MA Thesis: Linguistics: English Language and Linguistics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogo De Canciones 27/05/2021 21:55:57

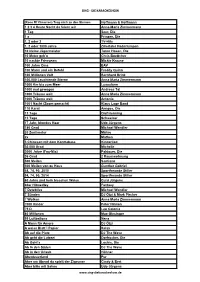

CATALOGO DE CANCIONES 27/05/2021 21:55:57 IDIOMA: Español CODIGO INTERPRETE TITULO ES20456 A.B. QUINTANILLA AMOR PROHIBIDO ES20467 A.B. QUINTANILLA COMO LA FLOR ES9591 ABBA CHIQUITITA (ESPAÑOL) ES10381 ABBA FERNANDO(ESPAÑOL) ES10829 ABBA GRACIAS A LA MUSICA ES10444 ABBA MAMMA MIA (EN ESPAÑOL) ES10486 ABBA MIX ABBA MUSICAL ES2395 ABBA SAN FERNANDO ES11093 ABEL PINOS TANTO AMOR ES11747 ABEL PINTOS & MALU ONCEMIL ES7028 ABIGAIL DESDE EL ACANTILADO ES10394 ABIGAIL GITANO ES3512 ABIGAIL ORO Y PLATA ES10373 ABRAHAM MATEO ESTA NAVIDAD ES LA MAS BELLA ES10554 ABRAHAM MATEO SEÑORITA ES11298 ABRAHAM MATEO WHEN YOU LOVE SOMEBODY ES11735 ABRAHAM MATEO & AUSTIN HABLAME BAJITO MAHONE & 50 CENT ES11806 ABRAHAM MATEO & JENNIFER SE ACABO EL AMOR LOPEZ ES11645 ABRAHAM MATEO FT FARRUKO, LOCO ENAMORADO CHRISTIAN DANIEL ES2874 ACUSTICA AMOR PROHIBIDO ES8201 ADAMO A LO GRANDE ES5109 ADAMO ALINE ES8210 ADAMO CAE LA NIEVE ES8301 ADAMO CANTARE ES1214 ADAMO COMO LAS ROSAS ES1220 ADAMO DULCE PAOLA ES3926 ADAMO ELLA ES8952 ADAMO ELLA ANDA ES1752 ADAMO EN BANDOLERA ES8321 ADAMO ERA UNA LINDA FLOR ES6519 ADAMO ES MI VIDA ES9316 ADAMO INCH ALLAH ES8092 ADAMO LA NOCHE ES2039 ADAMO MI GRAN NOCHE ES7914 ADAMO MI ROOL ES1508 ADAMO MIS MANOS EN TU CINTURA ES2237 ADAMO MUY JUNTOS ES2481 ADAMO PORQUE YO QUIERO ES4366 ADAMO QUE EL TIEMPO SE DETENGA Page 1 CODIGO INTERPRETE TITULO ES9884 ADAMO QUIERO ES1783 ADAMO TU NOMBRE ES5995 ADAMO UN MECHON DE SU CABELLO ES5196 ADAMO UNA LAGRIMA EN LAS NUBES ES8373 ADAMO YO TE OFREZCO ES21118 ADOLESCENTE ORQUESTA EN AQUEL LUGAR ES21175 -

Reflections 3 Reflections

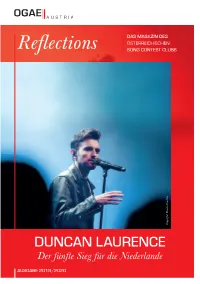

3 Refl ections DAS MAGAZIN DES ÖSTERREICHISCHEN Refl ections SONG CONTEST CLUBS AUSGABE 2019/2020 AUSGABE | TAUSEND FENSTER Der tschechische Sänger Karel Gott („Und samkeit in der großen Stadt beim Eurovision diese Biene, die ich meine, die heißt Maja …“) Song Contest 1968 in der Royal Albert Hall wurde vor allem durch seine vom böhmischen mit nur 2 Punkten den bescheidenen drei- SONG CONTEST CLUBS Timbre gekennzeichneten, deutschsprachigen zehnten Platz, fi ndet aber bis heute großen Schlager in den 1970er und 1980er Jahren zum Anklang innerhalb der ESC-Fangemeinde. Liebling der Freunde eingängiger U-Musik. Neben der deutschen Version, nahm Karel Copyright: Martin Krachler Ganz zu Beginn seiner Karriere wurde er Gott noch eine tschechische Version und zwei ÖSTERREICHISCHEN vom Österreichischen Rundfunk eingela- englische Versionen auf. den, die Alpenrepublik mit der Udo Jürgens- Hier seht ihr die spanische Ausgabe von „Tau- DUNCAN LAURENCE Komposition „Tausend Fenster“ zu vertreten. send Fenster“, das dort auf Deutsch veröff ent- Zwar erreichte der Schlager über die Ein- licht wurde. MAGAZINDAS DES Der fünfte Sieg für die Niederlande DIE LETZTE SEITE | ections Refl AUSGABE 2019/2020 2 Refl ections 4 Refl ections 99 Refl ections 6 Refl ections IMPRESSUM MARKUS TRITREMMEL MICHAEL STANGL Clubleitung, Generalversammlung, Organisation Clubtreff en, Newsletter, Vorstandssitzung, Newsletter, Tickets Eurovision Song Contest Inlandskorrespondenz, Audioarchiv [email protected] Fichtestraße 77/18 | 8020 Graz MARTIN HUBER [email protected] -

Edición Impresa

Mª Antonia Nicole La familia Sánchez Habichuela Arranca en Kidman Se estrena un Roland Garros Será la bruja documental derrotando de Embrujada sobrelasaga a la campeona en el cine flamenca Página 11 Página 20 Página 18 Los jóvenes sevillanos pierden oído antes de El primer diario que no se vende tiempo por los cascos Martes 24 MAYO DE 2005. AÑO VI. NÚMERO 1260 Los veinteañeros captan diez decibelios menos que sus padres. Los primeros problemas de sordera aparecen a los 40, veinte años antes. El 78% de la contaminación Abierto el plazo para obtener plaza en uno de los campamentos de verano acústica de Sevilla procede del tráfico. Las calles del centro, las más ruidosas. 2 Hay 34 campings con actividades programadas pa- ra niños y jóvenes desde los 8 a los 30 años. 4 Amenaza con volar su domicilio Larevista El suceso fue motivado porque le habían reclamado una deuda pendiente. Fue detenido por los Geos. 3 Las peluquerías de Sevilla, las más caras de Andalucía Hasta 55 euros por el tinte cuando la media es de 25, según un estudio realizado entre 160 establecimientos de toda Andalucía. FOTO: C.R. 3 SERGIO GONZÁLEZ YA ES VERANOEN 20 MINUTOS Los cuatro niños que murieron en el ESPAÑA EN EUROVISIÓN accidente de Sigüenza iban sin cinturón Twelve points, zero points Las cuatro niñas del otro coche, que resultaron Un repaso a la Bikinis coloridos º heridas, sí lo llevaban puesto. 9 1 Massiel (1968) y Salomé (1969). participación 2º Karina (71), Mocedades (73), Betty española en el Caen tres etarras en Francia, uno de los Missiego (79) y Anabel Conde (95). -

Webarts.Com.Cy Loreen Euphoria

webarts.com.cy Social Monitor Report Loreen Euphoria Overall Results 500 425 375 250 125 75 5/24 5/25 5/26 1,670 Total Mentions 1,592 Positive 556.67 Mentions / Day 21 Neutral 97.0 Average Sentiment 57 Negative 97.0 Date Source Author Content 5/26/2012 Twitter marcus_fletcher RT @_Trademark_: Trademark's tip for Eurovision this evening (Positive) is Euphoria by Loreen for Sweden. Englebert's song is a load of rubbish. #Eurovision - twitter.com 5/26/2012 Twitter hechulera #np Euphoria-Loreen - twitter.com (Positive) 5/26/2012 Twitter terrycambelbal Euphoria-Loreen... my winner of this evening ! :) I know she will (Positive) made it. - twitter.com 5/26/2012 Twitter egochic Ey! #Europe lets #vote for #SWEDEN and our amazing (Positive) #LOREEN tonite. #EUPHORIA is the #BEST song in years #ESC12 #ESC2012 #Eurovision #WINNING - twitter.com 5/26/2012 Twitter oksee_l We're going u-u-u-u-u-up...Euphoria!!!!! #ESC2012 #esc12se (Positive) #eurovision #Loreen12p #sweden #Loreen - twitter.com 5/26/2012 Twitter berrie69 "Loreen - Euphoria (Acoustic Version) live at Nobel Brothers (Positive) Museum in Baku" http://t.co/C0ycCR69 - twitter.com 5/26/2012 Twitter mahejter RT @HladnaTastatura: See ya next year in Stockholm... (Positive) #NowPlaying Loreen - Euphoria - twitter.com 5/26/2012 Twitter garthy2008 DJGarthy: Loreen - Euphoria http://t.co/xXj4j8Il - twitter.com (Positive) 5/26/2012 Twitter nicoletterancic Loreen Euphoria (Sweden Eurovision Song Contest 2012) (Positive) COVER http://t.co/Oz6AyPFd via @youtube Please watch and share,thanx :** - twitter.com Webarts Ltd 2012 © All rights reserved Page 1 of 38 webarts.com.cy Social Monitor Report (continued) Date Source Author Content 5/26/2012 Twitter elliethepink @bbceurovision i'll be eating a #partyringbiscuit every time (Positive) Sweden score "douze pointes". -

TAUNO HANNIKAISEN ÄÄNITEARKISTO Ryhmä 1

TAUNO HANNIKAISEN ÄÄNITEARKISTO Ryhmä 1. Järjestetty kelanauhaan merkityn numeron mukaan Ryhmä 1.a) nauhat nro 1-341, 167 kpl * Chicago symphony orchestra johtajanaan Tauno Hannikainen nauhan numero sisältö muita tietoja signum reel no, subject, date 1,1 Bruckner: Sinfonia V Leo Funtek - Kaupungin a000001 orkesteri 16.1.1953 2, BR HAN, 10.49 Prokofiev: "Ala ja Lolly" -sarja a000002 Respighi: Pini di Roma Sibelius: Aallottaret Satu (HKO) 3, BR HAN, 10.49 Dohnanyi: Ruralia Hungarica a000003 (Dohnanyi) Bruckner: Symphony no 9 D-minor (Hausegger - München) 1,2 and 3 movement 4, BR HAN, 10.49 Luigini: Egyptiläinen baletti, III osan Chicago symphony a000004 loppu ja IV osa orchestra J.Strauss: Waltz, "Doreschwalben aus oestterreich" J.Strauss: Tick-tack polka, op. 365 Schubert: Serenade Tschaikowsky: Finale: Allegro con fuoco, from symphony no. 4, F minor, opus 36 5, BR HAN, 11.49 Smetana: Mein Vaterland a000005 6, 1958 Aarre Merikanto: Sinfonia III 21.9.58 a000006 Vivaldi - Dalla Piccola: Sonaatti T.H. Helsinki alttoviululle (Primrose) 7, BR HAN, 11.49 Nielsen: Sinfonia II, Die vier a000007 Temperamente Ringbom: Sinfonia III 8, BR HAN, 11.49 * Mendelssohn-Bartholdy: War Priests a000008 March, opus 74 Weber: Invitation to the Dance Offenbach: Overture, "Orpheus in the Underworld" Delibes: Waltz and Czardas "Coppelia" Tschaikowsky: Overture-Fantasia "Romeo and Juliet" 9, BR HAN, 11.49 Mendelssohn: Sinfonia IV, 11/49 a000009 viimeinen osa Respighi: Roman Festivals Merikanto: Ukri 10, BR HAN, 11.49 *Bach-Abert: Prelude, Chorale 12/49 a000010 and Fugue *Massanet: Scenes Pittoresques *Glinka: Overture to "Russian and Ludmilla" R.Strauss: Der Rosenkavalier Waltzes, ar: Doebber 11, BR HAN, 12.49 *Rossini: Overture to "The Barber 12/49 a000011 of Seville" *R. -

Hallowell Weekly Register

An Independent Journal, Devoted to Home Interests. Established in 1878. ■ . ..................................................- ................................. ...................... .. __________________________________ _________________________________‘' " A V O L U M E 21. HALLOWELL, ME., SATURDAY, JULY 30, 1898. N V HGoV = ------- 2 samv LIQUOR IN THE ARMY. tary posts in which the younger soldiers ure. A few smaller buildings are un BAD ENGLISH THE M AN VHO COMJRrument are being schooled for the National de finished and some of the larger ones are 5ND. ig mi The contrast between the order of Spring and Summer fense. The canteen system, says the re not full of exhibits. The great organ There would be both interest and in a General Miles against the use of intoxi port, should be abolished. On this sub stands with half its pipes in, and work struction in a list of the words securely In the discussion of the ^ cants by soldiers exposed to the hard ject it quotes the testimony of Major- men and mortar beds are visible here intrenched in our own vocabulary to-day Spani h territory after tl> ships of the Cuban campaign, and the General Howard, who speaks as,follows: and there. Y’et as such tilings go, the which were bitterly assaulted on their one im <ortani influence! ’ order of the Spanish captains that extra Ever since the prospect of sending an fair may he called open and a success. first appearance. Swift praises himself wha ignored Strangi grog should be served to the sailors to army to our Southern border and prob It will pay many an Eastern man to for his valiant effort against certain of bondholder ha6 been o\ SUITS AND OVERCOATS, fortify them for the fight or flight in ably to Cuba has been made apparent to these intruders: “I have done my ut the famous Yew Yorki visit it. -

Rezension Im Erweiterten Forschungskontext: ESC 2016

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Christoph Oliver Mayer Rezension im erweiterten Forschungskontext: ESC 2016 https://doi.org/10.17192/ep2016.1.4446 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Rezension / review Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Mayer, Christoph Oliver: Rezension im erweiterten Forschungskontext: ESC. In: MEDIENwissenschaft: Rezensionen | Reviews, Jg. 33 (2016), Nr. 1. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17192/ep2016.1.4446. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung 3.0/ Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Attribution 3.0/ License. For more information see: Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ Hörfunk und Fernsehen 99 Rezension im erweiterten Forschungskontext: ESC Christine Ehardt, Georg Vogt, Florian Wagner (Hg.): Eurovision Song Contest: Eine kleine Geschichte zwischen Körper, Geschlecht und Nation Wien: Zaglossus 2015, 344 S., ISBN 9783902902320, EUR 19,95 Der Sieg von Conchita Wurst beim Triebel 2011; Goldstein/Taylor 2013) Eurovision Song Contest (ESC) 2014 sowie von einzelnen Wissenschaft- und die sich daran anschließenden ler_innen unterschiedlicher Disziplinen europaweiten Diskussionen um Tole- (z.B. Sieg 2013; Mayer 2015) angesto- ranz und Gleichberechtigung haben ßen wurden. eine ganze Palette von Publikationen Gemeinsam ist all den neueren über den bedeutendsten Populärmusik- Ansätzen ein gesteigertes Interesse für Wettbewerb hervorgerufen (z.B. Wol- Körperinszenierungen, Geschlech- ther/Lackner 2014; Lackner/Rau 2015; terrollen und Nationsbildung, denen Vogel et al. 2015; Kennedy O’Connor sich auch der als „kleine Geschichte“ 2015; Vignoles/O’Brien 2015). Nur untertitelte Sammelband der Wie- wenige wissenschaftliche Monografien ner Medienwissenschaftler_innen (z.B. -

L'italia E L'eurovision Song Contest Un Rinnovato

La musica unisce l'Europa… e non solo C'è chi la definisce "La Champions League" della musica e in fondo non sbaglia. L'Eurovision è una grande festa, ma soprattutto è un concorso in cui i Paesi d'Europa si sfidano a colpi di note. Tecnicamente, è un concorso fra televisioni, visto che ad organizzarlo è l'EBU (European Broadcasting Union), l'ente che riunisce le tv pubbliche d'Europa e del bacino del Mediterraneo. Noi italiani l'abbiamo a lungo chiamato Eurofestival, i francesi sciovinisti lo chiamano Concours Eurovision de la Chanson, l'abbreviazione per tutti è Eurovision. Oggi più che mai una rassegna globale, che vede protagonisti nel 2016 43 paesi: 42 aderenti all'ente organizzatore più l'Australia, che dell'EBU è solo membro associato, essendo fuori dall'area (l’anno scorso fu invitata dall’EBU per festeggiare i 60 anni del concorso per via dei grandi ascolti che la rassegna fa in quel paese e che quest’anno è stata nuovamente invitata dall’organizzazione). L'ideatore della rassegna fu un italiano: Sergio Pugliese, nel 1956 direttore della RAI, che ispirandosi a Sanremo volle creare una rassegna musicale europea. La propose a Marcel Bezençon, il franco-svizzero allora direttore generale del neonato consorzio eurovisione, che mise il sigillo sull'idea: ecco così nascere un concorso di musica con lo scopo nobile di promuovere la collaborazione e l'amicizia tra i popoli europei, la ricostituzione di un continente dilaniato dalla guerra attraverso lo spettacolo e la tv. E oltre a questo, molto più prosaicamente, anche sperimentare una diretta in simultanea in più Paesi e promuovere il mezzo televisivo nel vecchio continente. -

Country Christmas ...2 Rhythm

1 Ho li day se asons and va ca tions Fei er tag und Be triebs fe rien BEAR FAMILY will be on Christmas ho li days from Vom 23. De zem ber bis zum 10. Ja nuar macht De cem ber 23rd to Ja nuary 10th. During that peri od BEAR FAMILY Weihnach tsfe rien. Bestel len Sie in die ser plea se send written orders only. The staff will be back Zeit bitte nur schriftlich. Ab dem 10. Janu ar 2005 sind ser ving you du ring our re gu lar bu si ness hours on Mon- wir wie der für Sie da. day 10th, 2004. We would like to thank all our custo - Bei die ser Ge le gen heit be dan ken wir uns für die gute mers for their co-opera ti on in 2004. It has been a Zu sam men ar beit im ver gan ge nen Jahr. plea su re wor king with you. BEAR FAMILY is wis hing you a Wir wünschen Ihnen ein fro hes Weih nachts- Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. fest und ein glüc kliches neu es Jahr. COUNTRY CHRISTMAS ..........2 BEAT, 60s/70s ..................86 COUNTRY .........................8 SURF .............................92 AMERICANA/ROOTS/ALT. .............25 REVIVAL/NEO ROCKABILLY ............93 OUTLAWS/SINGER-SONGWRITER .......25 PSYCHOBILLY ......................97 WESTERN..........................31 BRITISH R&R ........................98 WESTERN SWING....................32 SKIFFLE ...........................100 TRUCKS & TRAINS ...................32 INSTRUMENTAL R&R/BEAT .............100 C&W SOUNDTRACKS.................33 C&W SPECIAL COLLECTIONS...........33 POP.............................102 COUNTRY CANADA..................33 POP INSTRUMENTAL .................108 COUNTRY -

Sing - Die Karaokeshow

SING - DIE KARAOKESHOW (Rose Of Cimarron) Trag mich zu den Sternen Hoffmann & Hoffmann 1 2 3 4 Heute Nacht da feiern wir Anna-Maria Zimmermann 1 Tag Seer, Die 1 x Prinzen, Die 1, 2 oder 3 TV-Hits 1, 2 oder 3000 Jahre Zillertaler Haderlumpen 10 kleine Jägermeister Toten Hosen, Die 10 Meter geh'n Chris Boettcher 10 nackte Friseusen Mickie Krause 100 Jahre Oma EAV 100 Mann und ein Befehl Freddy Quinn 100 Millionen Volt Bernhard Brink 100.000 Leuchtende Sterne Anna Maria Zimmermann 1000 Km bis zum Meer Luxuslärm 1000 mal gewogen Andreas Tal 1000 Träume weit Anna Maria Zimmermann 1000 Träume weit Antonia 1001 Nacht (Zoom gemacht) Klaus Lage Band 110 Karat Amigos, Die 13 Tage Olaf Henning 13 Tage Schweizer 17 Jahr, blondes Haar Udo Jürgens 180 Grad Michael Wendler 20 Zentimeter Möhre 2x Mathea 3 Chinesen mit dem Kontrabass Kinderlied 30.000 Grad Michelle 3000 Jahre (Fox-Mix) Paldauer, Die 36 Grad 2 Raumwohnung 500 Meilen Santiano 500 Meilen von zu Haus Gunther Gabriel 54, 74, 90, 2010 Sportfreunde Stiller 54, 74, 90, 2014 Sportfreunde Stiller 60 Jahre und kein bisschen Weise Curd Jürgens 60er Hitmedley Fantasy 7 Detektive Michael Wendler 7 Sünden DJ Ötzi & Mark Pircher 7 Wolken Anna Maria Zimmermann 7000 Rinder Peter Hinnen 75 D Leo Colonia 80 Millionen Max Giesinger 99 Luftballons Nena A Mann für Amore DJ Ötzi A weiss Blatt´l Papier Relax Ab auf die Piste DJ The Wave Ab geht die Lutzzzi Dorfrocker, Die Ab Geht’s Lochis, Die Ab in den Süden DJ The Wave Ab in den Urlaub Höhner Abenteuerland Pur Aber am Abend da spielt der Zigeuner Cindy & Bert -

Malta “To Dream Again” Lynn Chircopp

Austria “Man is the measure of all things” Alf Poier Austria’s entry this year at first appears mediocre, with notable Austrian music critic, Marie Herberstein describing it as “a stinker”. Closer inspection however, reveals a more complex story behind Alf Poier, a story likely to appeal to the biologically minded. The lyrical genius behind lines such as: “I like most animals on this earth, but I really prefer little rabbits and bears” and “Whoever wants to know more about animals should study Biology or inform himself on my homepage” more than makes up for the lack of melody. Perhaps criticizing the competitive nature of the entire Eurovision establishment, Poier states: “The difference between animals such as apes and primates is no bigger than between noodles and pasta” This kind of anti-establishment jibe is unlikely to win him any favours from the judges. Belgium “Sanomi” Urban Trad I like the cut of Urban Trad’s jib. They are combining traditional folk tunes with a more modern rhythm, and it works. Perhaps they are playing a very Celtic sounding tune because of Ireland’s success through Eurovision history. Perhaps Flemish folk music sounds like this too. Perhaps the greatest surprise with Urban Trad is that they have invented an “imaginary and thus universal language” for their song. With current pushes for unity in Europe, perhaps this will resound strongly with the judges. Croatia “Vise Nisam Tvoja” Claudia Beni Seventeen year-old hairdressing student, Claudia Beni will be disappointing many young European boys when she proclaims to the Latvian audience “I can’t be your lover”. -

Pdf Liste Totale Des Chansons

40ú Comórtas Amhrán Eoraifíse 1995 Finale - Le samedi 13 mai 1995 à Dublin - Présenté par : Mary Kennedy Sama (Seule) 1 - Pologne par Justyna Steczkowska 15 points / 18e Auteur : Wojciech Waglewski / Compositeurs : Mateusz Pospiezalski, Wojciech Waglewski Dreamin' (Révant) 2 - Irlande par Eddie Friel 44 points / 14e Auteurs/Compositeurs : Richard Abott, Barry Woods Verliebt in dich (Amoureux de toi) 3 - Allemagne par Stone Und Stone 1 point / 23e Auteur/Compositeur : Cheyenne Stone Dvadeset i prvi vijek (Vingt-et-unième siècle) 4 - Bosnie-Herzégovine par Tavorin Popovic 14 points / 19e Auteurs/Compositeurs : Zlatan Fazlić, Sinan Alimanović Nocturne 5 - Norvège par Secret Garden 148 points / 1er Auteur : Petter Skavlan / Compositeur : Rolf Løvland Колыбельная для вулкана - Kolybelnaya dlya vulkana - (Berceuse pour un volcan) 6 - Russie par Philipp Kirkorov 17 points / 17e Auteur : Igor Bershadsky / Compositeur : Ilya Reznyk Núna (Maintenant) 7 - Islande par Bo Halldarsson 31 points / 15e Auteur : Jón Örn Marinósson / Compositeurs : Ed Welch, Björgvin Halldarsson Die welt dreht sich verkehrt (Le monde tourne sens dessus dessous) 8 - Autriche par Stella Jones 67 points / 13e Auteur/Compositeur : Micha Krausz Vuelve conmigo (Reviens vers moi) 9 - Espagne par Anabel Conde 119 points / 2e Auteur/Compositeur : José Maria Purón Sev ! (Aime !) 10 - Turquie par Arzu Ece 21 points / 16e Auteur : Zenep Talu Kursuncu / Compositeur : Melih Kibar Nostalgija (Nostalgie) 11 - Croatie par Magazin & Lidija Horvat 91 points / 6e Auteur : Vjekoslava Huljić