— Materials for a History of the Persian Narrative Tradition Two

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Turan-Dokht-Programme.Pdf

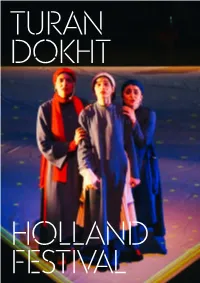

TURAN DOKHT HOLLAND FESTIVAL TURAN DOKHT Aftab Darvishi Miranda Lakerveld Nilper Orchestra thanks to production partner patron coproduction CONTENT Info & context Credits Synopsis Notes A conversation with Miranda Lakerveld About the artists Friends Holland Festival 2019 Join us Colophon INFO CONTEXT date & starting time introduction Wed 5 June 2019, 8.30 pm by Peyman Jafari Thu 6 June 2019, 8.30 pm 7.45 pm venue Hamid Dabashi – Persian culture on Muziekgebouw The Global Scene Thu 6 Juni, 4 pm running time Podium Mozaïek 1 hour 20 minutes no interval language Farsi and Italian with English and Dutch surtitles CREDITS composition production Aftab Darvishi World Opera Lab, Jasper Berben libretto, direction with support of Miranda Lakerveld Fonds Podiumkunsten, Gieskes-Strijbis Fonds, Amsterdams Fonds voor de Kunst, conductor Nederlandse Ambassade Tehran Navid Gohari world premiere video 24 February 2019 Siavash Naghshbandi Azadi Tower, Tehran light Turan Dokht is inspired by the Haft Bart van den Heuvel Peykar of Nizami Ganjavi and Turandot by Giacomo Puccini. The fragments of costumes Puccini’s Turandot are used with kind per- Nasrin Khorrami mission of Ricordi Publishing House. dramaturgy, text advice All the flights that are made for this Asghar Seyed-Gohrab project are compensated for their CO2 emissions. vocals Ekaterina Levental (Turan Dokht), websites Arash Roozbehi (The unknown prince), World Opera Lab Sarah Akbari, Niloofar Nedaei, Miranda Lakerveld Tahere Hezave Aftab Darvishi acting musicians Yasaman Koozehgar, Yalda Ehsani, Mahsa Rahmati, Anahita Vahediardekani music performed by Behzad Hasanzadeh, voice/kamanche Mehrdad Alizadeh Veshki, percussion Nilper Orchestra SYNOPSIS The seven beauties from Nizami’s Haft Peykar represent the seven continents, the seven planets and the seven colours. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Narrative and Iranian

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Narrative and Iranian Identity in the New Persian Renaissance and the Later Perso-Islamicate World DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History by Conrad Justin Harter Dissertation Committee: Professor Touraj Daryaee, Chair Professor Mark Andrew LeVine Professor Emeritus James Buchanan Given 2016 © 2016 Conrad Justin Harter DEDICATION To my friends and family, and most importantly, my wife Pamela ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS v CURRICULUM VITAE vi ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION vii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 2: Persian Histories in the 9th-12th Centuries CE 47 CHAPTER 3: Universal History, Geography, and Literature 100 CHAPTER 4: Ideological Aims and Regime Legitimation 145 CHAPTER 5: Use of Shahnama Throughout Time and Space 192 BIBLIOGRAPHY 240 iii LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure 1 Map of Central Asia 5 iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to all of the people who have made this possible, to those who have provided guidance both academic and personal, and to all those who have mentored me thus far in so many different ways. I would like to thank my advisor and dissertation chair, Professor Touraj Daryaee, for providing me with not only a place to study the Shahnama and Persianate culture and history at UC Irvine, but also with invaluable guidance while I was there. I would like to thank my other committee members, Professor Mark LeVine and Professor Emeritus James Given, for willing to sit on my committee and to read an entire dissertation focused on the history and literature of medieval Iran and Central Asia, even though their own interests and decades of academic research lay elsewhere. -

The Nizami of Azerbaijan and the World

Great people THE NIZAMI OF AZERBAIJAN AND THE WORLD Rafael HUSEYNOV Doctor of Philology, Professor, Corresponding Member of the ANAS ON SATURDAY, 30 SEPTEMBER 1139, A VERY SERIOUS EVENT HAPPENED IN THE HISTORY OF THE EARTH. IT WAS ONE OF THE MOST DEVASTAT ING EARTHQUAKES IN WORLD HIS TORY AND TURNED THE EARTH UP SIDE DOWN. MEDIEVAL HISTORIANS RECORDED THAT THIS EARTHQUAKE, WHICH HAPPENED IN THE CITY OF GANJA, HAD NO ANALOGUES FOR THE DEVASTATION IT CAUSED. he earthquake totally destroyed Ganja. But in its stead, it created Ta natural wonder like Goygol. The earthquake killed tens of thou- sands of people. But to compen- sate for all those losses, nature gave Azerbaijan and the world an unusual child in 1141. A genius poet and phi- losopher, who became known as Nizami Ganjavi later, whose pieces woke people’s spirit and thoughts for centuries and whose works became a school, was born. Nizami Ganjavi has long ceased to be only Azerbaijan’s child. His lit- “Nizami in his native Ganja” by Eyyub Mammadov 38 www.irs-az.com erary heritage is part of the treasury born in the city of Qom in Iran. is still originally from Ganja of humanity’s most valuable assets, while he himself rose to such a level Cho dorr garcheh dar bahr-e Ganjeh Some sources (for example, that he became a child of all peoples qomam Daulatshah Samarqandi, 15th centu- and humanity. In his lifetime, Niza- Vali az gahestane shahre Qomam ry) say that Nizami had a poet broth- mi Ganjavi believed that his works er named Givami Mutarrizi. -

Contributionstoa292fiel.Pdf

Field Museum OF > Natural History o. rvrr^ CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE ANTHROPOLOGY OF IRAN BY HENRY FIELD CURATOR OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY ANTHROPOLOGICAL SERIES FIELD MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY VOLUME 29, NUMBER 2 DECEMBER 15, 1939 PUBLICATION 459 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS PLATES 1. Basic Mediterranean types. 2. Atlanto- Mediterranean types. 3. 4. Convex-nosed dolichocephals. 5. Brachycephals. 6. Mixed-eyed Mediterranean types. 7. Mixed-eyed types. 8. Alpinoid types. 9. Hamitic and Armenoid types. 10. North European and Jewish types. 11. Mongoloid types. 12. Negroid types. 13. Polo field, Maidan, Isfahan. 14. Isfahan. Fig. 1. Alliance Israelite. Fig. 2. Mirza Muhammad Ali Khan. 15-39. Jews of Isfahan. 40. Isfahan to Shiraz. Fig. 1. Main road to Shiraz. Fig. 2. Shiljaston. 41. Isfahan to Shiraz. Fig. 1. Building decorated with ibex horns at Mahyar. Fig. 2. Mosque at Shahreza. 42. Yezd-i-Khast village. Fig. 1. Old town with modern caravanserai. Fig. 2. Northern battlements. 43. Yezd-i-Khast village. Fig. 1. Eastern end forming a "prow." Fig. 2. Modern village from southern escarpment. 44. Imamzadeh of Sayyid Ali, Yezd-i-Khast. 45. Yezd-i-Khast. Fig. 1. Entrance to Imamzadeh of Sayyid Ali. Fig. 2. Main gate and drawbridge of old town. 46. Safavid caravanserai at Yezd-i-Khast. Fig. 1. Inscription on left wall. Fig. 2. Inscription on right wall. 47. Inscribed portal of Safavid caravanserai, Yezd-i-Khast. 48. Safavid caravanserai, Yezd-i-Khast. Fig. 1. General view. Fig. 2. South- west corner of interior. 49-65. Yezd-i-Khast villagers. 66. Kinareh village near Persepolis. 67. Kinareh village. -

Rustaveli and Nizami

Shota Rustaveli Institute of Georgian Literature Intercultural Space: Rustaveli and Nizami Tbilisi 2021 1 UDK )ირააირ 29.( .8.281. .1.8 )ილევათსურ 29.( .1.821.128 919-ი TSU Shota Rustaveli Institute of Georgian Literature This Book was prepared as part of the Basic Research Grant Project (N FR17_109), supported by the Shota Rustaveli National Science Foundation of Georgia. Editors: Maka Elbakidze, Ivane Amirhanashvili ©Ivane Amirkhanashvili, Maka Elbakidze, Nana Gonjilashvili, Lia Karichashvili, Irma Ratiani, Oktai Kazumov, Lia Tsereteli, Firuza Abdulaeva, Zahra Allahverdiyeva, Nushaba Arasli, Samira Aliyeva, Tahmina Badalova, Hurnisa Bashirova, Isa Habibbayli, Abolfasl Muradi Rasta. Layout: Tinatin Dugladze Cover by ISBN 2 Contents Preface.....………………………………………………………………….…7 Rustaveli and Nizami – Studies in Historical Context Lia Tsereteli On the History of Studying the Topic…………………………222……211 Zahra Allahverdieva On history of study of Nizami Ganjavi and Shota Rustaveli in Azerbaijan…………………………………..…31 Rustaveli - The Path to Renaissance Maka Elbakidze The Knight in the Panther's Skin – the path of Georgian literature to Renaissance………………………2239 Nizami – Poet and Thinker Isa Habibbayli Great Azerbaijani Poet Nizami Ganjavi……………………………22…57 Zahra Allahverdiyeva Philosophy of Love of Nizami Ganjavi…………………………...……78 3 Zahra Allahverdiyeva Nizami Ganjavi's “Iskandar-nameh”…………………………22………292 Hurnisa Bashirova The epic poem ”Leyli and Majnun”………………………………..…112 of Nizami Ganjavi Nushaba Arasli The Fourth Poem of the „Five Treasures“…………………………....120 Samira Aliyeva The Lyrics of Nizami Ganjavi…………………………………………8.. Tahmina Badalova Nizami Ganjavi and World Literature………………………………..168 Nushaba Arasli Nizami and Turkish Literature…………………………………….…2190 Aesthetic Views of Rustaveli and Nizami Ivane Amirkhanashvili Nizami and Rustaveli: Time and the Aesthetic Creed……………………………………..…2203 Irma Ratiani The Three Realities in Rustaveli……………………………………22.221 Ivane Amirkhanashvili The Cosmological Views of Rustaveli and Nizami…………………22.. -

An Analytical Study on Ministerial Organizations Status in the Historiography of Ravandi Reza Bitarafan University of Isfahan, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln June 2018 An analytical study on ministerial organizations status in the historiography of Ravandi Reza Bitarafan University of Isfahan, [email protected] Fereydoon Allahyari Department of History, University of Isfahan, Iran Ali Akbar Kajbaf Department of History, University of Isfahan, Iran Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Asian History Commons, and the Library and Information Science Commons Bitarafan, Reza; Allahyari, Fereydoon; and Kajbaf, Ali Akbar, "An analytical study on ministerial organizations status in the historiography of Ravandi" (2018). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 1848. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1848 An analytical study on ministerial organizations status in the historiography of Ravandi, Iran Reza Bitarafan, Ph.D. Std. Department of History, University of Isfahan, Iran [email protected] Fereydoon Allahyari, Ph.D. (Corresponding Author) Professor, Department of History, University of Isfahan, Iran [email protected] Ali Akbar Kajbaf, Ph.D. [email protected] Professor, Department of History, University of Isfahan, Iran Abstract The ministry organization as a symbol of Iranian sreaming is the important element in Iranian historiography. Reproduction of many of Iranshahri thoughts teachings in Seljuk's period provided background for note historians to ministry organization. With the domination of Turks on Iran was established ministry s status until free rulers of the art of government benefit of ministry's knowledge. Ravandi was one of the important historians in Seljuk's period. -

Scientific Expressions in Abolfaraj Rouni's Anthology

Open Journal of Modern Linguistics, 2016, 6, 373-389 http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojml ISSN Online: 2164-2834 ISSN Print: 2164-2818 Scientific Expressions in Abolfaraj Rouni’s Anthology Mohammad Reza Najjarian* Department of Persian Language and Literature, Yazd University, Yazd, Iran How to cite this paper: Najjarian, M. R. Abstract (2016). Scientific Expressions in Abolfaraj th Rouni’s Anthology. Open Journal of Mod- Abolfaraj Rouni is a pioneer of a new poetry style who has influenced all the 6 cen- ern Linguistics, 6, 373-389. tury (A.H) poets directly and indirectly. His own and his followers’ poems have http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojml.2016.65034 served as a basis for changing the Khorasani style to Iraqi style. His anthology is Received: November 3, 2015 fraught with a variety of Arabic words and Expressions, Quranic tenets, literary fig- Accepted: May 20, 2016 ures, and poetic features. One can specifically refer to his exotic overstatements Published: October 14, 2016 about the eulogized. To understand his poems is generally difficult because it calls for a perfect knowledge of such field as astronomy, rhetoric, logic, philosophy, theology, Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. and the like. Here is a typical verse of such poems: Thou at rest like the poles, But in This work is licensed under the Creative race like the moon. Abolfaraj has based his imagery upon science. He has also uti- Commons Attribution International lized conventions such as games of chess as well as literary issues as associations for License (CC BY 4.0). -

Analyses of the Reflection of Painting in the Opuses of Nezami Ganjavi (12Th Century AD)

Vol.14/No.51/Sep 2017 Received 2016/11/27 Accepted 2017/06/06 Persian translation of this paper entitled: تحلیل بازتاب نقاشی در جامعه قرن ششم هجری با نگرش به آثار نظامی گنجوی also published in this issue of journal. Analyses of the Reflection of Painting in the Opuses of Nezami Ganjavi (12th century AD) Maryam Khorrami* Minoo Khany** Abstract Poem is a beautiful narration of history, and the poet takes it from people and their life essence. In Persian literature, “Nezami” is one of the strongest pillars in storytelling and lyrics. His poems are nothing but the social reality of his era. This research is trying to find the answer to this question that how the art of painting in society of 12th century ad is reflected in the poems of Nezami? The theoretical framework used in this research is the reflection theory in sociology of art. This theory is based on assumption of art as the mirror of society and reflector of its characters. The research methodology used in this research is library and the technic which is used is content analyses. The aim of this research is reaching to new information in the field of painting in aforementioned century. It is hypothesized that “the concepts of Nezami’s poems was taken from the social attitude of his era and was affected by life issues, and this could indirectly give useful information about various things to the researcher, including art of painting in society of 12th century ad”. The method of this research is content analysis and the data collection method was through library and included studying Nezami’s works in 12th century. -

Rashīd Al-Dīn and the Making of History in Mongol Iran

Rashīd al-Dīn and the making of history in Mongol Iran Stefan T. Kamola A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: Joel Walker, Chair Charles Melville (Cambridge) Purnima Dhavan Program Authorized to Offer Degree: History ©Copyright 2013 Stefan Kamola University of Washington Abstract Rashīd al-Dīn and the making of history in Mongol Iran Stefan T. Kamola Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor Joel Walker History The Jāmiʿ al-tawārīkh (Collected histories) of Rashīd al-Dīn Ṭabīb (d. 1318) has long been considered the single richest witness to the history of the early Mongol Empire in general and its Middle Eastern branch, the Ilkhanate, in particular. This has created a persistent dependence on the work as a source of historical data, with a corresponding lack of appreciation for the place it holds within Perso-Islamic intellectual history. This understanding of Rashīd al-Dīn and the Jāmiʿ al-tawārīkh, however, does not match certain historiographical and ideological strategies evident in the work itself and in other works by Rashīd al-Dīn and his contemporaries. This dissertation reads beyond the monolithic and uncritical use of the Jāmiʿ al-tawārīkh that dominates modern scholarship on Mongol and Ilkhanid history. Instead, it fits Rashīd al-Dīn and his work into the difficult process of transforming the Mongol Ilkhans from a dynasty of foreign military occupation into one of legitimate sovereigns for the Perso-Islamic world. This is the first study to examine a full range of Persianate cultural responses to the experience of Mongol conquest and rule through the life and work of the most prominent statesman of the period. -

Mahmoud Zabah Ahmed Hussein Pour Sar Karizi

QUID 2017, pp. 2720-2731, Special Issue N°1- ISSN: 1692-343X, Medellín-Colombia A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF LAYLA AND MAJNUN BELONGS TO NIZAMI'S WORK AND LAYLA AND MAJNUN BELONGS TO GHASEMI GONABADI ' WORK (Recibido 05-06-2017. Aprobado el 07-09-2017) Ahmed Hussein Pour Sar Karizi Mahmoud Zabah Department ofPersian Language and Department ofPersian Language and Literature,Torbat-e Heydarieh Branch,Islamic Literature,Torbat-e Heydarieh Branch,Islamic Azad University, Torbat-e Heydarieh,Iran Azad University, Torbat-e Heydarieh,Iran Abstract.One of the most extensive areas of Persian 's poem is the range of lyric poems and in this meanwhile, the most considerable part of such area is allocated to the romantic masnavi of Persian’s poem . The aim of this study was conducted to compare the two romantic stories of Persian's poem which one of them is Layla and Majnun poem belongs to the famous poet of the Persian language - Nizami Ganjavi - and the other is Layla and Majnun poem which is a poem's work belongs to Ghasemi Gonabadi who is such a good theoritests of Nizami in the tenth century AD . He has been written his masnavi of Layla and Majnun to emulate by Nizami. In this article, after the introducing of two poems and offering one summary of them into prose, the comparison of these two works has been conducted in the terms of the structure, content and stylistic- language. In addition, this article has been mentioned just in passing to the othertheoritests oin the tenth century AD who imitate Layla and Majnun by Nizami. -

59The Poem of Nizami Ganjevi's Masnavi, Seven Beauties In

Fecha de presentación: diciembre, 2019, Fecha de Aceptación: enero, 2020, Fecha de publicación: marzo, 2020 THE POEM OF NIZAMİ GANJEVİ’S MASNAVİ, SEVEN BEAUTIES İN TASAVVUF CON- TEXT EL POEMA DE NIZAMİ GANJEVİ’S MASNAVİ, SİETE BELLAZAS EN EL CONTEXTO DE TASAVVUF Khuraman Hummatova1 E-mail: [email protected] ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3015-3107 59 1 National Academy of Sciences. Abserbayan. Suggested citation (APA, seventh edition) Hummatova, K. (2020). The poem of Nızami Ganjevi’s Masnavi, Seven Beautıes in Tasavvuf context. Revista Conrado, 16(73), 449-452. ABSTRACT RESUMEN Tasavvuf motives are seen openly in Nizami’s crea- Los motivos de Tasavvuf se ven abiertamente en la tivity particularly in his “Seven beauties” poem. But creatividad de Nizami, particularmente en su poe- the use of these motives dont give an opportunity ma “Siete bellezas”. Pero el uso de estos motivos no to consider presentation of tasaffuv-irvan thoughts da la oportunidad de considerar la presentación de of the poet as whole. That is why, Nizami ws a well pensamientos irlandeses de buen gusto del poeta known wisdom philosopher. As all researchers en su conjunto. Es por eso que Nizami fue un co- confirm, Nizami used the ideas which he conside- nocido filósofo de la sabiduría. Como todos los in- red satisfactory although Nizami attracted the con- vestigadores confirman, Nizami utilizó las ideas que temporary ideas of the cultural heritage pre him. consideró satisfactorias, aunque Nizami atrajo las Suphizm was a source of thoughts with its contem- ideas contemporáneas del patrimonio cultural que porary ideas and motives for Nizami. -

Fictional Storytelling in the Medieval Eastern Mediterranean and Beyond

iii Fictional Storytelling in the Medieval Eastern Mediterranean and Beyond Edited by CarolinaCupane BettinaKrönung LEIDEN |BOSTON For use by the Author only | © 2016 Koninklijke Brill NV ContentsContents v Contents List of Illustrations viii Notes on Contributors ix xiv Introduction: Medieval Fictional Story-Telling in the Eastern Mediterranean (8th–15th centuries AD): Historical and Cultural Context 1 Part 1 Of Love and Other Adventures 1 Mapping the Roots: The Novel in Antiquity 21 Massimo Fusillo 2 Romantic Love in Rhetorical Guise: The Byzantine Revival of the Twelfth Century 39 Ingela Nilsson 3 In the Mood of Love: Love Romances in Medieval Persian Poetry and their Sources 67 Julia Rubanovich 4 In the Realm of Eros: The Late Byzantine Vernacular Romance – Original Texts 95 Carolina Cupane 5 The Adaptations of Western Sources by Byzantine Vernacular Romances 127 Kostas Yiavis Part 2 Ancient and New Heroes 6 A Hero Without Borders: 1 Alexander the Great in Ancient, Byzantine and Modern Greek Tradition 159 Ulrich Moennig For use by the Author only | © 2016 Koninklijke Brill NV vi Contents 7 A Hero Without Borders: 2 Alexander the Great in the Syriac and Arabic Tradition 190 Faustina C.W. Doufikar-Aerts 8 A Hero Without Borders: 3 Alexander the Great in the Medieval Persian Tradition 210 Julia Rubanovich 9 Tales of the Trojan War: Achilles and Paris in Medieval Greek Literature 234 Renata Lavagnini 10 Shared Spaces: 1 Digenis Akritis, the Two-Blood Border Lord 260 Corinne Jouanno 11 Shared Spaces: 2 Cross-border Warriors in the Arabian Folk Epic 285 Claudia Ott Part 3 Wise Men and Clever Beasts 12 The Literary Life of a Fictional Life: Aesop in Antiquity and Byzantium 313 Grammatiki A.