'Abdu'l-Bahá in Egypt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

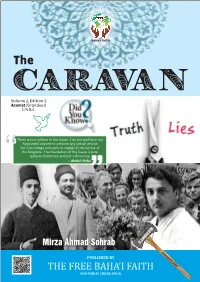

The Caravan V2 E2 for EXPORT

The Way of Freedom is opened! Hasten ye! The Way of Freedom is opened! Hasten ye! The Fountain of Knowledge is gushing! Drink ye! Say, O Friends: The Tabernacle of Oneness is raised; look not upon each other with the eye of strangeness. Ye are all the fruits of one tree and the leaves of one branch. Truly, I say: whatever lessens ignorance and increases knowledge, that has been, is and shall be accepted by the Creator. Baha'u'llah (Baha'i Scriptures, pages 132-133) THE CARAVAN || REVIVED EDITION : VOLUME 2 || AZAMAT 175 B.E 1. Exhibit of the New History Society and the Caravan at the New York World Fair in the year 1939 The Goal of its existance was to spread the teachings of the Baha'i faith. 2. THE CARAVAN || REVIVED EDITION : VOLUME 2 || AZAMAT 175 B.E FOREWORD It is with Divine Blessings and your continued support in the form of an overwhelming response to our small efforts, that we are today presenting the Third Edition of this effort to spread the pristine message of God, which is Love !! The divine words of the Great Manifestation are soothing to the hearts of the believers and thus it is our core purpose to inspire the faithful to walk on the path of righteousness and enlightenment. The recently concluded month of fasting gave us a much needed spiritual boost by creating a divine connection between ourselves and the light of the Manifestation. The festival of Ridvan reminds us of the Holy days when believers would gather in the Garden of Ridvan in Baghdad, Iraq to congratulate and meet the Manifestation of God for 12 days. -

Baha'ism in Iran

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 9, Issue 2 (Mar. - Apr. 2013), PP 53-61 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.Iosrjournals.Org Baha’ism in Iran Ashaq Hussain Centre of Central Asian Studies, University of Kashmir, Hazratbal-190006 Abstract : During the early 19th century, a religious movement called Babism flourished in Persia though for a short period, i:e., 1844-1852. Its founder Mirza Ali Mohammad Shirazi proclaimed his station as that of the Mehdi to the Muslims. Afterwards Bab claimed Prophetic status. He abrogated Islamic law and instead promulgated a system of Babi law in his (Persian) Bayan. Although the Babi movement successfully established its network both in rural and urban settlements of Iran, and after the execution of Bab he became a prominent figure among Babis. Most of the Babis were exiled by the Qachar government to the Sunni Ottoman area in Iraq. It was in Iraq that Baha‟u‟llah proclaimed himself the Prophet Promised by Bab. Majority of the Babis believed him and entered into the new faith and became Baha‟is. This happened in 1863 after a decade of Bab‟s execution. He stated his own dispensation and wrote letters to many kings instigating them to establish peace. He tried a lot to make his laws compatible with the modern globalized world. To him “World is but one country and humankind its citizens”. So far as the relevance of the present study is concerned, its pros and cons need to be analyzed and evaluated objectively. Study of religion usually influences common people in so far as the legitimate force that operates behind the principles and ideals of religion are concerned. -

Episodes in the Life of MONEEREH KHANUM

Episodes in the Life of Munirih Khanum's Account Introductory Words MONEEREH KHANUM In the Name of Abha the Most Glorious By MONEEREH KHANUM In accord with the request of a number of spiritual sisters and the maid-servants of God in the West, I herein write down a brief account of my own life, and its relation to this great Revelation. O Thou Almighty! Thou dost testify and art a witness that all my limbs, organs, heart, soul and conscience bear testimony to Thy inexhaustible bounties; for, from the beginning of my life, without any merit on my part, Thou didst shower the rains of Thy Favor upon this maid-servant of Thy Threshold. From the beginning of my life, and during the Foreword period of my childhood, there have come into A few months ago, Moneereh Khanum - the wife my life wonders - each one of which is a miracle, of Abdul Baha, and, as she is known throughout causing great astonishment. Were I to explain the Bahai world by the title of "the Holy Mother," every incident fully, and to thank with my tongue mailed to me a Persian manuscript recording every blessing vouchsafed, I should be unable therein, in her inimitable way, some of the most to go on with this account, and it would lead to charming and intimate accounts of her eventful prolixity. and sacred life. The manuscript was From the age of twelve to the day when I stood accompanied with a letter written by Moneereh in the Holy Presence 1, and visited the Blessed Khanum and Shoghi Effendi, offering me the Shrine 2, I have had many dreams which are privilege of translating and publishing it for the worthy of record, conducing man to awareness; benefit of the friends. -

The Eternal Quest for God: an Introduction to the Divine Philosophy of `Abdu'l-Bahá Julio Savi

The Eternal Quest for God: An Introduction to the Divine Philosophy of `Abdu'l-Bahá Julio Savi George Ronald, Publisher 46 High Street, Kidlington, Oxford OX5 2DN Copyright © Julio Savi, 1989 All rights Reserved British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Savi, Julio The eternal quest for God: an introduction to the divine philosophy of `Abdu'l-Bahá. I. Bahaism. Abd al Baha ibn Baha All ah, 1844-1921. I. Title II. Nell'universo sulle tracce di Dio. English 297'.8963 ISBN 0-85398-295-3 Printed in Great Britain by Billing and Sons Ltd, Worcester By the same author Nell'universo sulle tracce di Dio (EDITRICE NÚR, ROME, 1988) Bahíyyih Khánum, Ancella di Bahá (CASA EDITRICE BAHÁ'Í, ROME, 1983) To my father Umberto Savi with love and gratitude I am especially grateful to Continental Counselor Dr. Leo Niederreiter without whose loving encouragement this book would have not been written Chapter 1 return to Table of Contents Notes and Acknowledgements Italics are used for all quotations from the Bahá'í Sacred Scriptures, namely `any part of the writings of the Báb, Bahá'u'lláh and the Master'. (Letter on behalf of Shoghi Effendi, in Seeking the Light of the Kingdom (comp.), p.17.) Italics are not used for recorded utterances by `Abdu'l- Bahá. Although very important for the concepts and the explanations they convey, when they have `in one form or the other obtained His sanction' (Shoghi Effendi, quoted in Principles of Bahá'í Administration, p.34) - as is the case, for example, with Some Answered Questions or The Promulgation of Universal Peace - they cannot `be considered Scripture'. -

The Bahá'í Faith and Wicca

The Bahá’í Faith and Wicca - A Comparison of Relevance in Two Emerging Religions by Lil Osborn Abstract The purpose of this paper is to make comparisons between the growth and potential for further development of the Bahá’í Faith and Wicca in Britain. This study uses the Theory of Relevance developed by Sperber and Wilson to explain cognition in the field of linguistics and applied to the field of religious studies by the author in an earlier work. The paper begins by outlining the milieu in which both traditions began and notes possible overlaps of individuals and networks. It continues by contrasting motifs of beliefs and values between the two systems and investigates the history of both by arguing that relevance is the driving force in their respective development. Thus, the Bahá’í Faith which began by attracting radical and progressive elements gradually became more conservative as its principles became generally accepted and its legalistic structure ensured the upholding of traditional concepts of family and sexuality. Conversely, the interaction with feminism and the ecology movement caused Wiccans to embrace a radical and inclusive perspective which was not present in the inception of Gardnerian tradition. Finally, the potential for growth and influence of both traditions is assessed within the context of the Theory of Relevance. Introduction This genesis of this paper was the introduction of a course on Wicca which caused me to peruse some of the literature outlining the life and work of Gerald Gardner and the re- emergence (or -

Christmas 2015 Issue 652 Editor: Gary Waugh

h eatheler Christmas 2015 Issue 652 Editor: Gary Waugh Deadline for letters, articles and other contributions for the next issue: 15th January 2015 Burrows Lea Wellness Talks CRYSTAL HEALING MINI WORKSHOP Thurs 10th March 2016 - 2.00pm contents An exploration of the spirit of crystals using ancient techniques & intuitive connection 4 Good Will To All Men for Healing, Balance and Relaxation! With Stella & Phyllis McCarthy 6 Healing Services Stella & Phyllis will take a very ‘hands-on’ approach and will help you to discover for 7 70 Years Of The Sanctuary yourself the joy of working with crystals. 9 At Christmas Time Crystals to work with will be available but please bring your own pendulum if you have one. 12 From Healing To Reflexology The talk is free but donations much 19 A Light Shining For All appreciated SPACE IS LIMITED SO PLEASE CONTACT 22 Time Is All Time CAROLYN LOW TO RESERVE A PLACE ON 01483 203540 OR EMAIL [email protected] 24 Happiness 27 The Healing Tree For further information on this and other 28 The Healing Continues Burrows Lea Wellness Talks, please see our website: www.harryedwardshealingsanctuary.org.uk 29 Health & Safety At Christmas join us now - become a friend! In return for your £25 annual subscription, you will receive a Friends Membership Card, a twice yearly Friends Newsletter, a £5 reduction in the charge for a normal healing appointment in our healing rooms, a 10% reduction in the cost of items purchased from our shop and, from time to time, invitations to specific Friends events at the Sanctuary. -

Rne Oocnen Blaoe

rne oocneN BLAOe Work an^ Worklessriess Japan cund ifie Wesi The Golden Blade THIRTY-SIXTH (1984) ISSUE CONTENTS E d i t o r i a l N o t e s A . B . 3 Elemental Beings and Human Destinies Rudolf Sieiner 20 WORK AND WORKLESSNESS The Meaning of Work Marjo van Boescholen 33 W o r k & D e s t i n y P e t e r R o t h 40 A New Vocation: Eurythmy Glenda Monasch 44 The Actor Alan Poolman 50 What is a Research Worker? Michael Wilson 55 A Dustman Speaks Greg Richey 62 Tinker, Tailor, Banker, Teacher William Forward 66 A D o c t o r s A p p r o a c h J e n n y J o s e p h s o n 75 The Satisfactions of Computer Programming .... Gail Kahovic 79 I Am a Plumber Jon Humbertstone 83 A C o o k ' s D e l i g h t W e n d y C o o k 86 Counselling & Priesthood Adam Bittleston 90 J A P A N A N D T H E W E S T Twenty-seven Haiku translated by R. H. Blyth 95 Individuality & Community in Japan TomieAndo and Terry Boardman 98 Japan and the World Economy Daniel T. Jones 117 Kotodama: The Speech Formation of Japan Tadahiro Ohnuma 129 Notes on Japanese Painting John Meeks 135 MESSENGERS OF THE LIGHT W e l l e s l e y T u d o r P o l e C h a r l e s D a v y 140 Alan Cottrell's "Goethe's View of Evil" reviewed by Owen Barfield 149 Edited by Adam Bittleston and Daniel T. -

Abdu'l-Bahá in Edinburgh

Abdu'l-Bahá in Edinburgh The Diary of Ahmad Sohrab 6 Jan 1913 - 10 Jan 1913 ??? (Unfamiliar) Place, Person, or Thing - if it is something Abdu'l-Bahá in Edinburgh familiar you don't need to read this footnote; eg. N.Y. Version: 2012.03.23 [ Diary Text: 2011.11.12 ] would be footnoted as New York Latest Version: iii Trivial Info; eg a footnote to a train would give train speeds www.paintdrawer.co.uk/david/folders/Spirituality/001=Bahai at the time. /Sohrab%20Diary%20Edinburgh.pdf NNN Names an unnamed reference to a person; eg "The Sohrab's Diary: 5 Jan 1913 - 10 Jan 1913 with additions, Persian Ambassador" would give his name. notes and appendices. ^^^ After a footnote number indicates a prior footnote to the same thing Overview v After a footnote number indicates a subsequent footnote to the same thing The Diary RRR Reference (used at the end of an additional account); eg an account might have a reference giving "Star of the What follows, is a very detailed account of Abdu'l-Bahá's visit West" and its volume, date and page number. to Edinburgh by Ahmad Sohrab, who was amongst Abdu'l- XXX Correction to something stated (eg he states Abdu'l-Baha Bahá's entourage, and also His translator. The Diary takes the is going to Oxford but not to deliver an address, but as it form of letters written every night around midnight after each turns out on the day He does so). long and tiring day, on 7 Charlotte Square headed paper, to £££ Gives equivalent in modern money. -

Man of Marvels – Clarence Bicknell

MAN OF MARVELS – CLARENCE BICKNELL A Talk by Renchi Bicknell Together with Marcus, Susie and Vanessa Bicknell Given to The Glastonbury Positive Living Group November 15th 2018 Renchi Bicknell, the writer of this presentation made in Glastonbury in November 2018, is the great grand nephew of Clarence Bicknell. Read more about him and the context of this talk at the end of the paper. “Welcome be to every guest, Come he North South East or West”... Words of hospitality painted alongside orange lilies in Clarence Bicknell’s mountain house The Casa Fontanalba where we shall return later... This evening I hope to share something of the story of my Great Great Uncle Clarence and even touch on a connection to Glastonbury and the Blue Bowl through Dr John Arthur Goodchild. Yesterday 140 years ago Clarence noted in his diary that he “dined with Dr Goodchild at the Grand Hotel” ...that was in November 1878. Dr Goodchild was 27 and Clarence had just celebrated his 37th birthday. Both were starting new posts in Bordighera - Clarence as chaplain to the Anglican Church and John Goodchild as the English doctor. Both were about to embark on different transformational journeys. It is amazing to think that in 20 years time Clarence would be discovering many thousands of rock engravings in the Alpes Maritimes and that Dr Goodchild would be completing his inspirational Celtic work “The Light of the West”. Then most dramatically in 1897 on his way back to Bordighera, Man of Marvels – Clarence Bicknell Renchi Bicknell, Nov 2018 1 staying at the St. -

'Abdu'l-Bahá Y La Religión Bahá'í

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials dʼinvestigació i docència en els termes establerts a lʼart. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix lʼautorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No sʼautoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes dʼexplotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des dʼun lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc sʼautoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. 32 del Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (RDL 1/1996). Para otros usos se requiere la autorización previa y expresa de la persona autora. En cualquier caso, en la utilización de sus contenidos se deberá indicar de forma clara el nombre y apellidos de la persona autora y el título de la tesis doctoral. -

Dion Fortune and Her Inner Plane Contacts: Intermediaries in the Western Esoteric Tradition

1 Dion Fortune and her Inner Plane Contacts: Intermediaries in the Western Esoteric Tradition Volume 1 of 2 Submitted by John Selby to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology June 2008 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from this thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has been previously submitted and approved for the award of a degree at this or any other University. 2 _________________________ Abstract Whereas occultists of the standing of H. P. Blavatsky, Annie Besant, C. W. Leadbeater, and especially Aleister Crowley have been well served by academic enquiry and by published accounts of their lives and work, Violet Evans, neé Firth (aka ‘Dion Fortune’), has suffered comparative neglect, as has her concept of the ‘Masters’ who inspired and informed her work. These factors, alongside the longevity of her Society of the Inner Light (still flourishing), are the catalysts for my embarking on this thesis. Chapter 1 discusses the method of approach, covers Fortune’s definitions of frequent occult terms, and compares observations of her work by fellow occultists and outside observers. Chapter 2 is a comprehensive review of mainly recent academic research into the role of intermediaries in magic and religion from ancient times, and serves as a background to Fortune’s own esoteric philosophy, showing that she was heir to a tradition with a long history. -

Writing on the Ground

Writing on the Ground by Wellesley Tudor Pole London: Neville Spearman Ltd, 1968 WITH COMMENTARIES BY WALTER LANG LONDON NEVILLE SPEARMAN First published in Great Britain by Neville Spearman Ltd Whitfield Street, London, W.l (c) 1968 by Wellesley Tudor Pole Foreword Introduction by the same author The Silent Road Man See Afar Private Dowding CONTENTS Foreword 7 Introduction 9 Part One 1. Jesus Writes 21 2. "And as Jesus Passed By . ." 33 3. At Supper 40 4. The Word 62 5. The Problem of Prophecy 74 Part Two 6. Some Links 87 7. The Archangelic Hierarchy 90 8. The Michael Tor, Glastonbury 97 9. The Closing Days of Atlantis 101 10. Does History Repeat Itself? 105 11. Prophecy in Relation to the Day of the Lord 109 12. Chivalry 114 13. Questionnaire 118 I4. "And With No Language But a Cry" 129 Part Three 15. The Bahá'í Faith 135 16. Personal Recollections (Abdu'l Bahá Abbas) 140 17. "Ye are all the Fruits of One Tree" 145 18. The Fall of Haifa (The Safeguarding of Abdu'l Bahá and His Family) 152 19. The Master as a Seer 156 20. The Prison House at St. Jean D'Acre (Extract from a letter written in November 1918) 160 21. Vision on the Mount 166 Epilogue 167 FOREWORD Is life extinguished by death or does it continue beyond the grave? The very act of living poses this question and the answer we arrive at—consciously or unconsciously—influences our every thought and every action throughout our lives. In this book, as in other books by Tudor Pole, this question is neither posed nor answered explicitly.