Conference Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diary Dates MAY: Phone: Monday 16Th May – - (02) 6347 1207 Friday 20Th May HSC & Preliminary VET Workplacements

Quandialla Central School “Together we provide opportunities to succeed” th Newsletter Tuesday, 17 May, 2011 (Week B No. 13) Address: Third Street Quandialla 2721 Diary Dates MAY: Phone: Monday 16th May – - (02) 6347 1207 Friday 20th May HSC & Preliminary VET Workplacements Wed. 18th May School Cross Country Fax: th (02) 6347 1248 Thursday 19 May Money Olympics – CBA Bank visit (Years 3-6) Monday 23rd May-27th Preliminary Half Yearly Exams Email: Wed. 25th May Bookfair for Pre-school Parents (9.00 – 10.00 a.m.) quandialla- Thursday 26th May Bookfair for Parents, Students & Community Members c.school@ (1.00 – 2.20 p.m.) prior to School Assembly det.nsw.edu.au Thursday 26th May Assembly – 2.20 p.m. Monday 30th May – Website: Friday 3rd June Preliminary Half Yearly Exams & Years 7-10 Exams http://www. Friday 3rd June Forbes Small Schools Athletics Carnival (Primary) quandialla- c.schools.nsw.edu .au/sws/view /home.node Principal: Phil Foster Assistant Principal: Wendy Robinson Head Teacher of Secondary Studies: Lisa Varjavandi School Administration Manager Robin Dowsett Parents and Theresa, Taren, Robert, Caitlyn and Ellie all enjoyed participating in Aboriginal for a day. Citizens Association: Aboriginal for a day President: The Aboriginal for a day program has been organised by Mr Dale, and is scheduled for Cheryl Troy Tuesday 17 May. Secretary: The program is designed to involve all students in activities that build awareness of Leanne Penfold Aboriginal culture. Activities include an Aboriginal art workshop, Dance with the Yidaki and Storytelling and cultural history. Treasurer: Robin Dowsett - 1 - The day will conclude with students presenting a dance performance or boomerang throwing. -

Bringing Us Together SUSTAINING WEDDIN INTO the FUTURE

WEDDIN 2026 2017-2026 COMMUNITY STRATEGIC PLAN Bringing Us Together SUSTAINING WEDDIN INTO THE FUTURE Weddin 2026 Community Strategic Plan - Bringing Us Together 1 WHERE ARE WE NOW 7 WHERE ARE WE GOING 9 Community consultation 10 Informing Where We are Going 14 2013-2026 PLAN PRIORITIES 14 Fiscal Responsibility, Management and FFTF 15 Projects and Policies Identified by Council Elected in 2016 17 CONSULTATION AND RESEARCH OUTCOMES – ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY 21 WEDDIN 2026: THE COMMUNITY STRATEGIC PLAN 23 WHAT IS A STRATEGY? 25 WHAT IS ASSESSING PROGRESS? 26 NO. 1 – Collaborative Wealth Building (Strong, diverse and resilient local economy) 26 STRATEGIES 27 ASSESSING PROGRESS 28 NO. 2 – Innovation in Service Delivery (Healthy, safe, and educated community) 29 STRATEGIES 30 ASSESSING PROGRESS 31 NO. 3 – Democratic and engaged community supported by efficient internal systems 32 STRATEGIES 32 ASSESSING PROGRESS 33 NO. 4 – Culturally rich, vibrant and inclusive community 34 STRATEGIES 34 ASSESSING PROGRESS 35 NO. 5 – Sustainable natural, agricultural and built environments 36 STRATEGIES 36 ASSESSING PROGRESS 37 NO. 6 – Shire assets and services delivered effectively and efficiently 38 STRATEGIES 39 ASSESSING PROGRESS 40 Weddin 2026 Community Strategic Plan - Bringing Us Together 2 WEDDIN SHIRE TO FORBES FORBES TO CREEK TO GOOLOOGONG WHEATLEYS BEWLEYS ROAD ROAD ROAD RAILWAY HIGHWAY WIRRINYA ROAD FORBES OOMA STEWARTS WAY BOUNDARY ROAD GAP ROAD NEW LANE ROAD CREEK NEWELL ROAD LANE MORTRAY CREEK WARRADERRY BALD SANDHILL KEITHS GUINEA PIG -

Seasonal Buyer's Guide

Seasonal Buyer’s Guide. Appendix New South Wales Suburb table - May 2017 Westpac, National suburb level appendix Copyright Notice Copyright © 2017CoreLogic Ownership of copyright We own the copyright in: (a) this Report; and (b) the material in this Report Copyright licence We grant to you a worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free, revocable licence to: (a) download this Report from the website on a computer or mobile device via a web browser; (b) copy and store this Report for your own use; and (c) print pages from this Report for your own use. We do not grant you any other rights in relation to this Report or the material on this website. In other words, all other rights are reserved. For the avoidance of doubt, you must not adapt, edit, change, transform, publish, republish, distribute, redistribute, broadcast, rebroadcast, or show or play in public this website or the material on this website (in any form or media) without our prior written permission. Permissions You may request permission to use the copyright materials in this Report by writing to the Company Secretary, Level 21, 2 Market Street, Sydney, NSW 2000. Enforcement of copyright We take the protection of our copyright very seriously. If we discover that you have used our copyright materials in contravention of the licence above, we may bring legal proceedings against you, seeking monetary damages and/or an injunction to stop you using those materials. You could also be ordered to pay legal costs. If you become aware of any use of our copyright materials that contravenes or may contravene the licence above, please report this in writing to the Company Secretary, Level 21, 2 Market Street, Sydney NSW 2000. -

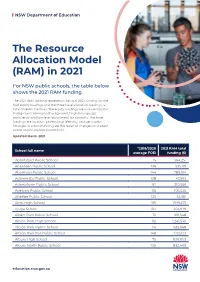

The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021

NSW Department of Education The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021 For NSW public schools, the table below shows the 2021 RAM funding. The 2021 RAM funding represents the total 2021 funding for the four equity loadings and the three base allocation loadings, a total of seven loadings. The equity loadings are socio-economic background, Aboriginal background, English language proficiency and low-level adjustment for disability. The base loadings are location, professional learning, and per capita. Changes in school funding are the result of changes to student needs and/or student enrolments. Updated March 2021 *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Abbotsford Public School 15 364,251 Aberdeen Public School 136 535,119 Abermain Public School 144 786,614 Adaminaby Public School 108 47,993 Adamstown Public School 62 310,566 Adelong Public School 116 106,526 Afterlee Public School 125 32,361 Airds High School 169 1,919,475 Ajuga School 164 203,979 Albert Park Public School 111 251,548 Albion Park High School 112 1,241,530 Albion Park Public School 114 626,668 Albion Park Rail Public School 148 1,125,123 Albury High School 75 930,003 Albury North Public School 159 832,460 education.nsw.gov.au NSW Department of Education *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Albury Public School 55 519,998 Albury West Public School 156 527,585 Aldavilla Public School 117 681,035 Alexandria Park Community School 58 1,030,224 Alfords Point Public School 57 252,497 Allambie Heights Public School 15 -

Western NSW District District Data Profile Murrumbidgee, Far West and Western NSW Contents

Western NSW District District Data Profile Murrumbidgee, Far West and Western NSW Contents Introduction 4 Population – Western NSW 7 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Population 13 Country of Birth 17 Language Spoken at Home 21 Migration Streams 28 Children & Young People 30 Government Schools 30 Early childhood development 42 Vulnerable children and young people 55 Contact with child protection services 59 Economic Environment 61 Education 61 Employment 65 Income 67 Socio-economic advantage and disadvantage 69 Social Environment 71 Community safety and crime 71 2 Contents Maternal Health 78 Teenage pregnancy 78 Smoking during pregnancy 80 Australian Mothers Index 81 Disability 83 Need for assistance with core activities 83 Households and Social Housing 85 Households 85 Tenure types 87 Housing affordability 89 Social housing 91 3 Contents Introduction This document presents a brief data profile for the Western New South Wales (NSW) district. It contains a series of tables and graphs that show the characteristics of persons, families and communities. It includes demographic, housing, child development, community safety and child protection information. Where possible, we present this information at the local government area (LGA) level. In the Western NSW district there are twenty-two LGAS: • Bathurst Regional • Blayney • Bogan • Bourke • Brewarrina • Cabonne • Cobar • Coonamble • Cowra • Forbes • Gilgandra • Lachlan • Mid-western Regional • Narromine • Oberon • Orange • Parkes • Walgett • Warren • Warrumbungle Shire • Weddin • Western Plains Regional The data presented in this document is from a number of different sources, including: • Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) • Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) • NSW Health Stats • Australian Early Developmental Census (AEDC) • NSW Government administrative data. -

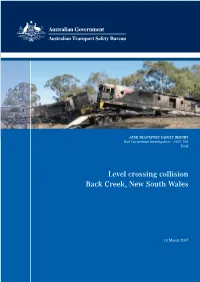

2007-001 Back Creek

ATSB TRANSPORT SAFETY REPORT Rail Occurrence Investigation – 2007/001 Final Level crossing collision Back Creek, New South Wales 10 March 2007 ATSB TRANSPORT SAFETY REPORT Rail Occurrence Investigation 2007/001 Final Level crossing collision Back Creek, New South Wales 10 March 2007 Released in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 - i - Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Postal address: PO Box 967, Civic Square ACT 2608 Office location: 15 Mort Street, Canberra City, Australian Capital Territory Telephone: 1800 621 372; from overseas + 61 2 6274 6590 Accident and incident notification: 1800 011 034 (24 hours) Facsimile: 02 6274 6474; from overseas + 61 2 6274 6130 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.atsb.gov.au © Commonwealth of Australia 2008. This work is copyright. In the interests of enhancing the value of the information contained in this publication you may copy, download, display, print, reproduce and distribute this material in unaltered form (retaining this notice). However, copyright in the material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you want to use their material you will need to contact them directly. Subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968, you must not make any other use of the material in this publication unless you have the permission of the Australian Transport Safety Bureau. Please direct requests for further information or authorisation to: Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Copyright Law Branch Attorney-General’s Department, Robert Garran Offices, National Circuit, Barton ACT 2600 www.ag.gov.au/cca ISBN and formal report title: see ‘Document retrieval information’ on page v. -

Department of Motor Transport, 1981-82

PRINCIPAL OFFICERS OF THE DEPARTMENT OF MOTOR TRANSPORT AS AT 30TH JUNE, 1982. J.W. (Jack) Davies Commissioner H.L. (Harry) Camkin M.J. (Michael) Butler A.J. (Arthur) Percival Director Executive Director Executive Director Traffic Authority of NSW (Policy Analysis Unit) (Management) D.G. (Don) Bell K.R. (Kevin) Bain Chief Superintendent Secretary COVER: Impression of new office complex for the Department's Southern Region in Wagga Wagga. NEW SOUTH WALES The Hon. P.F. Cox, M.P., Minister for Transport, SYDNEY. Dear Mr. Cox, It is with pleasure that I submit, for your information and presentation to Parliament, the Annual Report of the Department of Motor Transport for the year ended 30th June, 1982. The report briefly describes the Department's aims and functions and summarises its activities and achievements. Included also are the financial results for the year and some explanatory information about the Department's policies and functions. I again acknowledge, with appreciation, the loyal and able assistance given by the staff of the Department during the year. Yours faithfully, ISSN 0467 5290 CONTENTS PAGE Aims of the Department 1 Legislative Functions 1 Finances 1 Policy Developments and Legal Activities 4 Motor Vehicle Registrations and Drivers' Licences 12 Commercial Transport Services 16 Mechanical Engineering Activities 21 Other Functions, Staff, Premises and Data Processing 24 APPENDICES No. TOPIC 1. Source and Application of Funds 30 & 31 2. Road Transport and Traffic Fund 32 & 33 3. Public Vehicles Fund 34 4. Payments from Public Vehicles Fund to Councils and other Local Road Authorities 35 5. Notes to accounts shown in Appendices 1, 2, 3 and 4 36 6. -

'Soils' and 'Vegetation'?

Is there a close association between ‘soils’ and ‘vegetation’? A case study from central western New South Wales M.O. Rankin1, 3, W.S Semple2, B.W. Murphy1 and T.B. Koen1 1 Department of Natural Resources, PO Box 445, Cowra, NSW 2794, AUSTRALIA 2 Department of Natural Resources, PO Box 53, Orange, NSW 2800, AUSTRALIA 3 Corresponding author, email: [email protected] Abstract: The assumption that ‘soils’ and ‘vegetation’ are closely associated was tested by describing soils and vegetation along a Travelling Stock Reserve west of Grenfell, New South Wales (lat 33° 55’S, long 147° 45’E). The transect was selected on the basis of (a) minimising the effects of non-soil factors (human interference, climate and relief) on vegetation and (b) the presence of various soil and vegetation types as indicated by previous mapping. ‘Soils’ were considered at three levels: soil landscapes (a broad mapping unit widely used in central western NSW), soil types (according to a range of classifications) and soil properties (depth, pH, etc.). ‘Vegetation’ was considered in three ways: vegetation type (in various classifications), density/floristic indices (density of woody species, abundance of native species, etc.) and presence/absence of individual species. Sites along the transect were grouped according to soil landscapes or soil types and compared to vegetation types or indices recorded at the sites. Various measures indicated low associations between vegetation types and soil landscapes or soil types. Except for infrequent occurrences of a soil type or landscape, any one soil type or landscape was commonly associated with a number of vegetation types and any one vegetation type was associated with a number of soil landscapes or soil types. -

Delivery Program 2017-2021

WEDDIN SHIRE COUNCIL WEDDIN 2026 DELIVERY PROGRAMME 2017-2021 Adopted 15 June 2017 Weddin Shire Council 2017-2021 Delivery Programme 1 INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW 3 INTEGRATED PLANNING & REPORTING 5 DELIVERY PROGRAMME REQUIREMENTS 7 CORPORATE STATEMENTS 9 ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURE 11 ROLES & RESPONSIBILITIES 12 PARTNERS & STAKEHOLDERS 13 DELIVERY PROGRAMME STRUCTURE 14 SO # 1 COLLABORATIVE WEALTH BUILDING (STRONG, DIVERSE AND RESILIENT LOCAL ECONOMY). 19 SO # 2 HEALTHY, SAFE, AND EDUCATED COMMUNITY 24 SO # 3. DEMOCRATIC AND ENGAGED COMMUNITY 28 SO # 4. CULTURALLY RICH, VIBRANT AND INCLUSIVE COMMUNITY 32 SO # 5. CARED FOR NATURAL, AGRICULTURAL & BUILT ENVIRONMENTS 35 SO # 6. WELL MAINTAINED & IMPROVING SHIRE ASSETS AND SERVICES 40 Weddin Shire Council 2017-2021 Delivery Programme 2 INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW It is with pleasure that I present you with Weddin Shire Council’s four-year Delivery Plan (2017-2021) and the 2017-2018 Operational Plan. Weddin Shire Council has seen significant change over the last four years since it developed its first Community Strategic Plan (2013-2023), Delivery Plan and Operational Plan. This Plan reflects these changes. The new Plan is a requirement of the NSW Government and assists the community in better understanding where we are and how we can get to a sustainable future that best meets the whole of community needs. The Weddin Community values its independence and sense of place. Since 2012, the community has continued to express a strong commitment to remaining as an independent Council and improving community amenities so that skills and resources can continue to be attracted to Weddin. In doing so, Weddin embraces the opportunity to work with neighbouring and regional councils and a broad range of government bodies so services can be more efficiently and effectively delivered through a broadly collaborative and inclusive plan. -

Agenda Minutes 18 March 2021

WEDDIN SHIRE COUNCIL All correspondence to be addressed to: The General Manager P.O. Box 125 Camp Street GRENFELL NSW 2810 Phone: (02) 6343 1212 Email: [email protected] Website: www.weddin.nsw.gov.au A.B.N. 73 819 323 291 MINUTES OF THE WEDDIN SHIRE COUNCIL ORDINARY MEETING HELD THURSDAY, 18 MARCH 2021 COMMENCING AT 5:00 PM 11 March 2021 Dear Councillors, NOTICE is hereby given that an ORDINARY MEETING OF THE COUNCIL OF THE SHIRE OF WEDDIN will be held in the Council Chambers, Grenfell on THURSDAY NEXT, 18 MARCH 2021, commencing at 5:00 PM and your attendance is requested. Yours faithfully GLENN CARROLL GENERAL MANAGER 1. OPENING MEETING 2. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF COUNTRY 3. APOLOGIES AND COUNCILLOR LEAVE APPLICATIONS 4. CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES - Ordinary Mtg 18/02/2021 - Extra-Ordinary Mtg 25/02/2021 5. MATTERS ARISING 6. DISCLOSURES OF INTEREST 7. PUBLIC FORUM 8. MAYORAL MINUTE(S) 9. MOTIONS WITH NOTICE 10. CORRESPONDENCE (as per precis attached) 11. REPORTS: (A) General Manager (B) Director Corporate Services (C) Director Engineering (D) Director Environmental Services (E) Delegates 12. ACTION LIST 13. COMMITTEES MINUTES - Quandialla Swimming Pool Ctee Extra-Ordinary Mtg, 05/02/2021 - The Grenfell Henry Lawson Festival of Arts Ctee Mtg, 03/03/2021 - Quandialla Swimming Pool Ctee Mtg, 05/03/2021 - Award Restructuring Consultative Ctee Mtg, 10/03/2021 - OLT Mtg, 16/03/2021 14. TENDERS AND QUOTATIONS 15. QUESTIONS WITH NOTICE 16. CLOSED COUNCIL 17. RETURN TO OPEN COUNCIL 18. REPORT ON CLOSED COUNCIL 19. CLOSURE PRESENT: The Mayor Cr M Liebich in the Chair, Crs P Best, C Bembrick, S O’Byrne, P Diprose, S McKellar, J Parlett, C Brown, and J Niven. -

Inquiry Into Rural and Remote School Education in Australia

HUMAN RIGHTS AND EQUAL OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION INQUIRY INTO RURAL AND REMOTE SCHOOL EDUCATION IN AUSTRALIA Submission prepared by: NSW DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION AND TRAINING 35 BRIDGE STREET SYDNEY CONTENTS SECTION 1. INTRODUCTION The statutory obligations of the Department of Education and Training. The statewide structure for planning and delivering educational services. SECTION 2. THE AVAILABILITY AND ACCESSIBILITY OF PRIMARY AND SECONDARY SCHOOLING IN NSW Refers to the Commission’s Term of Reference 1. SECTION 3. THE QUALITY OF EDUCATIONAL SERVICES AND TECHNOLOGICAL SUPPORT SERVICES Refers to the Commission’s Term of Reference 2. SECTION 4. EDUCATION OF STUDENTS WITH SPECIAL NEEDS Refers to the Commission’s Term of Reference 3, namely whether the education available to children with disabilities, Indigenous children and children from diverse cultural, religious and linguistic backgrounds complies with their human rights. SECTION 5. EXAMPLES OF PROGRAMS FOR STUDENTS, TEACHERS AND THE COMMUNITY OPERATING IN RURAL AREAS OF NEW SOUTH WALES SECTION 6. REVIEW AND CONCLUSION ATTACHMENTS (not included in this electronic version) Section 1: Introduction 1. Profile of Students and Schools in Rural Districts, 1998 2. Agenda 99 Section 2: The Availability and Accessibility of Primary and Secondary Schooling in NSW 3. Schools Attracting Incentive Benefits 4. Rural Schools in the DSP Program by District Section 3: The Quality of Educational Services and Technological Support Services 5. Access Program 6. Bourke High School 1997 Annual Report 7. Report on the Satellite Trial in Open Line, 14 May 1999 8. Aboriginal Identified Positions in Schools and District Offices in Rural and Remote NSW 9. School Attendance Section 4: Education of Students with Special Needs 10. -

Phone: 0263475225 Fax: 0263475214 12Th August, 2013

th Phone: 0263475225 Fax: 0263475214 12 August, 2013 July, 2013 Mobile: 0428 257 475 Email: [email protected] Principal: Judith Gorton Web: www.caragabal-p.schools.nsw.edu.au Success Through Learning Parents and friends of Caragabal Public School Playgroup Weekly Events Dinosaurs at West Wyalong Bears bush bus Monday 1.30 Preschool Tuesday and Friday 9.15 – 3.15 ___________________________________ This Week August Tuesday 13th 8.30 – 11.30 Music with Mrs Blunt via Video Conference. 11.30 CWA Day - Morocco The students enjoyed visiting the Dinosaurs Down Under th travelling road show and mini exhibition by the National Dinosaur Wednesday 14 Museum, Canberra. There was a meteorite made of iron, the th Thursday 15 Miss Gorton and world’s oldest fossil and rocks that were 4.4 billion years old. Mrs Armstrong The students also participated in a talk with international Dance Night th Palaeontologist Matron Rabi, Friday 16 Peter Clifton Tennis Active After School The road show displayed moving, life-like dinosaur models, and th Monday 19 Active After School offered interactive hands-on fossil experiences, including the st rd opportunity to hold the bones of real Australian mega-fauna (like 21 – 23 Miss Gorton @ Primary Principals Conf. the giant wombat, Diprotodon) or touch fossilised ancestors of _________________________________ the Wollemi pine. Mathletics certificates This week bronze certificates go to Penny, Jake, Halle, Billie, Tully, Angus, Rori and Gage. Polly and Jack received a silver and Sadie, a gold certificate. Jake was our highest scorer with 2440 points. Have a great week. Regards, Caragabal Staff Dance Night The Mathletics team sent certificates of achievement in This Thursday evening is our annual dance night.