The Asian Conventional Military Balance in 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Assembly Distr.: General 31 July 2001 English Original: Arabic/English/French/ Russian/Spanish

United Nations A/56/257 General Assembly Distr.: General 31 July 2001 English Original: Arabic/English/French/ Russian/Spanish Fifty-sixth session Item 85 (s) of the provisional agenda* General and complete disarmament: transparency in armaments United Nations Register of Conventional Arms Report of the Secretary-General** Contents Paragraphs Page I. Introduction .......................................................... 1–10 2 II. Information received from Governments................................... 11–12 4 A. Composite table of replies of Governments ...................................... 5 B. Replies received from Governments ............................................ 8 III. Index of background information provided by Governments for the calendar year 2000 ...... 60 IV. Information received from Governments on military holdings and procurement through national production .............................................................. 63 Annex Views received from Governments in accordance with paragraph 5 (a) of General Assembly resolution 55/33 U .............................................................. 103 * A/56/150. ** Finalization of the present report was dependent on the receipt of a substantial number of submissions by Governments. 01-49573 (E) 200901 *0149573* A/56/257 I. Introduction 1. In accordance with General Assembly resolution 46/36 L of 9 December 1991, on transparency in armaments, the Secretary-General, on 1 January 1992, established the United Nations Register of Conventional Arms. In that resolution, the -

Canada Gouvernementaux Canada

Public Works and Government Services Travaux publics et Services 1 1 Canada gouvernementaux Canada RETURN BIDS TO: Title - Sujet RETOURNER LES SOUMISSIONS À: SIMULATION ENTITY MODELS Bid Receiving - PWGSC / Réception des soumissions Solicitation No. - N° de l'invitation Amendment No. - N° modif. - TPSGC W8475-135211/B 006 11 Laurier St. / 11, rue Laurier Client Reference No. - N° de référence du client Date Place du Portage, Phase III Core 0A1 / Noyau 0A1 W8475-135211 2014-03-20 Gatineau GETS Reference No. - N° de référence de SEAG Quebec PW-$$EE-048-26597 K1A 0S5 Bid Fax: (819) 997-9776 File No. - N° de dossier CCC No./N° CCC - FMS No./N° VME 048ee.W8475-135211 Time Zone SOLICITATION AMENDMENT Solicitation Closes - L'invitation prend fin at - à 02:00 PM Fuseau horaire MODIFICATION DE L'INVITATION Eastern Daylight Saving on - le 2014-04-25 Time EDT F.O.B. - F.A.B. The referenced document is hereby revised; unless otherwise indicated, all other terms and conditions of the Solicitation Plant-Usine: Destination: Other-Autre: remain the same. Address Enquiries to: - Adresser toutes questions à: Buyer Id - Id de l'acheteur Friesen, Manon 048ee Ce document est par la présente révisé; sauf indication contraire, Telephone No. - N° de téléphone FAX No. - N° de FAX les modalités de l'invitation demeurent les mêmes. (819) 956-1161 ( ) ( ) - Destination - of Goods, Services, and Construction: Destination - des biens, services et construction: Comments - Commentaires Vendor/Firm Name and Address Instructions: See Herein Raison sociale et adresse du fournisseur/de l'entrepreneur Instructions: Voir aux présentes Delivery Required - Livraison exigée Delivery Offered - Livraison proposée Vendor/Firm Name and Address Raison sociale et adresse du fournisseur/de l'entrepreneur Issuing Office - Bureau de distribution Telephone No. -

World of Wheels Country Entry

BELGIUM Flag description: three equal vertical bands of black (hoist side), yellow, and red note: the design was based on the flag of France. Background: Belgium became independent from the Neth- erlands in 1830; it was occupied by Germany during World Wars I and II. It has prospered in the past half century as a modern, technologically advanced European state and mem- ber of NATO and the EU. Tensions between the Dutch- speaking Flemish of the north and the French-speaking Wal- loon of the south have led in recent years to constitutional amendments granting these regions formal recognition and autonomy. Geography Belgium. Location: Western Europe, bordering the North Sea, between France and the Netherlands. Area: total: 30,528 sq. km. Area - comparative: about the size of Maryland. Land boundaries: total: 1,385 km. Border coun- tries: France 620 km, Germany 167 km, Luxembourg 148 km, Netherlands 450 km. Coastline: 66.5 km. Climate: tem- perate; mild winters, cool summers; rainy, humid, cloudy. Terrain: flat coastal plains in northwest, central rolling hills, rugged mountains of Ardennes Forest in southeast. Natural resources: construction materials, silica sand, carbonate. Natural hazards: flooding is a threat along rivers and in areas of reclaimed coastal land, protected from the sea by concrete dikes. Environment - current issues: the environment is exposed to intense pressures from human activities: urbanization, dense transportation network, industry, extensive anim- al breeding and crop cultivation; air and water pollution also have repercussions for neighboring coun- tries; uncertainties regarding federal and regional responsibilities (now resolved) have slowed pro- gress in tackling environmental challenges. -

Assemblée Générale Distr

Nations Unies A/65/133 Assemblée générale Distr. générale 15 juillet 2010 Français Original : anglais/arabe/espagnol/ français/russe Soixante-cinquième session Point 99 bb) de l’ordre du jour provisoire* Désarmement général et complet : transparence dans le domaine des armements Registre des armes classiques Rapport du Secrétaire général Résumé Le présent rapport rassemble les informations communiquées par les États Membres sur l’exportation et l’importation des armes classiques visées par le Registre des armes classiques, ainsi que des informations générales sur les dotations militaires, les achats liés à la production nationale et les transferts internationaux d’armes légères et de petit calibre pour l’année civile 2009. À la date du présent rapport, le Secrétaire général avait reçu les rapports de 51 gouvernements. * A/65/150. 10-45299 (F) 160810 180810 *1045299* A/65/133 Table des matières Paragraphes Page I. Introduction ......................................................... 1–3 3 II. Informations communiquées par les gouvernements ........................ 4–5 3 A. Tableau synoptique des informations communiquées par les gouvernements .......... 4 B. Réponses reçues des gouvernements sur les transferts d’armes classiques ............ 7 III. Informations communiquées par les gouvernements sur les dotations militaires et les achats liés à la production nationale .......................................... 36 IV. Informations communiquées par les gouvernements sur les transferts internationaux d’armes légères et de petit calibre ................................................. 64 Annexe Vues exprimées par les gouvernements conformément au paragraphe 6 a) et b) de la résolution 64/54 de l’Assemblée générale ...................................... 127 2 10-45299 A/65/133 I. Introduction 1. Le présent rapport est le dix-huitième rapport de synthèse publié par le Secrétaire général depuis la création du Registre des armes classiques1. -

Wheeled Apcs

Wheeled APCs WHEELED ARMORED PERSONNEL CARRIERS Australian Wheeled APCs Austrian Wheeled APCs Belgian Wheeled APCs Brazilian Wheeled APCs British Wheeled APCs Canadian Wheeled APCs Chilean Wheeled APCs Chinese Wheeled APCs Croatian Wheeled APCs Czech Wheeled APCs Dutch Wheeled APCs Egyptian Wheeled APCs Finnish Wheeled APCs French Wheeled APCs German Wheeled APCs Guatemalan Wheeled APCs Hungarian Wheeled APCs Indian Wheeled APCs International Wheeled APCs Irish Wheeled APCs Israeli Wheeled APCs Italian Wheeled APCs Japanese Wheeled APCs Mexican Wheeled APCs North Korean Wheeled APCs Portuguese Wheeled APCs Romanian Wheeled APCs Russian Wheeled APCs Salvadoran Wheeled APCs Saudi Wheeled APCs Slovakian Wheeled APCs South African Wheeled APCs Spanish Wheeled APCs Swedish Wheeled APCs Swiss Wheeled APCs Turkish Wheeled APCs Ukrainian Wheeled APCs US Wheeled APCs Yugoslavian Wheeled APCs file:///E/My%20Webs/misc_pages/armored_personnel_carriers_3.html[3/22/2020 5:55:29 PM] Australian Wheeled APCs ADI/Thales Australia Bushmaster Notes: The Bushmaster Protected Mobility Vehicle was designed as a successor to the S-600, under the Bushranger Infantry Mobility Vehicle competition; it eventually emerged as the winner of that competition, with development beginning in 1998. The development and testing process was long, incloved, and troubled, and deliveries did not begin until 2005. The Bushmaster is based on a design originally conceived by the Irish company of Timoney; considerable portions of the Bushmaster are therefore manufactured under a licensing agreement with Timoney, though production is undertaken wholly in Australia. ADI began the part of the design process done in Australia, but production later passed to Thales Australia, who also developed several variants. (Virtually all of these variants differ primarily in internal arrangements and equipment; externally, almost all of the different versions differ little from each other.) The primary users of the Bushmaster are the Australian Army and Air Force, but it is also used by the Dutch Army and British Army. -

SP's Land Forces April-May 2011

April-May 2011 Volume 8 No 2 R `100.00 (India-based Buyer Only) SP’s AN SP GUIDE PUBLICATION WWW.SPSLANDFORCES.NET ROUNDUP IN THIS ISSUE The ONLY journal in Asia dedicated to Land Forces PAGE 4 >> COVER STORY Future Trends To be successful in a full spectrum conflict, there is a need to modernise, have a balanced profile and upgrade our defence ‘Modernisation would depend on industry to achieve a reasonable degree of indigenisation thereby enhancing our capabilities in a two-front war. the pace of acquisition of guns and Major General P.K. Chakravorty PAGE 6 financial outlays provided for induction’ Safe, Secure & Reliable The project for TCS for the Indian Army has PHOTOGRAPHS : SP Guide Pubns been undertaken under the “Make Procedure” category. TCS is expected to become operational by 2014. Lt General (Retd) V.K. Kapoor PAGE 7 Defence Allocation Up, GDP Share Down This year’s defence budget allocation represents an 11.59 per cent growth over the previous year’s budget. It is only 1.83 per cent of the GDP, while last year, the defence budget was 2.12 per cent of the GDP. Lt General (Retd) V.K. Kapoor PAGE 8 China’s Rising Defence Budget Cause for Alarm At a time when China’s ambition for power projection has considerably increased, a double-digit growth in China’s defence budget promises to impact adversely the regional security dynamics. Sanjay Kumar PAGE 10 Making Every Mission Possible A common platform for a light armoured vehicle (wheeled) which could fulfill the role Artillery constitutes a major war-winning component of the Indian Army and of all the functions required to be carried out in conventional and asymmetric conflicts has performed brilliantly in every conflict fought by the Indian Army since would be desirable. -

ADF Capability Snapshot 2015: Army

STRATEGIC STRATEGIC INSIGHTS ADF capability snapshot 2015 Part 3—Army 100 Andrew Davies This paper surveys the capabilities of the Australian Army and is an update of previous reviews in 2008 and 2010. Other papers in this series update the corresponding reports on Royal Australian Air Force, Royal Australian Navy and a future paper will examine C4ISR (command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance) capabilities. Army capability summary The main focus of the Australian Army over the past 15 years has been on sustaining combat, training, stabilisation and peacekeeping operations in our near region and the Middle East and Afghanistan theatres. The demands of the ADF’s operational tempo have driven a major rethinking of the structure of the Army under Plan Beersheba. Now well advanced, the end state will be three essentially similar brigades, which will make rotational deployments easier to manage and sustain. Like the RAAF and the RAN, described in previous reports in this series, the Army needs a major recapitalisation of its equipment. An ASLAV (Australian Light Armoured Vehicle) fires on a target at Puckapunyal training area during Exercise Chong Ju, a live-fire training exercise by the Combined Arms Training Centre, on 21 October 2015. Photo courtesy Department of Defence. November 2015 2 ADF capability snapshot 2015: Part 3—Army The replacement of the Army’s fleet of vehicles is now underway. The requirement for protected mobility for deployed forces has increased as the sophistication and capabilities of both contemporary militaries and non-state actors have increased. Soft-skinned vehicles are particularly vulnerable to even small improvised explosive devices (IEDs). -

M123 5-Ton Truck with M113 Hull Middleton

Issue Period Nationality Text Plan Scale Subject Author 39.4 M US Y 'Alabama Slammer' M123 5-ton truck with M113 hull Middleton 31.6 M Israeli Y Y 48 'Sandwich truck' on CMP chassis Sadler 28.5 M Russian Y 'Swamp Tank' Obiekt 279 Fleming 22.3 WW2 US Y 76 0.5 ton public address van Clarke 42.2 WW2 Canadian Y 1 Canadian Centaur Battery RCA Middleton 27.2 Y 1/72 kits suitable for 1/76 models Burrows 35.1 Y 1/87 scale models resource list part 1 Ellis 35.2 Y 1/87 scale models resource list part 2 Ellis 35.3 Y 1/87 scale models resource list part 3 Ellis 35.4 Y 1/87 scale models resource list part 4 Ellis 34.3 WW2 German Y Y 38 10.5cm FH 18/3 auf Gefechtswagen 39 (f) Baumann/Dijkhuis 32.6 WW2 German Y Y 76 10.5cm Fh 18/3 auf GW39(H) (f) Baumann/Dijkhuis 3.3 WW2 German Y Y 76 10.5cm LeFh 18 Auld 7.6 WW2 German Y Y 76 10.5cm LeFh 18 Dooley 14.3 WW2 German Y Y 76 10.5cm LeFh 18 auf Char B2 (f) Rue 14.4 WW2 German Y Y 76 10.5cm LeFh 18/1 (Sf) auf GWIVb Sdkfz165/1 Rue 16.3 WW2 German Y Y 76 10.5cm LeFh18 auf CW Lorraine Schlepper F Rue 40.1 WW1 German Y Y 76 10.5cm lFH 98/09 Dijkhuis 40.1 WW1 German Y Y 76 10.5cm M14 1FH Skoda Dijkhuis 23.4 WW2 German Y Y 72 10.5cm Mittlerer Einheitswaffentrager auf Pzkpfw 38(t) Crutchley 53.3 1917-45 USSR Y . -

Project LAND 400: Defining the Army 126

STRATEGIC STRATEGIC INSIGHTS Project LAND 400: defining the army 126 Ben Coleman Spend enough time in a queue for coffee at Defence’s Russell Offices and you’re sure to hear some Army folk complaining about how the land forces are chronically short-changed for modern equipment compared to the Air Force and Navy. But a glance at Chapter 6 of the 2016 Integrated Investment Program shows that they’ll need to find something else to grizzle about.1 Defence’s most comprehensive, and expensive, package of land force modernisation is underway, at a cost of $50–70 billion.2 Nine complementary programs cover every area of land warfare, from personal equipment for the soldiers through to unmanned aerial vehicles, amphibious craft, special forces helicopters, digital networks, surface-to-air missiles and long-range battlefield rocket systems. Moreover, those programs are in addition to Navy and Air Force projects, such as sea and air lift, that directly support the land force. Among these programmatic riches, the jewel in the crown is Project Land 400, through which Defence intends to replace the Army’s fleets of armoured cavalry vehicles (ASLAVs) and M113 armoured personnel carriers (APCs). According to Defence, the project will deliver the Army’s next generation of armoured fighting vehicles, with the firepower, protection and mobility to defeat increasingly lethal and adaptive adversaries well into the future. A BAE Systems Australia Patria AMV35 (left) and a Rheinmetall Boxer CRV (right) drive through the armoured fighting vehicle field firing training area at Puckapunyal Range, Victoria, while participating in the Land 400 risk mitigation activity on 22 February 2017 © Images courtesy Australian Department of Defence. -

Upgrade to Army Armour Fleet

Upgrade to Army armour fleet Australia has chosen the Abrams M1A1 Main Battle Tank as its replacement for the 30-year old The recent Defence Capability whole issue into focus. Leopard 1, which no longer has the firepower nor the force Review has endorsed in principle What direction should Australia be protection capability for modern the provision of replacement tanks taking in provisioning the Army land warfare. for the Army’s Leopard I fleet, the with armour over coming decades? replacement since publicly The key questions revolve around announced to be an M1 Abrams the style of combat and the type of variant. Since the campaign in Iraq, terrain on which the Army will armour has again become an issue have to fight. Will it be the open for land forces as, increasingly, terrain of Middle Eastern deserts or armies confront the realities of 21st Asian lowlands and steppes; will it Century urban combat. be the complex forested and jungle The long running and bitter terrain of the Asia-Pacific and argument in the US over the force northern Australia; or will it be structure for light and highly complex urban terrain found deployable army forces brings this globally? 2 DefenceTODAY magazine DefenceTODAY magazine 3 infantry assaults – remain the most frequent Changing role roles of the modern tank. Mobility and * High strategic mobility to permit rapid protection for infantry have seen armoured global and regional deployment by airlift personnel carriers dominate build numbers and regionally of armour in armoured vehicles since 1940. by sealift. Tanks and armoured vehicles remain the The Battle of Bulge set the trend for the This favours backbone of mechanised land manoeuvre latter half of the last century. -

Acronimos Automotriz

ACRONIMOS AUTOMOTRIZ 0LEV 1AX 1BBL 1BC 1DOF 1HP 1MR 1OHC 1SR 1STR 1TT 1WD 1ZYL 12HOS 2AT 2AV 2AX 2BBL 2BC 2CAM 2CE 2CEO 2CO 2CT 2CV 2CVC 2CW 2DFB 2DH 2DOF 2DP 2DR 2DS 2DV 2DW 2F2F 2GR 2K1 2LH 2LR 2MH 2MHEV 2NH 2OHC 2OHV 2RA 2RM 2RV 2SE 2SF 2SLB 2SO 2SPD 2SR 2SRB 2STR 2TBO 2TP 2TT 2VPC 2WB 2WD 2WLTL 2WS 2WTL 2WV 2ZYL 24HLM 24HN 24HOD 24HRS 3AV 3AX 3BL 3CC 3CE 3CV 3DCC 3DD 3DHB 3DOF 3DR 3DS 3DV 3DW 3GR 3GT 3LH 3LR 3MA 3PB 3PH 3PSB 3PT 3SK 3ST 3STR 3TBO 3VPC 3WC 3WCC 3WD 3WEV 3WH 3WP 3WS 3WT 3WV 3ZYL 4ABS 4ADT 4AT 4AV 4AX 4BBL 4CE 4CL 4CLT 4CV 4DC 4DH 4DR 4DS 4DSC 4DV 4DW 4EAT 4ECT 4ETC 4ETS 4EW 4FV 4GA 4GR 4HLC 4LF 4LH 4LLC 4LR 4LS 4MT 4RA 4RD 4RM 4RT 4SE 4SLB 4SPD 4SRB 4SS 4ST 4STR 4TB 4VPC 4WA 4WABS 4WAL 4WAS 4WB 4WC 4WD 4WDA 4WDB 4WDC 4WDO 4WDR 4WIS 4WOTY 4WS 4WV 4WW 4X2 4X4 4ZYL 5AT 5DHB 5DR 5DS 5DSB 5DV 5DW 5GA 5GR 5MAN 5MT 5SS 5ST 5STR 5VPC 5WC 5WD 5WH 5ZYL 6AT 6CE 6CL 6CM 6DOF 6DR 6GA 6HSP 6MAN 6MT 6RDS 6SS 6ST 6STR 6WD 6WH 6WV 6X6 6ZYL 7SS 7STR 8CL 8CLT 8CM 8CTF 8WD 8X8 8ZYL 9STR A&E A&F A&J A1GP A4K A4WD A5K A7C AAA AAAA AAAFTS AAAM AAAS AAB AABC AABS AAC AACA AACC AACET AACF AACN AAD AADA AADF AADT AADTT AAE AAF AAFEA AAFLS AAFRSR AAG AAGT AAHF AAI AAIA AAITF AAIW AAK AAL AALA AALM AAM AAMA AAMVA AAN AAOL AAP AAPAC AAPC AAPEC AAPEX AAPS AAPTS AAR AARA AARDA AARN AARS AAS AASA AASHTO AASP AASRV AAT AATA AATC AAV AAV8 AAW AAWDC AAWF AAWT AAZ ABA ABAG ABAN ABARS ABB ABC ABCA ABCV ABD ABDC ABE ABEIVA ABFD ABG ABH ABHP ABI ABIAUTO ABK ABL ABLS ABM ABN ABO ABOT ABP ABPV ABR ABRAVE ABRN ABRS ABS ABSA ABSBSC ABSL ABSS ABSSL ABSV ABT ABTT -

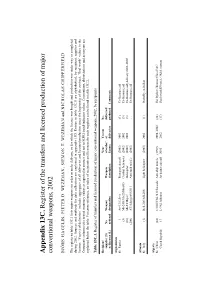

Appendix 13C. Register of the Transfers and Licensed Production of Major Conventional Weapons, 2002

Appendix 13C. Register of the transfers and licensed production of major conventional weapons, 2002 BJÖRN HAGELIN, PIETER D. WEZEMAN, SIEMON T. WEZEMAN and NICHOLAS CHIPPERFIELD The register in table 13C.1 lists major weapons on order or under delivery, or for which the licence was bought and production was under way or completed during 2002. Sources and methods for data collection are explained in appendix 13D. Entries in table 13C.1 are alphabetical, by recipient, supplier and licenser. ‘Year(s) of deliveries’ includes aggregates of all deliveries and licensed production since the beginning of the contract. ‘Deal worth’ values in the Comments column refer to real monetary values as reported in sources and not to SIPRI trend-indicator values. Conventions, abbreviations and acronyms are explained below the table. For cross-reference, an index of recipients and licensees for each supplier can be found in table 13C.2. Table 13C.1. Register of transfers and licensed production of major conventional weapons, 2002, by recipients Recipient/ Year Year(s) No. supplier (S) No. Weapon Weapon of order/ of delivered/ or licenser (L) ordered designation description licence deliveries produced Comments Afghanistan S: Russia 1 An-12/Cub-A Transport aircraft (2002) 2002 (1) Ex-Russian; aid (5) Mi-24D/Mi-25/Hind-D Combat helicopter (2002) 2002 (5) Ex-Russian; aid (10) Mi-8T/Hip-C Helicopter (2002) 2002 (3) Ex-Russian; aid; delivery 2002–2003 (200) AT-4 Spigot/9M111 Anti-tank missile (2002) . Ex-Russian; aid Albania S: Italy (1) Bell-206/AB-206 Light helicopter