David Rivett

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part Two ISBN 0 902198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART II K-Z C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

Family Experiments Middle-Class, Professional Families in Australia and New Zealand C

Family Experiments Middle-class, professional families in Australia and New Zealand c. 1880–1920 Family Experiments Middle-class, professional families in Australia and New Zealand c. 1880–1920 SHELLEY RICHARDSON Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Richardson, Shelley, author. Title: Family experiments : middle-class, professional families in Australia and New Zealand c 1880–1920 / Shelley Richardson. ISBN: 9781760460587 (paperback) 9781760460594 (ebook) Series: ANU lives series in biography. Subjects: Middle class families--Australia--Biography. Middle class families--New Zealand--Biography. Immigrant families--Australia--Biography. Immigrant families--New Zealand--Biography. Dewey Number: 306.85092 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. The ANU.Lives Series in Biography is an initiative of the National Centre of Biography at The Australian National University, ncb.anu.edu.au. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Photograph adapted from: flic.kr/p/fkMKbm by Blue Mountains Local Studies. This edition © 2016 ANU Press Contents List of Illustrations . vii List of Abbreviations . ix Acknowledgements . xi Introduction . 1 Section One: Departures 1 . The Family and Mid-Victorian Idealism . 39 2 . The Family and Mid-Victorian Realities . 67 Section Two: Arrival and Establishment 3 . The Academic Evangelists . 93 4 . The Lawyers . 143 Section Three: Marriage and Aspirations: Colonial Families 5 . -

125 Years of Women in Medicine

STRENGTH of MIND 125 Years of Women in Medicine Medical History Museum, University of Melbourne Kathleen Roberts Marjorie Thompson Margaret Ruth Sandland Muriel Denise Sturtevant Mary Jocelyn Gorman Fiona Kathleen Judd Ruth Geraldine Vine Arlene Chan Lilian Mary Johnstone Veda Margaret Chang Marli Ann Watt Jennifer Maree Wheelahan Min-Xia Wang Mary Louise Loughnan Alexandra Sophie Clinch Kate Suzannah Stone Bronwyn Melissa Dunbar King Nicole Claire Robins-Browne Davorka Anna Hemetek MaiAnh Hoang Nguyen Elissa Stafford Trisha Michelle Prentice Elizabeth Anne McCarthy Fay Audrey Elizabeth Williams Stephanie Lorraine Tasker Joyce Ellen Taylor Wendy Anne Hayes Veronika Marie Kirchner Jillian Louise Webster Catherine Seut Yhoke Choong Eva Kipen Sew Kee Chang Merryn Lee Wild Guineva Joan Protheroe Wilson Tamara Gitanjali Weerasinghe Shiau Tween Low Pieta Louise Collins Lin-Lin Su Bee Ngo Lau Katherine Adele Scott Man Yuk Ho Minh Ha Nguyen Alexandra Stanislavsky Sally Lynette Quill Ellisa Ann McFarlane Helen Wodak Julia Taub 1971 Mary Louise Holland Daina Jolanta Kirkland Judith Mary Williams Monica Esther Cooper Sara Kremer Min Li Chong Debra Anne Wilson Anita Estelle Wluka Julie Nayleen Whitehead Helen Maroulis Megan Ann Cooney Jane Rosita Tam Cynthia Siu Wai Lau Christine Sierakowski Ingrid Ruth Horner Gaurie Palnitkar Kate Amanda Stanton Nomathemba Raphaka Sarah Louise McGuinness Mary Elizabeth Xipell Elizabeth Ann Tomlinson Adrienne Ila Elizabeth Anderson Anne Margeret Howard Esther Maria Langenegger Jean Lee Woo Debra Anne Crouch Shanti -

Uma Breve História Da Geometria Molecular Sob a Perspectiva Didático-Epistemológica De Guy Brousseau

Uma Breve História da Geometria Molecular sob a Perspectiva Didático-Epistemológica de Guy Brousseau Kleyfton Soares da Silva Laerte Silva da Fonseca Johnnatan Duarte de Freitas RESUMO O objetivo desta pesquisa foi analisar a evolução histórica da Geometria Molecular (GM), de modo a apresentar discussões, limitações, dificuldades e avanços associados à concepção do saber em jogo e, através disso, contribuir com elementos para análise crítica da organização didática em livros e sequências de ensino. Foi realizado um levantamento histórico na perspectiva epistemológica defendida por Brousseau (1983), em que a compreensão da evolução conceitual do conteúdo visado pelo estudo é alcançada quando há o entrelaçamento de fatos que ajudam a identificar obstáculos que limitaram e/ou limitam a aprendizagem de um dado conteúdo. Trata-se de uma abordagem inédita tanto pelo direcionamento do conteúdo como pela metodologia adotada. A análise histórica permitiu traçar um conjunto de oito obstáculos que por um lado estagnou a evolução do conceito de GM e por outro impulsionou cientistas a buscarem alternativas teóricas e metodológicas para resolver os problemas que foram surgindo ao longo do tempo. O estudo mostrou que a questão da visualização em química e da necessidade de manipulação física de modelos moleculares é constitutiva da própria evolução história da GM. Esse ponto amplifica a necessidade de superação contínua dos obstáculos epistemológicos e cognitivos associados às representações moleculares. Palavras-chave: Análise Epistemológica. Geometria -

Fritz Arndt and His Chemistry Books in the Turkish Language

42 Bull. Hist. Chem., VOLUME 28, Number 1 (2003) FRITZ ARNDT AND HIS CHEMISTRY BOOKS IN THE TURKISH LANGUAGE Lâle Aka Burk, Smith College Fritz Georg Arndt (1885-1969) possibly is best recog- his “other great love, and Brahms unquestionably his nized for his contributions to synthetic methodology. favorite composer (5).” The Arndt-Eistert synthesis, a well-known reaction in After graduating from the Matthias-Claudius Gym- organic chemistry included in many textbooks has been nasium in Wansbek in greater Hamburg, Arndt began used over the years by numerous chemists to prepare his university education in 1903 at the University of carboxylic acids from their lower homologues (1). Per- Geneva, where he studied chemistry and French. Fol- haps less well recognized is Arndt’s pioneering work in lowing the practice at the time of attending several in- the development of resonance theory (2). Arndt also stitutions, he went from Geneva to Freiburg, where he contributed greatly to chemistry in Turkey, where he studied with Ludwig Gattermann and completed his played a leadership role in the modernization of the sci- doctoral examinations. He spent a semester in Berlin ence (3). A detailed commemorative article by W. Walter attending lectures by Emil Fischer and Walther Nernst, and B. Eistert on Arndt’s life and works was published then returned to Freiburg and worked with Johann in German in 1975 (4). Other sources in English on Howitz and received his doctorate, summa cum laude, Fritz Arndt and his contributions to chemistry, specifi- in 1908. Arndt remained for a time in Freiburg as a cally discussions of his work in Turkey, are limited. -

Australian Political Elites and Citizenship Education for `New Australians' 1945-1960

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship Australian Political Elites and Citizenship Education for `New Australians' 1945-1960 Patricia Anne Bernadette Jenkings Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Sydney MAY 2001 In memory of Bill Jenkings, my father, who gave me the courage and inspiration to persevere TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS........................................................................... i ABSTRACT................................................................................................................ iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................. vi ABBREVIATIONS..................................................................................................vii LIST OF TABLES ..................................................................................................viii LIST OF FIGURES................................................................................................. ix INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................... 1 Theoretical Orientation ................................................................................... 9 Methodological Framework.......................................................................... 19 CHAPTER ONE-POLITICAL ELITES, POST-WAR IMMIGRATION AND THE QUESTION OF CITIZENSHIP .... 28 Introduction........................................................................................................ -

Encyclopedia of Women in Medicine.Pdf

Women in Medicine Women in Medicine An Encyclopedia Laura Lynn Windsor Santa Barbara, California Denver, Colorado Oxford, England Copyright © 2002 by Laura Lynn Windsor All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Windsor, Laura Women in medicine: An encyclopedia / Laura Windsor p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1–57607-392-0 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Women in medicine—Encyclopedias. [DNLM: 1. Physicians, Women—Biography. 2. Physicians, Women—Encyclopedias—English. 3. Health Personnel—Biography. 4. Health Personnel—Encyclopedias—English. 5. Medicine—Biography. 6. Medicine—Encyclopedias—English. 7. Women—Biography. 8. Women—Encyclopedias—English. WZ 13 W766e 2002] I. Title. R692 .W545 2002 610' .82 ' 0922—dc21 2002014339 07 06 05 04 03 02 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 ABC-CLIO, Inc. 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper I. Manufactured in the United States of America For Mom Contents Foreword, Nancy W. Dickey, M.D., xi Preface and Acknowledgments, xiii Introduction, xvii Women in Medicine Abbott, Maude Elizabeth Seymour, 1 Blanchfield, Florence Aby, 34 Abouchdid, Edma, 3 Bocchi, Dorothea, 35 Acosta Sison, Honoria, 3 Boivin, Marie -

Bulletin No. 6 Issn 1520-3581

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII LIBRARY THE PACIFIC CIRCLE DECEMBER 2000 BULLETIN NO. 6 ISSN 1520-3581 PACIFIC CIRCLE NEW S .............................................................................2 Forthcoming Meetings.................................................. 2 Recent Meetings..........................................................................................3 Publications..................................................................................................6 New Members...............................................................................................6 IUHPS/DHS NEWS ........................................................................................ 8 PACIFIC WATCH....................................................................... 9 CONFERENCE REPORTS............................................................................9 FUTURE CONFERENCES & CALLS FOR PAPERS........................ 11 PRIZES, GRANTS AND FELLOWSHIPS........................... 13 ARCHIVES AND COLLECTIONS...........................................................15 BOOK AND JOURNAL NEWS................................................................ 15 BOOK REVIEWS..........................................................................................17 Roy M. MacLeod, ed., The ‘Boffins' o f Botany Bay: Radar at the University o f Sydney, 1939-1945, and Science and the Pacific War: Science and Survival in the Pacific, 1939-1945.................................. 17 David W. Forbes, ed., Hawaiian National Bibliography: 1780-1900. -

Contemporary Issues Concerning Scientific Realism

The Future of the Scientific Realism Debate: Contemporary Issues Concerning Scientific Realism Author(s): Curtis Forbes Source: Spontaneous Generations: A Journal for the History and Philosophy of Science, Vol. 9, No. 1 (2018) 1-11. Published by: The University of Toronto DOI: 10.4245/sponge.v9i1. EDITORIALOFFICES Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology Room 316 Victoria College, 91 Charles Street West Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5S 1K7 [email protected] Published online at jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/SpontaneousGenerations ISSN 1913 0465 Founded in 2006, Spontaneous Generations is an online academic journal published by graduate students at the Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology, University of Toronto. There is no subscription or membership fee. Spontaneous Generations provides immediate open access to its content on the principle that making research freely available to the public supports a greater global exchange of knowledge. The Future of the Scientific Realism Debate: Contemporary Issues Concerning Scientific Realism Curtis Forbes* I. Introduction “Philosophy,” Plato’s Socrates said, “begins in wonder” (Theaetetus, 155d). Two and a half millennia later, Alfred North Whitehead saw fit to add: “And, at the end, when philosophical thought has done its best, the wonder remains” (1938, 168). Nevertheless, we tend to no longer wonder about many questions that would have stumped (if not vexed) the ancients: “Why does water expand when it freezes?” “How can one substance change into another?” “What allows the sun to continue to shine so brightly, day after day, while all other sources of light and warmth exhaust their fuel sources at a rate in proportion to their brilliance?” Whitehead’s addendum to Plato was not wrong, however, in the sense that we derive our answers to such questions from the theories, models, and methods of modern science, not the systems, speculations, and arguments of modern philosophy. -

Our Chemical Cultural Heritage Masson and Rivett (1858–1961) PETRONELLA NEL

Our chemical cultural heritage Masson and Rivett (1858–1961) PETRONELLA NEL A new phase for chemistry at the University of Melbourne began in 1886, featuring David Masson and Albert Rivett, who also had instrumental roles in the birth of CSIRO. Organisation (CSIRO). Masson supported Antarctic research for 25 years, beginning with Douglas Mawson’s expedition of 1911. Born and educated in England at the University of Edinburgh, he was a noted lecturer and researcher. After the death of Kirkland in 1885, chemistry became part of the science degree, along with the appointment of Masson as professor in 1886. His research work included the theory of solutions, and the periodic classi8cation of the elements. Much of his research was done in collaboration with talented students such as David Rivett and his own son Irvine Masson. Masson was knighted in 1923. He is commemorated by the Masson Theatre and Masson Road at the University of Melbourne, a mountain range and island in Antarctica, a portrait painting by William McInnes in the foyer of the School of Chem- istry, the Masson lectureship from the Australian National Research Council, and the Masson Memo- Figure 1. David Orme Masson. Photograph by Kricheldorff, c.1920s. UMA/I/1438, University of Melbourne Archives. (Sir) David Orme Masson (1858–1937) Masson was Professor of Chemistry at the University of Melbourne from 1886 to1923. As well as being a teacher and researcher, he contributed to Australian scienti8c and public life. He was instrumental in the establishment and governance of many important bodies including the Council for Scienti8c and Indus- Figure 2. -

Dislocating the Frontier Essaying the Mystique of the Outback

Dislocating the frontier Essaying the mystique of the outback Dislocating the frontier Essaying the mystique of the outback Edited by Deborah Bird Rose and Richard Davis Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Dislocating the frontier : essaying the mystique of the outback. Includes index ISBN 1 920942 36 X ISBN 1 920942 37 8 (online) 1. Frontier and pioneer life - Australia. 2. Australia - Historiography. 3. Australia - History - Philosophy. I. Rose, Deborah Bird. II. Davis, Richard, 1965- . 994.0072 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Indexed by Barry Howarth. Cover design by Brendon McKinley with a photograph by Jeff Carter, ‘Dismounted, Saxby Roundup’, http://nla.gov.au/nla.pic-vn3108448, National Library of Australia. Reproduced by kind permission of the photographer. This edition © 2005 ANU E Press Table of Contents I. Preface, Introduction and Historical Overview ......................................... 1 Preface: Deborah Bird Rose and Richard Davis .................................... iii 1. Introduction: transforming the frontier in contemporary Australia: Richard Davis .................................................................................... 7 2. -

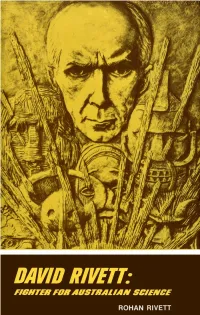

David Rivett: FIGHTER for AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE

DAVID RIVETT: FIGHTER FOR AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE OTHER WORKS OF ROHAN RIVETT Behind Bamboo. 1946 Three Cricket Booklets. 1948-52 The Community and the Migrant. 1957 Australian Citizen: Herbert Brookes 1867-1963. 1966 Australia (The Oxford Modern World Series). 1968 Writing About Australia. 1970 This page intentionally left blank David Rivett as painted by Max Meldrum. This portrait hangs at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation's headquarters in Canberra. ROHAN RIVETT David Rivett: FIGHTER FOR AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE RIVETT First published 1972 All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission © Rohan Rivett, 1972 Printed in Australia at The Dominion Press, North Blackburn, Victoria Registered in Australia for transmission by post as a book Contents Foreword Vll Acknowledgments Xl The Attack 1 Carving the Path 15 Australian at Edwardian Oxford 28 1912 to 1925 54 Launching C.S.I.R. for Australia 81 Interludes Without Playtime 120 The Thirties 126 Through the War-And Afterwards 172 Index 219 v This page intentionally left blank Foreword By Baron Casey of Berwick and of the City of Westminster K.G., P.C., G.C.M.G., C.H., D.S.a., M.C., M.A., F.A.A. The framework and content of David Rivett's life, unusual though it was, can be briefly stated as it was dominated by some simple and most unusual principles. He and I met frequently in the early 1930's and discussed what we were both aiming to do in our respective fields. He was a man of the most rigid integrity and way of life.