Sidney Homer, Song Composer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

029I-HMVCX1924XXX-0000A0.Pdf

This Catalogue contains all Double-Sided Celebrity Records issued up to and including March 31st, 1924. The Single-Sided Celebrity Records are also included, and will be found under the records of the following artists :-CLARA Burr (all records), CARUSO and MELBA (Duet 054129), CARUSO,TETRAZZINI, AMATO, JOURNET, BADA, JACOBY (Sextet 2-054034), KUBELIK, one record only (3-7966), and TETRAZZINI, one record only (2-033027). International Celebrity Artists ALDA CORSI, A. P. GALLI-CURCI KURZ RUMFORD AMATO CORTOT GALVANY LUNN SAMMARCO ANSSEAU CULP GARRISON MARSH SCHIPA BAKLANOFF DALMORES GIGLI MARTINELLI SCHUMANN-HEINK BARTOLOMASI DE GOGORZA GILLY MCCORMACK Scorn BATTISTINI DE LUCA GLUCK MELBA SEMBRICH BONINSEGNA DE' MURO HEIFETZ MOSCISCA SMIRN6FF BORI DESTINN HEMPEL PADEREWSKI TAMAGNO BRASLAU DRAGONI HISLOP PAOLI TETRAZZINI BI1TT EAMES HOMER PARETO THIBAUD CALVE EDVINA HUGUET PATTt WERRENRATH CARUSO ELMAN JADLOWKER PLANCON WHITEHILL CASAZZA FARRAR JERITZA POLI-RANDACIO WILLIAMS CHALIAPINE FLETA JOHNSON POWELL ZANELLIi CHEMET FLONZALEY JOURNET RACHM.4NINOFF ZIMBALIST CICADA QUARTET KNIIPFER REIMERSROSINGRUFFO CLEMENT FRANZ KREISLER CORSI, E. GADSKI KUBELIK PRICES DOUBLE-SIDED RECORDS. LabelRed Price6!-867'-10-11.,613,616/- (D.A.) 10-inch - - Red (D.B.) 12-inch - - Buff (D.J.) 10-inch - - Buff (D.K.) 12-inch - - Pale Green (D.M.) 12-inch Pale Blue (D.O.) 12-inch White (D.Q.) 12-inch - SINGLE-SIDED RECORDS included in this Catalogue. Red Label 10-inch - - 5'676 12-inch - - Pale Green 12-inch - 10612,615j'- Dark Blue (C. Butt) 12-inch White (Sextet) 12-inch - ALDA, FRANCES, Soprano (Ahl'-dah) New Zealand. She Madame Frances Aida was born at Christchurch, was trained under Opera Comique Paris, Since Marcltesi, and made her debut at the in 1904. -

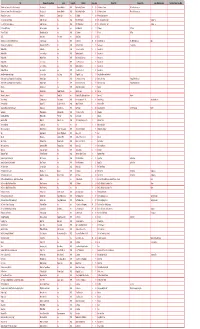

Louis Nicholas Song Collection

Title Composer/Arranger/Editor Lyricist Copyright Publisher Pages Box Original Title Translated Title Larger Work/Collection Translated Title of Large Work A Menina e a Cancao (Fillette et la Chanson, La) Villa-Lobos, H. Andrade, Mario de 1925 Max Eschig & Cie Edrs 12 25 A Menina e a Cancao Fillette et la Chanson, La A Menina e a Cancao (Fillette et la Chanson, La), c.2 Villa-Lobos, H. Andrade, Mario de 1925 Max Eschig & Cie Edrs 12 25 A Menina e a Cancao Fillette et la Chanson, La A Notre Dame sous-terre Chatillon, E. Chastel, Guy n/a E. Chatillon 7 30 A Notre Dame sous-terre A Te, O Cara, Amore Talora Bellini, Vincenzo n/a 1946 Pro Art Publications 4 29 A Te, O Cara, Amore Talora Puritans, The A Te, O Cara, Amore Talora, c.2 Bellini, Vincenzo n/a 1946 Pro Art Publications 4 29 A Te, O Cara, Amore Talora Puritans, The A Trianon (At Trianon) Holmes, Augusta n/a n/a Harch Music Co. 4 19 A Trianon At Trianon A Vous (To Thee) D'Hardelot and Boyer n/a 1895 G. Schirmer 4 17 A Vous To Thee A.B.C. Parry, John Parry, John n/a Oliver Ditson 5 23 A.B.C. Abborrita rivale, L' (She, My Rival Detested) Verdi, Giuseppe n/a 1915 G. Schirmer 10 28 Abborrita rivale, L' She, My Rival Detested Aida Abendsegen (Evening-Prayer) Humperdinck and Wette n/a 1894 B. Schott's Sohne 2 28 Abendsegen Evening-Prayer Abide with Me Ashford, E.L. -

Il Trovatore Was Made Stage Director Possible by a Generous Gift from Paula Williams the Annenberg Foundation

ilGIUSEPPE VERDItrovatore conductor Opera in four parts Marco Armiliato Libretto by Salvadore Cammarano and production Sir David McVicar Leone Emanuele Bardare, based on the play El Trovador by Antonio García Gutierrez set designer Charles Edwards Tuesday, September 29, 2015 costume designer 7:30–10:15 PM Brigitte Reiffenstuel lighting designed by Jennifer Tipton choreographer Leah Hausman The production of Il Trovatore was made stage director possible by a generous gift from Paula Williams The Annenberg Foundation The revival of this production is made possible by a gift of the Estate of Francine Berry general manager Peter Gelb music director James Levine A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, and the San Francisco principal conductor Fabio Luisi Opera Association 2015–16 SEASON The 639th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S il trovatore conductor Marco Armiliato in order of vocal appearance ferr ando Štefan Kocán ines Maria Zifchak leonor a Anna Netrebko count di luna Dmitri Hvorostovsky manrico Yonghoon Lee a zucena Dolora Zajick a gypsy This performance Edward Albert is being broadcast live on Metropolitan a messenger Opera Radio on David Lowe SiriusXM channel 74 and streamed at ruiz metopera.org. Raúl Melo Tuesday, September 29, 2015, 7:30–10:15PM KEN HOWARD/METROPOLITAN OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Verdi’s Il Trovatore Musical Preparation Yelena Kurdina, J. David Jackson, Liora Maurer, Jonathan C. Kelly, and Bryan Wagorn Assistant Stage Director Daniel Rigazzi Italian Coach Loretta Di Franco Prompter Yelena Kurdina Assistant to the Costume Designer Anna Watkins Fight Director Thomas Schall Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted by Cardiff Theatrical Services and Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Lyric Opera of Chicago Costume Shop and Metropolitan Opera Costume Department Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department Ms. -

Il Trovatore

Synopsis Act I: The Duel Count di Luna is obsessed with Leonora, a young noblewoman in the queen’s service, who does not return his love. Outside the royal residence, his soldiers keep watch at night. They have heard an unknown troubadour serenading Leonora, and the jealous count is determined to capture and punish him. To keep his troops awake, the captain, Ferrando, recounts the terrible story of a gypsy woman who was burned at the stake years ago for bewitching the count’s infant brother. The gypsy’s daughter then took revenge by kidnapping the boy and throwing him into the flames where her mother had died. The charred skeleton of a baby was discovered there, and di Luna’s father died of grief soon after. The gypsy’s daughter disappeared without a trace, but di Luna has sworn to find her. In the palace gardens, Leonora confides in her companion Ines that she is in love with a mysterious man she met before the outbreak of the war and that he is the troubadour who serenades her each night. After they have left, Count di Luna appears, looking for Leonora. When she hears the troubadour’s song in the darkness, Leonora rushes out to greet her beloved but mistakenly embraces di Luna. The troubadour reveals his true identity: He is Manrico, leader of the partisan rebel forces. Furious, the count challenges him to fight to the death. Act II: The Gypsy During the duel, Manrico overpowered the count, but some instinct stopped him from killing his rival. The war has raged on. -

Vlaamse Raad

VLAAMSE RAAD ZITTING 1982-1983 Nr. 17 BULLETIN VAN VRAGEN EN ANTWOORDEN 21 JUNI 1983 INHOUDSOPGAVE Blz. 1. VRAGEN VAN DE LEDEN EN ANTWOORDEN VAN DE REGERING A. Vragen waarop werd geantwoord binnen de reglementaire termijn (R.v.O. art. 65, 3 en 4) G. Geens, Voorzitter van de Vlaamse Executieve, Gemeenschapsminister van economie en werkgelegenheid . 535 K. Poma, Vice-Voorzitter van de Vlaamse Executieve, Gemeenschapsminis- ter van cultuur . 536 M. Galle, Gemeenschapsminister van binnenlandse aangelegenheden . 548 Mevrouw R. Steyaert, Gemeenschapsminister van gezin en welzijnszorg . 550 P. Akkermans, Gemeenschapsminister van ruimtelijke ordening, landinrich- ting en natuurbehoud . 550 J. Buchmann, Gemeenschapsminister van huisvesting . 552 B. Vragen waarop werd geantwoord na het verstrijken van de reglementaire termijn (R.v.O. art. 65, 5) Nihil . 553 II. VRAGEN WAAROP EEN VOORLOPIG ANTWOORD WERD GEGEVEN (R.v.O. art. 65, 6) K. Poma, Vice-voorzitter van de Vlaamse Executieve, Gemeenschapsmini- ster van cultuur . 553 III. VRAGEN WAAROP NIET WERD GEANTWOORD BINNEN DE REGLE- MENTAIRE TERMIJN (R.v.O. art. 65, 5) Nihil . 553 Rechtzetting . 554 Vlaamse Raad -Vragen en Antwoorden - Nr. 17 - 2 1 juni 1983 535 I. VRAGEN VAN DE LEDEN EN ANTWOOR- Dit Centrum bezit thans de juridische vorm van een DEN VAN DE REGERING vzw, waarvan de beheersorganen samengesteld zijn op pluralistische basis. A. Vragen waarop werd geantwoord binnende Sedert geruime tijd zijn besprekingen aan de gang die reglementaire termijn (R.v.O. art. 65, 3 en 4) er moeten toe leiden aan dit centrum een publiek- rechtelijk statuut te bezorgen. De aan te houden G. GEENS vorm van dit publiekrechtelijk statuut staat momen- VOORZITTER VAN DE VLAAMSE teel echter nog niet definitief vast. -

Toscanini IV – La Scala and the Metropolitan Opera

Toscanini IV – La Scala and the Metropolitan Opera Trying to find a balance between what the verbal descriptions of Toscanini’s conducting during the period of roughly 1895-1915 say of him and what he actually did can be like trying to capture lightning in a bottle. Since he made no recordings before December 1920, and instrumental recordings at that, we cannot say with any real certainty what his conducting style was like during those years. We do know, from the complaints of Tito Ricordi, some of which reached Giuseppe Verdi’s ears, that Italian audiences hated much of what Toscanini was doing: conducting operas at the written tempos, not allowing most unwritten high notes (but not all, at least not then), refusing to encore well-loved arias and ensembles, and insisting in silence as long as the music was being played and sung. In short, he instituted the kind of audience decorum we come to expect today, although of course even now (particularly in Italy and America, not so much in England) we still have audiences interrupting the flow of an opera to inject their bravos and bravas when they should just let well enough alone. Ricordi complained to Verdi that Toscanini was ruining his operas, which led Verdi to ask Arrigo Boïto, whom he trusted, for an assessment. Boïto, as a friend and champion of the conductor, told Verdi that he was simply conducting the operas pretty much as he wrote them and not allowing excess high notes, repeats or breaks in the action. Verdi was pleased to hear this; it is well known that he detested slowly-paced performances of his operas and, worse yet, the interpolated high notes he did not write. -

110266 Bk Gigli5 EU 19/05/2004 01:53Pm Page 5

110266 bk Gigli5 EU 19/05/2004 01:53pm Page 5 BIZET: Les pêcheurs de perles: 6 Tu che a Dio spiegasti l’ali (Act 3) 4:27 VERDI: Rigoletto: THOMAS: Mignon: ADD 1 Del tempio al limitar (Act 1) 4:27 Ezio Pinza, bass; Metropolitan Opera Chorus ! Bella figlia dell’amore (Act 3) 4:12 % Ah, non credevi tu (Act 3) 4:04 THE GIGLI EDITION • 5 Giuseppe De Luca, baritone Recorded 12th December 1927 Amelita Galli-Curci, soprano; Recorded 30th November 1928 8.110266 Recorded 28th November 1927 in Liederkranz Hall, New York Louise Homer, contralto; at 16 West 64th Street, New York in Liederkranz Hall, New York Matrix: CVE-41226-1 Giuseppe De Luca, baritone Matrix: CVE-45121-3 Matrix: CVE-41071-2 First issued on Victor 8096 Recorded 16th December 1927 First issued on Victor 6905 First issued on Victor 8084 in Liederkranz Hall, New York 7 Tombe degl’avi miei (Act 3) 4:46 Matrix: CVE-41233-1 ^ Addio, Mignon, fa core (Act 2) 3:07 PONCHIELLI: La Gioconda: Recorded 12th December 1927 First issued on Victor 10012 Recorded 30th November 1928 Beniamino 2 Enzo Grimaldo, Principe di Santafior! 4:30 in Liederkranz Hall, New York at 16 West 64th Street, New York (Act 1) Matrix: CVE-41227-2 VERDI: Rigoletto Matrix: CVE-45119-4 Giuseppe De Luca, baritone Unpublished on 78 rpm @ Bella figlia dell’amore (Act 3) 4:26 First issued on Victor 6905 GIGLI Recorded 28th November 1927 8 Giusto cielo, rispondete (Act 3) 3:54 Amelita Galli-Curci, soprano; in Liederkranz Hall, New York Ezio Pinza, bass; Metropolitan Opera Chorus Louise Homer, contralto; MEYERBEER: L’africaine: -

Enrico Caruso

NI 7924/25 Also Available on Prima Voce ENRICO CARUSO Opera Volume 3 NI 7803 Caruso in Opera Volume One NI 7866 Caruso in Opera Volume Two NI 7834 Caruso in Ensemble NI 7900 Caruso – The Early Years : Recordings from 1902-1909 NI 7809 Caruso in Song Volume One NI 7884 Caruso in Song Volume Two NI 7926/7 Caruso in Song Volume Three 12 NI 7924/25 NI 7924/25 Enrico Caruso 1873 - 1921 • Opera Volume 3 and pitch alters (typically it rises) by as much as a semitone during the performance if played at a single speed. The total effect of adjusting for all these variables is revealing: it questions the accepted wisdom that Caruso’s voice at the time of his DISC ONE early recordings was very much lighter than subsequently. Certainly the older and 1 CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA, Mascagni - O Lola ch’ai di latti la cammisa 2.50 more artistically assured he became, the tone became even more massive, and Rec: 28 December 1910 Matrix: B-9745-1 Victor Cat: 87072 likewise the high A naturals and high B flats also became even more monumental in Francis J. Lapitino, harp their intensity. But it now appears, from this evidence, that the baritone timbre was 2 LA GIOCONDA, Ponchielli - Cielo e mar 2.57 always present. That it has been missed is simply the result of playing the early discs Rec: 14 March 1910 Matrix: C-8718-1 Victor Cat: 88246 at speeds that are consistently too fast. 3 CARMEN, Bizet - La fleur que tu m’avais jetée (sung in Italian) 3.53 Rec: 7 November 1909 Matrix: C-8349-1 Victor Cat: 88209 Of Caruso’s own opinion on singing and the effort required we know from a 4 STABAT MATER, Rossini - Cujus animam 4.47 published interview that he believed it should be every singers aim to ensure ‘that in Rec: 15 December 1913 Matrix: C-14200-1 Victor Cat: 88460 spite of the creation of a tone that possesses dramatic tension, any effort should be directed in 5 PETITE MESSE SOLENNELLE, Rossini - Crucifixus 3.18 making the actual sound seem effortless’. -

10-06-2018 Aida Mat.Indd

Synopsis Act I Egypt, during the reign of the pharaohs. At the royal palace in Memphis, the high priest Ramfis tells the warrior Radamès that Ethiopia is preparing another attack against Egypt. Radamès hopes to command the Egyptian army. He is in love with Aida, the Ethiopian slave of Princess Amneris, the king’s daughter, and he believes that victory in the war would enable him to free and marry her. But Amneris also loves Radamès and is jealous of Aida, whom she suspects of being her rival for Radamès’s affection. A messenger brings news that the Ethiopians are advancing. The king names Radamès to lead the army, and all prepare for war. Left alone, Aida is torn between her love for Radamès and loyalty to her native country, where her father, Amonasro, is king. In the temple of Vulcan, the priests consecrate Radamès to the service of the god Ptah. Ramfis orders Radamès to protect the homeland. Act II Ethiopia has been defeated, and in her chambers, Amneris waits for the triumphant return of Radamès. Alone with Aida, she pretends that Radamès has fallen in battle, then says that he is still alive. Aida’s reactions leave no doubt that she loves Radamès. Amneris is certain that she will defeat her rival. At the city gates, the king and Amneris observe the victory celebrations and praise Radamès’s triumph. Soldiers lead in the captured Ethiopians, among them Amonasro, who signals his daughter not to reveal his identity as king. Amonasro’s eloquent plea for mercy impresses Radamès, and the warrior asks that the order for the prisoners to be executed be overruled and that they be freed instead. -

The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection a Handlist

The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection A Handlist A wide-ranging collection of c. 4000 individual popular songs, dating from the 1920s to the 1970s and including songs from films and musicals. Originally the personal collection of the singer Rita Williams, with later additions, it includes songs in various European languages and some in Afrikaans. Rita Williams sang with the Billy Cotton Club, among other groups, and made numerous recordings in the 1940s and 1950s. The songs are arranged alphabetically by title. The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection is a closed access collection. Please ask at the enquiry desk if you would like to use it. Please note that all items are reference only and in most cases it is necessary to obtain permission from the relevant copyright holder before they can be photocopied. Box Title Artist/ Singer/ Popularized by... Lyricist Composer/ Artist Language Publisher Date No. of copies Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Dans met my Various Afrikaans Carstens- De Waal 1954-57 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Careless Love Hart Van Steen Afrikaans Dee Jay 1963 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Ruiter In Die Nag Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1963 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Van Geluk Tot Verdriet Gideon Alberts/ Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1970 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Wye, Wye Vlaktes Martin Vorster/ Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1970 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs My Skemer Rapsodie Duffy -

MA Thesis: Linguistics: English Language and Linguistics

MA thesis: Linguistics: English Language and Linguistics Sean de Goede S0871346 First reader: Tony Foster Second reader: Lettie Dorst Leiden University Faculty of Humanities Department of Linguistics 08-06-2015 Language Switches in Eurovision Song Contest Lyrics 1 The Stylistics of Language Switches in Lyrics of Entries of the Eurovision Song Contest MA thesis: Linguistics: English Language and Linguistics Sean de Goede S0871346 First reader: Tony Foster Second reader: Lettie Dorst Leiden University Faculty of Humanities Department of Linguistics 08-06-2015 Language Switches in Eurovision Song Contest Lyrics 2 Acknowledgements It did not come as a surprise to the people around me when I told them that the subject for my Master’s thesis was going to be based on the Eurovision Song Contest. Ever since I was a little boy I have been a fan, and some might even say that I became somewhat obsessed, for which I cannot really blame them. Moreover, I have always had a special interest in mixed language songs, so linking the two subjects seemed only natural. Thanks to a rather unfortunate turn of events, this thesis took a lot longer to write than was initially planned, but nevertheless, here it is. Special thanks are in order for my supervisor, Tony Foster, who has helped me in many ways during this time. I would also like to thank a number of other people for various reasons. The second reader Lettie Dorst. My mother, for being the reason I got involved with the Eurovision Song Contest. My father, for putting up with my seemingly endless collection of Eurovision MP3s in the car. -

Eljnral Mtttntt £>*Rt?0 3

UNIVERSITY- MUSICAL-SOCIETY (Eljnral Mtttntt £>*rt?0 3 Forty-Seventh Season Seventh Concert Vo* ?S —————No. CCCCXXXXII Complete Series — p « Detroit Symphony Orchestra •* OSSIP GABRILOWITSCH, Conducting •HUl Aufcttnrtam. Atm Arbor, IHirtjigan /^ MONDAY, MARCH 8, 1926, AT EIGHT O'CLOCK PROGRAM J| as Overture to the Opera "Oberon" Weber Fifth Symphony in C minor, Op. 67 Beethoven Allegro con brio Andante con moto 8$ Allegro (Scherzo); Trio Allegro Prelude and Love Death from the Opera "Tristan and Isolde"... Wagner <*§ Capriccio Espagnol, Op. 34 Rimsky-Korsakov J§i Alborada Jj£$ Variazioni Rfo Alborada j*g Scena e conto gitano c™ Fandango asturiano 85 (OVER) $£ raffftfft K^ AR Sa ON G A'VITA'BREVI S j ^^5^t^«^^5 THIRTY-THIRD ANNUAL MAY FESTIVAL EARL V. MOORE, Musical Director Six Concerts Four Days May 19, 20, 21, 22 ARTISTS, ORGANIZATIONS, AND PROGRAMS (Subject to Change) First Concert—Wednesday Evening, May 19 SOLOISTS LOUISE HOMER Contralto Metropolitan and Chicago Civic Operas CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Frederick Stock, Conductor PROGRAM OVERTURE, "Im Fruhling" Goldmark ARIA MMU. HOMSR SYMPHONY IN B MINOR Chausson Intermission ARIA MME. HOMER "THE PLANETS" .Hoist ARIA MME. HOMER DANCES FROM "PRINCE IGOR" Bbrodine Second Concert—Thursday Evening, May 20 SOLOISTS MARIE SUNDELIUS Soprano Metropolitan Opera JEANNE LAVAL Contralto American Oratorio Singer CHARLES STRATTON Tenor Distinguished American Artist THEODORE HARRISON Baritone Authoratative "Elijah" UNIVERSITY CHORAL UNION ) _ . ,7 „ r , . CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA f hMl W' Moore> Conductor PROGRAM ELIJAH Mendelssohn An Oratorio with words from Holy Script CAST Theodore Harrison Elijah Marie Sundelius The Widow Charles Stratton Obadiah Jeanne Laval An Angel Third Concert—Friday Afternoon, May 21 SOLOISTS ALBERT SPAULDING Violinist CHILDREN'S FESTIVAL CHORUS J.