Eliminating the Drudge Work”: Campaigning for University- Based Nursing Education in Australia, 1920-1935

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nursing Community Apgar Questionnaire in Rural Australia: an Evidence Based Approach to Recruiting and Retaining Nurses

Boise State University ScholarWorks Nursing Faculty Publications and Presentations School of Nursing 1-1-2017 The ursinN g Community Apgar Questionnaire in Rural Australia: An Evidence Based Approach to Recruiting and Retaining Nurses Molly Prengaman Boise State University Daniel R. Terry University of Melbourne David Schmitz University of North Dakota Ed Baker Boise State University This document was originally published in Online Journal of Rural Nursing and Health Care by Rural Nurse Organization. This work is provided under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 license. Details regarding the use of this work can be found at: http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The Nursing Community Apgar Questionnaire in rural Australia: An evidence based approach to recruiting and retaining nurses Molly Prengaman, PhD, FNP-BC1 Daniel R. Terry, PhD2 David Schmitz, MD3 Ed Baker, PhD4 1 Associate Professor, School of Nursing, Boise State University, [email protected] 2 Research Fellow, Department of Rural Health, University of Melbourne ; Lecturer, School of Nursing, Midwifery and Healthcare, Federation University, [email protected] 3 Professor, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of North Dakota, [email protected] 4 Professor, Center for Health Policy, Boise State University, [email protected] Abstract Purpose: To date, the Nursing Community Apgar Questionnaire (NCAQ) has been effectively utilized to quantify resources and capabilities of a rural Idaho communities to recruit and retain nurses. As such, the NCAQ was used in a rural Australian context to examine its efficacy as an evidence-based tool to better inform nursing recruitment and retention. Sample: The sample included nursing administrators, senior nurses and other nurses from six health facilities who were familiar with the community and knowledgeable with health facility recruitment and retention history. -

The Practice of Registered Nurses in Rural and Remote Areas of Australia: Case Study Research

The practice of Registered Nurses in rural and remote areas of Australia: Case study research Nicola Lisa Whiteing BSc (Hons), MSc (Distinction), PGDip HE, RN, ANP, RNT A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Central Queensland University April 2019 Abstract This study aimed to delineate the roles and responsibilities of Registered Nurses (RNs) working in rural and remote areas of Australia and to explore the clinical and educational preparation required to fulfil such roles and responsibilitie . Whilst much research exists surrounding rural and remote nursing, few studies have looked in depth at the roles and responsibilities and necessary preparation for rural and remote nursing. Indeed, much of the literature encompasses rural and remote nurse data within the wider metropolitan workforce. There is limited research which clearly defines the rural and remote populations being studied. This study, however, clearly delineates those nurses working in rural and remote locations by the Australian Standard Geographical Classification – Remote Areas system (ASGC-RA). It is known that nursing is facing a workforce crisis with many nurses due to retire in the next ten to 15 years. It is also known that this is worse in rural and remote areas in which the average age of the workforce is higher and there are issues with recruitment and retention of nurses. Thus, there is a need to understand the practice of RNs, preparation for the role and challenges that need to be addressed in order that such workforce issues can be addressed. The study was carried out utilising Yin’s case study research design. -

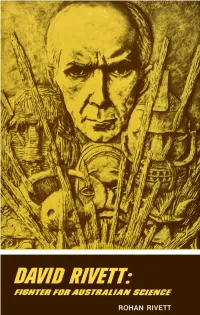

David Rivett

DAVID RIVETT: FIGHTER FOR AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE OTHER WORKS OF ROHAN RIVETT Behind Bamboo. 1946 Three Cricket Booklets. 1948-52 The Community and the Migrant. 1957 Australian Citizen: Herbert Brookes 1867-1963. 1966 Australia (The Oxford Modern World Series). 1968 Writing About Australia. 1970 This page intentionally left blank David Rivett as painted by Max Meldrum. This portrait hangs at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation's headquarters in Canberra. ROHAN RIVETT David Rivett: FIGHTER FOR AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE RIVETT First published 1972 All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission © Rohan Rivett, 1972 Printed in Australia at The Dominion Press, North Blackburn, Victoria Registered in Australia for transmission by post as a book Contents Foreword Vll Acknowledgments Xl The Attack 1 Carving the Path 15 Australian at Edwardian Oxford 28 1912 to 1925 54 Launching C.S.I.R. for Australia 81 Interludes Without Playtime 120 The Thirties 126 Through the War-And Afterwards 172 Index 219 v This page intentionally left blank Foreword By Baron Casey of Berwick and of the City of Westminster K.G., P.C., G.C.M.G., C.H., D.S.a., M.C., M.A., F.A.A. The framework and content of David Rivett's life, unusual though it was, can be briefly stated as it was dominated by some simple and most unusual principles. He and I met frequently in the early 1930's and discussed what we were both aiming to do in our respective fields. He was a man of the most rigid integrity and way of life. -

Vol24.3-5.Pdf

RESEARCH PAPER THE EDUCATIONAL NEEDS OF NURSES WORKING IN AUSTRALIAN GENERAL PRACTICES Tessa Pascoe, MRCNA, RN, RM, BN, B.Community Ed, Former Lyndall Whitecross, MBBS, FRACGP, Grad.Dip Family Medicine, Policy Advisor, Nursing in General Practice Project, Royal GP Advisor, The Royal Australian College of General College of Nursing Australia, Canberra, Australia. Practitioners, South Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. [email protected]. Teri Snowdon, BA(Hons), BSW(Hons) NSW, ARMIT, Ronelle Hutchinson, PhD, BA (Hons), Former Policy Advisor, National Manager Quality Care and Research, The Royal Nursing in General Practice, The Royal Australian College of Australian College of General Practitioners, South Melbourne, General Practitioners, South Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Victoria, Australia. Elizabeth Foley, FRCNA, AFACHSE, RN, Med, Director, Nursing Accepted for publication August 2006 Policy and Strategic Developments, Royal College of Nursing ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Australia, Canberra, Australia. This study was funded by the Australian Government Department of Health Ian Watts, BSW, Dip Soc Plan, MBA (Exec,), National Manager and Ageing. GP Advocacy and Support, The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, South Melbourne, Victoria, and Adjunct Senior Lecturer , Faculty of Medicine , University of Sydney, Australia. Key words: general practice, education, primary care, nursing education ABSTRACT Discussion: The education areas that were rated as important Objective: by a high number of the nurses appeared to relate To describe the educational needs of nurses directly to the activities nurses currently undertake in working in general medical practice in Australia. Australian general practice. Barriers to education may reflect the workforce characteristics of general Design: practice nurses and/or the capacity of general Survey research combining qualitative and practices to finance training for employees. -

Australian Political Elites and Citizenship Education for `New Australians' 1945-1960

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship Australian Political Elites and Citizenship Education for `New Australians' 1945-1960 Patricia Anne Bernadette Jenkings Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Sydney MAY 2001 In memory of Bill Jenkings, my father, who gave me the courage and inspiration to persevere TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS........................................................................... i ABSTRACT................................................................................................................ iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................. vi ABBREVIATIONS..................................................................................................vii LIST OF TABLES ..................................................................................................viii LIST OF FIGURES................................................................................................. ix INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................... 1 Theoretical Orientation ................................................................................... 9 Methodological Framework.......................................................................... 19 CHAPTER ONE-POLITICAL ELITES, POST-WAR IMMIGRATION AND THE QUESTION OF CITIZENSHIP .... 28 Introduction........................................................................................................ -

Nursing in Australia, 1899-1975

.b.qþ Developing an awareness of professionalism: nursing in Australia,'1899 - 1975 Mary Peterson. i Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department i of History of the University of Adelaide. I I I 1995 't March I l I I I I Contents Page Statement I Abstract ii Acknowledgements iv List of illustrations vi Abbreviations viii 1. Introduction 1 2. The establishment of associations 8 3. Wartime rivalry 41, 4. Focus on education 62 5. The concept of professionalism 97 6. The image of the nurse 128 7. Nursing as an occupation for women 148 8. Conclusion lU Bibliography 188 I Statement This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any degree of diploma in any university and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference in made in the text of the thesis. I consent to the thesis being made available for photocopying and loan if accepted for the award of the degree. Mary Peterson l1 Abstract Developing an awareness of professionalism: nursing in Australia,1.899 - 7975 This thesis examines the changing concerns and aspirations of general nurses in Australia from 1899 to 7975. It is shown that the first nurses' associations were developed under doctors' direction; how between the 1920s and World War Two rivalry and hostility developed between the longer established associations and the emerging nurses' unions. The thesis then shows how in the post-war years, nurses' concerns began to focus on the basic education nurses were then receiving. -

Australia Health Care Systems in Transition I IONAL B at an RN K E F T O N R I WORLD BANK

European Observatory on Health Care Systems Australia Health Care Systems in Transition I IONAL B AT AN RN K E F T O N R I WORLD BANK PLVS VLTR R E T C N O E N M S P T R O U L C E T EV ION AND D The European Observatory on Health Care Systems is a partnership between the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, the Government of Greece, the Government of Norway, the Government of Spain, the European Investment Bank, the Open Society Institute, the World Bank, the London School of Economics and Political Science, and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Health Care Systems in Transition Australia 2001 Written by Melissa Hilless and Judith Healy Australia II European Observatory on Health Care Systems AMS 5012667 (AUS) 2001 RESEARCH AND KNOWLEDGE FOR HEALTH By the year 2005, all Member States should have health research, information and communication systems that better support the acquisition, effective utilization, and dissemination of knowledge to support health for all. Keywords DELIVERY OF HEALTH CARE EVALUATION STUDIES FINANCING, HEALTH HEALTH CARE REFORM HEALTH SYSTEM PLANS – organization and administration AUSTRALIA ©European Observatory on Health Care Systems 2001 This document may be freely reviewed or abstracted, but not for commercial purposes. For rights of reproduction, in part or in whole, application should be made to the Secretariat of the European Observatory on Health Care Systems, WHO Regional Office for Europe, Scherfigsvej 8, DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark. The European Observatory on Health Care Systems welcomes such applications. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the European Observatory on Health Care Systems or its participating organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

30 June, 2019 Educating the Nurse of the Future (Secretariat)

30 June, 2019 Educating the Nurse of the Future (Secretariat) 02 6289 9137 [email protected] Dear Reviewers of Nursing Education, Submission to Educating the Nurse of the Future: Independent Review of Nursing Education in Australia. CHA welcomes an independent Review into Nursing Education in Australia, noting that this is the first significant review of education to be conducted in over a decade. CHA is a significant employer of the nursing workforce in Australia, with substantial contributions to nursing education and training. CHA is Australia’s largest non-government grouping of health, community, and aged care services accounting for approximately 10% of hospital-based healthcare in Australia. Our members also provide around 30% of private hospital care, 5% of public hospital care, 12% of aged care facilities, and 20% of home care and support for the elderly. Level 2, Favier House, 51 Cooyong Street, Braddon ACT 2612 PO Box 245, Civic Square ACT 2608 02 6203 2777 www.cha.org.au Catholic Health Australia ABN 30 351 500 103 The nursing workforce is the single largest workforce in Australia, with over 378,325 nurses in 2019, three times as large as the medical practitioner workforce.1 As such, CHA thus recognises that the impacts of a review are likely to be significant and grateful for the opportunity to participate. CHA members report a large variation in work preparedness of newly graduated nurses. Improving this variation necessitates changes be made to enrolment and graduation requirements of nursing students. CHA and its members strongly recommend the introduction of standardisation in enrolment requirements for both domestic and international students entering nursing education. -

A New Era Begins

Edition 129 • April 2017 TheLion Wesley College Community Magazine A new era begins... Features: From Wesley's past to Framing the Future | A long life well lived | New role for our new residence A True Education Contents Editorial Editorial ............................................ 2 I don’t receive a lot of feedback through the mail, but last year I received a letter to which I did not reply at the time, because the issue it Principal's lines ................................. 3 dealt with needs, I think, a public response. In essence, it drew attention to how we select material for this magazine. The letter was not in any way Features antagonistic – in fact, the tone was courteous, respectful and full of goodwill 2016 Scholars and Duces ............ 5 towards what we seek to achieve in this publication – but pointed towards a publishing conundrum I have felt as well. Let me share a few extracts: Academic Excellence 2016 .......... 6 From Wesley's past to While most assuredly the reports of past students who are “high achievers”… Framing the Future ...................... 7 are certainly well merited…these would number possibly 25% of the student body over the many years of Wesley…There appears to be little recognition A long life well lived ..................... 9 attributed to, or acknowledgement of, the greater number who make up the New role for our remaining 75%. new residence ............................. 10 Australia Day honours 2017 ......... 11 These students equally absorbed the “Wesley spirit” (there’s no disputing that) which very clearly encouraged them…From this group came the doctors, solicitors, accountants, all other professions, merchants, farmers, ............... 12 College Snapshots tradesmen etc. -

Download Download

VOLUME 38, ISSUE 1 DEC 2020 – FEB 2021 AUSTRALIAN JOURNAL ISSN 1447–4328 OF ADVANCED NURSING DOI 2020.381 An international peer-reviewed journal of nursing and midwifery research and practice IN THIS ISSUE EDITORIALS Relaunched, the Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing in the year of the Nurse and Midwife. Marnie C and Peters MDJ. P. 1 • 2020.381.411 “Taking our blindfolds off”: acknowledging the vision of First Nations peoples for nursing and midwifery. Sherwood J, West R, Geia L, et al. PP. 2–5 • 2020.381.413 RESEARCH ARTICLES Evaluating the impact of reflective practice groups for nurses in an acute hospital setting. Davey B, Byrne S, Millear P, et al. PP. 6–17 • 2020.381.220 Identifying barriers and facilitators of full service nurse-led early medication abortion provision: qualitative findings from a Delphi study. de Moel-Mandel C, Taket A, Graham M. PP. 18–26 • 2020.381.144 Qualitative determination of occupational risks among operating room nurses. Çelikkalp Ü and Sayılan AA. PP. 27–35 • 2020.381.104 Documenting patient risk and nursing interventions: record audit. Bail K, Merrick E, Bridge C, et al. PP. 36–44 • 2020.381.167 An audit of obesity data and concordance with diagnostic coding for patients admitted to Western Australian Country Health Service hospitals. McClean K, Cross M, Reed S. PP. 45–52 • 2020.381.99 Inpatient falls prevention: state-wide survey to identify variability in Western Australian hospitals. Ferguson C, Mason L, Ho P. PP. 53–59 • 2020.381.296 The Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing is the peer-reviewed scholarly journal of the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation (ANMF). -

Nurses & Midwives in Australian History: a Guide to Historical Sources, Unlock the Past

Nurses, Midwives and Health Professionals includes nurses who served during World Wars Nurses & Midwives in Australian History: a guide to Historical Sources, Unlock the Past, 215 This book written by Professor R Lynette Russell & Noeline Kyle, together with Dr Jennifer Blundell, is an up to date source book for all historians of nursing and midwifery, purchase a copy from here or from gould.com.au The following list of sources was compiled by Noeline Kyle: Adam-Smith, Patsy, Australian Women at War, Nelson, Melbourne, 1984. Adcock, Winifred et al (compilers), With Courage & Devotion: A History of Midwifery in New South Wales, NSW Midwives Association (RANF), Anvil Press, Wamberal, 1984. Armstrong, Dorothy Mary, The First Fifty Years: A History of Nursing at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, from 1882 to 1932, RPA Hospital Graduate Nurses’ Association, 1965. Barlow, Pam, ed The longest mile : a nurse in the Vietnam War, 1968-69 : letters from nursing sister Joan B.F. MacLeod who served in Vietnam as a member of the Royal Australian Army Nursing Corps, Townsville, 2006. Barker, Marianne Nightingales in the mud: the diggers sisters of the Great War, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1989. Bassett, Jan Guns and brooches: Australian Army nursing from the Boer War to the Gulf War, oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1997. Biedermann, Narelle Tears on my pillow: Australian nurses in Vietnam, Random House, Milsons Point, NSW, 2004. Bingham, Stella, Ministering Angels, Osprey Publishing, London, 1979. Brodsky, Isadore, Sydney's nurse crusaders, Old Sydney Free Press, Sydney, 1968. Brookes, Barbara & Thomson eds Jane Unfortunate folk: essays on mental health treatment 1863-1992, University of Otago Press, Dunedin, NZ, 2001. -

International Perspectives on Rural Nursing: Australia, Canada, Usa

Aust. J. Rural Health (2002) 10, 104–111 OriginalBlackwellOxford,1038-5282200210457australianINTERNATIONAL10.1046[sol Australian Blackwell UKAJRThe journalScience, ]j.1038-5282.2002.00457.x Journal Science of Ltd PERSPECTIVESrural of Asia healthRural Pty Health Ltd ON RURAL NURSING: A. BUSHY Article BEES SGML INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES ON RURAL NURSING: AUSTRALIA, CANADA, USA Angeline Bushy University of Central Florida School of Nursing, Daytona Beach, Florida, USA ABSTRACT: This article compares and contrasts nursing practice in rural areas based on selected publications by nurse scholars from Australia, Canada and the USA. By no means is the analysis complete; rather this pre- liminary effort is designed to provoke interest about rural nursing in the global village. The information can be used to examine the rural phenomenon in greater depth from an international perspective and challenges nurses to collaborate, study, develop and refine the foundations of rural practice across nations and cultures. KEY WORDS: international nursing, rural healthcare, rural nursing. INTRODUCTION than urban residents. However, they also tend to seek medical care less often than urban residents. Publications from three countries reveal that nurses Rural communities have fewer people living in larger who practice in rural environments provide services to and more remote geographical regions, which affects individuals and their families (client systems) in a similar economic, political and healthcare delivery systems. The context. Summary articles prepared by nurse scholars more remote the community, the lower the population describe more similarities than differences among rural density tends to be. In other words, rural regions often nurses in Australia,1–3 Canada4,5 and the USA.6–8 Based do not have the critical mass to support public infra- on analysis of select publications, several international structures that are fiscally sound.