Reading a Medieval Romance in Post-Revolutionary Tehran

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369, Fravardin & l FEZAN A IN S I D E T HJ S I S S U E Federation of Zoroastrian • Summer 2000, Tabestal1 1369 YZ • Associations of North America http://www.fezana.org PRESIDENT: Framroze K. Patel 3 Editorial - Pallan R. Ichaporia 9 South Circle, Woodbridge, NJ 07095 (732) 634-8585, (732) 636-5957 (F) 4 From the President - Framroze K. Patel president@ fezana. org 5 FEZANA Update 6 On the North American Scene FEZ ANA 10 Coming Events (World Congress 2000) Jr ([]) UJIR<J~ AIL '14 Interfaith PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF '15 Around the World NORTH AMERICA 20 A Millennium Gift - Four New Agiaries in Mumbai CHAIRPERSON: Khorshed Jungalwala Rohinton M. Rivetna 53 Firecut Lane, Sudbury, MA 01776 Cover Story: (978) 443-6858, (978) 440-8370 (F) 22 kayj@ ziplink.net Honoring our Past: History of Iran, from Legendary Times EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Roshan Rivetna 5750 S. Jackson St. Hinsdale, IL 60521 through the Sasanian Empire (630) 325-5383, (630) 734-1579 (F) Guest Editor Pallan R. Ichaporia ri vetna@ lucent. com 23 A Place in World History MILESTONES/ ANNOUNCEMENTS Roshan Rivetna with Pallan R. Ichaporia Mahrukh Motafram 33 Legendary History of the Peshdadians - Pallan R. Ichaporia 2390 Chanticleer, Brookfield, WI 53045 (414) 821-5296, [email protected] 35 Jamshid, History or Myth? - Pen1in J. Mist1y EDITORS 37 The Kayanian Dynasty - Pallan R. Ichaporia Adel Engineer, Dolly Malva, Jamshed Udvadia 40 The Persian Empire of the Achaemenians Pallan R. Ichaporia YOUTHFULLY SPEAKING: Nenshad Bardoliwalla 47 The Parthian Empire - Rashna P. -

Irreverent Persia

Irreverent Persia IRANIAN IRANIAN SERIES SERIES Poetry expressing criticism of social, political and cultural life is a vital integral part of IRREVERENT PERSIA Persian literary history. Its principal genres – invective, satire and burlesque – have been INVECTIVE, SATIRICAL AND BURLESQUE POETRY very popular with authors in every age. Despite the rich uninterrupted tradition, such texts FROM THE ORIGINS TO THE TIMURID PERIOD have been little studied and rarely translated. Their irreverent tones range from subtle (10TH TO 15TH CENTURIES) irony to crude direct insults, at times involving the use of outrageous and obscene terms. This anthology includes both major and minor poets from the origins of Persian poetry RICCARDO ZIPOLI (10th century) up to the age of Jâmi (15th century), traditionally considered the last great classical Persian poet. In addition to their historical and linguistic interest, many of these poems deserve to be read for their technical and aesthetic accomplishments, setting them among the masterpieces of Persian literature. Riccardo Zipoli is professor of Persian Language and Literature at Ca’ Foscari University, Venice, where he also teaches Conceiving and Producing Photography. The western cliché about Persian poetry is that it deals with roses, nightingales, wine, hyperbolic love-longing, an awareness of the transience of our existence, and a delicate appreciation of life’s fleeting pleasures. And so a great deal of it does. But there is another side to Persian verse, one that is satirical, sardonic, often obscene, one that delights in ad hominem invective and no-holds barred diatribes. Perhaps surprisingly enough for the uninitiated reader it is frequently the same poets who write both kinds of verse. -

Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nineteenth-Century Iran

publications on the near east publications on the near east Poetry’s Voice, Society’s Song: Ottoman Lyric The Transformation of Islamic Art during Poetry by Walter G. Andrews the Sunni Revival by Yasser Tabbaa The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Shiraz in the Age of Hafez: The Glory of Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century a Medieval Persian City by John Limbert by Zeynep Çelik The Martyrs of Karbala: Shi‘i Symbols The Tragedy of Sohráb and Rostám from and Rituals in Modern Iran the Persian National Epic, the Shahname by Kamran Scot Aghaie of Abol-Qasem Ferdowsi, translated by Ottoman Lyric Poetry: An Anthology, Jerome W. Clinton Expanded Edition, edited and translated The Jews in Modern Egypt, 1914–1952 by Walter G. Andrews, Najaat Black, and by Gudrun Krämer Mehmet Kalpaklı Izmir and the Levantine World, 1550–1650 Party Building in the Modern Middle East: by Daniel Goffman The Origins of Competitive and Coercive Rule by Michele Penner Angrist Medieval Agriculture and Islamic Science: The Almanac of a Yemeni Sultan Everyday Life and Consumer Culture by Daniel Martin Varisco in Eighteenth-Century Damascus by James Grehan Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey, edited by Sibel Bozdog˘an and The City’s Pleasures: Istanbul in the Eigh- Res¸at Kasaba teenth Century by Shirine Hamadeh Slavery and Abolition in the Ottoman Middle Reading Orientalism: Said and the Unsaid East by Ehud R. Toledano by Daniel Martin Varisco Britons in the Ottoman Empire, 1642–1660 The Merchant Houses of Mocha: Trade by Daniel Goffman and Architecture in an Indian Ocean Port by Nancy Um Popular Preaching and Religious Authority in the Medieval Islamic Near East Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nine- by Jonathan P. -

FEZANA Journal Do Not Necessarily Reflect the Feroza Fitch of Views of FEZANA Or Members of This Publication's Editorial Board

FEZANA FEZANA JOURNAL ZEMESTAN 1379 AY 3748 ZRE VOL. 24, NO. 4 WINTER/DECEMBER 2010 G WINTER/DECEMBER 2010 JOURJO N AL Dae – Behman – Spendarmad 1379 AY (Fasli) G Amordad – Shehrever – Meher 1380 AY (Shenshai) G Shehrever – Meher – Avan 1380 AY (Kadimi) CELEBRATING 1000 YEARS Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh: The Soul of Iran HAPPY NEW YEAR 2011 Also Inside: Earliest surviving manuscripts Sorabji Pochkhanawala: India’s greatest banker Obama questioned by Zoroastrian students U.S. Presidential Executive Mission PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 24 No 4 Winter / December 2010 Zemestan 1379 AY 3748 ZRE President Bomi V Patel www.fezana.org Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor 2 Editorial [email protected] Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar Dolly Dastoor Assistant to Editor: Dinyar Patel Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, [email protected] 6 Financial Report Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, www.khanizadeh.info Cover design: Feroza Fitch, 8 FEZANA UPDATE-World Youth Congress [email protected] Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia Columnists: Hoshang Shroff: [email protected] Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi : [email protected] 12 SHAHNAMEH-the Soul of Iran Yezdi Godiwalla: [email protected] Behram Panthaki::[email protected] Behram Pastakia: [email protected] Mahrukh Motafram: [email protected] 50 IN THE NEWS Copy editors: R Mehta, V Canteenwalla Subscription Managers: Arnavaz Sethna: [email protected]; -

Summer/June 2014

AMORDAD – SHEHREVER- MEHER 1383 AY (SHENSHAI) FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA TABESTAN 1383 AY 3752 Z VOL. 28, No 2 SUMMER/JUNE 2014 ● SUMMER/JUNE 2014 Tir–Amordad–ShehreverJOUR 1383 AY (Fasli) • Behman–Spendarmad 1383 AY Fravardin 1384 (Shenshai) •N Spendarmad 1383 AY Fravardin–ArdibeheshtAL 1384 AY (Kadimi) Zoroastrians of Central Asia PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Copyright ©2014 Federation of Zoroastrian Associations of North America • • With 'Best Compfiments from rrhe Incorporated fJTustees of the Zoroastrian Charity :Funds of :J{ongl(pnffi Canton & Macao • • PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 28 No 2 June / Summer 2014, Tabestan 1383 AY 3752 Z 92 Zoroastrianism and 90 The Death of Iranian Religions in Yazdegerd III at Merv Ancient Armenia 15 Was Central Asia the Ancient Home of 74 Letters from Sogdian the Aryan Nation & Zoroastrians at the Zoroastrian Religion ? Eastern Crosssroads 02 Editorials 42 Some Reflections on Furniture Of Sogdians And Zoroastrianism in Sogdiana Other Central Asians In 11 FEZANA AGM 2014 - Seattle and Bactria China 13 Zoroastrians of Central 49 Understanding Central 78 Kazakhstan Interfaith Asia Genesis of This Issue Asian Zoroastrianism Activities: Zoroastrian Through Sogdian Art Forms 22 Evidence from Archeology Participation and Art 55 Iranian Themes in the 80 Balkh: The Holy Land Afrasyab Paintings in the 31 Parthian Zoroastrians at Hall of Ambassadors 87 Is There A Zoroastrian Nisa Revival In Present Day 61 The Zoroastrain Bone Tajikistan? 34 "Zoroastrian Traces" In Boxes of Chorasmia and Two Ancient Sites In Sogdiana 98 Treasures of the Silk Road Bactria And Sogdiana: Takhti Sangin And Sarazm 66 Zoroastrian Funerary 102 Personal Profile Beliefs And Practices As Shown On The Tomb 104 Books and Arts Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor, editor(@)fezana.org AMORDAD SHEHREVER MEHER 1383 AY (SHENSHAI) FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar TABESTAN 1383 AY 3752 Z VOL. -

Iran (Persia) and Aryans Part - 1

INDIA (BHARAT) - IRAN (PERSIA) AND ARYANS PART - 1 Dr. Gaurav A. Vyas This book contains the rich History of India (Bharat) and Iran (Persia) Empire. There was a time when India and Iran was one land. This book is written by collecting information from various sources available on the internet. ROOTSHUNT 15, Mangalyam Society, Near Ocean Park, Nehrunagar, Ahmedabad – 380 015, Gujarat, BHARAT. M : 0091 – 98792 58523 / Web : www.rootshunt.com / E-mail : [email protected] Contents at a glance : PART - 1 1. Who were Aryans ............................................................................................................................ 1 2. Prehistory of Aryans ..................................................................................................................... 2 3. Aryans - 1 ............................................................................................................................................ 10 4. Aryans - 2 …............................………………….......................................................................................... 23 5. History of the Ancient Aryans: Outlined in Zoroastrian scriptures …….............. 28 6. Pre-Zoroastrian Aryan Religions ........................................................................................... 33 7. Evolution of Aryan worship ....................................................................................................... 45 8. Aryan homeland and neighboring lands in Avesta …...................……………........…....... 53 9. Western -

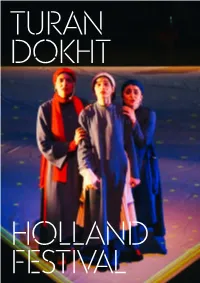

Turan-Dokht-Programme.Pdf

TURAN DOKHT HOLLAND FESTIVAL TURAN DOKHT Aftab Darvishi Miranda Lakerveld Nilper Orchestra thanks to production partner patron coproduction CONTENT Info & context Credits Synopsis Notes A conversation with Miranda Lakerveld About the artists Friends Holland Festival 2019 Join us Colophon INFO CONTEXT date & starting time introduction Wed 5 June 2019, 8.30 pm by Peyman Jafari Thu 6 June 2019, 8.30 pm 7.45 pm venue Hamid Dabashi – Persian culture on Muziekgebouw The Global Scene Thu 6 Juni, 4 pm running time Podium Mozaïek 1 hour 20 minutes no interval language Farsi and Italian with English and Dutch surtitles CREDITS composition production Aftab Darvishi World Opera Lab, Jasper Berben libretto, direction with support of Miranda Lakerveld Fonds Podiumkunsten, Gieskes-Strijbis Fonds, Amsterdams Fonds voor de Kunst, conductor Nederlandse Ambassade Tehran Navid Gohari world premiere video 24 February 2019 Siavash Naghshbandi Azadi Tower, Tehran light Turan Dokht is inspired by the Haft Bart van den Heuvel Peykar of Nizami Ganjavi and Turandot by Giacomo Puccini. The fragments of costumes Puccini’s Turandot are used with kind per- Nasrin Khorrami mission of Ricordi Publishing House. dramaturgy, text advice All the flights that are made for this Asghar Seyed-Gohrab project are compensated for their CO2 emissions. vocals Ekaterina Levental (Turan Dokht), websites Arash Roozbehi (The unknown prince), World Opera Lab Sarah Akbari, Niloofar Nedaei, Miranda Lakerveld Tahere Hezave Aftab Darvishi acting musicians Yasaman Koozehgar, Yalda Ehsani, Mahsa Rahmati, Anahita Vahediardekani music performed by Behzad Hasanzadeh, voice/kamanche Mehrdad Alizadeh Veshki, percussion Nilper Orchestra SYNOPSIS The seven beauties from Nizami’s Haft Peykar represent the seven continents, the seven planets and the seven colours. -

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Studia Iranica Upsaliensia 28

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Studia Iranica Upsaliensia 28 Traces of Time The Image of the Islamic Revolution, the Hero and Martyrdom in Persian Novels Written in Iran and in Exile Behrooz Sheyda ABSTRACT Sheyda, B. 2016. Traces of Time. The Image of the Islamic Revolution, the Hero and Martyrdom in Persian Novels Written in Iran and in Exile. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Studia Iranica Upsaliensia 28. 196 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 978-91-554-9577-0 The present study explores the image of the Islamic Revolution, the concept of the hero, and the concept of martyrdom as depicted in ten post-Revolutionary Persian novels written and published in Iran compared with ten post-Revolutionary Persian novels written and published in exile. The method is based on a comparative analysis of these two categories of novels. Roland Barthes’s structuralism will be used as the theoretical tool for the analysis of the novels. The comparative analysis of the two groups of novels will be carried out within the framework of Foucault’s theory of discourse. Since its emergence, the Persian novel has been a scene for the dialogue between the five main discourses in the history of Iran since the Constitutional Revolution; this dialogue, in turn, has taken place within the larger framework of the dialogue between modernity and traditionalism. The main conclusion to be drawn from the present study is that the establishment of the Islamic Republic has merely altered the makeup of the scene, while the primary dialogue between modernity and traditionalism continues unabated. This dialogue can be heard in the way the Islamic Republic, the hero, and martyrdom are portrayed in the twenty post-Revolutionary novels in this study. -

The Academic Resume of Dr. Gholamhossein Gholamhosseinzadeh

The Academic Resume of Dr. Gholamhossein Gholamhosseinzadeh Professor of Persian Language and Literature in Tarbiat Modarres University Academic Background Degree The end date Field of Study University Ferdowsi Persian Language University of ١٩٧٩/٤/٤ BA and Literature Mashhad Persian Language Tarbiat Modarres and Literature University ١٩٨٩/٢/٤ MA Persian Language Tarbiat Modarres and Literature University ١٩٩٥/٣/١٥ .Ph.D Articles Published in Scientific Journals Year of Season of Row Title Publication Publication Explaining the Reasons for Explicit Adoptions Summer ٢٠١٨ of Tazkara-Tul-Aulia from Kashif-Al-Mahjoub ١ in the Sufis Karamat Re-Conjugation of Single Paradigms of Middle Spring ٢٠١٧ Period in the Modern Period (Historical ٢ Transformation in Persian Language) ٢٠١٧ Investigating the Effect of the Grammatical Elements and Loan Words of Persian Language Spring ٣ on Kashmiri Language ٢٠١٧ The Course of the Development and Spring Categorization of the Iranian Tradition of ٤ Writing Political Letter of Advice in the World Some Dialectal Elements in Constructing t he Spring ٢٠١٦ ٥ Verbs in the Text of Creation ٢٠١٦ The Coding and the Aspect: Two Distinctive Fall ٦ ١ Year of Season of Row Title Publication Publication Factors in the Discourse Stylistics of Naser Khosrow’s Odes ٢٠١٦ Conceptual Metaphor: Convergence of Summer ٧ Thought and Rhetoric in Naser Khosrow's Odes ٢٠١٦ A Comparative Study of Linguistic and Stylistic Features of Samak-E-Ayyar, Hamzeh- Fall ٨ Nameh and Eskandar-Nameh ٢٠١٦ The Effect of Familiarity with Old Persian -

88 the Impact of the French Literature on the Modern Persian Literature

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research ISSN: 2455-2070; Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 www.socialresearchjournals.com Volume 2; Issue 12; December 2016; Page No. 88-95 The impact of the French literature on the modern Persian literature Mukhtar Ahmed Research Scholar, Centre for Persian and Central Asian Studies, School of Language, Literature and Culture Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India Abstract The social and cultural interactions between Persia and France had been established since accession of the Safavids in Iran. The influx of foreigners into Iran and Iranians into West caused a new sort of trend in European literatures and Persian literature. Travelers played a leading role in bringing them closer academically and culturally. Iran’s interaction with the West in general and with the France in particular resulted in the form of a revolution on political, social and literary levels. The establishment of Dar-ul-Funun necessitated the translations of books from the western world. Persian literature, which had deteriorated since Mongol times in Iran, had started its revival in the early nineteenth century. The primary reform in prose literature took place ‘in the official correspondence, led by two of the greatest prime ministers Persian has ever produced: the Qa’im Maqam Farahani and the Amir Kabir. Later innovations came from two political and literary figures: Mirza Malkom Khan and Abdul Rahim Talibuff’. After that Jamalzade, Hedayat and many more writers who visited France or any other western country and became familiar with their literatures wrote some remarkable and path-breaking books that also revolutionized the whole corpus of Persian prose literature. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Reza Farokhfal Address in the US: 1350 20th St., Apt. A-54 Boulder, CO, 80302 Cell: 720)292-7348 [email protected] [email protected] Address in Canada: 6384 Rue de L’Aiglon, Laval (Montreal), QC, H7L 4W2, Canada Tel: (450) 963-3096 Nationality Iranian –Canadian LANGUAGES Persian (mother tongue) English (writing, reading, speaking, comprehension) Classical Arabic (reading, comprehension) French (reading, comprehension) Education M.A. in Communications, Concordia University, Montreal, Canada B.A. in History, Pahlavi University, Shiraz, Iran Professional affiliation As a language instructor: Member of American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) Member of National Council of Less Commonly Taught Languages (NCOLCTL) Member of American association of Teachers of Persian (AATP) CLS study abroad/fellowship advisor As a writer: Present member, Pen Canada Present member, the Writers League of Iran Member of the board of directors of Iran Editors Association (1992-95) Teaching experience 2008-2016 Instructor and coordinator of the Persian program, Department of Asian Languages and Civilizations, UC- Boulder 2006- 2008 Lecturer in Persian, Department of languages and Cultures of Asia UW-Madison Summer 2007 Lecturer in Persian, Persian Immersion Program, UW- Lacrosse Summer 2006 Lecturer in Persian, Persian Immersion Program, UW- Lacrosse 2001- 2005 Lecturer in Persian, Institute of Islamic Studies, McGill University, Montreal Recent activities 2016 Invited by Stanford University (Dept. Iranian studies) for delivering a lecture at the conference “A Portrait of Houshang Golshiri in Texts, Contexts, Manuscripts and Fragments” held on January 14th 2016. 2015-2016 Coordinating the project “A Digital Concise Persian Vocal Dictionary”, in collaboration with CU-Boulder's Anderson Language Technology Centre. -

The Nizami of Azerbaijan and the World

Great people THE NIZAMI OF AZERBAIJAN AND THE WORLD Rafael HUSEYNOV Doctor of Philology, Professor, Corresponding Member of the ANAS ON SATURDAY, 30 SEPTEMBER 1139, A VERY SERIOUS EVENT HAPPENED IN THE HISTORY OF THE EARTH. IT WAS ONE OF THE MOST DEVASTAT ING EARTHQUAKES IN WORLD HIS TORY AND TURNED THE EARTH UP SIDE DOWN. MEDIEVAL HISTORIANS RECORDED THAT THIS EARTHQUAKE, WHICH HAPPENED IN THE CITY OF GANJA, HAD NO ANALOGUES FOR THE DEVASTATION IT CAUSED. he earthquake totally destroyed Ganja. But in its stead, it created Ta natural wonder like Goygol. The earthquake killed tens of thou- sands of people. But to compen- sate for all those losses, nature gave Azerbaijan and the world an unusual child in 1141. A genius poet and phi- losopher, who became known as Nizami Ganjavi later, whose pieces woke people’s spirit and thoughts for centuries and whose works became a school, was born. Nizami Ganjavi has long ceased to be only Azerbaijan’s child. His lit- “Nizami in his native Ganja” by Eyyub Mammadov 38 www.irs-az.com erary heritage is part of the treasury born in the city of Qom in Iran. is still originally from Ganja of humanity’s most valuable assets, while he himself rose to such a level Cho dorr garcheh dar bahr-e Ganjeh Some sources (for example, that he became a child of all peoples qomam Daulatshah Samarqandi, 15th centu- and humanity. In his lifetime, Niza- Vali az gahestane shahre Qomam ry) say that Nizami had a poet broth- mi Ganjavi believed that his works er named Givami Mutarrizi.