FLAGS, IDENTITY, MEMORY : Critiquing the Public Narrative Through Color

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record—Senate S3730

S3730 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE June 12, 2018 I know each of my colleagues can tes- On Christmas Eve last year, the sen- gressional review of certain regulations tify to the important roles military in- ior Senator from Montana took to the issued by the Committee on Foreign Invest- stallations play in communities all Bozeman Daily Chronicle with a piece ment in the United States. across our country. My fellow Ken- titled ‘‘Tax bill a disastrous plan, fails Reed/Warren amendment No. 2756 (to amendment No. 2700), to require the author- tuckians and I take great pride in Fort Montana and our future.’’ Quite a pro- ization of appropriation of amounts for the Campbell, Fort Knox, and the Blue nouncement. It reminded me of the development of new or modified nuclear Grass Army Depot. We are proud that Democratic leader of the House. She weapons. Kentucky is home base to many out- said our plan to give tax cuts to mid- Lee amendment No. 2366 (to the language standing units, such as the 101st Air- dle-class families and businesses would proposed to be stricken by amendment No. borne Division and those of Kentucky’s bring about ‘‘Armageddon.’’ Armaged- 2282), to clarify that an authorization to use Air and Army National Guard units. don. military force, a declaration of war, or any In our State, as in every State, the How are these prognostications hold- similar authority does not authorize the de- tention without charge or trial of a citizen military’s presence anchors entire ing up? The new Tax Code is causing or lawful permanent resident of the United communities and offers a constant re- Northwestern Energy to pass along States. -

Mapping the Body-Politic of the Raped Woman and the Nation in Bangladesh

gendered embodiments: mapping the body-politic of the raped woman and the nation in Bangladesh Mookherjee, Nayanika . Feminist Review, suppl. War 88 (Apr 2008): 36-53. Turn on hit highlighting for speaking browsers Turn off hit highlighting Other formats: Citation/Abstract Full text - PDF (206 KB) Abstract (summary) Translate There has been much academic work outlining the complex links between women and the nation. Women provide legitimacy to the political projects of the nation in particular social and historical contexts. This article focuses on the gendered symbolization of the nation through the rhetoric of the 'motherland' and the manipulation of this rhetoric in the context of national struggle in Bangladesh. I show the ways in which the visual representation of this 'motherland' as fertile countryside, and its idealization primarily through rural landscapes has enabled a crystallization of essentialist gender roles for women. This article is particularly interested in how these images had to be reconciled with the subjectivities of women raped during the Bangladesh Liberation War (Muktijuddho) and the role of the aestheticizing sensibilities of Bangladesh's middle class in that process. [PUBLICATION ABSTRACT] Show less Full Text Translate Turn on search term navigation introduction There has been much academic work outlining the complex links between women and the nation (Yuval-Davis and Anthias, 1989; Yuval-Davis, 1997; Yuval-Davis and Werbner, 1999). Women provide legitimacy to the political projects of the nation in particular social and historical contexts (Kandiyoti, 1991; Chatterjee, 1994). This article focuses on the gendered symbolization of the nation through the rhetoric of the 'motherland' and the manipulation of this rhetoric in the context of national struggle in Bangladesh. -

Bishop Barron Blazon Texts

THE FORMAL BLAZON OF THE EPISCOPAL COAT OF ARMS OF ROBERT E. BARRON, S.T.D. D.D. K.H.S. TITULAR BISHOP OF MACRIANA IN MAURETANIA AUXILIARY TO THE METROPOLITAN OF LOS ANGELES PER PALE OR AND MURREY AN OPEN BOOK PROPER SURMOUNTED OF A CHI RHO OR AND ENFLAMED COUNTERCHANGED, ON A CHIEF WAVY AZURE A PAIR OF WINGS ELEVATED, DISPLAYED AND CONJOINED IN BASE OR CHARGED WITH A FLEUR-DE-LIS ARGENT AND FOR A MOTTO « NON NISI TE DOMINE » THE OFFICE OF AUXILIARY BISHOP The Office of Auxiliary, or Assistant, Bishop came into the Church around the sixth century. Before that time, only one bishop served within an ecclesial province as sole spiritual leader of that region. Those clerics who hold this dignity are properly entitled “Titular Bishops” whom the Holy See has simultaneously assigned to assist a local Ordinary in the exercise of his episcopal responsibilities. The term ‘Auxiliary’ refers to the supporting role that the titular bishop provides a residential bishop but in every way, auxiliaries embody the fullness of the episcopal dignity. Although the Church considers both Linus and Cletus to be the first auxiliary bishops, as Assistants to St. Peter in the See of Rome, the first mention of the actual term “auxiliary bishop” was made in a decree by Pope Leo X (1513‐1521) entitled de Cardinalibus Lateranses (sess. IX). In this decree, Leo confirms the need for clerics who enjoy the fullness of Holy Orders to assist the Cardinal‐Bishops of the Suburbicarian Sees of Ostia, Velletri‐Segni, Sabina‐Poggia‐ Mirteto, Albano, Palestrina, Porto‐Santo Rufina, and Frascati, all of which surround the Roman Diocese. -

Hark the Heraldry Angels Sing

The UK Linguistics Olympiad 2018 Round 2 Problem 1 Hark the Heraldry Angels Sing Heraldry is the study of rank and heraldic arms, and there is a part which looks particularly at the way that coats-of-arms and shields are put together. The language for describing arms is known as blazon and derives many of its terms from French. The aim of blazon is to describe heraldic arms unambiguously and as concisely as possible. On the next page are some blazon descriptions that correspond to the shields (escutcheons) A-L. However, the descriptions and the shields are not in the same order. 1. Quarterly 1 & 4 checky vert and argent 2 & 3 argent three gouttes gules two one 2. Azure a bend sinister argent in dexter chief four roundels sable 3. Per pale azure and gules on a chevron sable four roses argent a chief or 4. Per fess checky or and sable and azure overall a roundel counterchanged a bordure gules 5. Per chevron azure and vert overall a lozenge counterchanged in sinister chief a rose or 6. Quarterly azure and gules overall an escutcheon checky sable and argent 7. Vert on a fess sable three lozenges argent 8. Gules three annulets or one two impaling sable on a fess indented azure a rose argent 9. Argent a bend embattled between two lozenges sable 10. Per bend or and argent in sinister chief a cross crosslet sable 11. Gules a cross argent between four cross crosslets or on a chief sable three roses argent 12. Or three chevrons gules impaling or a cross gules on a bordure sable gouttes or On your answer sheet: (a) Match up the escutcheons A-L with their blazon descriptions. -

Haminassa on Lippu Korkealla! Haminan Lippumaailma

HAMINASSA ON LIPPU KORKEALLA! HAMINAN LIPPUMAAILMA Haminan Lippumaailma on Haminan kaupungin hanke. Hami- nan Lippumaailman julkistaminen oli osa Suomi 100 -ohjelmaa, jolla Suomi juhli satavuotista itsenäisyyttään. Sisäministeriö, joka vastaa valtakunnallisista lippuun ja liputukseen liittyvistä toimista, on tukenut hanketta. Haminan Lippumaailma on liputukseen ja lippuhistoriaan keskittyvä puisto- ja näyttelykokonaisuus. Se pyrkii olemaan niin nähtävyys ja tärkeä matkailukohde kuin pedagoginen ja informatiivinen keskus. Lippumaailma avattiin 28.5.2018, jolloin julkistettiin myös ensimmäinen lippupuisto Lipputornin puistossa ja Suomen lipun tie -lippurivistö RUK:n puistossa. Samana päivänä juhlittiin Ha- mina Bastionissa 100-vuotiasta Suomen siniristilippua. Juhlassa kuultiin myös kantaesityksenä utsjokelaisten lasten laulama saamenkielinen Maamme-laulu. Suomen suurlippu meren rannalla juhlistaa Suomen itsenäi- syyden satavuotistaivalta. Sen lahjoittivat ulkovallat satavuo- tiaalle Suomelle ja Suomen kansalle. 100-metrinen suursalko sai pysyvän käyttöluvan joulukuussa 2019. Suurlippu ja lippupuistojen liput liehuvat erityisluvalla joka päivä ympäri vuoden valaistuna. Suurlipun lahjoittajamaiden liput liehuvat lisäksi kesäisin Haminan puistoissa erillisen suun- nitelman mukaan. Lippumaailma järjestää myös erilaisia näyt- telyitä liittyen lippuihin ja liputuskulttuuriin. 2 LIPPUMAAILMAN TAUSTAA MIKSI HAMINA? Haminan kaupunki on Suomen vanhin varuskuntakaupunki. Liputus ja liput kuuluvat keskeisesti sotilaskulttuuriin. Hami- nalla on jo parin -

The Colours of the Fleet

THE COLOURS OF THE FLEET TCOF BRITISH & BRITISH DERIVED ENSIGNS ~ THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE WORLDWIDE LIST OF ALL FLAGS AND ENSIGNS, PAST AND PRESENT, WHICH BEAR THE UNION FLAG IN THE CANTON “Build up the highway clear it of stones lift up an ensign over the peoples” Isaiah 62 vv 10 Created and compiled by Malcolm Farrow OBE President of the Flag Institute Edited and updated by David Prothero 15 January 2015 © 1 CONTENTS Chapter 1 Page 3 Introduction Page 5 Definition of an Ensign Page 6 The Development of Modern Ensigns Page 10 Union Flags, Flagstaffs and Crowns Page 13 A Brief Summary Page 13 Reference Sources Page 14 Chronology Page 17 Numerical Summary of Ensigns Chapter 2 British Ensigns and Related Flags in Current Use Page 18 White Ensigns Page 25 Blue Ensigns Page 37 Red Ensigns Page 42 Sky Blue Ensigns Page 43 Ensigns of Other Colours Page 45 Old Flags in Current Use Chapter 3 Special Ensigns of Yacht Clubs and Sailing Associations Page 48 Introduction Page 50 Current Page 62 Obsolete Chapter 4 Obsolete Ensigns and Related Flags Page 68 British Isles Page 81 Commonwealth and Empire Page 112 Unidentified Flags Page 112 Hypothetical Flags Chapter 5 Exclusions. Page 114 Flags similar to Ensigns and Unofficial Ensigns Chapter 6 Proclamations Page 121 A Proclamation Amending Proclamation dated 1st January 1801 declaring what Ensign or Colours shall be borne at sea by Merchant Ships. Page 122 Proclamation dated January 1, 1801 declaring what ensign or colours shall be borne at sea by merchant ships. 2 CHAPTER 1 Introduction The Colours of The Fleet 2013 attempts to fill a gap in the constitutional and historic records of the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth by seeking to list all British and British derived ensigns which have ever existed. -

140130 Selectboard Minutes.Pdf

1 Shutesbury Board of Selectmen Meeting Minutes January 30, 2014 Members present: Chairwoman Elaine Puleo and members Al Springer and April Stein. Members Absent: None. Remote participation: None. Staff present: Town Administrator Rebecca Torres, Administrative Secretary Leslie Bracebridge. Press present: None. Chairman Puleo opened the meeting at 6:30 P.M. at the Shutesbury Town Hall. Appointments Police Chief Harding: 1. February Staffing. 2. Chief Harding has talked with the Finance Committee and will also speak with Personnel Board members about using funds in his payroll line that he previously used to fund Quinn Bill obligations to fund educational incentives. Three considerations were brought up: One: What is written in the union contract. The union contract is up for review next year. Two: What precedence is set for the future. Three: If Shutesbury hires an officer eligible for Quinn benefits, the officer would receive the Quinn match because the town is still bound by the Quinn Bill even though the state match no longer exists. 3. In the presence of Chief Harding and Dog Officer Nancy Long Town Administrator Rebecca Torres briefed the Select Board on dog hearing procedures. 4. At 7:01 PM Chairman Puleo opened the dog hearing and administered the following oath: Do you solemnly state that the testimony that you give in the case now pending before this Board shall be the truth the whole truth and nothing but the truth?: James McNaughton – “yes”, Gail Huntress –“Yes”, Ronald Meck – “Yes”, Dog Officer Nancy Long “Yes”, and Chief Harding “Yes”. Elaine invited anyone to speak on current complaints. -

Colour Psychology Colour and Culture

74 COLOUR PSYCHOLOGY COLOUR AND CONTRAST 75 Colour Psychology Colour and Culture How people respond to colour is of great interest to those who work Research shows that ninety-eight languages have words for the same in marketing. Colour psychology research is often focused on how eleven basic colours;4 however, the meaning a colour may have can be the colour of a logo or a product will yield higher sales, and what very different. There are conflicting theories on whether the cultural colour preferences can be found in certain age groups and cultures. meanings of colours can be categorised. Meanings can change over The study of the psychological effects of colour have coincided time and depend on the context. Black may be the colour of mourning with colour theory in general. Goethe focused on the experience of in many countries, though a black book cover or a black poster is not colour in his Zur farbenlehre from 1810,1 in opposition to Sir Isaac always associated with death. Another example is that brides in China Newton’s rational approach. Goethe and Schiller coupled colours to traditionally wear red, but many brides have started to wear white in character traits: red for beautiful, yellow for good, green for useful, recent decades.4 The cultural meaning of colours is not set but always and blue for common. Gestalt psychology in the early 1900s also changing. The next few pages list some of the meanings of colours in attributed universal emotions to colours, a theory that was taught to different cultures. students at the Bauhaus by Wassily Kandinsky. -

FLAG of MONACO - a BRIEF HISTORY Where in the World

Part of the “History of National Flags” Series from Flagmakers FLAG OF MONACO - A BRIEF HISTORY Where In The World Trivia Apart from aspect ratio, the flag of Monaco is identical to the flag of Indonesia. Technical Specification Adopted: 1881 Proportion: 4:5 Design: A bi-colour in red and white, from top to bottom Colours: PMS: Red: 032 C CMYK: Red: 0% Cyan, 90% Magenta, 86% Yellow, 0% Black Brief History Monaco used to be a colony of the Italian city-state Genoa. A small isolated country between the mountains and the sea with one castle on the Rock of Monaco, overlooking the entire country. Francesco Grimaldi disguised himself and his men as Franciscan monks and infiltrated the castle to take control. It was not long before Genoan forces succeeded in ousting him. Later his descendents simply bought the castle and the realm from Genoa and turned it into a principality. At this point the flag of Genoa was the St. George’s flag. They allowed England, for a fee, to fly their flag so they could use their sea and ports to trade. The Monaco Coat of Arms has represented the country for as long as the Grimaldi dynasty has been in power, since the early 15th Century. Although the design has changed gradually over the years, the key elements have remained the same. The motto, 'Deo Juvante' is Latin for 'With God's Help'. This coat of arms today serves as the state flag. St George’s Flag of Genoa The Coat of Arms of Monaco The colours on the shield, red and white in a pattern known as 'lozengy argent and gules' in heraldic terms, are the national colours. -

Hamina Tattoo International Military Music Festival 30.7.-4.8.2018

Hamina Tattoo Magazine 1. painos / 1st edition Hamina Tattoo International BEST BANDS FROM AROUND Military Music Festival THE WORLD! 30.7.-4.8.2018 Puolustusvoimat 100 vuotta - juhlavuoden kunniaksi TANSSI VIEKÖÖN Avajaiskonsertti s. 6 SPIRIT OF HAMINA Yhteiskonsertti s. 7 TATTOO KLUBI s. 14 mm. Suvi Teräsniska JAZZ PALATSI s. 13 mm. Iiro Rantala International MilitaryHAMINA MTATTusicOO 2018 Festival 1 PUOLUSTUSVOIMAIN KOMENTAJA Hamina Tattoo 2018 suojelija kenraali Jarmo Lindberg Försvarsmaktens kommendör, Hamina Tattoo 2018 beskyddare, general Jarmo Lindbergs hälsning till Hamina Tattoo. Patron of Hamina Tattoo 2018 General Jarmo Lindberg Commander of the Finnish Defence Forces Hyvät sotilasmusiikin ystävät, Bästa vänner av militärmusik, Dear friends of military music! Puolustusvoimat täyttää tänä vuonna Försvarsmakten fyller i år 100 år. The Finnish Defence Forces reach the age 100 vuotta. Läpi historian Puolustusvoi- Genom sin historia har Försvarsmakten of 100 years in 2018. Throughout history, milla on ollut tärkeä tehtävä Suomen haft en viktig uppgift i att trygga Fin- the Defence Forces have played a key role itsenäisyyden ja kansalaisten elin- lands självständighet och medborgarnas in securing the independence of Finland mahdollisuuksien turvaamisessa sekä levnadsmöjligheter, såväl under freds- and the living conditions of Finns during rauhan että sotien aikana. som under krigstid. times of both peace and war. Juhlistamme merkkivuottamme yli Vårt jubileumsår firar vi med över We are celebrating the anniversary 120 tapahtumassa ympäri Suomea. 120 evenemang runt om i Finland. year in more than 120 events throughout Puolustusvoimia tehdään tunnetuksi Försvarsmakten görs känd på många Finland. The Defence Forces are present- monella tapaa, muun muassa sotilasmu- sätt, bland annat genom militärmusi- ed in a number of ways. -

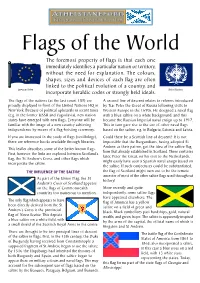

Flags of the World

ATHELSTANEFORD A SOME WELL KNOWN FLAGS Birthplace of Scotland’s Flag The name Japan means “The Land Canada, prior to 1965 used the of the Rising Sun” and this is British Red Ensign with the represented in the flag. The redness Canadian arms, though this was of the disc denotes passion and unpopular with the French sincerity and the whiteness Canadians. The country’s new flag represents honesty and purity. breaks all previous links. The maple leaf is the Another of the most famous flags Flags of the World traditional emblem of Canada, the white represents in the world is the flag of France, The foremost property of flags is that each one the vast snowy areas in the north, and the two red stripes which dates back to the represent the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. immediately identifies a particular nation or territory, revolution of 1789. The tricolour, The flag of the United States of America, the ‘Stars and comprising three vertical stripes, without the need for explanation. The colours, Stripes’, is one of the most recognisable flags is said to represent liberty, shapes, sizes and devices of each flag are often in the world. It was first adopted in 1777 equality and fraternity - the basis of the republican ideal. linked to the political evolution of a country, and during the War of Independence. The flag of Germany, as with many European Union United Nations The stars on the blue canton incorporate heraldic codes or strongly held ideals. European flags, is based on three represent the 50 states, and the horizontal stripes. -

Flags and Banners

Flags and Banners A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton Contents 1 Flag 1 1.1 History ................................................. 2 1.2 National flags ............................................. 4 1.2.1 Civil flags ........................................... 8 1.2.2 War flags ........................................... 8 1.2.3 International flags ....................................... 8 1.3 At sea ................................................. 8 1.4 Shapes and designs .......................................... 9 1.4.1 Vertical flags ......................................... 12 1.5 Religious flags ............................................. 13 1.6 Linguistic flags ............................................. 13 1.7 In sports ................................................ 16 1.8 Diplomatic flags ............................................ 18 1.9 In politics ............................................... 18 1.10 Vehicle flags .............................................. 18 1.11 Swimming flags ............................................ 19 1.12 Railway flags .............................................. 20 1.13 Flagpoles ............................................... 21 1.13.1 Record heights ........................................ 21 1.13.2 Design ............................................. 21 1.14 Hoisting the flag ............................................ 21 1.15 Flags and communication ....................................... 21 1.16 Flapping ................................................ 23 1.17 See also ...............................................