Immigrant Labor in Fish Processing in the Pacific Northwest and British Columbia and Current Undocumented Labor Adi D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COUNTRY SECTION United States Fishery Products

Validity date from COUNTRY United States 22/01/2021 00499 SECTION Fishery products Date of publication 28/07/2007 List in force Approval number Name City Regions Activities Remark Date of request 1000025102 GET SEAFOOD, INC. Winter Haven Florida PP 08/04/2013 1000025909 Fagan Alligator Products, Inc. Dade City Florida PP 1000084596 Sea-Trek Enterprises, Inc. East Greenwich Rhode Island PP O! 10/07/2008 1000112376 Pontchartrain Blue Crab Slidell Louisiana PP 14/04/2010 1000113172 Fishermen's Ice & Bait, Inc. Madeira Beach Florida PP 1000113708 Beck's Smokery Pompano Beach Florida PP 1000113902 Colorado Boxed Beef Co. Port Everglades Florida CS 16/11/2011 1000114005 D & D Seafood Corporation Marathon Florida PP 1000114027 BAMA SEA PRODUCTS St. Petersburg Florida PP 1000114048 Moon's Seafood Company W. Melbourne Florida PP O! 1000114049 Glanbia Performance Nutrition (Manufacturing), Inc., Florida Sunrise Florida PP 13/10/2017 Facility 1000114069 Placeres & Sons Seafood Hialeah Florida PP 1000114070 Webb's Seafood, Inc. Youngstown Florida PP 14/10/2009 1000114156 Cox's Wholesale Seafood, Inc. Tampa Florida PP 1000114170 Kings Seafood, Inc. Port Orange Florida PP 1 / 59 List in force Approval number Name City Regions Activities Remark Date of request 1000114326 Optimus, Inc. Dba Marky's Miami Florida PP 1000115645 AMERIQUAL FOODS LLC Evansville Indiana PP 06/02/2019 1000115810 Henriksen Fisheries, Inc Sister Bay Wisconsin PP 1000117125 RB Manufacturing LLC Salt Lake City Utah PP 08/01/2015 1000120312 Stauber Performance Ingredients, Inc. Florida New York PP 08/08/2019 1000120556 Plenus Group, Inc. Lowell Massachusetts PP 06/05/2008 1000120753 GARBO LOBSTER LLC Groton Connecticut PP 17/10/2016 1000121950 True World Foods, NY LLC Elizabeth New Jersey PP Aq 1000122358 Lamonica Fine Foods, Inc. -

Trends in the Utilization and Production of Seafood Byproducts

Advances in Seafood Byproducts 351 Alaska Sea Grant College Program • AK-SG-03-01, 2003 Trends in the Utilization and Production of Seafood Byproducts Hans Nissen Atlas-Stord, Inc., Kansas City, Missouri Abstract Seafood companies in the North Pacific and Alaska generate a significant volume of seafood byproducts and could benefit environmentally and economically by utilizing these byproducts. Today many of the compa- nies have integrated a fish meal plant to process seafood byproduct into valuable high quality fish meal and oil which is sold worldwide in com- petition with other protein meals. In order to justify the investment in a production facility to utilize the byproduct the annual volume must be considered. The trend has been to combine the byproduct from various plants in order to have enough volume to make the operation feasible. In Alaska with many small processors at remote locations this can be a difficult task, and the reason much of the seafood byproduct today is still being dumped or disposed at landfills. We have considered a pro- cess where the byproduct is collected at the different sites and brought to a central location where it is hydrolyzed into silage and dried using a carrier liquid drying process (CLD) producing a stable product that can be marketed worldwide. Introduction As a fish meal equipment manufacturer we are in many cases the first in line to get the call when a fish processor, for various reasons, must con- sider how to utilize the fish byproduct from his process. The reasons can include new environmental regulations regarding disposal of byproduct, or an increase in disposal cost from the local landfill or from the person who hauls the byproduct away. -

Vocational Education and Fisheries S, N. Dwivedi & V. Ravindranathan

Vocational education and fisheries Item Type article Authors Dwivedi, S.N.; Ravindranathan, V. Download date 24/09/2021 18:45:18 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/31676 Journal of the Indian Fisheries Association 8+9, 1978-79, 65-70 VOCATIONAL EDUCATION AND FISHERIES S, N. DWIVEDI & V. RAVINDRANATHAN Central Institute of Fisheries Education Versova, Bombay-400 067. ABSTRACT The knowledge and skill of the poople are important tools for the development of natural resources and for the prosperty of any country. The quality of education is judged not only from the inquistiveness and knowiedge it can impart but also from it's usefulees in meeting the urgent economic problems of the country. Vocational Courses in fisheries are offered in four states. The technologies in fisheries developed offer good scope for Vocational training for self employment. There is an urgent need to have radical revision of the course content to make the students vocationaliy competent. FISHERIES EDUCATION — STATE OF ART : Recognising the need to study, assess and develop the fishery resources of the country, Govt. of India established the Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute (CMFRI) Cochin; Central Inland Fisheries Risearch Institute (CIFRI) Barrackpore, Central Institute of Fisheries Technology (CIFI) Cochin and Deep Sea Fishing Station, Bombay soon after the Independence. Since then, the fish production trend in the country has been encouraing. The annual fish production has increased from 0.5 million tons in 1950, to 2.6 million tons in 1983. Although the rate of increase has been fairly good, the per capita consumption of fish, even now, is less than 5 kg/yr. -

Alaska Park Science 19(1): Arctic Alaska Are Living at the Species’ Northern-Most to Identify Habitats Most Frequented by Bears and 4-9

National Park Service US Department of the Interior Alaska Park Science Region 11, Alaska Below the Surface Fish and Our Changing Underwater World Volume 19, Issue 1 Noatak National Preserve Cape Krusenstern Gates of the Arctic Alaska Park Science National Monument National Park and Preserve Kobuk Valley Volume 19, Issue 1 National Park June 2020 Bering Land Bridge Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve National Preserve Denali National Wrangell-St Elias National Editorial Board: Park and Preserve Park and Preserve Leigh Welling Debora Cooper Grant Hilderbrand Klondike Gold Rush Jim Lawler Lake Clark National National Historical Park Jennifer Pederson Weinberger Park and Preserve Guest Editor: Carol Ann Woody Kenai Fjords Managing Editor: Nina Chambers Katmai National Glacier Bay National National Park Design: Nina Chambers Park and Preserve Park and Preserve Sitka National A special thanks to Sarah Apsens for her diligent Historical Park efforts in assembling articles for this issue. Her Aniakchak National efforts helped make this issue possible. Monument and Preserve Alaska Park Science is the semi-annual science journal of the National Park Service Alaska Region. Each issue highlights research and scholarship important to the stewardship of Alaska’s parks. Publication in Alaska Park Science does not signify that the contents reflect the views or policies of the National Park Service, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute National Park Service endorsement or recommendation. Alaska Park Science is found online at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/alaskaparkscience/index.htm Table of Contents Below the Surface: Fish and Our Changing Environmental DNA: An Emerging Tool for Permafrost Carbon in Stream Food Webs of Underwater World Understanding Aquatic Biodiversity Arctic Alaska C. -

Innovation Management in Seafood Industry Sector

Development of Innovation Capabilities in the New Zealand Seafood Industry Sector Andrew Jeffs Principal Scientist, National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research, P.O. Box 109-695, Auckland, New Zealand Email: [email protected] Shantha Liyanage Associate Professor, Business School, The University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, Auckland, New Zealand Email: [email protected] Abstract: Most seafood industries around the world are founded on wild capture fisheries which have been facing a static or declining resource base due to over exploitation. Achieving growth with this restraint is a challenge that seafood enterprises have struggled with globally for more than 20 years. Innovation efforts in this industry have focused on developing new sources of raw material, increasing financial returns through value-adding, increased efficiency of production and management integration. An early change in the management regime for wild fish stocks is identified as the key factor in encouraging innovation in the New Zealand seafood industry. The greater certainty in raw material supply provided by the management regime has enabled seafood enterprises to shift their attention from competing to secure sufficient raw material toward increasing their returns from the raw materials they know will be available to them. This paper examines the dynamics of innovation capability building and provides management directions for enhancing innovation capability in this industry. Overall, it is hoped that this study may help to act as an exemplar for encouraging innovation in other national or regional seafood industries, and for other industries based on renewable natural resources. Keywords: seafood; innovation; Quota Management System; innovation capability, New Zealand; aquaculture; biotechnology; national innovation system. -

Refashioning Production in Bristol Bay, Alaska by Karen E. Hébert A

Wild Dreams: Refashioning Production in Bristol Bay, Alaska by Karen E. Hébert A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in the University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Professor Fernando Coronil, Chair Associate Professor Arun Agrawal Associate Professor Stuart A. Kirsch Associate Professor Barbra A. Meek © Karen E. Hébert 2008 Acknowledgments At a cocktail party after an academic conference not long ago, I found myself in conversation with another anthropologist who had attended my paper presentation earlier that day. He told me that he had been fascinated to learn that something as “mundane” as salmon could be linked to so many important sociocultural processes. Mundane? My head spun with confusion as I tried to reciprocate chatty pleasantries. How could anyone conceive of salmon as “mundane”? I was so confused by the mere suggestion that any chance of probing his comment further passed me by. As I drifted away from the conversation, it occurred to me that a great many people probably deem salmon as mundane as any other food product, even if they may consider Alaskan salmon fishing a bit more exotic. At that moment, I realized that I was the one who carried with me a particularly pronounced sense of salmon’s significance—one that I shared with, and no doubt learned from, the people with whom I conducted research. The cocktail-party exchange made clear to me how much I had thoroughly adopted some of the very assumptions I had set out simply to study. It also made me smile, because it revealed how successful those I got to know during my fieldwork had been in transforming me from an observer into something more of a participant. -

Critique of PPI Study on Shale Gas Job Creation Prepared by Jannette M

Critique of PPI Study on Shale Gas Job Creation Prepared by Jannette M. Barth, Ph.D. Pepacton Institute LLC January 2, 2012 Supporters of shale gas drilling in New York State frequently reference a report issued by The Public Policy Institute of New York State, Inc. (PPI) titled “Drilling for Jobs: What the Marcellus Shale Could Mean for New York,” July 2011. As with the other industry-funded studies on this subject, this PPI report is one- sided and self-evidently crafted with the sole purpose of supporting the gas industry. Independent academic research not funded by the gas industry reaches vastly different conclusions than do these industry-funded studies. The PPI report does not mention the independent research. Some examples of conclusions made by independent researchers are that areas that once had thriving extractive industries end up suffering the highest rates of long-term poverty (Freudenburg and Wilson); and counties that have focused on energy development underperform economically compared to peer counties with little or no energy development (Headwaters Economics). Independently researched studies include the following: • “Fossil Fuel Extraction as a County Economic Development Strategy: Are Energy-focusing Counties Benefiting?”, Headwaters Economics, September 2008 (Revised 7/11/09). • “Mining the Data: Analyzing the Economic Implications of Mining for Nonmetropolitan Regions,” William R. Freudenberg and Lisa J. Wilson, Sociological Inquiry, Vol. 72, Fall 2002, 549-75. • “The Economic Impact of Shale Gas Extraction: A Review of Existing Studies,” Thomas C. Kinnaman, Ecological Economics, 70 (2011) 1243-1249. • “Hydrofracking a Boom-Bust Endeavor,” Susan Christopherson, August 14, 2011. • “The Local Economic Impacts of Natural Gas Development in the Valle Vidal, New Mexico,” Thomas Michael Power, January 2005. -

Technological Modernization and Its Impact on Agriculture, Fisheries And

Publications 2017 Technological Modernization and Its Impact on Agriculture, Fisheries and Fossil Fuel Utilization in the Asia Pacific Countries with Emphasis on Sustainability Perspective Rajee Olaganathan Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, [email protected] Kathleen Quigley Embry Riddle Aeronautical University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.erau.edu/publication Part of the Agriculture Commons, Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, Oil, Gas, and Energy Commons, and the Sustainability Commons Scholarly Commons Citation Olaganathan, R., & Quigley, K. (2017). Technological Modernization and Its Impact on Agriculture, Fisheries and Fossil Fuel Utilization in the Asia Pacific Countries with Emphasis on Sustainability Perspective. International Journal of Advanced Biotechnology and Research (IJBR), 8(2). Retrieved from https://commons.erau.edu/publication/839 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. International Journal of Advanced Biotechnology and Research (IJBR) ISSN 0976-2612, Online ISSN 2278–599X, Vol-8, Issue-2, 2017, pp422-441 http://www.bipublication.com Research Article Technological modernization and its impact on Agriculture, Fisheries and Fossil fuel utilization in the Asia Pacific Countries with emphasis on sustainability perspective Olaganathan Rajee* and Kathleen Quigley College of Arts and Sciences and College of Business Embry Riddle Aeronautical University Worldwide, 75 Bukit Timah Road, #02-01/02 Boon Siew Building, Singapore. 229833 * Corresponding Author E-mail: [email protected]; Phone: +1 626 236 2254 ABSTRACT Modernization is a process that moves towards efficiency. This affects most of the fields such as agriculture, fisheries, forestry, urban planning, policy, fossil fuel usage, manufacturing, technology, economic growth etc. -

Challenges and Opportunities of the US Fishing Industry

Advancing Opportunity, Prosperity, and Growth WWW.HAMILTONPROJECT.ORG What’s the Catch? Challenges and Opportunities of the U.S. Fishing Industry By Melissa S. Kearney, Benjamin H. Harris, Brad Hershbein, David Boddy, Lucie Parker, and Katherine Di Lucido SEPTEMBER 2014 he economic importance of the fishing sector extends well beyond the coastal communities for which it is a vital industry. Commercial fishing operations, including seafood wholesalers, processors, and retailers, all contribute billions of dollars annually to the U.S. economy. Recreational fishing— Temploying both fishing guides and manufacturers of fishing equipment—is a major industry in the Gulf Coast and South Atlantic. Estimates suggest that the economic contribution of the U.S. fishing industry is nearly $90 billion annually, and supports over one and a half million jobs (National Marine Fisheries Service [NMFS] 2014). A host of challenges threaten fishing’s viability as an American industry. Resource management, in particular, is a key concern facing U.S. fisheries. Since fish are a shared natural resource, fisheries face traditional “tragedy of the commons” challenges in which the ineffective management of the resource can result in its depletion. In the United States, advances in ocean fishery management over the past four decades have led to improved sustainability, but more remains to be done: 17 percent of U.S. fisheries are classified as overfished (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration [NOAA] 2014), and even those with adequate fish stocks may benefit economically from more-efficient management structures. Meeting the resource management challenge can lead to improved economic activity and better sustainability in the future. -

An Ethnography of Old Harbor and Ouzinkie, Alaska

BLACK DUCKS AND SALMON BELLIES An Ethnography of Old Harbor and Ouzinkie, Alaska by Craig Mishler Technical Memorandum No. 7 A Report Produced for the U.S. Minerals Management Service Cooperative Agreement 14-35-0001-30788 March 2001 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Subsistence 333 Raspberry Road Anchorage, Alaska 99518 This report has been reviewed by the Minerals Management Service and approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Service, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. ADA PUBLICATIONS STATEMENT The Alaska Department of Fish and Game operates all of its public programs and activities free from discrimination on the basis of sex, color, race, religion, national origin, age, marital status, pregnancy, parenthood, or disability. For information on alternative formats available for this and other department publications, please contact the department ADA Coordinator at (voice) 907- 465-4120, (TDD) 1-800-478-3548 or (fax) 907-586-6595. Any person who believes she or he has been discriminated against should write to: Alaska Department of Fish and Game PO Box 25526 Juneau, AK 99802-5526 or O.E.O. U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 20240 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ...............................................................................................................................iii List of Figures ...............................................................................................................................iii -

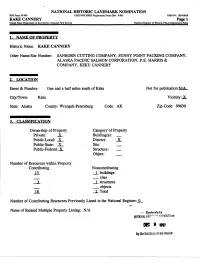

KAKE CANNERY Other Name/Site Number

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 KAKE CANNERY Page 1 United Sates Department of the Interior. National Park Service_______________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: KAKE CANNERY Other Name/Site Number: SANBORN CUTTING COMPANY, SUNNY POINT PACKING COMPANY, ALASKA PACIFIC SALMON CORPORATION, P.E. HARRIS & COMPANY, KEKU CANNERY 2. LOCATION Street & Number: One and a half miles south of Kake Not for publication:MZA_ City/Town: Kake Vicinity :_X_ State: Alaska County: Wrangell-Petersburg Code: AK Zip Code: 99830 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): _ Public-Local: X District: JL Public-State: X Site: _ Public-Federal:_X_ Structure: _ Object: _ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 15 _L buildings _ _ sites _ 2_ ... 1 structures _ _ objects 18 JL Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: JL_ Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A - n of at 4 a D6D 0 by the Secretary of the Intsrior NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) 0MB No. 1024-OMg KAKE CANNERY Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Pom 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

POTENTIAL MARKETS for ALASKA SALMON CANNERY WASTE by Norman B

August 1952 COMMERCIAL FISHERIES REVIEW 5 POTENTIAL MARKETS FOR ALASKA SALMON CANNERY WASTE By Norman B. Wigutoff- INTROOUCfrON Since the beginning of salmon canning in Alaska late in the nineteenth cen tury, waste disposal or utilization has been a problem. The canning process re sults in the use of only two-thirds of the whole fish. The other one-third- head, tail, fins, and viscera or entrails--is discarded. Although reduction plants are successfully operated in areas of Alaska where large volumes of waste are available froll! several canneries, it has proved im practical with present costs to operate the usual type of reduction plant inareas where only one or tvlO canneries are located. Inasmuch as many canneries are lo cated in isolated places, the problem of waste utilization in these areas remains. Between 100,000,000 and 125,000,000 pounds of salmon waste are discarded annually in Alaska. The simplest way to dispose of t his waste is to discharge it into deep water for the tides to carry it away 0 This is one reason why salmon canneries inAlaska are located on docks over deepwater whenever this is at allpossible. Can neries located near shoal water must cevise other means of disposal. This results in an expense, sometimes rather la.rge, for chu~es, bins, and scows, with which to collect and carry the waste to deep water and away from current s which might return the waste to the beach near the FIG. 1 - HORSE SLAUGHTERING AND FOOD-MIXING PLANT OF A MINK cannery. FARMERSI COOPERATIVE NEAR SALT LAKE r ITY, UTAH.