b0014 dnaK 13283 P 32 P 23 0 proteins Cell processes b0015 dnaJ 4492 P 13 P 4 P(m) 1 chaperone with DnaK; heat shock protein Cell processes b0029 lytB 1331 P 16 P 2 0 control of stringent response; involved in penicillin tolerance Global functions b0032 carA 9312 P 14 P 8 0 carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase, glutamine (small) subunit Metabolism of small molecules b0033 carB 7656 P 48 P 17 0 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase large subunit Metabolism of small molecules b0048 folA 1588 P 7 P 1 0 dihydrofolate reductase type I; trimethoprim resistance Metabolism of small molecules peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase (PPIase), involved in maturation of b0053 surA 3825 P 19 P 4 P(m) 1 GenProt outer membrane proteins (1st module) Cell processes b0054 imp 2737 P 42 P 5 P(m) 5 GenProt organic solvent tolerance Cell processes b0071 leuD 4770 P 10 P 9 0 isopropylmalate -

Identification of the Binding Site for Ammonia in GMP Reductase

Identification of the binding site for ammonia in GMP reductase Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of Biology Lizbeth Hedstrom, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Molecular and Cell Biology by Tianjiong Yao February 2015 Copyright by Tianjiong Yao © 2015 ABSTRACT Identification of the binding site for ammonia in GMP reductase A thesis presented to the Department of Biology Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Waltham, Massachusetts By Tianjiong Yao The overall reaction of guanosine monophosphate reductase (GMPR) converts GMP to IMP by using NADPH as a cofactor and it includes two sub-steps: (1) a deamination step that releases ammonia from GMP and forms the intermediate E-XMP*; (2) a hydride transfer step that converts E-XMP* to IMP along with the oxidation of NADPH. The hydride transfer step is the rate limiting step, yet we failed to observe a burst of ammonia release. Meanwhile ammonia cannot stay in the same place where it is formed otherwise it will block NADPH. This observation suggests that ammonia remains bound to the enzyme during the hydride transfer step and there exists ammonia holding site after its release from the formation site. We identified a possible ammonia holding site by inspection of crystal structure of human GMPR type 2. Three candidate amino acids were selected and probed by site directed mutagenesis. The substitutions of all three residues decreased the reduction of GMP at least 50 fold and the oxidation of IMP at least 40 fold, and reduced the intermediate production at least 2 fold. -

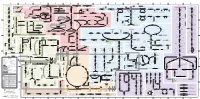

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information (a) (b) Figure S1. Resistant (a) and sensitive (b) gene scores plotted against subsystems involved in cell regulation. The small circles represent the individual hits and the large circles represent the mean of each subsystem. Each individual score signifies the mean of 12 trials – three biological and four technical. The p-value was calculated as a two-tailed t-test and significance was determined using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure; false discovery rate was selected to be 0.1. Plots constructed using Pathway Tools, Omics Dashboard. Figure S2. Connectivity map displaying the predicted functional associations between the silver-resistant gene hits; disconnected gene hits not shown. The thicknesses of the lines indicate the degree of confidence prediction for the given interaction, based on fusion, co-occurrence, experimental and co-expression data. Figure produced using STRING (version 10.5) and a medium confidence score (approximate probability) of 0.4. Figure S3. Connectivity map displaying the predicted functional associations between the silver-sensitive gene hits; disconnected gene hits not shown. The thicknesses of the lines indicate the degree of confidence prediction for the given interaction, based on fusion, co-occurrence, experimental and co-expression data. Figure produced using STRING (version 10.5) and a medium confidence score (approximate probability) of 0.4. Figure S4. Metabolic overview of the pathways in Escherichia coli. The pathways involved in silver-resistance are coloured according to respective normalized score. Each individual score represents the mean of 12 trials – three biological and four technical. Amino acid – upward pointing triangle, carbohydrate – square, proteins – diamond, purines – vertical ellipse, cofactor – downward pointing triangle, tRNA – tee, and other – circle. -

Developmental Disorder Associated with Increased Cellular Nucleotidase Activity (Purine-Pyrimidine Metabolism͞uridine͞brain Diseases)

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 94, pp. 11601–11606, October 1997 Medical Sciences Developmental disorder associated with increased cellular nucleotidase activity (purine-pyrimidine metabolismyuridineybrain diseases) THEODORE PAGE*†,ALICE YU‡,JOHN FONTANESI‡, AND WILLIAM L. NYHAN‡ Departments of *Neurosciences and ‡Pediatrics, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093 Communicated by J. Edwin Seegmiller, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA, August 7, 1997 (received for review June 26, 1997) ABSTRACT Four unrelated patients are described with a represent defects of purine metabolism, although no specific syndrome that included developmental delay, seizures, ataxia, enzyme abnormality has been identified in these cases (6). In recurrent infections, severe language deficit, and an unusual none of these disorders has it been possible to delineate the behavioral phenotype characterized by hyperactivity, short mechanism through which the enzyme deficiency produces the attention span, and poor social interaction. These manifesta- neurological or behavioral abnormalities. Therapeutic strate- tions appeared within the first few years of life. Each patient gies designed to treat the behavioral and neurological abnor- displayed abnormalities on EEG. No unusual metabolites were malities of these disorders by replacing the supposed deficient found in plasma or urine, and metabolic testing was normal metabolites have not been successful in any case. except for persistent hypouricosuria. Investigation of purine This report describes four unrelated patients in whom and pyrimidine metabolism in cultured fibroblasts derived developmental delay, seizures, ataxia, recurrent infections, from these patients showed normal incorporation of purine speech deficit, and an unusual behavioral phenotype were bases into nucleotides but decreased incorporation of uridine. -

Supplements Inference of Cancer Mechanisms Through Computational Systems Analysis

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Molecular BioSystems. This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2017 Supplements Inference of Cancer Mechanisms through Computational Systems Analysis Zhen Qi and Eberhard O. Voit Mathematical model of purine metabolism in human. A published kinetic model of human purine metabolism was used as a computational platform; it consists of 16 ordinary differential equations with 37 fluxes 1, 2. In the literature, the fluxes were formulated either as traditional Michaelis-Menten kinetics or as power law functions under the tenets of Biochemical Systems Theory 3. Here we chose the latter. Many parameters were obtained from experimental and clinical data in humans, and the remaining values were estimated using biological constraints, such as the ratio of adenine and guanine in nucleic acids, which is approximately 3/2, or the fact that normal subjects excrete about 420 mg per day of UA in urine. A detailed analysis of the steady-state properties of the mathematical model demonstrated that the steady state is stable and robust. Analysis also showed that the model is not sensitive to parameter changes. Simulations of normal and pathological perturbations of purine metabolism yielded consistent results with some representative biochemical and clinical observations. All these analyses are described in great detail in the literature 3. Implementation of enzyme activities altered by cancer. Weber discovered several changes in the enzyme activities of purine metabolism in human renal carcinoma cells 4. The affected enzymes and their fold changes compared to normal kidney cells are listed in Table S4. These alterations are expected to result in changed metabolite levels between normal human cells and human renal cell carcinoma, which were computed with the mathematical model, and the values at the corresponding steady state are shown in Table 1 in the Text. -

Micrtxilnns International 300 N.Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Ml 48106

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note wül appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right m equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Comparison of Gene Expression Profiling in Pressure and Volume

1029 Hypertens Res Vol.29 (2006) No.12 p.1029-1045 Original Article Comparison of Gene Expression Profiling in Pressure and Volume Overload–Induced Myocardial Hypertrophies in Rats Hiroshi MIYAZAKI1), Naoki OKA1), Akimasa KOGA1), Haruya OHMURA1), Tamenobu UEDA1), and Tsutomu IMAIZUMI1),2) Gene expression profiling has been conducted in rat hearts subjected to pressure overload (PO). However, pressure and volume overload produce morphologically and functionally distinct forms of cardiac hypertro- phy. Surprisingly, gene expression profiling has not been reported for in an animal model of volume over- load (VO). We therefore compared the gene expression profiles in the hypertrophied myocardium of rats subjected to PO and VO using DNA chip technology (Affymetrix U34A). Constriction of the abdominal aorta and abdominal aortocaval shunting were used to induce PO and VO, respectively. The gene expression pro- files of the left ventricle (LV) 4 weeks after the procedure were analyzed by DNA chips. There were compa- rable increases in the left ventricular weight/body weight ratio in rats subjected to PO and VO. Echocardiography revealed concentric hypertrophy in the PO animals, but eccentric hypertrophy in the rats subjected to VO. The expressions of many genes were altered in VO, PO, or both. Among the genes that were upregulated in both forms of hypertrophy, greatly increased expressions of B-type natriuretic peptide, lysyl oxidase–like protein 1 and metallothionein-1 (MT) were confirmed by real-time reverse transcription– polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Because free radicals are increased in the hypertrophied heart and may contribute to apoptosis, we examined the role of MT, a free radical scavenger, in apoptosis. -

O O2 Enzymes Available from Sigma Enzymes Available from Sigma

COO 2.7.1.15 Ribokinase OXIDOREDUCTASES CONH2 COO 2.7.1.16 Ribulokinase 1.1.1.1 Alcohol dehydrogenase BLOOD GROUP + O O + O O 1.1.1.3 Homoserine dehydrogenase HYALURONIC ACID DERMATAN ALGINATES O-ANTIGENS STARCH GLYCOGEN CH COO N COO 2.7.1.17 Xylulokinase P GLYCOPROTEINS SUBSTANCES 2 OH N + COO 1.1.1.8 Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase Ribose -O - P - O - P - O- Adenosine(P) Ribose - O - P - O - P - O -Adenosine NICOTINATE 2.7.1.19 Phosphoribulokinase GANGLIOSIDES PEPTIDO- CH OH CH OH N 1 + COO 1.1.1.9 D-Xylulose reductase 2 2 NH .2.1 2.7.1.24 Dephospho-CoA kinase O CHITIN CHONDROITIN PECTIN INULIN CELLULOSE O O NH O O O O Ribose- P 2.4 N N RP 1.1.1.10 l-Xylulose reductase MUCINS GLYCAN 6.3.5.1 2.7.7.18 2.7.1.25 Adenylylsulfate kinase CH2OH HO Indoleacetate Indoxyl + 1.1.1.14 l-Iditol dehydrogenase L O O O Desamino-NAD Nicotinate- Quinolinate- A 2.7.1.28 Triokinase O O 1.1.1.132 HO (Auxin) NAD(P) 6.3.1.5 2.4.2.19 1.1.1.19 Glucuronate reductase CHOH - 2.4.1.68 CH3 OH OH OH nucleotide 2.7.1.30 Glycerol kinase Y - COO nucleotide 2.7.1.31 Glycerate kinase 1.1.1.21 Aldehyde reductase AcNH CHOH COO 6.3.2.7-10 2.4.1.69 O 1.2.3.7 2.4.2.19 R OPPT OH OH + 1.1.1.22 UDPglucose dehydrogenase 2.4.99.7 HO O OPPU HO 2.7.1.32 Choline kinase S CH2OH 6.3.2.13 OH OPPU CH HO CH2CH(NH3)COO HO CH CH NH HO CH2CH2NHCOCH3 CH O CH CH NHCOCH COO 1.1.1.23 Histidinol dehydrogenase OPC 2.4.1.17 3 2.4.1.29 CH CHO 2 2 2 3 2 2 3 O 2.7.1.33 Pantothenate kinase CH3CH NHAC OH OH OH LACTOSE 2 COO 1.1.1.25 Shikimate dehydrogenase A HO HO OPPG CH OH 2.7.1.34 Pantetheine kinase UDP- TDP-Rhamnose 2 NH NH NH NH N M 2.7.1.36 Mevalonate kinase 1.1.1.27 Lactate dehydrogenase HO COO- GDP- 2.4.1.21 O NH NH 4.1.1.28 2.3.1.5 2.1.1.4 1.1.1.29 Glycerate dehydrogenase C UDP-N-Ac-Muramate Iduronate OH 2.4.1.1 2.4.1.11 HO 5-Hydroxy- 5-Hydroxytryptamine N-Acetyl-serotonin N-Acetyl-5-O-methyl-serotonin Quinolinate 2.7.1.39 Homoserine kinase Mannuronate CH3 etc. -

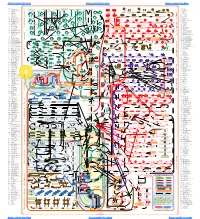

Fullsubwaymap221.Pdf

A B C D E F G H I J K L M Aldose reductase Sorbitol dehydrogenase Cholesterol synthesis Glycogen and galactose metabolism (branch point only) (debranching) glucose sorbitol fructose Aromatic amino acid metabolism Purine synthesis Pyrimidine synthesis glycogen (n+1) phenylacetate triiodothyronine (T3) dopaquinone melanin + + thyroxine (T4) (multiple steps) (many cycles) P 4' NADPH NADP NAD NADH acetyl-CoA x2 i Debranching enzyme 3' - α-1,4 bonds Aromatic amino acid 5-phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate (PRPP) HCO B 2' P 3 (branching) Glycogen 6 i (multiple steps) O H O (multiple steps) Tyrosinase O H O 1' 2 2 2 2 B 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Pentose phosphate pathway Phenylalanine Tyrosine decarboxylase 6 Dopamine B Thiolase phosphorylase -5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 Transaminase 6 glutamine 2 ATP (many cycles) Glycogen Glucose-6-phosphatase Dehydrogenase hydroxylase hydroxylase (DOPA decarboxylase) β-hydroxylase Methyltransferase 10 UDP 4:4 Transferase ATP glutathione (reduced) H O phenyllactate phenylpyruvate phenylalanine tyrosine dihydroxy- dopamine Glutamine PRPP CoA synthase Hexokinase or (in endoplasmic reticulum) 2 2 norepinephrine epinephrine glutamine Carbamoyl 9 1' phenylanine amidotransferase (GPAT) glutamate glycogen (n) Glutathione reductase Glutathione peroxidase + phosphate glycogen (n) -5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 2' 3' 4' glucokinase 8 NADP NADPH glutamate α-ketoglutarate CO2 O H O Glycosyl (4:6) UDP-glucose ADP (L-DOPA) 2 2 synthetase II glutathione (oxidized) 2 H O α-ketoglutarate PPi glutamate acetoacetyl-CoA 7 1 Glucose -1,6-Glucosidase -

(GMPR) Variant in a Patient with a Late‐Onset Disorde

Received: 16 August 2019 Revised: 18 September 2019 Accepted: 27 September 2019 DOI: 10.1111/cge.13652 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Identification of a novel heterozygous guanosine monophosphate reductase (GMPR) variant in a patient with a late-onset disorder of mitochondrial DNA maintenance Ewen W. Sommerville1 | Ilaria Dalla Rosa2 | Masha M. Rosenberg3 | Francesco Bruni4,1 | Kyle Thompson1 | Mariana Rocha1 | Emma L. Blakely1 | Langping He1 | Gavin Falkous1 | Andrew M. Schaefer1 | Patrick Yu-Wai-Man5,6,7 | Patrick F. Chinnery8 | Lizbeth Hedstrom3,9 | Antonella Spinazzola2,10 | Robert W. Taylor1 | Gráinne S. Gorman1 1Wellcome Centre for Mitochondrial Research, Institute of Neuroscience, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK 2Department of Clinical and Movement Neurosciences, UCL Queens Square Institute of Neurology, Royal Free Campus, University College London, London,UK 3Department of Biology, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA 4Department of Biosciences, Biotechnologies and Biopharmaceutics, University of Bari “ldo Moro”, Bari, Italy 5NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at Moorfields Eye Hospital and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, London, UK 6MRC Mitochondrial Biology Unit, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK 7Cambridge Centre for Brain Repair, Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK 8Department of Clinical Neuroscience & Medical Research Council Mitochondrial Biology Unit, School of Clinical Medicine, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK 9Department of Chemistry, Brandeis University, 415 South St., Waltham, MA 10MRC Centre for Neuromuscular Diseases, UCL Institute of Neurology and National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, London, UK Correspondence Professor Robert W. Taylor, Wellcome Centre Abstract for Mitochondrial Research, Institute of Autosomal dominant progressive external ophthalmoplegia (adPEO) is a late-onset, Neuroscience, Newcastle University, Framlington Place, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE2 Mendelian mitochondrial disorder characterised by paresis of the extraocular muscles, 4HH, UK. -

Figure S1. Gene Ontology Classification of Abeliophyllum Distichum Leaves Extract-Induced Degs

Figure S1. Gene ontology classification of Abeliophyllum distichum leaves extract-induced DEGs. The results are summarized in three main categories: Biological process, Cellular component and Molecular function. Figure S2. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis using Abeliophyllum distichum leaves extract-DEGs (A). Venn diagram analysis of DEGs involved in PI3K/Akt signaling pathway and Rap1 signaling pathway (B). Figure S3. The expression (A) and protein levels (B) of Akt3 in AL-treated SK-MEL2 cells. Values with different superscripted letters are significantly different (p < 0.05). Table S1. Abeliophyllum distichum leaves extract-induced DEGs. log2 Fold Gene name Gene description Change A2ML1 alpha-2-macroglobulin-like protein 1 isoform 2 [Homo sapiens] 3.45 A4GALT lactosylceramide 4-alpha-galactosyltransferase [Homo sapiens] −1.64 ABCB4 phosphatidylcholine translocator ABCB4 isoform A [Homo sapiens] −1.43 ABCB5 ATP-binding cassette sub-family B member 5 isoform 1 [Homo sapiens] −2.99 ABHD17C alpha/beta hydrolase domain-containing protein 17C [Homo sapiens] −1.62 ABLIM2 actin-binding LIM protein 2 isoform 1 [Homo sapiens] −2.53 ABTB2 ankyrin repeat and BTB/POZ domain-containing protein 2 [Homo sapiens] −1.48 ACACA acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 isoform 1 [Homo sapiens] −1.76 ACACB acetyl-CoA carboxylase 2 precursor [Homo sapiens] −2.03 ACSM1 acyl-coenzyme A synthetase ACSM1, mitochondrial [Homo sapiens] −3.05 disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein 19 preproprotein [Homo ADAM19 −1.65 sapiens] disintegrin and metalloproteinase