Technical Report Number In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COUNTRY SECTION United States Fishery Products

Validity date from COUNTRY United States 22/01/2021 00499 SECTION Fishery products Date of publication 28/07/2007 List in force Approval number Name City Regions Activities Remark Date of request 1000025102 GET SEAFOOD, INC. Winter Haven Florida PP 08/04/2013 1000025909 Fagan Alligator Products, Inc. Dade City Florida PP 1000084596 Sea-Trek Enterprises, Inc. East Greenwich Rhode Island PP O! 10/07/2008 1000112376 Pontchartrain Blue Crab Slidell Louisiana PP 14/04/2010 1000113172 Fishermen's Ice & Bait, Inc. Madeira Beach Florida PP 1000113708 Beck's Smokery Pompano Beach Florida PP 1000113902 Colorado Boxed Beef Co. Port Everglades Florida CS 16/11/2011 1000114005 D & D Seafood Corporation Marathon Florida PP 1000114027 BAMA SEA PRODUCTS St. Petersburg Florida PP 1000114048 Moon's Seafood Company W. Melbourne Florida PP O! 1000114049 Glanbia Performance Nutrition (Manufacturing), Inc., Florida Sunrise Florida PP 13/10/2017 Facility 1000114069 Placeres & Sons Seafood Hialeah Florida PP 1000114070 Webb's Seafood, Inc. Youngstown Florida PP 14/10/2009 1000114156 Cox's Wholesale Seafood, Inc. Tampa Florida PP 1000114170 Kings Seafood, Inc. Port Orange Florida PP 1 / 59 List in force Approval number Name City Regions Activities Remark Date of request 1000114326 Optimus, Inc. Dba Marky's Miami Florida PP 1000115645 AMERIQUAL FOODS LLC Evansville Indiana PP 06/02/2019 1000115810 Henriksen Fisheries, Inc Sister Bay Wisconsin PP 1000117125 RB Manufacturing LLC Salt Lake City Utah PP 08/01/2015 1000120312 Stauber Performance Ingredients, Inc. Florida New York PP 08/08/2019 1000120556 Plenus Group, Inc. Lowell Massachusetts PP 06/05/2008 1000120753 GARBO LOBSTER LLC Groton Connecticut PP 17/10/2016 1000121950 True World Foods, NY LLC Elizabeth New Jersey PP Aq 1000122358 Lamonica Fine Foods, Inc. -

Trends in the Utilization and Production of Seafood Byproducts

Advances in Seafood Byproducts 351 Alaska Sea Grant College Program • AK-SG-03-01, 2003 Trends in the Utilization and Production of Seafood Byproducts Hans Nissen Atlas-Stord, Inc., Kansas City, Missouri Abstract Seafood companies in the North Pacific and Alaska generate a significant volume of seafood byproducts and could benefit environmentally and economically by utilizing these byproducts. Today many of the compa- nies have integrated a fish meal plant to process seafood byproduct into valuable high quality fish meal and oil which is sold worldwide in com- petition with other protein meals. In order to justify the investment in a production facility to utilize the byproduct the annual volume must be considered. The trend has been to combine the byproduct from various plants in order to have enough volume to make the operation feasible. In Alaska with many small processors at remote locations this can be a difficult task, and the reason much of the seafood byproduct today is still being dumped or disposed at landfills. We have considered a pro- cess where the byproduct is collected at the different sites and brought to a central location where it is hydrolyzed into silage and dried using a carrier liquid drying process (CLD) producing a stable product that can be marketed worldwide. Introduction As a fish meal equipment manufacturer we are in many cases the first in line to get the call when a fish processor, for various reasons, must con- sider how to utilize the fish byproduct from his process. The reasons can include new environmental regulations regarding disposal of byproduct, or an increase in disposal cost from the local landfill or from the person who hauls the byproduct away. -

Alaska Park Science 19(1): Arctic Alaska Are Living at the Species’ Northern-Most to Identify Habitats Most Frequented by Bears and 4-9

National Park Service US Department of the Interior Alaska Park Science Region 11, Alaska Below the Surface Fish and Our Changing Underwater World Volume 19, Issue 1 Noatak National Preserve Cape Krusenstern Gates of the Arctic Alaska Park Science National Monument National Park and Preserve Kobuk Valley Volume 19, Issue 1 National Park June 2020 Bering Land Bridge Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve National Preserve Denali National Wrangell-St Elias National Editorial Board: Park and Preserve Park and Preserve Leigh Welling Debora Cooper Grant Hilderbrand Klondike Gold Rush Jim Lawler Lake Clark National National Historical Park Jennifer Pederson Weinberger Park and Preserve Guest Editor: Carol Ann Woody Kenai Fjords Managing Editor: Nina Chambers Katmai National Glacier Bay National National Park Design: Nina Chambers Park and Preserve Park and Preserve Sitka National A special thanks to Sarah Apsens for her diligent Historical Park efforts in assembling articles for this issue. Her Aniakchak National efforts helped make this issue possible. Monument and Preserve Alaska Park Science is the semi-annual science journal of the National Park Service Alaska Region. Each issue highlights research and scholarship important to the stewardship of Alaska’s parks. Publication in Alaska Park Science does not signify that the contents reflect the views or policies of the National Park Service, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute National Park Service endorsement or recommendation. Alaska Park Science is found online at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/alaskaparkscience/index.htm Table of Contents Below the Surface: Fish and Our Changing Environmental DNA: An Emerging Tool for Permafrost Carbon in Stream Food Webs of Underwater World Understanding Aquatic Biodiversity Arctic Alaska C. -

Refashioning Production in Bristol Bay, Alaska by Karen E. Hébert A

Wild Dreams: Refashioning Production in Bristol Bay, Alaska by Karen E. Hébert A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in the University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Professor Fernando Coronil, Chair Associate Professor Arun Agrawal Associate Professor Stuart A. Kirsch Associate Professor Barbra A. Meek © Karen E. Hébert 2008 Acknowledgments At a cocktail party after an academic conference not long ago, I found myself in conversation with another anthropologist who had attended my paper presentation earlier that day. He told me that he had been fascinated to learn that something as “mundane” as salmon could be linked to so many important sociocultural processes. Mundane? My head spun with confusion as I tried to reciprocate chatty pleasantries. How could anyone conceive of salmon as “mundane”? I was so confused by the mere suggestion that any chance of probing his comment further passed me by. As I drifted away from the conversation, it occurred to me that a great many people probably deem salmon as mundane as any other food product, even if they may consider Alaskan salmon fishing a bit more exotic. At that moment, I realized that I was the one who carried with me a particularly pronounced sense of salmon’s significance—one that I shared with, and no doubt learned from, the people with whom I conducted research. The cocktail-party exchange made clear to me how much I had thoroughly adopted some of the very assumptions I had set out simply to study. It also made me smile, because it revealed how successful those I got to know during my fieldwork had been in transforming me from an observer into something more of a participant. -

An Ethnography of Old Harbor and Ouzinkie, Alaska

BLACK DUCKS AND SALMON BELLIES An Ethnography of Old Harbor and Ouzinkie, Alaska by Craig Mishler Technical Memorandum No. 7 A Report Produced for the U.S. Minerals Management Service Cooperative Agreement 14-35-0001-30788 March 2001 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Subsistence 333 Raspberry Road Anchorage, Alaska 99518 This report has been reviewed by the Minerals Management Service and approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Service, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. ADA PUBLICATIONS STATEMENT The Alaska Department of Fish and Game operates all of its public programs and activities free from discrimination on the basis of sex, color, race, religion, national origin, age, marital status, pregnancy, parenthood, or disability. For information on alternative formats available for this and other department publications, please contact the department ADA Coordinator at (voice) 907- 465-4120, (TDD) 1-800-478-3548 or (fax) 907-586-6595. Any person who believes she or he has been discriminated against should write to: Alaska Department of Fish and Game PO Box 25526 Juneau, AK 99802-5526 or O.E.O. U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 20240 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ...............................................................................................................................iii List of Figures ...............................................................................................................................iii -

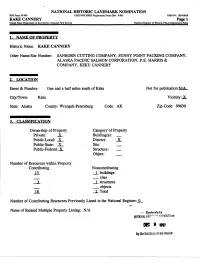

KAKE CANNERY Other Name/Site Number

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 KAKE CANNERY Page 1 United Sates Department of the Interior. National Park Service_______________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: KAKE CANNERY Other Name/Site Number: SANBORN CUTTING COMPANY, SUNNY POINT PACKING COMPANY, ALASKA PACIFIC SALMON CORPORATION, P.E. HARRIS & COMPANY, KEKU CANNERY 2. LOCATION Street & Number: One and a half miles south of Kake Not for publication:MZA_ City/Town: Kake Vicinity :_X_ State: Alaska County: Wrangell-Petersburg Code: AK Zip Code: 99830 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): _ Public-Local: X District: JL Public-State: X Site: _ Public-Federal:_X_ Structure: _ Object: _ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 15 _L buildings _ _ sites _ 2_ ... 1 structures _ _ objects 18 JL Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: JL_ Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A - n of at 4 a D6D 0 by the Secretary of the Intsrior NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) 0MB No. 1024-OMg KAKE CANNERY Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Pom 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

POTENTIAL MARKETS for ALASKA SALMON CANNERY WASTE by Norman B

August 1952 COMMERCIAL FISHERIES REVIEW 5 POTENTIAL MARKETS FOR ALASKA SALMON CANNERY WASTE By Norman B. Wigutoff- INTROOUCfrON Since the beginning of salmon canning in Alaska late in the nineteenth cen tury, waste disposal or utilization has been a problem. The canning process re sults in the use of only two-thirds of the whole fish. The other one-third- head, tail, fins, and viscera or entrails--is discarded. Although reduction plants are successfully operated in areas of Alaska where large volumes of waste are available froll! several canneries, it has proved im practical with present costs to operate the usual type of reduction plant inareas where only one or tvlO canneries are located. Inasmuch as many canneries are lo cated in isolated places, the problem of waste utilization in these areas remains. Between 100,000,000 and 125,000,000 pounds of salmon waste are discarded annually in Alaska. The simplest way to dispose of t his waste is to discharge it into deep water for the tides to carry it away 0 This is one reason why salmon canneries inAlaska are located on docks over deepwater whenever this is at allpossible. Can neries located near shoal water must cevise other means of disposal. This results in an expense, sometimes rather la.rge, for chu~es, bins, and scows, with which to collect and carry the waste to deep water and away from current s which might return the waste to the beach near the FIG. 1 - HORSE SLAUGHTERING AND FOOD-MIXING PLANT OF A MINK cannery. FARMERSI COOPERATIVE NEAR SALT LAKE r ITY, UTAH. -

WDFW Pacific Salmon and Wildlife

PREFACE This Updated Special Edition Technical Report is a product of the project: Wildlife –Habitat Relationships in Oregon and Washington (Johnson and O’Neil 2001). The integration of the information on the ecology and management of species in terrestrial, freshwater, and marine environs has been a focus of the project since its inception. For the first time, this Special Edition Technical Report synthesizes fundamental and crucial information linking salmon with wildlife species and the broader aquatic and terrestrial realms in which the co-exist. Readers will find this scientifically-robust report to greatly strengthen our collective understanding of the role that salmon play in the population so Pacific Northwest wildlife species, the ecology of freshwater ecosystems, and how management activities such as hatcheries and harvest can impact these aspects. We thank the authors who contributed important time and effort to the making of this report. Efforts on this Special Edition Technical Report have been supported by a large number of entities, including the 34 Project Partners and Contributing Sponsors of Wildlife –Habitat Relationships in Oregon and Wash- ington: Birds of Oregon Project; Birds of Washington Project; Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs; Donavin Leckenby; Environmental Protection Agency – Corvallis Lab.; Federal Highways Administration; Fish and Wildlife Information Exchange; National Fish and Wildlife Foundation; Northwest Power Planning Council; Oregon Cooperative Wildlife Resources Institute; Oregon/Washington Partners in Flight; Pacific States Marine Fish Commission; Quileute Indian Tribe; Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation; Society for Northwestern Vertebrate Biology; USDA Forest Service; USDI Bureau of Land Management;’ USDI Fish and Washington Community, Trade, and Economic Development’; Washington Department of Natural Resources; Washington Department of Transportation; Washington Forest Protection Associa- tion; Weyerhaeuser Company; Wildlife Management Institute. -

SITE of FIRST SALMON CANNERY to BE DEDICATED--April 19, 1964

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR NATIONALPARK SERVICE Evans - 343-5634 FISH ANDW ILDLIFE SERVICE For Release APRIL 19, 1964 SITE OF FIRST SALMONCANNERY TO BE DEDICATED The site of the first Pacific Coast salmon cannery, constructed in Sacramento 100 years ago, will be dedicated asa National Historic Landmark April 28, George B. Hartsog, Jr., Director of the National Park Service, announced today. Senator E. L. Bartlett of Alaska, a member of the Senate Merchant Marine and Fisheries Subcommittee, will be principal speaker. Salmon canners from throughout the Pacific Northwest and Alaska are being invited to attend. Other special guests will include Governor EdmundG. (Pat) Brown and NickBea, President of Peter Pan Seafood Company and a pioneer Alaska and Pacific Northwest salmon canner. Under Secretary of the Interior James K. Carr will participate in the unveiling of a commemorative plaque at the site in a ceremony at 11:30 a.m. Lloyd Turnacliff, prominent in the Sacramento fishing industry and a former vice president of the National Fisheries Institute, will be master of ceremonies. The forerunner of today's multimillion dollar Pacific salmon canning industry was begun in the spring of 1864 by three transplanted Maine fishermen, William and George Hume and Andrew Hapgood. William Hume entered the fishing business in Sacramento in 1852 and was joined by his brother, George, a few years later, The business at first was limited to the sale of fresh and salted salmon. The brothers then persuaded Hapgood, a former schoolmate, to come from Maine to join the enterprise. Hapgood was a fisherman and 8 tinsmith with experience in canning lobster in New England. -

Douglas Deur Empires O the Turning Tide a History of Lewis and F Clark National Historical Park and the Columbia-Pacific Region

A History of Lewis and Clark National and State Historical Parks and the Columbia-Pacific Region Douglas Deur Empires o the Turning Tide A History of Lewis and f Clark National Historical Park and the Columbia-Pacific Region Douglas Deur 2016 With Contributions by Stephen R. Mark, Crater Lake National Park Deborah Confer, University of Washington Rachel Lahoff, Portland State University Members of the Wilkes Expedition, encountering the forests of the Astoria area in 1841. From Wilkes' Narrative (Wilkes 1845). Cover: "Lumbering," one of two murals depicting Oregon industries by artist Carl Morris; funded by the Work Projects Administration Federal Arts Project for the Eugene, Oregon Post Office, the mural was painted in 1942 and installed the following year. Back cover: Top: A ship rounds Cape Disappointment, in a watercolor by British spy Henry Warre in 1845. Image courtesy Oregon Historical Society. Middle: The view from Ecola State Park, looking south. Courtesy M.N. Pierce Photography. Bottom: A Joseph Hume Brand Salmon can label, showing a likeness of Joseph Hume, founder of the first Columbia-Pacific cannery in Knappton, Washington Territory. Image courtesy of Oregon State Archives, Historical Oregon Trademark #113. Cover and book design by Mary Williams Hyde. Fonts used in this book are old map fonts: Cabin, Merriweather and Cardo. Pacific West Region: Social Science Series Publication Number 2016-001 National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior ISBN 978-0-692-42174-1 Table of Contents Foreword: Land and Life in the Columbia-Pacific -

How the Presidents Ate Their Salmon Catherine Schmitt

University of Maine From the SelectedWorks of Catherine Schmitt Winter 2013 How the presidents ate their salmon Catherine Schmitt Available at: https://works.bepress.com/catherine_schmitt/19/ celebrations | catherine schmitt How the Presidents Ate Their Salmon the rivers of the East Coast of North America once were president’s salmon would have been prepared and eaten filled with fish. Alewives, eel, shad, smelt, striped bass, stur- reveals that the celebratory eating of salmon happened at the geon, salmon – each had their season of plenty and associated same time as the decimation of salmon populations and their rituals and habits of preparation and eating. These fish, which associated food traditions. Thus, through the Presidential migrate between coastal rivers and the ocean, sustained Salmon, local anglers maintained cultural traditions of catch- Native American populations and contributed to the survival ing and eating salmon, keeping them in the social memory of of early European colonies. Today, they persist at a fraction the region and nation, while at the same time creating of their former abundance, and several species are consid- a moment that reflected how national policies were affecting ered threatened or endangered. Their history reflects every- local resources. thing humans have done – fishing, logging, damming, and polluting—to diminish the quantity and quality of food pro- vided by coastal rivers. A Tradition Begins The overfishing of New England rivers and bays, the Gulf of Maine, and the North Atlantic Ocean continues to be well In 1912, a Norwegian immigrant, house painter, boat builder, documented.1 Less often told (and more often forgotten) are and fly fisherman named Karl Anderson decided to send the regional stories of abundance and scarcity: the river-by- an Atlantic salmon to the President of the United States. -

Alaska Fisheries: a Guide to History Resources

November 30, 2015 Alaska Fisheries: A Guide to History Resources Prepared by the Alaska Historical Society’s Alaska Historic Canneries Initiative Compiled by Robert W. King, September 2015 Dedication This guide to the history resources of Alaska fisheries is dedicated to Wrangell historian Patricia “Pat” Ann Roppel (1938‐2015). Pat moved to Alaska in 1959 and wrote thirteen books and hundreds of articles, many about the history of Alaska fisheries, including Alaska Salmon Hatcheries and Salmon from Kodiak. Twice honored as Alaska Historian of the Year, Pat Roppel is remembered for the joy she took in research and writing, her support of fellow historians and local museums, and her enthusiasm and good humor. Alaska Historic Canneries Initiative The Alaska Historic Canneries Initiative was created in 2014 to document, preserve, and celebrate the history of Alaska's commercial fish processing plants, and better understand the role the seafood industry played in the growth and development of our state. Alaska boasts some of largest and best‐managed fisheries in the world. The state currently produces over 5 billion pounds of seafood products annually worth over $5 billion to its fishermen and even more on the wholesale and retail markets. Fisheries are closely regulated by state and federal authorities, and while fish populations naturally fluctuate, no commercially harvested species are being overfished. Canneries are central to the development of Alaska, but an overlooked and neglected part of our historic landscape. Only two Alaska canneries are listed on the National Register of Historic Places, although few historic resources have impacted Alaska’s economy and history as greatly.