James G. Colbert Oral History Interview—4/16/1964 Administrative Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Staff of House Committee on the Judiciary, 84Th Congress, Report On

Fordham Law School FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History Congressional Materials Twenty-Fifth Amendment Archive 1-31-1956 Staff of ouH se Committee on the Judiciary, 84th Congress, Report on Presidential Inability Staff of the ouH se Committee on the Judiciary Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ twentyfifth_amendment_congressional_materials Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Staff of the ousH e Committee on the Judiciary, "Staff of ousH e Committee on the Judiciary, 84th Congress, Report on Presidential Inability" (1956). Congressional Materials. 15. http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/twentyfifth_amendment_congressional_materials/15 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Twenty-Fifth Amendment Archive at FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Congressional Materials by an authorized administrator of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 84th2d SessionOongre} I HOU8BOS COMXXTTEOMITI PRUNXKN PRESIDENTIAL INABILITY COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary UVNTED STAThT GOVI3040 PRinTING OlFIC2 "u WA5 • as HoN COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY EMANUEL CELLER, Now York, Calrman FRANCIS 2. WALTER, Pennsylvania CHAUNCEY W. REED, Illinois THOMAS 3. LANE, Massachuaetts KENNETH B. KEATING, Now York MICHAEL A. FEIGHAN, Ohio WILLIAM M. McCULLOCH, Ohio FRANK CHELF, Kentucky RUTH THOMPSON, Michigan IEDWIN E. WILLIS, Louisiana PATRICK J. HILLINOS, California JAMES B.FRAZIER, Ja., Tennessee S8IEPARD 3, CRUMPACKER, It., Indiana PETER W. RODINO, J.., New Jersey -°*WILLfAM E. MILLER, New York WOODROW W. -

Charles Bartlett Interviewer: Fred Holborn Date of Interview: January 6, 1965 Place of Interview: Washington, D.C

Charles Bartlett Oral History Interview – JFK #1, 1/6/1965 Administrative Information Creator: Charles Bartlett Interviewer: Fred Holborn Date of Interview: January 6, 1965 Place of Interview: Washington, D.C. Length: 91 pp. Biographical Note Bartlett, Washington correspondent for the Chattanooga Times from 1948 to 1962, columnist for the Chicago Daily News, and personal friend of John F. Kennedy (JFK), discusses his role in introducing Jacqueline Bouvier to JFK, JFK’s relationship with Lyndon Baines Johnson, and JFK’s Cabinet appointments, among other issues. Access Open. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed October 11, 1983, copyright of these materials has been assigned to United States Government. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. The copyright law extends its protection to unpublished works from the moment of creation in a tangible form. Direct your questions concerning copyright to the reference staff. -

Henry Cabot Lodge

1650 Copyright by CLP Research Partial Genealogy of the Lodges Main Political Affiliation: (of Massachusetts & Connecticut) 1763-83 1789-1823 Federalist ?? 1824-33 National Republican ?? 1700 1834-53 Whig ?? 1854- Republican 1750 Giles Lodge (1770-1852); (planter/merchant) (Emigrated from London, England to Santo Domingo, then Massachusetts, 1791) See Langdon of NH = Abigail Harris Langdon Genealogy (1776-1846) (possibly descended from John, son of John Langdon, 1608-97) 1800 10 Others John Ellerton Lodge (1807-62) (moved to New Orleans, 1824); (returned to Boston with fleet of merchant ships, 1835) (engaged in trade with China); (died in Washington state) See Cabot of MA = Anna Sophia Cabot Genealogy (1821-1901) Part I Henry Cabot Lodge (1850-1924) 1850 (MA house, 1880); (ally of Teddy Roosevelt) See Davis of MA (US House, 1887-93); (US Senate, 1893-1924; opponent of League of Nations) Genealogy Part I = Ann Cabot Mills Davis (1851-1914) See Davis of MA Constance Davis George Cabot Lodge Genealogy John Ellerton Lodge Cabot Lodge (1873-1909) Part I (1878-1942) (1872-after 1823) = Matilda Elizabeth Frelinghuysen Davis (1875-at least 1903) (Oriental art scholar) = Col. Augustus Peabody Gardner = Mary Connally (1885?-at least 1903) (1865-1918) Col. Henry Cabot Lodge Cmd. John Davis Lodge Helena Lodge 1900(MA senate, 1900-01) (from Canada) (US House, 1902-17) (1902-85); (Rep); (newspaper reporter) (1903-85); (Rep) (1905-at least 1970) (no children) (WWI/US Army) (MA house, 1933-36); (US Senate, 1937-44, 1947-53; (movie actor, 1930s-40s); -

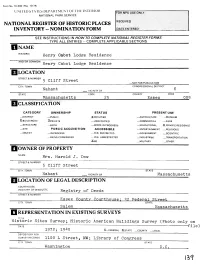

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATHS DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Henry Cabot Lodge Residence AND/OR COMMON Henry Cabot Lodge Residence 5 Cliff Street .NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Nahant VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 25 Essex 009 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC XOCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK _ STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X.PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE _ ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS _OBJECT _IN PROCESS _YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION -XNO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mrs. Harold J. Dow STREET & NUMBER 5 Cliff Street CITY, TOWN STATE Nahant VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER Essex County Courthouse: ^2 Federal Street CITY, TOWN STATE Salem Massachusetts I REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic Sites Survey; Historic American Buildings Survey (Photo only on DATE ————————————————————————————————————file) 1972; 19^0 X_FEDERAL 2LSTATE _COUNTY _J_OCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS 1100 L Street, NW; Library of Congress Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT -DETERIORATED —UNALTERED 3C ORIGINAL SITE X_QOOD —RUINS X_ALTERED _MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE This two-story, hip-roofed, white stucco-^covered, lavender- trimmed, brick villa is the only known extant residence associated with Henry Cabot Lodge. -

Mr. Tuck's File of Letters from Jennifer M

Mr. Tuck’s File of Letters from Jennifer M. Allocca’s research; additional notes by Dan Rothman The “Bulletin of the Essex Institute” (Volume XX. 1888. Salem, Mass. Printed 1889.) describes a September 1887 presentation to the Institute by Mr. J. D. Tuck, which provides additional information about the New Boston counterfeiters. https://books.google.com/books?id=BKQUAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA28&lpg=PA28 Joseph Dane Tuck (1817-1900) was a tailor who was born in Beverly, MA and died in that town. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Essex_Institute tells us that the Essex Institute (1848–1992) in Salem, Massachusetts, was “a literary, historical and scientific society.” It maintained a museum, library, historic houses; arranged educational programs; and issued numerous scholarly publications. In 1992 the institute merged with the Peabody Museum of Salem to form the Peabody Essex Museum. The correspondence in Mr. Tuck’s file gives us an interesting picture of how Boston-area bankers struggled with the expensive problem of counterfeit bills. Representatives of the banks whose notes had been counterfeited met to discuss what should be done. They feared that Mr. Peasley (or Peaslee) who had engraved the plates would flee when he learned of the arrest of the New Boston counterfeiters. The bankers knew that Stephen Burroughs, the most famous counterfeiter of his day, was busy producing paper currency in Stanstead, Quebec (in the Eastern Townships of Lower Canada), just a few miles north of the Vermont border. How could they apprehend him and place him “in the way to the Gallows”? They worried that at least one of the bailiffs they might send to Stanstead to collect evidence and arrest the counterfeiters was himself a member of the gang. -

Jackson J. Holtz Interviewer: David Hern Date of Interview: May 7, 1964 Place of Interview: Boston, Massachusetts Length: 13 Pages

Jackson J. Holtz Oral History Interview – JFK#1, 05/07/1964 Administrative Information Creator: Jackson J. Holtz Interviewer: David Hern Date of Interview: May 7, 1964 Place of Interview: Boston, Massachusetts Length: 13 pages Biographical Note Holtz was the Vice Chairman of John F. Kennedy’s [JFK] 1952 Senate campaign. In this interview Holtz discusses his relationship with JFK; working on JFK’s 1952 Senate campaign; comparisons between JFK and Henry Cabot Lodge during the 1952 Senate race; JFK, Holtz, and the Algerian crisis; JFK’s involvement with Holtz’s 1954 and 1956 congressional campaigns; discussing Senator Joseph McCarthy with JFK; the 1956 Democratic National Convention; and JFK and Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis’ wedding, among other issues. Access Open. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed September 4, 1973, copyright of these materials has been assigned to the United States Government. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. -

Annual Report of the Town Officers of Wakefield Massachusetts

133rd ANNUAL REPORT OF THE TOWN OFFICERS OF WAKEFIELD, MA55. Financial Year Ending December Thirty-first Nineteen hundred and Forty-four ALSO THE TOWN CLERICS RECORDS OF THL BIRTHS, MARRIAGES AND DEATHS During the Year 1944 WAKEFIELD Town Officers, 1944-45 Selectmen *L. Wallace Sweetser, Chairman — William R. Lindsay, Chairman William G. Dill, Secretary Orrin J. Hale Richard M. Davis * Resigned as Chairman. Town Clerk Charles F. Young Assistant Town Clerk Marion B. Connell Town Treasurer John I. Preston Tax Collector Carl W. Sunman Town Accountant Charles C. Cox Moderator Thomas G. O'Connell Assessors George E. Blair, Chairman Term Expires March 1947 Leo F. Douglass, Secretary " " " 1945 George H. Stout " " " 1946 Municipal Light Commissioners Marcus Beebe, 2nd, Chairman Term Expires March 1947 Theodore Eaton, Secretary " " " 1945 Curtis L. Sopher " " " 1946 Water and Sewerage Board Sidney F. Adams, Chairman Term Expires March 1946 " -"^ :«.. John N. Bill, Secretary - • 1947 " " Herman G. Dresser " 1945 TOWN OF WAKEFIELD Board of Public Welfare Helen M. Randall, Chairman Term Expires March 1945 M. Leo Conway, Secretary « 1946 Harold C. Robinson " 1946 Peter Y. Myhre « 1945 J. Edward Dulong 1947 School Committee Patrick H. Tenney, Chairman Term Expires March 1946 << « Eva Gowing Ripley, Secretary " 1946 Mary Louise Tredinnick «< « " 1945 James M. Henderson n « " 1945 Paul A. Saunders tt it " 1947 M tt Walter C. Hickey " 1947 Trustees Lucius Beebe Memorial Library Hervey J. Skinner, Chairman Term Expires March 1946 < tt Florence I. Bean, Secretary " 1946 John J. Round < tt " 1946 Albert W. Rockwood « tt " 1947 Dr. Richard Dutton < << " 1947 Alice W. Wheeler < it " 1947 Walter C. -

Henry Cabot Lodge Collection: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8hm5fk8 No online items Henry Cabot Lodge Collection: Finding Aid Finding aid prepared by Gayle M. Richardson, July 8, 2010. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2129 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2010 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Henry Cabot Lodge Collection: mssHM 73270-73569 1 Finding Aid Overview of the Collection Title: Henry Cabot Lodge Collection Dates (inclusive): 1871-1925 Collection Number: mssHM 73270-73569 Creator: Lodge, Henry Cabot, 1850-1924. Extent: 300 pieces in 6 boxes Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2129 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection consists of correspondence and a small amount of printed ephemera of American statesman Henry Cabot Lodge (1850-1924). The majority of the letters are by Lodge; these include a very small number of personal letters but are mainly letters by Lodge to other political leaders of the time or to his Massachusetts constituents. Language: English. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. The responsibility for identifying the copyright holder, if there is one, and obtaining necessary permissions rests with the researcher. -

Names and Addresses of Living Bachelors and Masters of Arts, And

id 3/3? A3 ^^m •% HARVARD UNIVERSITY. A LIST OF THE NAMES AND ADDRESSES OF LIVING ALUMNI HAKVAKD COLLEGE. 1890, Prepared by the Secretary of the University from material furnished by the class secretaries, the Editor of the Quinquennial Catalogue, the Librarian of the Law School, and numerous individual graduates. (SKCOND YEAR.) Cambridge, Mass., March 15. 1890. V& ALUMNI OF HARVARD COLLEGE. \f *** Where no StateStat is named, the residence is in Mass. Class Secretaries are indicated by a 1817. Hon. George Bancroft, Washington, D. C. ISIS. Rev. F. A. Farley, 130 Pacific, Brooklyn, N. Y. 1819. George Salmon Bourne. Thomas L. Caldwell. George Henry Snelling, 42 Court, Boston. 18SO, Rev. William H. Furness, 1426 Pine, Philadelphia, Pa. 1831. Hon. Edward G. Loring, 1512 K, Washington, D. C. Rev. William Withington, 1331 11th, Washington, D. C. 18SS. Samuel Ward Chandler, 1511 Girard Ave., Philadelphia, Pa. 1823. George Peabody, Salem. William G. Prince, Dedham. 18S4. Rev. Artemas Bowers Muzzey, Cambridge. George Wheatland, Salem. 18S5. Francis O. Dorr, 21 Watkyn's Block, Troy, N. Y. Rev. F. H. Hedge, North Ave., Cambridge. 18S6. Julian Abbott, 87 Central, Lowell. Dr. Henry Dyer, 37 Fifth Ave., New York, N. Y. Rev. A. P. Peabody, Cambridge. Dr. W. L. Russell, Barre. 18S7. lyEpes S. Dixwell, 58 Garden, Cambridge. William P. Perkins, Wa}dand. George H. Whitman, Billerica. Rev. Horatio Wood, 124 Liberty, Lowell. 1828] 1838. Rev. Charles Babbidge, Pepperell. Arthur H. H. Bernard. Fredericksburg, Va. §3PDr. Henry Ingersoll Bowditch, 113 Boylston, Boston. Rev. Joseph W. Cross, West Boylston. Patrick Grant, 3D Court, Boston. Oliver Prescott, New Bedford. -

New Light on the First Bank of the United States 1 the First

NEW LIGHT ON THE FIRST BANK OF THE UNITED STATES1 HE FIRST Bank of the United States, although semi-public in Tcharacter, has always remained an obscure element in our early national history. Established by Congress in 1791 on the recommendation of Alexander Hamilton, the Bank constituted an integral and essential part of the system proposed by that brilliant statesman of industrial capitalism for the revival and support of public credit and for the promotion of business enterprise.2 For twenty years, until its non-recharter and dissolution in 1811, it functioned and flourished, not merely as "an indispensable engine in the admin- istration of the finances," as Hamilton pronounced it, but also as the mainspring and regulator of the whole American business world. It was likewise an important political issue between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans on several occasions. Yet little is known of its inner history. Historians and economists alike have regretted the scantiness of data relating to its operations. With the exception of a few reports on Treasury deposits, the general public and even the Federal legislature had no knowledge of its condition until just prior to the expiration of the charter when Secre- tary Gallatin submitted several statements to Congress. No suspen- sion of specie payments, no really catastrophic financial panic, no fail- ure to pay dividends occurred to cause a demand for throwing the spotlight of "pitiless publicity" upon the institution. The career of the second Bank of the United States was a sharp contrast in this re- spect.3 But despite its shroud of secrecy, the first Bank seems to have had nothing to conceal. -

Public Officers of the COMMONWEALTH of MASSACHUSETTS

1953-1954 Public Officers of the COMMONWEALTH of MASSACHUSETTS c * f h Prepared and printed under authority of Section 18 of Chapter 5 of the General Laws, as most recently amended by Chapter 811 of the Acts of 1950 by IRVING N. HAYDEN Clerk of the Senate AND LAWRENCE R. GROVE Clerk of the House of Representatives SENATORS AND REPRESENTATIVES FROM MASSACHUSETTS IN THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES U. S. SENATE LEVERETT SALTONSTALL Smith Street, Dover, Republican. Born: Newton, Sept. 1, 1892. Education: Noble & Greenough School '10, Harvard College A.B. '14, Harvard Law School LL.B. '17. Profession: Lawyer. Organizations: Masons, P^lks. American Le- gion, Veterans of Foreign Wars, Ancient and Honorable Artillery. 1920- Public office : Newton Board of Aldermen '22, Asst. District-Attornev Middlesex County 1921-'22, Mass. House 1923-'3G (Speaker 1929-'36), Governor 1939-'44, United States Senate l944-'48 (to fill vacancy), 1949-'54. U. S. SENATE JOHN FITZGERALD KENNEDY 122 Bowdoin St., Boston, Democrat. Born: Brookline, May 29, 1917. Education: Harvard University, London School of Economics LL.D., Notre Dame University. Organizations: Veterans of Foreign Wars, American Legion, AMVETS, D.A.V., Knights of Columbus. Public office: Representative in Congress (80th ( - to 82d 1947-52, United states Senate 1 .>:>:; '58. U. S. HOUSE WILLIAM H. BATES 11 Buffum St., Salem, Gth District, Republican. Born: Salem, April 26, 1917. Education: Salem High School, Worcester Academy, Brown University, Harvard Gradu- ate School of Business Administration. Occupation: Government. Organizations: American Legion, Veterans of Foreign Wars. Public Office: Lt. Comdr. (Navy), Repre- sentative in Congress (81st) 1950 (to fill vacancy), (82d and 83d) 1951-54. -

The Cabots of Boston - Early Aviation Enthusiasts

NSM Historical Journal Summer 2018 National Soaring Museum Historical Journal Summer 2018 Table of Contents pages 1-9 British Gliding History pages 10-11 Germany’s Gift to Sporting America pages 12-14 Our First Soaring Flight in America pages 15-18 The Cabots of Boston - Early Aviation Enthusiasts Front Cover: First British Gliding Competition 1922 Back Cover: Gunther Groenhoff, Robert Kronfeld and Wolf Hirth in 1931 1 NSM Journal Summer 2018 Editor - The text for the following article was extracted from a book by Norman Ellison, British Gliders and Sailplanes 1922-1970. Mr. Ellison divides his history of British gliding into four segments: 1849-1908; 1908-1920; 1920-1929; and 1929-present (1970) British Gliding History The history of motorless flight in Britain can be divided into four periods. The first period up to 1908 started way back in 1849 when Sir George Cayley persuaded a boy to fly in one of his small gliders. Later, in 1853, Sir George's coachman was launched across a small valley at Brompton, near Scarborough. This experiment terminated abruptly when the craft reached the other side of the valley, and the frightened coachman stepped from the wreckage and addressed his employer with the now famous words "Sir George, I wish to hand in my notice". Cayley’s Glider Sir George Cayley Further would-be aviators carried out many other Percy Pilcher experiments over the years that followed, including Percy Pilcher's many glides at various places up and down the country until his death in 1899. The first period came to an end when S.