Download Program Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

029I-HMVCX1924XXX-0000A0.Pdf

This Catalogue contains all Double-Sided Celebrity Records issued up to and including March 31st, 1924. The Single-Sided Celebrity Records are also included, and will be found under the records of the following artists :-CLARA Burr (all records), CARUSO and MELBA (Duet 054129), CARUSO,TETRAZZINI, AMATO, JOURNET, BADA, JACOBY (Sextet 2-054034), KUBELIK, one record only (3-7966), and TETRAZZINI, one record only (2-033027). International Celebrity Artists ALDA CORSI, A. P. GALLI-CURCI KURZ RUMFORD AMATO CORTOT GALVANY LUNN SAMMARCO ANSSEAU CULP GARRISON MARSH SCHIPA BAKLANOFF DALMORES GIGLI MARTINELLI SCHUMANN-HEINK BARTOLOMASI DE GOGORZA GILLY MCCORMACK Scorn BATTISTINI DE LUCA GLUCK MELBA SEMBRICH BONINSEGNA DE' MURO HEIFETZ MOSCISCA SMIRN6FF BORI DESTINN HEMPEL PADEREWSKI TAMAGNO BRASLAU DRAGONI HISLOP PAOLI TETRAZZINI BI1TT EAMES HOMER PARETO THIBAUD CALVE EDVINA HUGUET PATTt WERRENRATH CARUSO ELMAN JADLOWKER PLANCON WHITEHILL CASAZZA FARRAR JERITZA POLI-RANDACIO WILLIAMS CHALIAPINE FLETA JOHNSON POWELL ZANELLIi CHEMET FLONZALEY JOURNET RACHM.4NINOFF ZIMBALIST CICADA QUARTET KNIIPFER REIMERSROSINGRUFFO CLEMENT FRANZ KREISLER CORSI, E. GADSKI KUBELIK PRICES DOUBLE-SIDED RECORDS. LabelRed Price6!-867'-10-11.,613,616/- (D.A.) 10-inch - - Red (D.B.) 12-inch - - Buff (D.J.) 10-inch - - Buff (D.K.) 12-inch - - Pale Green (D.M.) 12-inch Pale Blue (D.O.) 12-inch White (D.Q.) 12-inch - SINGLE-SIDED RECORDS included in this Catalogue. Red Label 10-inch - - 5'676 12-inch - - Pale Green 12-inch - 10612,615j'- Dark Blue (C. Butt) 12-inch White (Sextet) 12-inch - ALDA, FRANCES, Soprano (Ahl'-dah) New Zealand. She Madame Frances Aida was born at Christchurch, was trained under Opera Comique Paris, Since Marcltesi, and made her debut at the in 1904. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

Il Trovatore Was Made Stage Director Possible by a Generous Gift from Paula Williams the Annenberg Foundation

ilGIUSEPPE VERDItrovatore conductor Opera in four parts Marco Armiliato Libretto by Salvadore Cammarano and production Sir David McVicar Leone Emanuele Bardare, based on the play El Trovador by Antonio García Gutierrez set designer Charles Edwards Tuesday, September 29, 2015 costume designer 7:30–10:15 PM Brigitte Reiffenstuel lighting designed by Jennifer Tipton choreographer Leah Hausman The production of Il Trovatore was made stage director possible by a generous gift from Paula Williams The Annenberg Foundation The revival of this production is made possible by a gift of the Estate of Francine Berry general manager Peter Gelb music director James Levine A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, and the San Francisco principal conductor Fabio Luisi Opera Association 2015–16 SEASON The 639th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S il trovatore conductor Marco Armiliato in order of vocal appearance ferr ando Štefan Kocán ines Maria Zifchak leonor a Anna Netrebko count di luna Dmitri Hvorostovsky manrico Yonghoon Lee a zucena Dolora Zajick a gypsy This performance Edward Albert is being broadcast live on Metropolitan a messenger Opera Radio on David Lowe SiriusXM channel 74 and streamed at ruiz metopera.org. Raúl Melo Tuesday, September 29, 2015, 7:30–10:15PM KEN HOWARD/METROPOLITAN OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Verdi’s Il Trovatore Musical Preparation Yelena Kurdina, J. David Jackson, Liora Maurer, Jonathan C. Kelly, and Bryan Wagorn Assistant Stage Director Daniel Rigazzi Italian Coach Loretta Di Franco Prompter Yelena Kurdina Assistant to the Costume Designer Anna Watkins Fight Director Thomas Schall Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted by Cardiff Theatrical Services and Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Lyric Opera of Chicago Costume Shop and Metropolitan Opera Costume Department Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department Ms. -

Il Trovatore

Synopsis Act I: The Duel Count di Luna is obsessed with Leonora, a young noblewoman in the queen’s service, who does not return his love. Outside the royal residence, his soldiers keep watch at night. They have heard an unknown troubadour serenading Leonora, and the jealous count is determined to capture and punish him. To keep his troops awake, the captain, Ferrando, recounts the terrible story of a gypsy woman who was burned at the stake years ago for bewitching the count’s infant brother. The gypsy’s daughter then took revenge by kidnapping the boy and throwing him into the flames where her mother had died. The charred skeleton of a baby was discovered there, and di Luna’s father died of grief soon after. The gypsy’s daughter disappeared without a trace, but di Luna has sworn to find her. In the palace gardens, Leonora confides in her companion Ines that she is in love with a mysterious man she met before the outbreak of the war and that he is the troubadour who serenades her each night. After they have left, Count di Luna appears, looking for Leonora. When she hears the troubadour’s song in the darkness, Leonora rushes out to greet her beloved but mistakenly embraces di Luna. The troubadour reveals his true identity: He is Manrico, leader of the partisan rebel forces. Furious, the count challenges him to fight to the death. Act II: The Gypsy During the duel, Manrico overpowered the count, but some instinct stopped him from killing his rival. The war has raged on. -

Knoxville: Summer of 1915” Danielle E

Undergraduate Research Journal Volume 19 Article 12 2015 Musical and Cultural Significance in Samuel Barber’s “Knoxville: Summer of 1915” Danielle E. Kluver University of Nebraska at Kearney Follow this and additional works at: https://openspaces.unk.edu/undergraduate-research-journal Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Kluver, Danielle E. (2015) "Musical and Cultural Significance in Samuel Barber’s “Knoxville: Summer of 1915”," Undergraduate Research Journal: Vol. 19 , Article 12. Available at: https://openspaces.unk.edu/undergraduate-research-journal/vol19/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of Undergraduate Research & Creative Activity at OpenSPACES@UNK: Scholarship, Preservation, and Creative Endeavors. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Research Journal by an authorized editor of OpenSPACES@UNK: Scholarship, Preservation, and Creative Endeavors. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Musical and Cultural Significance in Samuel Barber’s “Knoxville: Summer of 1915” Danielle E. Kluver INTRODUCTION “We are talking now of summer evenings in Knoxville, Tennessee in the time that I lived there so successfully disguised to myself as a child” (Agee 3). These first words of James Agee’s prose poem “Knoxville: Summer of 1915,” introduce the reader to a world of his youth – rural Tennessee in the early part of the century. Agee’s highly descriptive and lyrical language in phrases such as “these sweet pale streamings in the light out their pallors,” (Agee 5) invites the reader to use all his senses and become enveloped in the inherent music of the language. Is it any wonder that upon reading Agee’s words, composer Samuel Barber should be drawn into this narrative that enlivens the senses and touches the heart with its complexity of human emotions told through the recollections of childhood from a time of youth and innocence. -

Toscanini IV – La Scala and the Metropolitan Opera

Toscanini IV – La Scala and the Metropolitan Opera Trying to find a balance between what the verbal descriptions of Toscanini’s conducting during the period of roughly 1895-1915 say of him and what he actually did can be like trying to capture lightning in a bottle. Since he made no recordings before December 1920, and instrumental recordings at that, we cannot say with any real certainty what his conducting style was like during those years. We do know, from the complaints of Tito Ricordi, some of which reached Giuseppe Verdi’s ears, that Italian audiences hated much of what Toscanini was doing: conducting operas at the written tempos, not allowing most unwritten high notes (but not all, at least not then), refusing to encore well-loved arias and ensembles, and insisting in silence as long as the music was being played and sung. In short, he instituted the kind of audience decorum we come to expect today, although of course even now (particularly in Italy and America, not so much in England) we still have audiences interrupting the flow of an opera to inject their bravos and bravas when they should just let well enough alone. Ricordi complained to Verdi that Toscanini was ruining his operas, which led Verdi to ask Arrigo Boïto, whom he trusted, for an assessment. Boïto, as a friend and champion of the conductor, told Verdi that he was simply conducting the operas pretty much as he wrote them and not allowing excess high notes, repeats or breaks in the action. Verdi was pleased to hear this; it is well known that he detested slowly-paced performances of his operas and, worse yet, the interpolated high notes he did not write. -

110308-10 Bk Lohengrineu 13/01/2005 03:29Pm Page 12

110308-10 bk LohengrinEU 13/01/2005 03:29pm Page 12 her in his arms, reproaching her for bringing their @ Ortrud comes forward, declaring the swan to be happiness to an end. She begs him to stay, to witness her Elsa’s brother, the heir to Brabant, whom she had repentance, but he is adamant. The men urge him to bewitched with the help of her own pagan gods. WAGNER stay, to lead them into battle, but in vain. He promises, Lohengrin kneels in prayer, and when the white dove of however, that Germany will be victorious, never to be the Holy Grail appears, he unties the swan. As it sinks defeated by the hordes from the East. Shouts announce down, Gottfried emerges. Ortrud sinks down, with a the appearance of the swan. cry, while Gottfried bows to the king and greets Elsa. Lohengrin Lohengrin leaps quickly into the boat, which is drawn ! Lohengrin greets the swan. Sorrowfully he turns away by the white dove. Elsa sees him, as he makes his towards it, telling Elsa that her brother is still alive, and sad departure. She faints into her brother’s arms, as the G WIN would have returned to her a year later. He leaves his knight disappears, sailing away into the distance. AN DG horn, sword, and ring for Gottfried, kisses Elsa, and G A F SS moves towards the boat. L E Keith Anderson O N W Mark Obert-Thorn Mark Obert-Thorn is one of the world’s most respected transfer artist/engineers. He has worked for a number of specialist labels, including Pearl, Biddulph, Romophone and Music & Arts. -

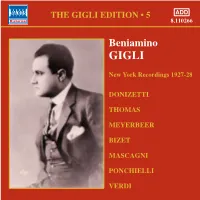

110266 Bk Gigli5 EU 19/05/2004 01:53Pm Page 5

110266 bk Gigli5 EU 19/05/2004 01:53pm Page 5 BIZET: Les pêcheurs de perles: 6 Tu che a Dio spiegasti l’ali (Act 3) 4:27 VERDI: Rigoletto: THOMAS: Mignon: ADD 1 Del tempio al limitar (Act 1) 4:27 Ezio Pinza, bass; Metropolitan Opera Chorus ! Bella figlia dell’amore (Act 3) 4:12 % Ah, non credevi tu (Act 3) 4:04 THE GIGLI EDITION • 5 Giuseppe De Luca, baritone Recorded 12th December 1927 Amelita Galli-Curci, soprano; Recorded 30th November 1928 8.110266 Recorded 28th November 1927 in Liederkranz Hall, New York Louise Homer, contralto; at 16 West 64th Street, New York in Liederkranz Hall, New York Matrix: CVE-41226-1 Giuseppe De Luca, baritone Matrix: CVE-45121-3 Matrix: CVE-41071-2 First issued on Victor 8096 Recorded 16th December 1927 First issued on Victor 6905 First issued on Victor 8084 in Liederkranz Hall, New York 7 Tombe degl’avi miei (Act 3) 4:46 Matrix: CVE-41233-1 ^ Addio, Mignon, fa core (Act 2) 3:07 PONCHIELLI: La Gioconda: Recorded 12th December 1927 First issued on Victor 10012 Recorded 30th November 1928 Beniamino 2 Enzo Grimaldo, Principe di Santafior! 4:30 in Liederkranz Hall, New York at 16 West 64th Street, New York (Act 1) Matrix: CVE-41227-2 VERDI: Rigoletto Matrix: CVE-45119-4 Giuseppe De Luca, baritone Unpublished on 78 rpm @ Bella figlia dell’amore (Act 3) 4:26 First issued on Victor 6905 GIGLI Recorded 28th November 1927 8 Giusto cielo, rispondete (Act 3) 3:54 Amelita Galli-Curci, soprano; in Liederkranz Hall, New York Ezio Pinza, bass; Metropolitan Opera Chorus Louise Homer, contralto; MEYERBEER: L’africaine: -

Enrico Caruso

NI 7924/25 Also Available on Prima Voce ENRICO CARUSO Opera Volume 3 NI 7803 Caruso in Opera Volume One NI 7866 Caruso in Opera Volume Two NI 7834 Caruso in Ensemble NI 7900 Caruso – The Early Years : Recordings from 1902-1909 NI 7809 Caruso in Song Volume One NI 7884 Caruso in Song Volume Two NI 7926/7 Caruso in Song Volume Three 12 NI 7924/25 NI 7924/25 Enrico Caruso 1873 - 1921 • Opera Volume 3 and pitch alters (typically it rises) by as much as a semitone during the performance if played at a single speed. The total effect of adjusting for all these variables is revealing: it questions the accepted wisdom that Caruso’s voice at the time of his DISC ONE early recordings was very much lighter than subsequently. Certainly the older and 1 CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA, Mascagni - O Lola ch’ai di latti la cammisa 2.50 more artistically assured he became, the tone became even more massive, and Rec: 28 December 1910 Matrix: B-9745-1 Victor Cat: 87072 likewise the high A naturals and high B flats also became even more monumental in Francis J. Lapitino, harp their intensity. But it now appears, from this evidence, that the baritone timbre was 2 LA GIOCONDA, Ponchielli - Cielo e mar 2.57 always present. That it has been missed is simply the result of playing the early discs Rec: 14 March 1910 Matrix: C-8718-1 Victor Cat: 88246 at speeds that are consistently too fast. 3 CARMEN, Bizet - La fleur que tu m’avais jetée (sung in Italian) 3.53 Rec: 7 November 1909 Matrix: C-8349-1 Victor Cat: 88209 Of Caruso’s own opinion on singing and the effort required we know from a 4 STABAT MATER, Rossini - Cujus animam 4.47 published interview that he believed it should be every singers aim to ensure ‘that in Rec: 15 December 1913 Matrix: C-14200-1 Victor Cat: 88460 spite of the creation of a tone that possesses dramatic tension, any effort should be directed in 5 PETITE MESSE SOLENNELLE, Rossini - Crucifixus 3.18 making the actual sound seem effortless’. -

10-06-2018 Aida Mat.Indd

Synopsis Act I Egypt, during the reign of the pharaohs. At the royal palace in Memphis, the high priest Ramfis tells the warrior Radamès that Ethiopia is preparing another attack against Egypt. Radamès hopes to command the Egyptian army. He is in love with Aida, the Ethiopian slave of Princess Amneris, the king’s daughter, and he believes that victory in the war would enable him to free and marry her. But Amneris also loves Radamès and is jealous of Aida, whom she suspects of being her rival for Radamès’s affection. A messenger brings news that the Ethiopians are advancing. The king names Radamès to lead the army, and all prepare for war. Left alone, Aida is torn between her love for Radamès and loyalty to her native country, where her father, Amonasro, is king. In the temple of Vulcan, the priests consecrate Radamès to the service of the god Ptah. Ramfis orders Radamès to protect the homeland. Act II Ethiopia has been defeated, and in her chambers, Amneris waits for the triumphant return of Radamès. Alone with Aida, she pretends that Radamès has fallen in battle, then says that he is still alive. Aida’s reactions leave no doubt that she loves Radamès. Amneris is certain that she will defeat her rival. At the city gates, the king and Amneris observe the victory celebrations and praise Radamès’s triumph. Soldiers lead in the captured Ethiopians, among them Amonasro, who signals his daughter not to reveal his identity as king. Amonasro’s eloquent plea for mercy impresses Radamès, and the warrior asks that the order for the prisoners to be executed be overruled and that they be freed instead. -

Daniel Freiberg's Latin American Chronicles Frank Proto's Paganini in Metropolis

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2019 An Exploration of Two Twenty-First Century American Works for Clarinet and Orchestra: Daniel Freiberg's Latin American Chronicles Frank Proto's PKaatsugyaa Ynuaisani in Metropolis Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC AN EXPLORATION OF TWO TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY AMERICAN WORKS FOR CLARINET AND ORCHESTRA: DANIEL FREIBERG’S LATIN AMERICAN CHRONICLES FRANK PROTO’S PAGANINI IN METROPOLIS By KATSUYA YUASA A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music 2019 Katsuya Yuasa defended this treatise on April 5, 2019. The members of the supervisory committee were: Deborah Bish Professor Co-Directing Treatise Jonathan Holden Professor Co-Directing Treatise Richard Clary University Representative Eva Amsler Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am indebted to several people for their support while finishing my studies. First and foremost, I would like to thank my graduate committee for their guidance and constructive feedback during my final semesters at Florida State University. I would like to give my utmost gratitude to my professors Deborah Bish and Jonathan Holden for helping me become the musician and person I am today. Thank you for your patience and kindness throughout my apprenticeship. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ..................................................................................................................................v Abstract ......................................................................................................................................... -

Der Rosenkavalier

110277-79 bk Rosenkav 21/10/2003 3:10 pm Page 1 ADD Great Opera Performances 8.110277-79 Richard 3 CDs STRAUSS Der Rosenkavalier Risë Stevens • Eleanor Steber • Erna Berger • Emanuel List Chorus and Orchestra of the Metropolitan Opera, New York • Fritz Reiner American Broadcasting Corporation Telecast 21st November 1949 110277-79 bk Rosenkav 21/10/2003 3:10 pm Page 2 Great Opera Performance Richard STRAUSS (1864-1949) Der Rosenkavalier Telecast 21st November 1949 opening night of the 1949/1950 Metropolitan Opera season Octavian . Risë Stevens Die Feldmarschallin . Eleanor Steber Baron Ochs . Emanuel List Sophie . Erna Berger Faninal . Hugh Thompson Annina . Martha Lipton Valzacchi . Peter Klein Italian Singer . Giuseppe Di Stefano Marianne Leitmetzerin . Thelma Votipka Mahomet . Peggy Smithers Marschallin’s Major-domo . Emery Darcy Orphans . Paula Lenchner, Maxine Stellman, Thelma Altman Milliner . Lois Hunt Animal Vendor . Leslie Chabay Hairdresser . Matthew Vittucci Notary . Gerhard Pechner Leopold . Ludwig Burgstaller Faninal’s Major-domo . Paul Franke Innkeeper . Leslie Chabay Police Commissioner . Lorenzo Alvary Chorus and Orchestra of the Metropolitan Opera House Fritz Reiner conducting 8.110277-79 2 110277-79 bk Rosenkav 21/10/2003 3:10 pm Page 15 Producer’s note During the late 1940s, commercial television became a viable reality and the possibilities for this new medium were almost limitless. On 29th November 1948, The Metropolitan Opera Company’s first live telecast took place. The occasion was the opening night of the 1948-49 season, and the opera was Verdi’s Otello. Incidentally, this performance was only available to television viewers and was not broadcast via radio. The following year, the Metropolitan’s opening night performance of Richard Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier was similarly telecast.