Il Trovatore Was Made Stage Director Possible by a Generous Gift from Paula Williams the Annenberg Foundation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8.112023-24 Bk Menotti Amelia EU 26-03-2010 9:41 Pagina 16

8.112023-24 bk Menotti Amelia_EU 26-03-2010 9:41 Pagina 16 Gian Carlo MENOTTI Also available The Consul • Amelia al ballo LO M CAR EN N OT IA T G I 8.669019 19 gs 50 din - 1954 Recor Patricia Neway • Marie Powers • Cornell MacNeil 8.669140-41 Orchestra • Lehman Engel Margherita Carosio • Rolando Panerai • Giacinto Prandelli Chorus and Orchestra of La Scala, Milan • Nino Sanzogno 8.112023-24 16 8.112023-24 bk Menotti Amelia_EU 26-03-2010 9:41 Pagina 2 MENOTTI CENTENARY EDITION Producer’s Note This CD set is the first in a series devoted to the compositions, operatic and otherwise, of Gian Carlo Menotti on Gian Carlo the occasion of his centenary in 2011. The recordings in this series date from the mid-1940s through the late 1950s, and will feature several which have never before appeared on CD, as well as some that have not been available in MENOTTI any form in nearly half a century. The present recording of The Consul, which makes its CD début here, was made a month after the work’s (1911– 2007) Philadelphia première. American Decca was at the time primarily a “pop” label, the home of Bing Crosby and Judy Garland, and did not yet have much experience in the area of Classical music. Indeed, this recording seems to have been done more because of the work’s critical acclaim on the Broadway stage than as an opera, since Decca had The Consul also recorded Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman with members of the original cast around the same time. -

CHAN 3036 BOOK COVER.Qxd 22/8/07 2:50 Pm Page 1

CHAN 3036 BOOK COVER.qxd 22/8/07 2:50 pm Page 1 CHAN 3036(2) CHANDOS O PERA I N ENGLISH Il Trovatore David Parry PETE MOOES FOUNDATION CHAN 3036 BOOK.qxd 22/8/07 3:15 pm Page 2 Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901) Il trovatore (The Troubadour) Opera in four parts AKG Text by Salvatore Cammarano, from the drama El trovador by Antonio Garcia Gutiérrez English translation by Tom Hammond Count di Luna, a young nobleman of Aragon ....................................................................Alan Opie baritone Ferrando, captain of the Count’s guard ..................................................................................Clive Bayley bass Doña Leonora, lady-in-waiting to the Princess of Aragon ..............................................Sharon Sweet soprano Inez, confidante of Leonora ........................................................................................Helen Williams soprano Azucena, a gipsy woman from Biscay ....................................................................Anne Mason mezzo-soprano Manrico (The Troubadour), supposed son of Azucena, a rebel under Prince Urgel ........Dennis O’Neill tenor Ruiz, a soldier in Manrico’s service ..................................................................................Marc Le Brocq tenor A Gipsy, a Messenger, Servants and Retainers of the Count, Followers of Manrico, Soldiers, Gipsies, Nuns, Guards Geoffrey Mitchell Choir London Philharmonic Orchestra Nicholas Kok and Gareth Hancock assistant conductors David Parry Further appearances in Opera in English Dennis O’Neill: -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

MICHAEL FINNISSY at 70 the PIANO MUSIC (9) IAN PACE – Piano Recital at Deptford Town Hall, Goldsmith’S College, London

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2016). Michael Finnissy at 70: The piano music (9). This is the other version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17520/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] MICHAEL FINNISSY AT 70 THE PIANO MUSIC (9) IAN PACE – Piano Recital at Deptford Town Hall, Goldsmith’s College, London Thursday December 1st, 2016, 6:00 pm The event will begin with a discussion between Michael Finnissy and Ian Pace on the Verdi Transcriptions. MICHAEL FINNISSY Verdi Transcriptions Books 1-4 (1972-2005) 6:15 pm Books 1 and 2: Book 1 I. Aria: ‘Sciagurata! a questo lido ricercai l’amante infido!’, Oberto (Act 2) II. Trio: ‘Bella speranza in vero’, Un giorno di regno (Act 1) III. Chorus: ‘Il maledetto non ha fratelli’, Nabucco (Part 2) IV. -

La Donna Del Lago , the Met's First Production of the Bel Canto Showcase, on Great Performances at the Met

Press Contacts: Harry Forbes, WNET 212-560-8027 or [email protected] Eva Chien 212-870-4589 or [email protected] Press materials: http://pressroom.pbs.org or http://www.thirteen.org/13pressroom Website: http://www.pbs.org/wnet/gperf Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/GreatPerformances Twitter: @GPerfPBS Joyce DiDonato and Juan Diego Flórez Star In Rossini's La Donna del Lago , the Met's First Production of the Bel Canto Showcase, on Great Performances at the Met Sunday, August 2 at 12 p.m. on PBS Joyce DiDonato and Juan Diego Flórez headline Rossini's bel canto tour-de-force La Donna del Lago on THIRTEEN’S Great Performances at the Met Sunday, August 2 at 12 p.m. on PBS. (Check local listings.) In this Rossini classic based on the work by Sir Walter Scott, DiDonato sings the title role of Elena, the lady of the lake pursued by two men, with Flórez in the role of Giacomo, the benevolent king of Scotland. Michele Mariotti , last featured in the Great Performance at the Met broadcast of Rigoletto , conducts debuting Scottish director Paul Curran's staging, a co-production with Santa Fe Opera. The cast also includes Daniela Barcellona in the trouser role of Malcolm, John Osborn as Rodrigo, and Oren Gradus as Duglas. "The wondrous Ms. DiDonato and Mr. Mariotti, the fast-rising young Italian conductor, seemed almost in competition to see who could make music with more delicacy,” noted The New York Times earlier this year, and “Mr. Mariotti drew hushed gentle and transparent playing from the inspired Met orchestra.” And NY Classical Review raved, "Joyce DiDonato…was beyond perfect.. -

Web Site Leads to GOP Complaint

Johnny Appleseed Linden students celebrated the American legend of Johnny Appleseed last week. Serving Linden, Roselle, Rahway and Elizabeth Page 3 LINDEN, N.J WWW.LOCALSOURCE.COM 75 CENTS VOL. 89 NO. 39 THURSDAY OCTOBER 5, 2006 Web site leads to GOP complaint By Kitty Wilder paid a total of $9 for two domain Kennedy said he was not aware ofthe site, Enforcement Commission said it is Managing Editor CAMPAIGN UPDATE names. The second domain name was adding, “It’s nothing I’m supporting.” not the commission’s policy to con RAHWAY — Local Republicans used to create a second Rahway He said Devine is not a consultant firm or deny complaints filed. have filed a complaint with the state Republicans for Kennedy Web site at for his campaign, but he is paid for Web sites have become common in alleging a Democratic campaign Lund. It did not contain a disclaimer. www.timeforchange2006.net. printing services. campaigning and are treated like other worker created a Web site intended to The site, which did not include a The address is similar to another Devine said he is a consultant for campaign literature, Davis said. They misrepresent their party. disclaimer, contained a similar address Bodine for Mayor address, www.time- Kennedy, adding, “I advise the Demo are required to include a disclaimer The complaint, filed Friday with to the homepage for the campaign rep forchange2006.com. cratic Party on strategic and tactical clarifying who paid for the site. the state Election Law Enforcement resenting the council candidates and Cassio said the similarity between measures to promote their candidates The commission follows a standard Commission, alleges the group Rah mayoral candidate Larry Bodine. -

Verdi, Moffo, Bergonzi, Verrett, Macneil, Tozzi

Verdi Luisa Miller mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Luisa Miller Country: Italy Released: 1965 Style: Opera MP3 version RAR size: 1127 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1383 mb WMA version RAR size: 1667 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 183 Other Formats: WMA DXD DTS MP2 MMF ASF AU Tracklist A1 Overture A2 Act I (Part I) B Act I (Concluded) C Act II (Part I) D Act II (Concluded) E Act III (Part I) F Act III (Concluded) Credits Baritone Vocals [Miller] – Cornell MacNeil Bass Vocals [Count Walter] – Giorgio Tozzi Bass Vocals [Wurm] – Ezio Flagello Chorus – RCA Italiana Opera Chorus Chorus Master – Nino Antonellini Chorus Master [Assistant] – Giuseppe Piccillo Composed By – Verdi* Conductor – Fausto Cleva Conductor [Assistant] – Fernando Cavaniglia, Luigi Ricci Engineer – Anthony Salvatore Libretto By – Salvatore Cammarano Libretto By [Translation] – William Weaver* Liner Notes – Francis Robinson Mezzo-soprano Vocals [Federica] – Shirley Verrett Mezzo-soprano Vocals [Laura] – Gabriella Carturan Orchestra – RCA Italiana Opera Orchestra Producer – Richard Mohr Soprano Vocals [Luisa] – Anna Moffo Sound Designer [Stereophonic Stage Manager] – Peter F. Bonelli Tenor Vocals [A Peasant] – Piero De Palma Tenor Vocals [Rodolfo] – Carlo Bergonzi Notes Issued with 40-page booklet containing credits, liner notes, photographs and libretto in Italian with English translation Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Verdi*, Moffo*, Verdi*, Moffo*, Bergonzi*, Verrett*, Bergonzi*, MacNeil*, Tozzi*, Verrett*, -

Andrea Chénier Giordano

ANDREA CHÉNIER GIORDANO Argument MT / 3 Andrea Chénier Argument 4 / 5 Andrea Chénier Andrea Chénier torna al Liceu amb la producció de David McVicar. (ROH/Bill Cooper) Fitxa L’autèntic 6 / 7 9 45 André Chénier Alain Verjat Repartiment 10 Entrevista a 53 Sondra Radvanovsky Amb el teló abaixat 12 Andrea Chénier al 61 Gran Teatre del Liceu 17 Argument Jaume Tribó Cronologia 27 English Synopsis 68 Jordi Fernández M. Selecció d’enregistraments Andrea Chénier, Javier Pérez-Senz 35 una òpera verista 77 entre el Romanticisme i el romàntic Biografies Jesús Ruiz Mantilla 80 Andrea Chénier Temporada 2017-18 8 / 9 ANDREA CHÉNIER Dramma storico en quatre actes. Llibret de Luigi Illica. Música d’Umberto Giordano. Estrenes 28 de març de 1896: estrena absoluta al Teatro alla Scala de Milà 12 de novembre de 1898: estrena a Barcelona al Gran Teatre del Liceu 17 d’octubre de 2007: última representació al Liceu Total de representacions al Liceu: 49 Març 2018 Torn Tarifa 9 20:00 1 Durada total aproximada 2h 35m 10 20:00 PB 6 (*): Amb audiodescripció 12 20:00 1 13 20:00 PC 6 15 20:00 1 17 20:00 C 4 18 17:00 T 3 19 20:00 G 5 21 20:00 D 3 22 20:00 B 4 24 20:00 E 2 25 18:00 F 3 27 20:00 A 4 28* 20:00 H 4 Uneix-te a la conversa #AndreaChénierLiceu liceubarcelona.cat facebook.com/liceu @liceu_cat @liceu_opera_barcelona Andrea Chénier Andrea Chénier, poeta Madelon, anciana revolucionària Jonas Kaufmann 9, 12 i 15 de març Anna Tomowa-Sintow Jorge de León 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, 24 i 27 de març 10, 13, 17, 19, 22, 25 i 28 de març Elena Zaremba Antonello Palombi 18, 21, -

Ernani Program

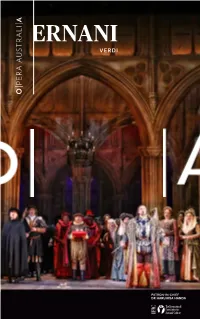

VERDI PATRON-IN-CHIEF DR HARUHISA HANDA Celebrating the return of World Class Opera HSBC, as proud partner of Opera Australia, supports the many returns of 2021. Together we thrive Issued by HSBC Bank Australia Limited ABN 48 006 434 162 AFSL No. 232595. Ernani Composer Ernani State Theatre, Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) Diego Torre Arts Centre Melbourne Librettist Don Carlo, King of Spain Performance dates Francesco Maria Piave Vladimir Stoyanov 13, 15, 18, 22 May 2021 (1810-1876) Don Ruy Gomez de Silva Alexander Vinogradov Running time: approximately 2 hours and 30 Conductor Elvira minutes, including one interval. Carlo Montanaro Natalie Aroyan Director Giovanna Co-production by Teatro alla Scala Sven-Eric Bechtolf Jennifer Black and Opera Australia Rehearsal Director Don Riccardo Liesel Badorrek Simon Kim Scenic Designer Jago Thank you to our Donors Julian Crouch Luke Gabbedy Natalie Aroyan is supported by Costume Designer Roy and Gay Woodward Kevin Pollard Opera Australia Chorus Lighting Designer Chorus Master Diego Torre is supported by Marco Filibeck Paul Fitzsimon Christine Yip and Paul Brady Video Designer Assistant Chorus Master Paul Fitzsimon is supported by Filippo Marta Michael Curtain Ina Bornkessel-Schlesewsky and Matthias Schlesewsky Opera Australia Actors The costumes for the role of Ernani in this production have been Orchestra Victoria supported by the Concertmaster Mostyn Family Foundation Sulki Yu You are welcome to take photos of yourself in the theatre at interval, but you may not photograph, film or record the performance. -

ARSC Journal

TOSCANINI LIVE BEETHOVEN: Missa Solemnis in D, Op. 123. Zinka Milanov, soprano; Bruna Castagna, mezzo-soprano; Jussi Bjoerling, tenor; Alexander Kipnis, bass; Westminster Choir; VERDI: Missa da Requiem. Zinka Milanov, soprano; Bruna Castagna, mezzo-soprano; Jussi Bjoerling, tenor; Nicola Moscona, bass; Westminster Choir, NBC Symphony Orchestra, Arturo Toscanini, cond. Melodram MEL 006 (3). (Three Discs). (Mono). BEETHOVEN: Symphony No. 9 in D Minor, Op. 125. Vina Bovy, soprano; Kerstin Thorborg, contralto; Jan Peerce, tenor; Ezio Pinza, bass; Schola Cantorum; Arturo Toscanini Recordings Association ATRA 3007. (Mono). (Distributed by Discocorp). BRAHMS: Symphonies: No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68; No. 2 in D, Op. 73; No. 3 in F, Op. 90; No. 4 in E Minor, Op. 98; Tragic Overture, Op. 81; Variations on a Theme by Haydn, Op. 56A. Philharmonia Orchestra. Cetra Documents. Documents DOC 52. (Four Discs). (Mono). BRAHMS: Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68; Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, No. 2 in B Flat, Op. 83. Serenade No. 1 in D, Op. 11: First movement only; Vladimir Horowitz, piano (in the Concerto); Melodram MEL 229 (Two Discs). BRAHMS: Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68. MOZART: Symphony No. 40 in G Minor, K. 550. TCHAIKOVSKY: Romeo and Juliet (Overture-Fantasy). WAGNER: Lohengrin Prelude to Act I. WEBER: Euryanthe Overture. Giuseppe Di Stefano Presenta GDS 5001 (Two Discs). (Mono). MOZART: Symphony No. 35 in D, K. 385 ("Haffner") Rehearsal. Relief 831 (Mono). TOSCANINI IN CONCERT: Dell 'Arte DA 9016 (Mono). Bizet: Carmen Suite. Catalani: La Wally: Prelude; Lorelei: Dance of the Water ~· H~rold: Zampa Overture. -

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company Sally Elizabeth Drew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council September 2018 1 2 Abstract This thesis examines the working culture of the Decca Record Company, and how group interaction and individual agency have made an impact on the production of music recordings. Founded in London in 1929, Decca built a global reputation as a pioneer of sound recording with access to the world’s leading musicians. With its roots in manufacturing and experimental wartime engineering, the company developed a peerless classical music catalogue that showcased technological innovation alongside artistic accomplishment. This investigation focuses specifically on the contribution of the recording producer at Decca in creating this legacy, as can be illustrated by the career of Christopher Raeburn, the company’s most prolific producer and specialist in opera and vocal repertoire. It is the first study to examine Raeburn’s archive, and is supported with unpublished memoirs, private papers and recorded interviews with colleagues, collaborators and artists. Using these sources, the thesis considers the history and functions of the staff producer within Decca’s wider operational structure in parallel with the personal aspirations of the individual in exerting control, choice and authority on the process and product of recording. Having been recruited to Decca by John Culshaw in 1957, Raeburn’s fifty-year career spanned seminal moments of the company’s artistic and commercial lifecycle: from assisting in exploiting the dramatic potential of stereo technology in Culshaw’s Ring during the 1960s to his serving as audio producer for the 1990 The Three Tenors Concert international phenomenon. -

1 CRONOLOGÍA LICEÍSTA Se Incluye Un Listado Con Las

CRONOLOGÍA LICEÍSTA Se incluye un listado con las representaciones de Aida, de Giuseppe Verdi, en la historia del Gran Teatre del Liceu. Estreno absoluto: Ópera del Cairo, 24 de diciembre de 1871. Estreno en Barcelona: Teatro Principal, 16 abril 1876. Estreno en el Gran Teatre del Liceu: 25 febrero 1877 Última representación en el Gran Teatre del Liceu: 30 julio 2012 Número total de representaciones: 454 TEMPORADA 1876-1877 Número de representaciones: 21 Número histórico: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21. Fechas: 25 febrero / 3, 4, 7, 10, 15, 18, 19, 22, 25 marzo / 1, 2, 5, 10, 13, 18, 22, 27 abril / 2, 10, 15 mayo 1877. Il re: Pietro Milesi Amneris: Rosa Vercolini-Tay Aida: Carolina de Cepeda (febrero, marzo) Teresina Singer (abril, mayo) Radamès: Francesco Tamagno Ramfis: Francesc Uetam (febrero y 3, 4, 7, 10, 15 marzo) Agustí Rodas (a partir del 18 de marzo) Amonasro: Jules Roudil Un messaggiero: Argimiro Bertocchi Director: Eusebi Dalmau TEMPORADA 1877-1878 Número de representaciones: 15 Número histórico: 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36. Fechas: 29 diciembre 1877 / 1, 3, 6, 10, 13, 23, 25, 27, 31 enero / 2, 20, 24 febrero / 6, 25 marzo 1878. Il re: Raffaele D’Ottavi Amneris: Rosa Vercolini-Tay Aida: Adele Bianchi-Montaldo Radamès: Carlo Bulterini Ramfis: Antoine Vidal Amonasro: Jules Roudil Un messaggiero: Antoni Majjà Director: Eusebi Dalmau 1 7-IV-1878 Cancelación de ”Aida” por indisposición de Carlo Bulterini.