10-06-2018 Aida Mat.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

029I-HMVCX1924XXX-0000A0.Pdf

This Catalogue contains all Double-Sided Celebrity Records issued up to and including March 31st, 1924. The Single-Sided Celebrity Records are also included, and will be found under the records of the following artists :-CLARA Burr (all records), CARUSO and MELBA (Duet 054129), CARUSO,TETRAZZINI, AMATO, JOURNET, BADA, JACOBY (Sextet 2-054034), KUBELIK, one record only (3-7966), and TETRAZZINI, one record only (2-033027). International Celebrity Artists ALDA CORSI, A. P. GALLI-CURCI KURZ RUMFORD AMATO CORTOT GALVANY LUNN SAMMARCO ANSSEAU CULP GARRISON MARSH SCHIPA BAKLANOFF DALMORES GIGLI MARTINELLI SCHUMANN-HEINK BARTOLOMASI DE GOGORZA GILLY MCCORMACK Scorn BATTISTINI DE LUCA GLUCK MELBA SEMBRICH BONINSEGNA DE' MURO HEIFETZ MOSCISCA SMIRN6FF BORI DESTINN HEMPEL PADEREWSKI TAMAGNO BRASLAU DRAGONI HISLOP PAOLI TETRAZZINI BI1TT EAMES HOMER PARETO THIBAUD CALVE EDVINA HUGUET PATTt WERRENRATH CARUSO ELMAN JADLOWKER PLANCON WHITEHILL CASAZZA FARRAR JERITZA POLI-RANDACIO WILLIAMS CHALIAPINE FLETA JOHNSON POWELL ZANELLIi CHEMET FLONZALEY JOURNET RACHM.4NINOFF ZIMBALIST CICADA QUARTET KNIIPFER REIMERSROSINGRUFFO CLEMENT FRANZ KREISLER CORSI, E. GADSKI KUBELIK PRICES DOUBLE-SIDED RECORDS. LabelRed Price6!-867'-10-11.,613,616/- (D.A.) 10-inch - - Red (D.B.) 12-inch - - Buff (D.J.) 10-inch - - Buff (D.K.) 12-inch - - Pale Green (D.M.) 12-inch Pale Blue (D.O.) 12-inch White (D.Q.) 12-inch - SINGLE-SIDED RECORDS included in this Catalogue. Red Label 10-inch - - 5'676 12-inch - - Pale Green 12-inch - 10612,615j'- Dark Blue (C. Butt) 12-inch White (Sextet) 12-inch - ALDA, FRANCES, Soprano (Ahl'-dah) New Zealand. She Madame Frances Aida was born at Christchurch, was trained under Opera Comique Paris, Since Marcltesi, and made her debut at the in 1904. -

Libretto Nabucco.Indd

Nabucco Musica di GIUSEPPE VERDI major partner main sponsor media partner Il Festival Verdi è realizzato anche grazie al sostegno e la collaborazione di Soci fondatori Consiglio di Amministrazione Presidente Sindaco di Parma Pietro Vignali Membri del Consiglio di Amministrazione Vincenzo Bernazzoli Paolo Cavalieri Alberto Chiesi Francesco Luisi Maurizio Marchetti Carlo Salvatori Sovrintendente Mauro Meli Direttore Musicale Yuri Temirkanov Segretario generale Gianfranco Carra Presidente del Collegio dei Revisori Giuseppe Ferrazza Revisori Nicola Bianchi Andrea Frattini Nabucco Dramma lirico in quattro parti su libretto di Temistocle Solera dal dramma Nabuchodonosor di Auguste Anicet-Bourgeois e Francis Cornu e dal ballo Nabucodonosor di Antonio Cortesi Musica di GIUSEPPE V ERDI Mesopotamia, Tavoletta con scrittura cuneiforme La trama dell’opera Parte prima - Gerusalemme All’interno del tempio di Gerusalemme, i Leviti e il popolo lamen- tano la triste sorte degli Ebrei, sconfitti dal re di Babilonia Nabucco, alle porte della città. Il gran pontefice Zaccaria rincuora la sua gente. In mano ebrea è tenuta come ostaggio la figlia di Nabucco, Fenena, la cui custodia Zaccaria affida a Ismaele, nipote del re di Gerusalemme. Questi, tuttavia, promette alla giovane di restituirle la libertà, perché un giorno a Babilonia egli stesso, prigioniero, era stato liberato da Fe- nena. I due innamorati stanno organizzando la fuga, quando giunge nel tempio Abigaille, supposta figlia di Nabucco, a comando di una schiera di Babilonesi. Anch’essa è innamorata di Ismaele e minaccia Fenena di riferire al padre che ella ha tentato di fuggire con uno stra- niero; infine si dichiara disposta a tacere a patto che Ismaele rinunci alla giovane. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

CCF 18-27 RELEASE: September 24, 2018 The

COLLECTORS’ CORNER with HENRY FOGEL Broadcast Schedule - Fall 2018 PROGRAM #: CCF 18-27 RELEASE: September 24, 2018 The Art of Sergei Lemeshev – Program 1 A program of arias and songs sung by the great Russian tenor (1902‐1977). Please consult cue sheet for details. PROGRAM #: CCF 18-28 RELEASE: October 1, 2018 The Art of Sergei Lemeshev – Program 2 A program of arias and songs sung by the great Russian tenor (1902‐1977). Please consult cue sheet for details. PROGRAM #: CCF 18-29 RELEASE: October 8, 2018 Music by Josef Suk – Program 1 All pieces composed by Josef Suk. Please consult cue sheet for details. Fantasy for Violin and Orchestra (Pamela Frank, violin; Sir Charles Mackerras, conductor; Czech Philharmonic Orchestra) Meditation on Saint Wenceslas (Rafael Kubelik, conductor; Czech Philharmonic Orchestra) Minuet, Op.21 (Ignaz Friedman, piano) Praga (Libor Pesek, conductor; Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra) A Summer’s Tale (Jiri Belohlavek, conductor; BBC Symphony Orchestra) PROGRAM #: CCF 18-30 RELEASE: October 15, 2018 Music by Josef Suk – Program 2 All pieces composed by Josef Suk. Please consult cue sheet for details. Symphony in C Minor for large orchestra, Op. 27, “Asrael” (Vaclav Talich, conductor; Czech Philharmonic Orchestra) The Ripening, Symphonic Poem, Op. 34 (Vaclav Talich, conductor; Czech Philharmonic Orchestra) Four pieces for violin and piano, Op. 17, “Burleska” (Nathan Milstein, violin; Artur Balsam, piano) Pieces for Violin and Piano, Op. 17, no. 2, “Appassionata” (Ginette Neveu, violin; Bruno Seidler‐Winkler, piano) PROGRAM #: CCF 18-31 RELEASE: October 22, 2018 Music by Ernest Bloch – Program 1 All pieces composed by Ernest Bloch. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Contact: Kathy Kahn

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press contact: Kathy Kahn, [email protected], 510-418-8523 Theater contact: Harriet Schlader, [email protected], 510-531-9597 Woodminster Summer Musicals AUGUST 2015 -- CALENDAR INFORMATION WHAT: The Producers PERFORMED BY: Woodminster Summer Musicals by Producers Associates, Inc. WHERE: Woodminster Amphitheater in Joaquin Miller Park, 3300 Joaquin Miller Road, Oakland WHEN: August 7-16, 2015 PERFORMANCES: August 7, 8, 9, 13, 14, 15, 16 - 8 p.m. TICKETS: 510-531-9597, or www.woodminster.com, $28-$59 (Discounts for children, seniors, groups) PREVIEW PERFORMANCE: August 6, 8 p.m., All tickets $18 at the door. (Since it's a rehearsal, the show may be stopped to solve technical problems.) A New Mel Brooks Musical, Book by Mel Brooks and Thomas Meehan, Music and Lyrics by Mel Brooks, Based on the 1968 Film, Original direction and choreography by Susan Stroman, Produced by arrangement with Music Theatre International. Photo caption: Greg Carlson* as Max Bialystock, Melissa Reinerston as Ulla, and John Tichenor* as Leo Bloom. PRESS RELEASE The Producers Opens August 7 at Woodminster Summer Musicals Stage Musical is Adapted from Mel Brooks' Classic Comedy Film July 20, 2015, Oakland, CA -- Producers Associates, Inc. announces that the 2015 season of Woodminster Summer Musicals will continue with The Producers, the hit Broadway musical based on the 1968 Mel Brooks film of the same name. It will run August 7-16 at Woodminster Amphitheater in Oakland's Joaquin Miller Park, located at 3300 Joaquin Miller Road in the Oakland hills. The Producers tells the story of a down-on-his-luck Broadway producer and his nervous accountant, who together come up with a scheme to make a million dollars (each) by producing the worst flop in Broadway history. -

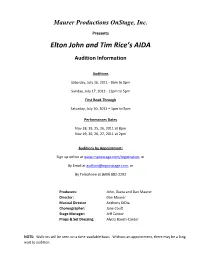

Elton John and Tim Rice's AIDA

Maurer Productions OnStage, Inc. Presents Elton John and Tim Rice’s AIDA Audition Information Auditions Saturday, July 16, 2011 - 9am to 5pm Sunday, July 17, 2011 - 12pm to 5pm First Read-Through Saturday, July 30, 2011 – 1pm to 5pm Performances Dates Nov 18, 19, 25, 26, 2011 at 8pm Nov 19, 20, 26, 27, 2011 at 2pm Auditions by Appointment: Sign up online at www.mponstage.com/registration, or By Email at [email protected], or By Telephone at (609) 882-2292 Producers: John, Diana and Dan Maurer Director: Dan Maurer Musical Director Anthony DiDia Choreographer: Jane Coult Stage Manager: Jeff Cantor Props & Set Dressing: Alycia Bauch-Cantor NOTE: Walk-ins will be seen on a time-available basis. Without an appointment, there may be a long wait to audition. Auditions for Elton John & Tim Rice’s AIDA Index 1. About the Show 2. Available Roles 3. What You Need to Know About the Audition 4. Audition Application 5. Calendar for Conflicts 6. Musical Numbers 7. Audition Monologues 1 Elton John and Tim Rice’s Aida Directed by Dan Maurer Part Broadway musical, part dance spectacular and part rock concert, AIDA is an epic tale about the power and timelessness of love. The show features over twenty roles for singers, dancers, and actors of various races and will be staged by the award winning production team that brought shows like Man of La Mancha and Singin’ in the Rain to Kelsey Theatre. Winner of four Tony Awards when Disney’s Hyperion Theatrical Group first brought it to Broadway, AIDA features music by pop legend Elton John and lyrics by Tim Rice, who wrote the lyrics for hit shows like Jesus Christ Superstar and Evita. -

1 CRONOLOGÍA LICEÍSTA Se Incluye Un Listado Con Las

CRONOLOGÍA LICEÍSTA Se incluye un listado con las representaciones de Aida, de Giuseppe Verdi, en la historia del Gran Teatre del Liceu. Estreno absoluto: Ópera del Cairo, 24 de diciembre de 1871. Estreno en Barcelona: Teatro Principal, 16 abril 1876. Estreno en el Gran Teatre del Liceu: 25 febrero 1877 Última representación en el Gran Teatre del Liceu: 30 julio 2012 Número total de representaciones: 454 TEMPORADA 1876-1877 Número de representaciones: 21 Número histórico: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21. Fechas: 25 febrero / 3, 4, 7, 10, 15, 18, 19, 22, 25 marzo / 1, 2, 5, 10, 13, 18, 22, 27 abril / 2, 10, 15 mayo 1877. Il re: Pietro Milesi Amneris: Rosa Vercolini-Tay Aida: Carolina de Cepeda (febrero, marzo) Teresina Singer (abril, mayo) Radamès: Francesco Tamagno Ramfis: Francesc Uetam (febrero y 3, 4, 7, 10, 15 marzo) Agustí Rodas (a partir del 18 de marzo) Amonasro: Jules Roudil Un messaggiero: Argimiro Bertocchi Director: Eusebi Dalmau TEMPORADA 1877-1878 Número de representaciones: 15 Número histórico: 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36. Fechas: 29 diciembre 1877 / 1, 3, 6, 10, 13, 23, 25, 27, 31 enero / 2, 20, 24 febrero / 6, 25 marzo 1878. Il re: Raffaele D’Ottavi Amneris: Rosa Vercolini-Tay Aida: Adele Bianchi-Montaldo Radamès: Carlo Bulterini Ramfis: Antoine Vidal Amonasro: Jules Roudil Un messaggiero: Antoni Majjà Director: Eusebi Dalmau 1 7-IV-1878 Cancelación de ”Aida” por indisposición de Carlo Bulterini. -

Il Trovatore Was Made Stage Director Possible by a Generous Gift from Paula Williams the Annenberg Foundation

ilGIUSEPPE VERDItrovatore conductor Opera in four parts Marco Armiliato Libretto by Salvadore Cammarano and production Sir David McVicar Leone Emanuele Bardare, based on the play El Trovador by Antonio García Gutierrez set designer Charles Edwards Tuesday, September 29, 2015 costume designer 7:30–10:15 PM Brigitte Reiffenstuel lighting designed by Jennifer Tipton choreographer Leah Hausman The production of Il Trovatore was made stage director possible by a generous gift from Paula Williams The Annenberg Foundation The revival of this production is made possible by a gift of the Estate of Francine Berry general manager Peter Gelb music director James Levine A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, and the San Francisco principal conductor Fabio Luisi Opera Association 2015–16 SEASON The 639th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S il trovatore conductor Marco Armiliato in order of vocal appearance ferr ando Štefan Kocán ines Maria Zifchak leonor a Anna Netrebko count di luna Dmitri Hvorostovsky manrico Yonghoon Lee a zucena Dolora Zajick a gypsy This performance Edward Albert is being broadcast live on Metropolitan a messenger Opera Radio on David Lowe SiriusXM channel 74 and streamed at ruiz metopera.org. Raúl Melo Tuesday, September 29, 2015, 7:30–10:15PM KEN HOWARD/METROPOLITAN OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Verdi’s Il Trovatore Musical Preparation Yelena Kurdina, J. David Jackson, Liora Maurer, Jonathan C. Kelly, and Bryan Wagorn Assistant Stage Director Daniel Rigazzi Italian Coach Loretta Di Franco Prompter Yelena Kurdina Assistant to the Costume Designer Anna Watkins Fight Director Thomas Schall Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted by Cardiff Theatrical Services and Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Lyric Opera of Chicago Costume Shop and Metropolitan Opera Costume Department Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department Ms. -

Ernest Guiraud: a Biography and Catalogue of Works

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1990 Ernest Guiraud: A Biography and Catalogue of Works. Daniel O. Weilbaecher Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Weilbaecher, Daniel O., "Ernest Guiraud: A Biography and Catalogue of Works." (1990). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4959. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4959 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Bellini's Norma

Bellini’s Norma - A discographical survey by Ralph Moore There are around 130 recordings of Norma in the catalogue of which only ten were made in the studio. The penultimate version of those was made as long as thirty-five years ago, then, after a long gap, Cecilia Bartoli made a new recording between 2011 and 2013 which is really hors concours for reasons which I elaborate in my review below. The comparative scarcity of studio accounts is partially explained by the difficulty of casting the eponymous role, which epitomises bel canto style yet also lends itself to verismo interpretation, requiring a vocalist of supreme ability and versatility. Its challenges have thus been essayed by the greatest sopranos in history, beginning with Giuditta Pasta, who created the role of Norma in 1831. Subsequent famous exponents include Maria Malibran, Jenny Lind and Lilli Lehmann in the nineteenth century, through to Claudia Muzio, Rosa Ponselle and Gina Cigna in the first part of the twentieth. Maria Callas, then Joan Sutherland, dominated the role post-war; both performed it frequently and each made two bench-mark studio recordings. Callas in particular is to this day identified with Norma alongside Tosca; she performed it on stage over eighty times and her interpretation casts a long shadow over. Artists since, such as Gencer, Caballé, Scotto, Sills, and, more recently, Sondra Radvanovsky have had success with it, but none has really challenged the supremacy of Callas and Sutherland. Now that the age of expensive studio opera recordings is largely over in favour of recording live or concert performances, and given that there seemed to be little commercial or artistic rationale for producing another recording to challenge those already in the catalogue, the appearance of the new Bartoli recording was a surprise, but it sought to justify its existence via the claim that it authentically reinstates the integrity of Bellini’s original concept in matters such as voice categories, ornamentation and instrumentation. -

Il Trovatore

Synopsis Act I: The Duel Count di Luna is obsessed with Leonora, a young noblewoman in the queen’s service, who does not return his love. Outside the royal residence, his soldiers keep watch at night. They have heard an unknown troubadour serenading Leonora, and the jealous count is determined to capture and punish him. To keep his troops awake, the captain, Ferrando, recounts the terrible story of a gypsy woman who was burned at the stake years ago for bewitching the count’s infant brother. The gypsy’s daughter then took revenge by kidnapping the boy and throwing him into the flames where her mother had died. The charred skeleton of a baby was discovered there, and di Luna’s father died of grief soon after. The gypsy’s daughter disappeared without a trace, but di Luna has sworn to find her. In the palace gardens, Leonora confides in her companion Ines that she is in love with a mysterious man she met before the outbreak of the war and that he is the troubadour who serenades her each night. After they have left, Count di Luna appears, looking for Leonora. When she hears the troubadour’s song in the darkness, Leonora rushes out to greet her beloved but mistakenly embraces di Luna. The troubadour reveals his true identity: He is Manrico, leader of the partisan rebel forces. Furious, the count challenges him to fight to the death. Act II: The Gypsy During the duel, Manrico overpowered the count, but some instinct stopped him from killing his rival. The war has raged on.