No Substitute for Kindness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commemorating the Overseas-Born Victoria Cross Heroes a First World War Centenary Event

Commemorating the overseas-born Victoria Cross heroes A First World War Centenary event National Memorial Arboretum 5 March 2015 Foreword Foreword The Prime Minister, David Cameron The First World War saw unprecedented sacrifice that changed – and claimed – the lives of millions of people. Even during the darkest of days, Britain was not alone. Our soldiers stood shoulder-to-shoulder with allies from around the Commonwealth and beyond. Today’s event marks the extraordinary sacrifices made by 145 soldiers from around the globe who received the Victoria Cross in recognition of their remarkable valour and devotion to duty fighting with the British forces. These soldiers came from every corner of the globe and all walks of life but were bound together by their courage and determination. The laying of these memorial stones at the National Memorial Arboretum will create a lasting, peaceful and moving monument to these men, who were united in their valiant fight for liberty and civilization. Their sacrifice shall never be forgotten. Foreword Foreword Communities Secretary, Eric Pickles The Centenary of the First World War allows us an opportunity to reflect on and remember a generation which sacrificed so much. Men and boys went off to war for Britain and in every town and village across our country cenotaphs are testimony to the heavy price that so many paid for the freedoms we enjoy today. And Britain did not stand alone, millions came forward to be counted and volunteered from countries around the globe, some of which now make up the Commonwealth. These men fought for a country and a society which spanned continents and places that in many ways could not have been more different. -

SA Police Gazette 1879

This sampler file contains various sample pages from the product. Sample pages will often include: the title page, an index, and other pages of interest. This sample is fully searchable (read Search Tips) but is not FASTFIND enabled. To view more samplers click here www.gould.com.au www.archivecdbooks.com.au · The widest range of Australian, English, · Over 1600 rare Australian and New Zealand Irish, Scottish and European resources books on fully searchable CD-ROM · 11000 products to help with your research · Over 3000 worldwide · A complete range of Genealogy software · Including: Government and Police 5000 data CDs from numerous countries gazettes, Electoral Rolls, Post Office and Specialist Directories, War records, Regional Subscribe to our weekly email newsletter histories etc. FOLLOW US ON TWITTER AND FACEBOOK www.unlockthepast.com.au · Promoting History, Genealogy and Heritage in Australia and New Zealand · A major events resource · regional and major roadshows, seminars, conferences, expos · A major go-to site for resources www.familyphotobook.com.au · free information and content, www.worldvitalrecords.com.au newsletters and blogs, speaker · Free software download to create biographies, topic details · 50 million Australasian records professional looking personal photo books, · Includes a team of expert speakers, writers, · 1 billion records world wide calendars and more organisations and commercial partners · low subscriptions · FREE content daily and some permanently This sampler file includes the title page and various sample pages from this volume. This file is fully searchable (read search tips page) but is not FASTFIND enabled South Australian Police Gazette 1879-80 Ref. AU5103-1880 ISBN: 978 1 921371 97 4 This book was kindly loaned to Archive CD Books Australia by South Australia Police Historical Society http://www.sapolicehistory.org/ Navigating this CD To view the contents of this CD use the bookmarks and Adobe Reader’s forward and back buttons to browse through the pages. -

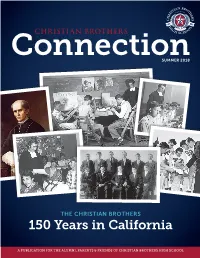

Connection – Summer 2018

ConnectionCHRISTIAN BROTHERS SUMMER 2018 THE CHRISTIAN BROTHERS 150 Years in California A PUBLICATION FOR THE ALUMNI, PARENTS & FRIENDS OF CHRISTIAN BROTHERS HIGH SCHOOL CB Leadership Team Lorcan P. Barnes President Chris Orr Principal June McBride Board of Trustees Director of Finance David Desmond ’94 The Board of Trustees at Christian Brothers High School is comprised of 11 volunteers Assistant Principal dedicated to safeguarding and advancing the school’s Lasallian Catholic college preparatory mission. Before joining the Board of Trustees, candidates undergo Michelle Williams training on Lasallian charism (history, spirituality and philosophy of education) and Assistant Principal Policy Governance, a model used by Lasallian schools throughout the District of Myra Makelim San Francisco New Orleans. In the 2017–18 school year, the board welcomed two new Human Resources Director members, Marianne Evashenk and Heidi Harrison. David Walrath serves in the role of chair and Mr. Stephen Mahaney ’69 is the vice chair. Kristen McCarthy Director of Admissions & The Policy Governance model comprises an inclusive, written set of goals for the school, Communications called Ends Policies, which guide the board in monitoring the performance of the school through the President/CEO. Ends Policies help ensure that Christian Brothers High Nancy Smith-Fagan School adheres to the vision of the Brothers of the Christian Schools and the District Director of Advancement of San Francisco New Orleans. “The Board thanks the families who have entrusted their children to our school,” says Chair David Walrath. “We are constantly amazed by our unbelievable students. They are creative, hardworking and committed to the Lasallian Core Principles. Assisting Connection is a publication of these students are the school’s faculty, staff and administration. -

Acid Mine Drainage in Abandoned Mine

National Conference for Postgraduate Research (NCON -PGR) Acid Mine Drainage in Abandoned Mine Nur Athirah Mohamad Basir Faculty of Chemical and Natural Resources Engineering, Universiti Malaysia Pahang, Kuantan, Pahang, Malaysia Abd Aziz Mohd Azoddein Faculty of Chemical and Natural Resources Engineering, Universiti Malaysia Pahang, Malaysia Kuantan, Pahang, Malaysia Nur Anati Azmi Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universiti Putra Malaysia Abstract-Acid mine drainage (AMD) in abandoned mining operations related oxidation of sulfide mineral affording an acidic solution that contains toxic metal ions. Hence acidic water that flow into the stream had potential health risks to both aquatic life and residents in the vicinity of the mine. Study will be conduct to investigate water quality and AMD characteristics which are pH value of the stream or discharge area, mineral composition in the rock and neutralization value of the rock in AMD mining area. Result shows that pH value of water in Kg. Aur, Chini and Sg. Lembing are acidic with value of 2.81, 4.16 and 3.60 respectively. Maximum concentrations of heavy metals in the study area are: Pb (0.2 mg/L), Cd (0.05 mg/L), Zn (5.1 mg/L), Cu (5.2 mg/L), Mn (10.9 mg/L), Cr (0.2 mg/L), Ni (0.2 mg/L), As (0.005 mg/L) and Fe (202.69 mg/L). Prediction of acid formation using acid-base calculations from all samples shows high potential acid production between 22.84-2500.16 kg CaCO₃/tonne. The ratio of neutralization (NP) with acid potential (APP) shows a very low value (ratio < 1) Sg. -

Political Visions and Historical Scores

Founded in 1944, the Institute for Western Affairs is an interdis- Political visions ciplinary research centre carrying out research in history, political and historical scores science, sociology, and economics. The Institute’s projects are typi- cally related to German studies and international relations, focusing Political transformations on Polish-German and European issues and transatlantic relations. in the European Union by 2025 The Institute’s history and achievements make it one of the most German response to reform important Polish research institution well-known internationally. in the euro area Since the 1990s, the watchwords of research have been Poland– Ger- many – Europe and the main themes are: Crisis or a search for a new formula • political, social, economic and cultural changes in Germany; for the Humboldtian university • international role of the Federal Republic of Germany; The end of the Great War and Stanisław • past, present, and future of Polish-German relations; Hubert’s concept of postliminum • EU international relations (including transatlantic cooperation); American press reports on anti-Jewish • security policy; incidents in reborn Poland • borderlands: social, political and economic issues. The Institute’s research is both interdisciplinary and multidimension- Anthony J. Drexel Biddle on Poland’s al. Its multidimensionality can be seen in published papers and books situation in 1937-1939 on history, analyses of contemporary events, comparative studies, Memoirs Nasza Podróż (Our Journey) and the use of theoretical models to verify research results. by Ewelina Zaleska On the dispute over the status The Institute houses and participates in international research of the camp in occupied Konstantynów projects, symposia and conferences exploring key European questions and cooperates with many universities and academic research centres. -

A Review of Psychosocial and Psychological and Its Related Issues in the Occupational Settings

National Conference for Postgraduate Research (NCON -PGR) A Review of Psychosocial and Psychological and its Related Issues in the Occupational Settings Nuruzzakiyah Bt Mohd Ishanuddin Occupational Safety and Health Program Faculty of Engineering Technology, Universiti Malaysia Pahang 26300, Gambang, Pahang, Malaysia [email protected] Ezrin Hani Bt Sukadarin Occupational Safety and Health Program Faculty of Engineering Technology, Universiti Malaysia Pahang 26300, Gambang Pahang, Malaysia [email protected] Hanida Bt Abdul Aziz Occupational Safety and Health Program Faculty of Engineering Technology, Universiti Malaysia Pahang 26300, Gambang Pahang, Malaysia [email protected] Abstract—Psychosocial risk and psychological risk were different from each other although they were associated to the term of mental health. Both are related to a condition of a person mental health that they are not physically visible specifically in the workplace. The study regarding mental health at the workplace has been conducted long time ago by many researchers, thus psychosocial and psychological issues in the workplace were quite familiar due to the emergence of new types of hazards and associated risks in the workplace settings. In respect to that, no one should be harm by their work nature had driven more studies on these invisible aspects. To avoid more confusion between these terms, proper understanding must be developed in order to use any of these terms in research. This paper draws a clear distinction between these two terms (psychosocial risk and psychological health) and the related issues in the workplace settings. Keywords—Psychosocial risk; psychological health; mental health 1. INTRODUCTION The study on mental health at the workplace was not very prominent among safety and health researchers, this might be due to their nature as the unseen hazards compared to other types of occupational hazards. -

1908 Journal

1 SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES. Monday, October 12, 1908. The court met pursuant to law. Present: The Chief Justice, Mr. Justice Harlan, Mr. Justice Brewer, Mr. Justice White, Mr. Justice Peckham, Mr. Justice McKenna, Mr. Justice Holmes, Mr. Justice Day and Mr. Justice Moody. James A. Fowler of Knoxville, Tenn., Ethel M. Colford of Wash- ington, D. C., Florence A. Colford of Washington, D. C, Charles R. Hemenway of Honolulu, Hawaii, William S. Montgomery of Xew York City, Amos Van Etten of Kingston, N. Y., Robert H. Thompson of Jackson, Miss., William J. Danford of Los Angeles, Cal., Webster Ballinger of Washington, D. C., Oscar A. Trippet of Los Angeles, Cal., John A. Van Arsdale of Buffalo, N. Y., James J. Barbour of Chicago, 111., John Maxey Zane of Chicago, 111., Theodore F. Horstman of Cincinnati, Ohio, Thomas B. Jones of New York City, John W. Brady of Austin, Tex., W. A. Kincaid of Manila, P. I., George H. Whipple of San Francisco, Cal., Charles W. Stapleton of Mew York City, Horace N. Hawkins of Denver, Colo., and William L. Houston of Washington, D. C, were admitted to practice. The Chief Justice announced that all motions noticed for to-day would be heard to-morrow, and that the court would then commence the call of the docket, pursuant to the twenty-sixth rule. Adjourned until to-morrow at 12 o'clock. The day call for Tuesday, October 13, will be as follows: Nos. 92, 209 (and 210), 198, 206, 248 (and 249 and 250), 270 (and 271, 272, 273, 274 and 275), 182, 238 (and 239 and 240), 286 (and 287, 288, 289, 290, 291 and 292) and 167. -

SA Police Gazette 1946

This sampler file contains various sample pages from the product. Sample pages will often include: the title page, an index, and other pages of interest. This sample is fully searchable (read Search Tips) but is not FASTFIND enabled. To view more samplers click here www.gould.com.au www.archivecdbooks.com.au · The widest range of Australian, English, · Over 1600 rare Australian and New Zealand Irish, Scottish and European resources books on fully searchable CD-ROM · 11000 products to help with your research · Over 3000 worldwide · A complete range of Genealogy software · Including: Government and Police 5000 data CDs from numerous countries gazettes, Electoral Rolls, Post Office and Specialist Directories, War records, Regional Subscribe to our weekly email newsletter histories etc. FOLLOW US ON TWITTER AND FACEBOOK www.unlockthepast.com.au · Promoting History, Genealogy and Heritage in Australia and New Zealand · A major events resource · regional and major roadshows, seminars, conferences, expos · A major go-to site for resources www.familyphotobook.com.au · free information and content, www.worldvitalrecords.com.au newsletters and blogs, speaker · Free software download to create biographies, topic details · 50 million Australasian records professional looking personal photo books, · Includes a team of expert speakers, writers, · 1 billion records world wide calendars and more organisations and commercial partners · low subscriptions · FREE content daily and some permanently The resolution of this sampler has been reduced from the original on CD to keep the file smaller for download. South Australian Police Gazette 1946 Ref. AU5103-1946 ISBN: 978 1 921494 85 7 This book was kindly loaned to Archive CD Books Australia by the South Australia Police Historical Society www.sapolicehistory.org Navigating this CD To view the contents of this CD use the bookmarks and Adobe Reader’s forward and back buttons to browse through the pages. -

IOI Corporation Berhad Pukin Grouping Page 2 of 48 Annual Surveillance Assessment (ASA-03) Cum Extension of Scope

IOI Corporation Berhad RSPO Membership No: 2-0002-04-000-00 PLANTATION MANAGEMENT UNIT Pukin Grouping Rompin & Maudzam Shah (Pahang), Segamat & Tangkak (Johor), Malaysia INTERTEK CERTIFICATION INTERNATIONAL SDN BHD (188296-W) Report No.: R2020/10-4 IOI Corporation Berhad Pukin Grouping Page 2 of 48 Annual Surveillance Assessment (ASA-03) cum Extension of Scope ANNUAL SURVEILLANCE ASSESSMENT (ASA-03) cum EXTENSION OF SCOPE ON RSPO CERTIFICATION ASSESSMENT REPORT IOI CORPORATION BERHAD RSPO Membership No: 2-0002-04-000-00 PLANTATION MANAGEMENT UNIT Pukin Grouping Rompin & Maudzam Shah (Pahang), Segamat & Tangkak (Johor), Malaysia Certificate No: RSPO 927888 Issued date: 13 Jun 2012 Expiry date: 12 Jun 2017 Assessment Type Assessment Dates Initial Certification (Main Assessment) 8-11 Dec 2010 Annual Surveillance Assessment (ASA-01) 5-9 Nov 2012 Annual Surveillance Assessment (ASA-02) 22 – 26 Apr 2013 Annual Surveillance Assessment (ASA-03) 08-11 Apr 2014 Annual Surveillance Assessment (ASA-04) Re-Certification Intertek Certification International Sdn Bhd (formerly known as Moody International Certification (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd) 6-L12-01, Level 12, Tower 2, Menara PGRM No. 6 & 8 Jalan Pudu Ulu, Cheras, 56100 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Tel: +00 (603) 9283 9881 Fax: +00 (603) 9284 8187 Email: [email protected] Website: www.intertek.com Intertek RSPO Report: May 2014 INTERTEK CERTIFICATION INTERNATIONAL SDN BHD (188296-W) Report No.: R2020/10-4 IOI Corporation Berhad Pukin Grouping Page 3 of 48 Annual Surveillance Assessment (ASA-03) cum -

Japonisme in Britain - a Source of Inspiration: J

Japonisme in Britain - A Source of Inspiration: J. McN. Whistler, Mortimer Menpes, George Henry, E.A. Hornel and nineteenth century Japan. Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of Art, University of Glasgow. By Ayako Ono vol. 1. © Ayako Ono 2001 ProQuest Number: 13818783 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818783 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 122%'Cop7 I Abstract Japan held a profound fascination for Western artists in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The influence of Japanese art is a phenomenon that is now called Japonisme , and it spread widely throughout Western art. It is quite hard to make a clear definition of Japonisme because of the breadth of the phenomenon, but it could be generally agreed that it is an attempt to understand and adapt the essential qualities of Japanese art. This thesis explores Japanese influences on British Art and will focus on four artists working in Britain: the American James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), the Australian Mortimer Menpes (1855-1938), and two artists from the group known as the Glasgow Boys, George Henry (1858-1934) and Edward Atkinson Hornel (1864-1933). -

Centenary WW1 Victoria Cross Recipients from Overseas

First World War Centenary WW1 Victoria Cross Recipients from Overseas www.1914.org WW1 Victoria Cross Recipients from Overseas - Foreword Foreword The Prime Minister, Rt Hon David Cameron MP The centenary of the First World War will be a truly national moment – a time when we will remember a generation that sacrificed so much for us. Those brave men and boys were not all British. Millions of Australians, Indians, South Africans, Canadians and others joined up and fought with Britain, helping to secure the freedom we enjoy today. It is our duty to remember them all. That is why this programme to honour the overseas winners of the Victoria Cross is so important. Every single name on these plaques represents a story of gallantry, embodying the values of courage, loyalty and compassion that we still hold so dear. By putting these memorials on display in these heroes’ home countries, we are sending out a clear message: that their sacrifice – and their bravery – will never be forgotten. 2 WW1 Victoria Cross Recipients from Overseas - Foreword Foreword FCO Senior Minister of State, Rt Hon Baroness Warsi I am delighted to be leading the commemorations of overseas Victoria Cross recipients from the First World War. It is important to remember this was a truly global war, one which pulled in people from every corner of the earth. Sacrifices were made not only by people in the United Kingdom but by many millions across the world: whether it was the large proportion of Australian men who volunteered to fight in a war far from home, the 1.2 million Indian troops who took part in the war, or the essential support which came from the islands of the West Indies. -

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills As of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills as of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct Supplier Second Refiner First Refinery/Aggregator Information Load Port/ Refinery/Aggregator Address Province/ Direct Supplier Supplier Parent Company Refinery/Aggregator Name Mill Company Name Mill Name Country Latitude Longitude Location Location State AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora Agroaceite Extractora Agroaceite Finca Pensilvania Aldea Los Encuentros, Coatepeque Quetzaltenango. Coatepeque Guatemala 14°33'19.1"N 92°00'20.3"W AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora del Atlantico Guatemala Extractora del Atlantico Extractora del Atlantico km276.5, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Champona, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°35'29.70"N 88°32'40.70"O AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora La Francia Extractora La Francia km. 243, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Buena Vista, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°28'48.42"N 88°48'6.45" O Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - ASOCIACION AGROINDUSTRIAL DE PALMICULTORES DE SABA C.V.Asociacion (ASAPALSA) Agroindustrial de Palmicutores de Saba (ASAPALSA) ALDEA DE ORICA, SABA, COLON Colon HONDURAS 15.54505 -86.180154 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - Cooperativa Agroindustrial de Productores de Palma AceiteraCoopeagropal R.L. (Coopeagropal El Robel R.L.) EL ROBLE, LAUREL, CORREDORES, PUNTARENAS, COSTA RICA Puntarenas Costa Rica 8.4358333 -82.94469444 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - CORPORACIÓN