Trends in Southeast Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Ally at the Crossroads: Thailand in the US Alliance System Kitti Prasirtsuk

8 An Ally at the Crossroads: Thailand in the US Alliance System Kitti Prasirtsuk In the second decade of the 21st century, the United States is increasingly finding itself in a difficult situation on several fronts. The economic turbulence ushered in by the Subprime Crisis of 2008 led to long-term adverse effects on the US economy. This economic crisis has signified the relative decline of Western supremacy, as the economic difficulties have been lengthy and particularly spread to the Eurozone, the recovery of which is even more delayed than that of the United States. In terms of security, the War on Terror turned out to be a formidable threat, as demonstrated in the form of extremist terrorism wrought under the banner of Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), which is now involving more people and is spreading beyond the Middle East. Europe’s immigrant crisis is also giving the West a headache. The rise of China insists that the United States has to recalibrate its strategy in managing allies and partner countries in East Asia. The ‘pivot’, or rebalancing, towards Asia, as framed under the US administration of Barack Obama since 2011, is a case in point. While tensions originating from the Cold War remain a rationale to keep US alliances intact in North-East Asia, this is less the case in South-East Asia, particularly in Thailand and the Philippines, both of which are traditional US allies. While American troops have remained in both Japan and Korea, they withdrew from the Philippines in 1992. The withdrawal from Thailand happened in 1976 following the end of the Vietnam War. -

The Thickening Web of Asian Security Cooperation: Deepening Defense

The Thickening Web of Asian Security Cooperation Deepening Defense Ties Among U.S. Allies and Partners in the Indo-Pacific Scott W. Harold, Derek Grossman, Brian Harding, Jeffrey W. Hornung, Gregory Poling, Jeffrey Smith, Meagan L. Smith C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR3125 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0333-9 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2019 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover photo by Japan Maritime Self Defense Force. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Since the turn of the century, an important trend toward new or expanded defense cooperation among U.S. -

Thailand: Background and U.S

Thailand: Background and U.S. Relations Emma Chanlett-Avery Specialist in Asian Affairs February 8, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL32593 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Thailand: Background and U.S. Relations Summary U.S.-Thailand relations are of interest to Congress because of Thailand’s status as a long-time military ally and a significant trade and economic partner. However, ties have been complicated by deep political and economic instability in the wake of the September 2006 coup that displaced Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra. After December 2007 parliamentary elections returned many of Thaksin’s supporters to power, the U.S. government lifted the restrictions on aid imposed after the coup and worked to restore bilateral ties. Meanwhile, street demonstrations rocked Bangkok and two prime ministers from Thaksin-aligned parties were forced to step down because of court decisions. A coalition of anti-Thaksin politicians headed by Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva assumed power in December 2008. Bangkok temporarily stabilized, but again erupted into open conflict between the security forces and anti-government protestors in March 2010. By May, the conflict escalated into the worst violence in Bangkok and other cities in decades. Although the government has remained in place, parliamentary elections are required by the end of 2011 and threaten to again spark conflict within a deeply divided society. With this uncertainty, many questions remain on how U.S. relations will fare as Bangkok seeks some degree of political stability. Despite differences on Burma policy and human rights issues, shared economic and security interests have long provided the basis for U.S.-Thai cooperation. -

Deepening Interoperability a Proposal for a Combined Allied Expeditionary Strike Group Within the Indo-Pacific Region by Capt Eli J

IDEAS & ISSUES (CHASE PRIZE ESSAYS) 2019 MajGen Harold W. Chase Prize Essay Contest: First Place Deepening Interoperability A proposal for a combined allied expeditionary strike group within the Indo-Pacific region by Capt Eli J. Morales o restore readiness and en- 40,000 gallons of water from a nearby 1 hance interoperability, co- >Capt Morales is an Instructor at the supply ship. alition partners and allies MAGTF Intelligence Officer Course, Currently, the Navy and Marine Corps in the Indo-Pacific region Marine Detachment, Dam Neck, VA. are faced with a choice to maintain Tmust assemble and deploy an expedi- current levels of forward naval pres- tionary strike group (ESG) built from ence and risk breaking its amphibious the capabilities and resources of each deployment and miss Exercise COBRA force, or reduce its presence and restore coalition partner and ally. The high op- GOLD. On a separate occasion, readiness through adequate training, 2 erational tempo of the last decade has after being ordered to respond to the upgrades, and maintenance. What resulted in deferred maintenance and 2010 Haitian earthquake just one has not changed over the last decade is reduced readiness for Navy and Marine month following a seven month de- the need for Navy and Marine Corps Corps units. In 2012, after the USS ployment, the USS Bataan (LHD-5) units to establish and maintain capable Essex (LHD-2) skipped maintenance suffered a double failure of its evapora- alliances and partnerships within the to satisfy operational requirements, the tors forcing the 22nd MEU to delay Indo-Pacific region. 31st MEU was forced to cut short its rescue operations in order to take on In his farewell letter to the force, former Secretary of Defense James N. -

Exercise Cobra Gold Ends Sentenced Aim/ Involved in Special Opera- Thins Cross Training

r- What in the world are we Navy League awards all-around Marines Page A 1 doing in Asia? itPI Liarora Page A -2 `Bandits' snag another victory Page 13-1 Vol IA, No. 23 Published at MCAS KaneoNe Bay. Also serving 1st MED, Camp H.M. Smith and Marine Barracks, Hawaii. .1iine 14, 1990 Two Marines Exercise Cobra Gold ends sentenced Aim/ involved in special opera- thins cross training. for fraud, Cobra Gold 90, a joint- service exercise involving This year's Cobra Gold mail theft the armed forces of Thai- included an amphibious JrISO land and the United States, landing and joint/com- ended June 1. The exer- bined air and land opera- Two Kaneohe-based Ma- cise, which was conducted tions. rines were sentenced to a in and around Chonburi, total of eight years' con. in Nakhon Ratchasima Civic Action/humanitar- finement and dishonorable (Korat) and in Rayong ian projects that took place discharges resulting from Province, was the ninth in during the exercise involved their court-martial convic- the Cobra Gold series. combined U.S./Thai mobile tions on theft and fraud dental and medical teams. charges. The teams conducted daily For more on clinics in several villages The conviction capped a throughout the operational sear of proceedings and in- Cobra Gold, area. School buildings were vestigations by federal, used for primary health clin- civil and military authori- see page A-3 ics and others will be re- ties regarding a credit fraud ferred to existing civilian scheme involving Cpls health care facilities or the Gloria Sykes and Michael combined U.S./Thai medi- D. -

SAF Concludes Participation in Multinational Exercise Cobra Gold 2020 in Thailand

SAF Concludes Participation in Multinational Exercise Cobra Gold 2020 in Thailand 06 Mar 2020 Representatives from the participating countries at the opening ceremony of Exercise Cobra Gold 2020 The Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) participated in Exercise Cobra Gold from 25 February to 6 March 2020 in Phitsanulok, Thailand. The exercise was co-hosted by the Royal Thai Armed Forces and the United States Indo-Pacific Command (US INDOPACOM). This year marks the SAF's 21st year of participation in the exercise. Exercise Cobra Gold 2020 focused on the coordination of multinational Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) operations. The SAF's Changi Regional HADR Coordination Centre (RHCC) and the US INDOPACOM's Center for Excellence in Disaster Management and Humanitarian Assistance jointly facilitated discussions on the regional HADR architecture and mechanisms for effective and efficient coordination of disaster response. This year's Exercise Cobra Gold also include a command post exercise, a field training exercise, and a cyber exercise. A 55-member SAF contingent, led by Chief Guards Officer Brigadier-General Seet Uei Lim, undertook various roles within the Multinational Combined Task Force, alongside their counterparts from the other participating nations. In addition, a five-member team of combat engineers from the Singapore Army also participated in a multinational Engineer Civic AssistanceProgram to construct a community hall and activity centre for the Ban Krang School, situated in Phitsanulok Province, Thailand. Exercise Cobra Gold is one of the largest multinational exercises in the Asia-Pacific region. In its 39th iteration, the annual exercise promotes friendship, interoperability, and mutual understanding amongst the participating armed forces. -

Southeast Asia Solidifies Antiterrorism Support, Lobbies for Postwar Iraq Reconstruction

U.S.-Southeast Asia Relations: Southeast Asia Solidifies Antiterrorism Support, Lobbies For Postwar Iraq Reconstruction Sheldon W. Simon Political Science Department, Arizona State University The past quarter has witnessed growing antiterrorist cooperation by the core ASEAN states (Philippines, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand) with the United States to apprehend the Bali bombers and others bent on attacking Western interests. Although Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand were reticent about supporting the U.S. war in Iraq because of concern about the political backlash from their own Muslim populations, these states as well as Singapore and the Philippines – openly enthusiastic about Washington’s quick Iraq victory – are looking beyond the war to economic reconstruction opportunities there. American plans to reduce and reposition forces in the Pacific may have a Philippine component if Manila agrees to prepositioning military supplies there. The United States also expressed concern over Indonesia’s military assault on Aceh province, Cambodian violence against Thai residents, and Burma’s crackdown on the pro- democracy opposition. Antiterrorist Cooperation in the Philippines Controversy surrounds the joint Philippine-U.S. Balikatan 03 military exercises undertaken this year in Luzon and still in the planning stages for Mindanao. While the Luzon exercises near the former Clark Air Base went off smoothly, plans for the southern Philippines have yet to be implemented. The United States seemed to want to alter the “terms of reference” for the exercise to a “joint operation” that would take place in the Sulu archipelago, home to the Abu Sayyaf terrorist group against which last year’s Balikatan 02 had also been directed. -

AH200710.Pdf

◀ AD3 Eric Kern observes an aircraft descending from the flight deck to the hangar bay on an aircraft elevator aboard USS Ronald Reagan (CVN 76). Photo by MC3 Kevin S. O’Brien [On the Front Cover] Sailors aboard USS Ronald Reagan (CVN 76) hroughout the year, All Hands tries to showcase the stand at attention as two military veterans are laid to rest in the Pacific Ocean during a burial-at- many ways that Sailors around the globe contribute sea ceremony. ADCS Gilberto Gordils Jr., formerly assigned to Strike Fighter Squadron 115, was one to the well-being of their nation. of the veterans laid to rest during the ceremony. Gordils’ former squadron is currently aboard Ronald T Reagan assigned to Carrier Air Wing 14 where many of the Sailors from the squadron gathered to pay You’ll find Sailors just about anywhere, supporting maritime security, fostering international their last respects. cooperation, providing humanitarian assistance, contributing boots on the ground and participating in a Photo by MC3 Joanna M. Rippee huge range of missions. You’ll find evidence of that right here in our annual “Any Day in the Navy” issue, [On the Back Cover] which is intended to highlight the Navy as seen by Navy photographers and others around the world. We Sailors assigned to USS Hawaii (SSN 776) stand at attention after hoisting the National Ensign and here on the staff of All Hands can’t be everywhere at once, but they are. Commissioning Pennant, placing the ship in active service. Hawaii is the third Virginia-class submarine It’s a challenge to take more than 12,000 photos taken between July 2006 and July 2007, and distill to be commissioned, and the first major U.S. -

Disaster-Mgmt-Ref-Hdbk-Thailand.Pdf

Cover and section photo credits Cover Photo: “Wat Yai Chai Mongkhon, Ayutthaya” (Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya, Thailand) by DavideGorla is licensed under CC BY-2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/66321334@N00/16578276372/in/photolist-4Baas4 Country Overview Section Photo: “Long-tail Boat” (Mueang Krabi, Krabi, Thailand) by Ellen Munro is licensed under CC BY-2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/ellenmunro/4563601426/in/photolist-7XgDHd Disaster Overview Section Photo: “Bang Niang Tsunami Alert Center”, (Thailand) by Electrostatico is licensed under CC BY-2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/electrostatico/321187917/in/photolist-4MJtUH Organizational Structure for DM Section Photo: “Cobra Gold 18: Disaster Relief Rescue Operations” (Chachoengsao, Thailand) by Cpl. Breanna Weisenberger, III Marine Expeditionary Force. February 22, 2018. https://www.dvidshub.net/image/4159865/cobra-gold-18-disaster-relief-rescue-operations Infrastructure Section Photo: “Multicolored Traffic Jam in Bangkok” (Bang Khun Phrom, Bangkok, Thailand) by Christian Haugen is licensed under CC BY-2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/christianhaugen/3344053553/in/photolist-66v9BK Health Section Photo: “Hospital, Boats & Shops along the River” (Bangkok, Thailand) by Kathy is licensed under CC BY-2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/44603071@N00/14175574498/in/photolist-7XA9h6 Women, Peace and Security Section Photo: “Woman in Blue, Floating Market” (Bangkok, Thailand) by Julia Maudlin is licensed under CC BY-2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/juliamaudlin/14915627946/in/photolist-oJ3ux5 Conclusion Section Photo: “Floating Market, Thailand” (Ratchaburi, Thailand) by Russ Bowling, is licensed under CC BY-2.0 https://www.flickr.com/photos/robphoto/2901557255/in/photolist-5qpeTe Appendices Section Photo: “Bangkok, Chinatown” (Samphanthawong Khwaeng, Bangkok) by Chrisgel Ryan Cruz is licensed under CC BY-2.0. -

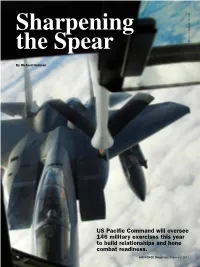

US Pacific Command Will Oversee 146 Military Exercises This Year to Build Relationships and Hone Combat Readiness

Sharpening the Spear USAF photo by SSgt. Lakisha A. Croley By Richard Halloran US Pacific Command will oversee 146 military exercises this year to build relationships and hone combat readiness. 72 AIR FORCE Magazine / February 2011 ar more than any other mili- tary force in the Asia-Pacific region, US Pacific Com- mand trains airmen, soldiers, Fsailors, and marines in an extensive array of exercises intended to give them an advantage over likely adversaries—and thus deter potential enemies. USAF photo TSgt.by Shane CuomoA. Some of the 146 exercises on PA- COM’s schedule for Fiscal 2011 are those of a single service; more focus on joint training. Others are bilateral, where the US seeks to build trust and confidence in the forces of another nation. Still others are multilateral coalition-building efforts. Among the newer type of exercises is training for humanitarian operations. Cobra Gold is representative. In the spring, all four US services are sched- uled to head to Thailand to take part in Cobra Gold alongside Thai forces and those of Singapore, Japan, Indonesia, South Korea, and Malaysia, with a total Left: An F-15 is refueled during December’s Keen Sword exercise at Kadena AB, of 11,000 participants. The US Army Japan. Above: USAF, Thai Air Force, and Singapore Air Force members track a and Marine Corps alternate each year “downed” aircraft during a Cobra Gold exercise. Below: Photographers snap a C-17 Globemaster III during 2010’s RIMPAC exercise. PACOM participates in the most as the US ground element, with the exercises of any military force in the region. -

SAF Participates in Exercise Cobra Gold

SAF Participates in Exercise Cobra Gold 02 May 2005 BAN NONG LOM, TAK, THAILAND (8 May) - Singapore Armed Forces CPT (NS) (DR) Ashim Dutt and Royal Thai Air Force Group Captain Lerpong share their experience during a medical civilian assistance programme (MEDCAP) as part of Exercise Cobra Gold '05. (Courtesy photo) (Released) The Singapore Armed Forces (SAF), together with the Royal Thai Armed Forces, the United States Armed Forces and the Japanese Self Defence Force will be conducting Exercise Cobra Gold from 2 to 13 May 2005 in Chiang Mai, Thailand. The SAF had sent observers to this annual multinational exercise since 1993 and became a full participant in 2000. This year’s exercise will focus on international humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR) operations. The 86-member SAF contingent will be participating in the command post exercise phase of Exercise Cobra Gold, undertaking the role of staff planners for the multinational Combined Task Force alongside their Thai, US, and Japanese counterparts. The SAF delegation will be led by Chief Guards Officer, Brigadier-General Goh Kee Nguan, who is also the Assistant Combined Task Force Commander for the exercise. Observers for this year’s exercise include Australia, Canada, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Sri Lanka, and New Zealand. 1 Exercise Cobra Gold enhances interoperability among the participating armed forces in areas such as joint operational planning processes, as well as command, control and co-ordination issues relating to HADR operations. Apart from enhancing professionalism, the exercise also promotes mutual understanding and friendship. BAN JINGTEENUEAN, Thailand (10 May) - Singapore Army MSG Timothy Rajah examines a local during a Medical Civil Action Program (MEDCAP) visit in support of Exercise Cobra Gold ‘05. -

The Chinese Military's Role in Overseas Humanitarian Assistance

July 11, 2019 The Chinese Military’s Role in Overseas Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief: Contributions and Concerns Author: Matthew Southerland, Policy Analyst, Security and Foreign Affairs Acknowledgments: The author thanks Dennis J. Blasko, Tom Peterman, Jim Welsh, and Jesse Wolfe for their helpful insights and reviews of early drafts. Their assistance does not imply any endorsement of this report’s contents, and any errors should be attributed solely to the author. Disclaimer: This paper is the product of professional research performed by staff of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, and was prepared at the request of the Commission to support its deliberations. Posting of the report to the Commission’s website is intended to promote greater public understanding of the issues addressed by the Commission in its ongoing assessment of U.S.- China economic relations and their implications for U.S. security, as mandated by Public Law 106-398 and Public Law 113-291. However, the public release of this document does not necessarily imply an endorsement by the Commission, any individual Commissioner, or the Commission’s other professional staff, of the views or conclusions expressed in this staff research report. Executive Summary • In recent years, the PLA has increased its involvement in overseas HA/DR missions. Through its contributions to HA/DR, Beijing has provided important assistance to disaster-stricken populations and sought to burnish its image as a “responsible stakeholder” in the international system. • Despite these contributions, Beijing routinely allows political considerations to guide its participation in HA/DR missions, violating the humanitarian spirit of these operations.