Humber River State of the Watershed Report – Land and Resource Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Past to the Future of Landfill Engineering Through Case Histories

Missouri University of Science and Technology Scholars' Mine International Conference on Case Histories in (1998) - Fourth International Conference on Geotechnical Engineering Case Histories in Geotechnical Engineering 08 Mar 1998 - 15 Mar 1998 From the Past to the Future of Landfill Engineering Through Case Histories R. Kerry Rowe University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/icchge Part of the Geotechnical Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Rowe, R. Kerry, "From the Past to the Future of Landfill Engineering Through Case Histories" (1998). International Conference on Case Histories in Geotechnical Engineering. 4. https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/icchge/4icchge/4icchge-session00/4 This Article - Conference proceedings is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars' Mine. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Conference on Case Histories in Geotechnical Engineering by an authorized administrator of Scholars' Mine. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 145 Proceedings: Fourth International Conference on Case Histories in Geotechnical Engineering~ St. Louis, Missouri, March 9-12, 1998. FROM THE PAST TO THE FUTURE OF LANDFILL ENGINEERING THROUGH CASE HISTORIES R. Kerry Rowe Paper No. SOA-9 Dept. of Civil & Environmental Engineering University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada N6A 5B9 AIISTRACT The advances in landfill engineering are outlined based on a number of case histories illustrating past problems, hydraulic performance of clay liners, diffusive transport through liners, hydraulic containment and clogging of leachate collection systems. -

As Toronto Finds Distant Holes for Its Waste, the 905 Sees Incineration in a New, Appealing Light July 30, 2007

Toronto Star As Toronto finds distant holes for its waste, the 905 sees incineration in a new, appealing light July 30, 2007 Phinjo Gombu STAFF REPORTER Despite skepticism and some opposition, Durham Region is deeply committed to building the GTA's first garbage incinerator in 15 years, says the region's works commissioner. "Years ago, there was a fundamental commitment by Durham Region that there would be no new landfills established (here)," says Cliff Curtis. "And council seems to have bought into the concept that we need to look after our own waste." That seems to be a unique position in the GTA, where disposing of trash in one's own backyard tends to stink politically. Sustainable self-sufficiency, with acceptance of some risk, is a goal other regions seem to be avoiding. Toronto and Peel have signed long-term deals to use landfills outside the GTA, though Peel already incinerates half its waste. York plans to turn some of its garbage into pellets to be burned somewhere else. For the time being, Halton has decided to continue to use a Milton landfill. After the province promised Michigan legislators that Ontario would stop shipping garbage to landfills in the state by 2010, councils across the GTA scrambled to find alternatives. Most have taken a step back from incineration, long fraught with concerns about emissions. Halton Region decided to defer considering an energy-from-waste incinerator for five years. Peel signed a long-term deal with a landfill near Sarnia for half of its trash, despite the fact its Algonquin Power plant in Brampton, built in 1992, already burns almost 140,000 tonnes of garbage a year and is undergoing a retrofit so it can dispose of more. -

Trailside Esterbrooke Kingslake Harringay

MILLIKEN COMMUNITY TRAIL CONTINUES TRAIL CONTINUES CENTRE INTO VAUGHAN INTO MARKHAM Roxanne Enchanted Hills Codlin Anthia Scoville P Codlin Minglehaze THACKERAY PARK Cabana English Song Meadoway Glencoyne Frank Rivers Captains Way Goldhawk Wilderness MILLIKEN PARK - CEDARBRAE Murray Ross Festival Tanjoe Ashcott Cascaden Cathy Jean Flax Gardenway Gossamer Grove Kelvin Covewood Flatwoods Holmbush Redlea Duxbury Nipigon Holmbush Provence Nipigon Forest New GOLF & COUNTRY Anthia Huntsmill New Forest Shockley Carnival Greenwin Village Ivyway Inniscross Raynes Enchanted Hills CONCESSION Goodmark Alabast Beulah Alness Inniscross Hullmar Townsend Goldenwood Saddletree Franca Rockland Janus Hollyberry Manilow Port Royal Green Bush Aspenwood Chapel Park Founders Magnetic Sandyhook Irondale Klondike Roxanne Harrington Edgar Woods Fisherville Abitibi Goldwood Mintwood Hollyberry Canongate CLUB Cabernet Turbine 400 Crispin MILLIKENMILLIKEN Breanna Eagleview Pennmarric BLACK CREEK Carpenter Grove River BLACK CREEK West North Albany Tarbert Select Lillian Signal Hill Hill Signal Highbridge Arran Markbrook Barmac Wheelwright Cherrystone Birchway Yellow Strawberry Hills Strawberry Select Steinway Rossdean Bestview Freshmeadow Belinda Eagledance BordeauxBrunello Primula Garyray G. ROSS Fontainbleau Cherrystone Ockwell Manor Chianti Cabernet Laureleaf Shenstone Torresdale Athabaska Limestone Regis Robinter Lambeth Wintermute WOODLANDS PIONEER Russfax Creekside Michigan . Husband EAST Reesor Plowshare Ian MacDonald Nevada Grenbeck ROWNTREE MILLS PARK Blacksmith -

Fieldguide Issue 09

FieldGuide issue 09 expert advice • informative interviews • great recipes exciting communities • and more... - 2016 - SEARCHING FOR YOUR NEW HOME? CONSIDER OUR ESTABLISHED GTA COMMUNITIES! “Your perfect GTA hen looking for the home that is right for you and your family, there are lifestyle starts with a lot of factors to consider. Location is of course paramount. In the GTA this means finding a neighbourhood that gives you the access to natural Fieldgate Homes. and urban amenities that you desire, as well as being within a convenient Wdistance to your place of work. Beyond location though, you really need to find a home buying opportunity that inspires confidence; one that features a home product that ” has a proven track record for both quality of construction and functionality of design. This is one of the best approaches to ensure that you are purchasing a home and a neighbourhood that you and your family will enjoy over time. A great way to choose the right home and community for your family is to simply see the existing homes in the community for yourself. That’s why our current home communities offer such an exciting opportunity for GTA homebuyers. Valleylands in Brampton, Impressions in Kleinburg and Blue Sky in Stouffville are already home to many hundreds of satisfied residents. When visiting our Presentation Centres, we often encourage homebuyers to take a quick drive through these earlier phases of the communities to see the remarkably consistent high levels of quality and style that they can enjoy when they purchase in a Fieldgate Homes community. Learn more about the current releases at these highly popular established communities below. -

Humber River Watershed Plan Pathways to a Healthy Humber June 2008

HUMBER RIVER WATERSHED PLAN PAThwAYS TO A HEALTHY HUMBER JUNE 2008 Prepared by: Toronto and Region Conservation © Toronto and Region Conservation 2008 ISBN: 978-0-9811107-1-4 www.trca.on.ca 5 Shoreham Drive, Toronto, Ontario M3N 1S4 phone: 416-661-6600 fax: 416-661-6898 HUMBER RIVER WATERSHED PLAN PATHWAYS TO A HEALTHY HUMBER JUNE 2008 Prepared by: Toronto and Region Conservation i Humber River Watershed Plan, 2008 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This Humber River Watershed Plan—Pathways to a Healthy Humber—was written by Suzanne Barrett, edited by Dean Young and represents the combined effort of many participants. Appreciation and thanks are extended to Toronto and Region Conservation staff and consultants (listed in Appendix F) for their technical support and input, to government partners for their financial support and input, and to Humber Watershed Alliance members for their advice and input. INCORPORATED 1850 Humber River Watershed Plan, 2008 ii HUMBER RIVER WATERSHED PLAN PATHWAYS TO A HEALTHY HUMBER EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Humber River watershed is an extraordinary resource. It spans 903 square kilometres, from the headwaters on the Niagara Escarpment and Oak Ridges Moraine down through fertile clay plains to the marshes and river mouth on Lake Ontario. The watershed provides many benefits to the people who live in it. It is a source of drinking water drawn from wells or from Lake Ontario. Unpaved land absorbs water from rain and snowfall to replenish groundwater and streams and reduce the negative impacts of flooding and erosion. Healthy aquatic and terrestrial habitats support diverse communities of plants and animals. Agricultural lands provide local sources of food and green spaces provide recreation opportunities. -

Attachment 1: Table of Projects Being Planned Under the ERMP in 2021

Attachment 1: Table of projects being planned under the ERMP in 2021 Municipality Ward Project Name Portfolio 2021 Project Status City of Brampton 2 Wegneast Valley Erosion Control Project Region of Peel Erosion Control & Infrastructure Protection Construction City of Brampton 7 I-360/I-361 Region of Peel Erosion Control & Infrastructure Protection Study, Planning or Design York Region Streambank Infrastructure Erosion Control City of Markham 1 German Mills Settlers Park Sites 2-3 Sanitary Infrastructure Protection Management Program Study, Planning or Design City of Markham 4 70 Main Street South Erosion Control Project TRCA Maintenance & Other Hazards (York Region) Construction City of Mississauga 5 Brandon Gate Park - Bank Stabilization Project Region of Peel Erosion Control & Infrastructure Protection Construction City of Mississauga 5 I-700 Region of Peel Erosion Control & Infrastructure Protection Study, Planning or Design York Region Streambank Infrastructure Erosion Control City of Richmond Hill 5 Patterson Creek I-066, I-067, I-065, I-064, P-102 Management Program Post-Construction York Region Streambank Infrastructure Erosion Control City of Richmond Hill 5 Patterson Creek near North Richvale Sanitary Infrastructure Protection Management Program Construction City of Richmond Hill 5 Patterson Valley South Richvale Erosion Hazards Fee For Service Post-Construction City of Toronto 1 22-24 Bucksburn Road Erosion Control and Slope Stabilization Project Valley Erosion Hazards Study, Planning or Design City of Toronto 1 Hadrian Drive -

A Review of Landfill Leachate Treatment by Microalgae: Current

processes Review A Review of Landfill Leachate Treatment by Microalgae: Current Status and Future Directions Tabish Nawaz 1,2, Ashiqur Rahman 3,4 , Shanglei Pan 1,5, Kyleigh Dixon 5, Burgandy Petri 5 and Thinesh Selvaratnam 1,3,5,* 1 Center for Advances in Water & Air Quality, Lamar University, 4400 S M L King Jr Pkwy, Beaumont, TX 77705, USA; [email protected] (T.N.); [email protected] (S.P.) 2 Environmental Science and Engineering Department, Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, Powai, Mumbai, Maharashtra 400076, India 3 Center for Midstream Management and Science, Lamar University, 4400 S M L King Jr Pkwy, Beaumont, TX 77705, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Chemical Engineering, Lamar University, 4400 S M L King Jr Pkwy, Beaumont, TX 77705, USA 5 Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering, Lamar University, 4400 S M L King Jr Pkwy, Beaumont, TX 77705, USA; [email protected] (K.D.); [email protected] (B.P.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-409-880-8712 Received: 28 February 2020; Accepted: 19 March 2020; Published: 26 March 2020 Abstract: Solid waste generation has been projected to increase worldwide. Presently, the most applied methodology to dispose of solid waste is landfilling. However, these landfill sites, over time release a significant quantity of leachate, which can pose serious environmental issues, including contamination of water resources. There exist many physicochemical and biological landfill leachate treatment schemes with varying degrees of success. With an increasing focus on sustainability, there has been a demand for developing eco-friendly, green treatment schemes for landfill leachates with viable resource recovery and minimum environmental footprints. -

Compliance Boundary at the Keele Valley Landfill Site

Compliance Boundary at the Keele Valley Landfill Site (City Council on August 1, 2, 3 and 4, 2000, adopted this Clause, without amendment.) The Policy and Finance Committee and the Works Committee jointly recommend the adoption of the following report (June 27, 2000) from the Commissioner of Works and Emergency Services: Purpose: To obtain the approval of City Council to request the Ministry of the Environment (MOE) to move the compliance boundary of the Keele Valley Landfill Site from the edge of the secondary buffer lands south of the City-owned lands northwards to the south end of a modified primary buffer, to take place upon the completion of landfilling operations at Keele Valley. Financial Implications and Impact Statement: If the recommendation is approved, subject to the conditions suggested, there are no financial implications to the City of Toronto. Recommendations: It is recommended that: (1) the City of Toronto request the Ministry of the Environment to amend the Certificate of Approval applicable to the Keele Valley Landfill Site to move the compliance boundary of the landfill from the south end of the secondary buffer lands at Major Mackenzie Drive to the south of the primary buffer lands as redefined as set out in this report; (2) Recommendation No. (1) be subject to the following conditions: (a) York Major Holdings, the owner of the lands comprising the secondary buffer, enter into an agreement with the City of Toronto incorporating the following provisions: (i) any new land use on the lands that are currently part of -

Solid Waste Management Services Staff Recommended 2020 Operating Budget 2020 – 2029 Capital Budget & Plan

Solid Waste Management Services Staff Recommended 2020 Operating Budget 2020 – 2029 Capital Budget & Plan Budget Briefing to Budget Committee November 15, 2019 While we aim to provide fully accessible content, there is no text alternative available for some of the content within these pages. If you require alternate formats or need assistance understanding our charts, graphs, or any other content, please contact us at 416-392-7896 or [email protected]. Overview Overview and Highlights 2020 Staff Recommended Operating Budget and Plan 2020 – 2029 Staff Recommended Capital Budget and Plan Rate Changes 2 Overview and Highlights 3 Solid Waste Management Services – What We Do Solid Waste Management Services (SWMS) is an Integrated System and is responsible for: Integrated Waste Management System City Beautification Collection & Processing & Education & Residual Transfer Transport Enforcement Management SWMS manages 7 Transfer Stations, 2 Organics Processing Facility with one under expansion, 3 Collection Yards and 1 Litter Collection Yard, Green Lane Landfill + 160 Closed Landfills, 1.5 million residential bins and operates approximately 750 vehicles and pieces of equipment with an asset value of $700M . 4 Solid Waste Management Services – What is Seen After Raptors Parade / After SWM Parks and Curbside Collection 5 Solid Waste Management Services – How It’s Done Litter Management Collections Transfer Stations Haulage Open and Closed Landfill Mgmt. Recycling Processing Recycling Marketing Organics Processing in Renewable Natural Gas Special Waste Handling Anaerobic Digesters Development Community Outreach Policy & Research Customer Experience Circular Economy Asset Mgmt. & Capital Delivery Facility Maintenance Technology / Smart City Innovation Education Business Services 6 Solid Waste Management Services - Highlights • Completed an organizational realignment • New Safety Strategy and Program Initiated • Negotiated contracts for D2 collections, Disco Org. -

Meeting #2/13

INDEX TO EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE MEETING #2/13 Friday, April 12, 2013 MINUTES Minutes of Meeting #1/13, held on March 1, 2013 47 DELEGATION Bilimoria, Dinesh, Mr. of 146 Robirwin Street, Whitchurch-Stouffville re: Request for Disposal of Toronto and Region Conservation Authority - owned land47 CORRESPONDENCE A letter from John Taranu, Cycle Toronto, in regard to 2015 Pan Am Games Legacy Project. 48 GREENLANDS ACQUISITION PROJECT FOR 2011-2015 Flood Plain and Conservation Component, Humber River Watershed Lea Vivot and 11220 Highway 27 Holdings Inc. 52 REQUEST FOR DISPOSAL OF TORONTO AND REGION CONSERVATION AUTHORITY-OWNED LAND Rear of 146 Robirwin Street, Town of Whitchurch-Stouffville 59 ROGERS COMMUNICATIONS INC. Proposal for Lease of Land 59 ROGERS COMMUNICATIONS INC. Proposal for Lease of Land, Vicinity of Lake St. George Field Centre 63 TOWN OF AJAX Request for a Permanent Easement for the Pedestrian Bridge, Town of Ajax, Regional Municipality of Durham, Carruthers Creek 67 EMPIRE COMMUNITIES (2183 LAKESHORE BLVD.) LTD. Lease of Land, Marine Parade Drive, West of Lakeshore Boulevard West, City of Toronto 70 OFFICE ACCOMMODATION Renewal of Office Space Lease at the Earth Rangers Centre 73 SCARBOROUGH WATERFRONT ACCESS PLAN City of Toronto 75 ASHBRIDGE’S BAY CLASS ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT Coastal Engineering Services 83 BURNHAMTHORPE SUSTAINABLE NEIGHBOURHOOD RETROFIT ACTION PLAN Consultant Selection 87 REGIONAL WATERSHED MONITORING PROGRAM Contract for 2013 Surface Water Quality Laboratory Analysis 89 LOTUS NOTES SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT Award of Sole Source Contract for Consulting Services 92 ACQUISITION OF A MEDIUM DUTY TRUCK Contract FM2013-02 94 SUPPLY OF RENTAL RATES FOR AN OPERATED HYDRAULIC BACKHOE Award of Contract RSD13-036 96 WWK RECREATION INC. -

History of Toronto from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia the History of Toronto, Ontario, Canada Begins Several Millennia Ago

History of Toronto From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The history of Toronto, Ontario, Canada begins several millennia ago. Archaeological finds in the area have found artifacts of First Nations settlements dating back several thousand years. The Wyandot people were likely the first group to live in the area, followed by the Iroquois. When Europeans first came to Toronto, they found a small village known as Teiaiagon on the banks of the Humber River. Between visits by European explorers, the village was abandoned by the Iroquois, who moved south of Lake Ontario and the Mississaugas, a branch of the Ojibwa settled along the north shore of the lake. The French first set up trading posts in the area, including Fort Rouillé in 1750, which they abandoned as the British conquered French North America. In 1788, the British negotiated the first treaty to take possession of the Toronto area from the Mississaugas. After the United States War of Independence, the area north of Lake Ontario was held by the British who set up the province of Upper Canada in 1791. See also: Name of Toronto https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:DavenportBathurstSoutheast.jpg Davenport Road, as shown here in 1914, does not follow Toronto's standard street grid pattern, as it originated as a First Nations travel route between the Humber River and the Don Valley named Gete-Onigaming, Ojibwe for "at the old portage."[1] Toronto is located on the northern shore of Lake Ontario, and was originally a term of indeterminate geographical location, designating the approximate area of the future city of Toronto on maps dating to the late 17th and early 18th century. -

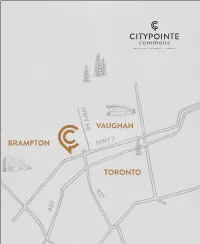

Brampton Toronto Vaughan

HWY 50 VAUGHAN BRAMPTON HWY 7 TORONTO 427 407 LIVE WHERE BRAMPTON VAUGHAN & TORONTO CONNECT COMMON POINTS CONNECT US ALL LIVE WHERE BRAMPTON VAUGHAN & TORONTO CONNECT Life in the GTA is all about connection. After all, this is Canada’s most dynamic urban landscape. A place where so many cities find common points of connection. Each city offers its own unique flavour, and when they come together, you get an exceptional lifestyle that is greater than the sum of its parts. 01 LIVE WHERE BRAMPTON VAUGHAN & TORONTO CONNECT POINT TO ENDLESS POSSIBILITIES CityPointe Commons is a new community that enhances the existing connectivity between 3 of the GTA’s greatest cities. Located at The Gore Rd. & Queen St. E., CityPointe connects you to the best that Brampton, Vaughan and Toronto have to offer. In addition to having 3 amazing cities in which you can choose to spend your time, CityPointe Commons also lets you choose your home from 3 acclaimed GTA builders. Amazing cities, a vibrant BRAMPTON community and an incredible home selection all point to one thing: this might just be the GTA’s most exciting new place to call home. VAUGHAN TORONTO 03 LIVE WHERE BRAMPTON VAUGHAN & TORONTO CONNECT CENTRAL. CONVENIENT. CONNECTED. At CityPointe, all the best of the GTA is never far from home. Take a look around, and you’ll be amazed to find countless popular destinations are all just minutes away. EASY ACCESS TO THE GTA’S TOP POINTS OF INTEREST 3 MINUTES TO CLAIRVILLE 10 MINUTES TO CONSERVATION AREA PEARSON AIRPORT 12 MINUTES 12 MINUTES TO TO KLEINBURG VAUGHAN CITY CENTRE 20 MINUTES TO 30 MINUTES TO LAKE ONTARIO DOWNTOWN TORONTO 05 LIVE WHERE BRAMPTON VAUGHAN & TORONTO CONNECT 700+ SHOPS & RESTAURANTS NEARBY Much of the best high-end shopping can be found just minutes from your door.