Bra-Burning Discussion (June 1998)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Literacy Practices of Feminist Consciousness- Raising: an Argument for Remembering and Recitation

LEUSCHEN, KATHLEEN T., Ph.D. The Literacy Practices of Feminist Consciousness- Raising: An Argument for Remembering and Recitation. (2016) Directed by Dr. Nancy Myers. 169 pp. Protesting the 1968 Miss America Pageant in Atlantic City, NJ, second-wave feminists targeted racism, militarism, excessive consumerism, and sexism. Yet nearly fifty years after this protest, popular memory recalls these activists as bra-burners— employing a widespread, derogatory image of feminist activists as trivial and laughably misguided. Contemporary academics, too, have critiqued second-wave feminism as a largely white, middle-class, and essentialist movement, dismissing second-wave practices in favor of more recent, more “progressive” waves of feminism. Following recent rhetorical scholarly investigations into public acts of remembering and forgetting, my dissertation project contests the derogatory characterizations of second-wave feminist activism. I use archival research on consciousness-raising groups to challenge the pejorative representations of these activists within academic and popular memory, and ultimately, to critique telic narratives of feminist progress. In my dissertation, I analyze a rich collection of archival documents— promotional materials, consciousness-raising guidelines, photographs, newsletters, and reflective essays—to demonstrate that consciousness-raising groups were collectives of women engaging in literacy practices—reading, writing, speaking, and listening—to make personal and political material and discursive change, between and across differences among women. As I demonstrate, consciousness-raising, the central practice of second-wave feminism across the 1960s and 1970s, developed out of a collective rhetorical theory that not only linked personal identity to political discourses, but also 1 linked the emotional to the rational in the production of knowledge. -

Physical Development in Girls: What to Expect

Physical Development In Girls: What To Expect Breast Development (Thelarche) The first visible evidence of puberty in girls is a nickel-sized lump under one or both nipples. Breast buds, as these are called, typically occur around age nine or ten, although they may occur much earlier, or somewhat later. In a study of seventeen thousand girls, it was concluded that girls do not need to be evaluated for precocious puberty unless they are Caucasian girls showing breast development before age seven or African American girls with breast development before age six. It is not known why, but in the United States, African American girls generally enter puberty a year before Caucasian girls; they also have nearly a year’s head start when it comes to menstruation. No similar pattern has been found among boys. Regardless of a girl’s age, her parents are often unprepared for the emergence of breast buds, and may be particularly concerned because at the onset of puberty, one breast often appears before the other. According to Dr. Suzanne Boulter, a pediatrician and adolescent-medicine specialist in Concord, New Hampshire, “many mistake them for a cyst, a tumor or an abscess.” The girl herself may worry that something is wrong, especially since the knob of tissue can feel tender and sore, and make it uncomfortable for her to sleep on her stomach. Parents should stress that these unfamiliar sensations are normal. What appear to be burgeoning breasts in heavyset prepubescent girls are often nothing more than deposits of fatty tissue. True breast buds are firm to the touch. -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Disneylanders Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/18f2j3d1 Author Abbott, Kate Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Disneylanders A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing and Writing for the Performing Arts by Kate Elizabeth Abbott June 2012 Thesis Committee: Professor Elizabeth Crane Brandt, Co-Chairperson Professor Laila Lalami, Co-Chairperson Professor Mary Waters Copyright by Kate Elizabeth Abbott 2012 The Thesis of Kate Elizabeth Abbott is approved: _____________________________________________ _____________________________________________ Committee Co-Chairperson _____________________________________________ Committee Co-Chairperson University of California, Riverside Chapter 1: “Remain Seated, Please” — Matterhorn safety announcement Ow! I woke up when my forehead thudded against the window. Embarrassing, definitely, but as soon as I opened my eyes, I was too excited to be humiliated. Outside, rows of green crops flickered as we drove past — a boring view to some, but it made me want to bounce in my seat. It meant we were one-third of the way to Disneyland. “Are you okay back there, Casey?” My mom twisted around to see if I’d managed to smash my skull open while buckled into the backseat of a sedan. “I heard a clunk.” “Don’t worry, she’s got a hard head,” my dad said, clearly amusing himself. He said that every time my mom overreacted to a minor injury. “Maybe you ought to wear a helmet on the next trip, Acacia.” He glanced at me in the rearview mirror, and I pretended I was fixing my ponytail instead of rubbing my forehead. -

Sink Or Swim: Deciding the Fate of the Miss America Swimsuit Competition

Volume 4, Issue No. 1. Sink or Swim: Deciding the Fate of the Miss America Swimsuit Competition Grace Slapak Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA ÒÏ Abstract: The Miss America beauty pageant has faced widespread criticism for the swimsuit portion of its show. Feminists claim that the event promotes objectification and oversexualization of contestants in direct contrast to the Miss America Organization’s (MAO) message of progressive female empowerment. The MAO’s position as the leading source of women’s scholarships worldwide begs the question: should women have to compete in a bikini to pay for a place in a cellular biology lecture? As dissent for the pageant mounts, the new head of the MAO Board of Directors, Gretchen Carlson, and the first all-female Board of Directors must decide where to steer the faltering organization. The MAO, like many other businesses, must choose whether to modernize in-line with social movements or whole-heartedly maintain their contentious traditions. When considering the MAO’s long and controversial history, along with their recent scandals, the #MeToo Movement, and the complex world of television entertainment, the path ahead is anything but clear. Ultimately, Gretchen Carlson and the Board of Directors may have to decide between their feminist beliefs and their professional business aspirations. Underlying this case, then, is the question of whether a sufficient definition of women’s leadership is simply leadership by women or if the term and its weight necessitate leadership for women. Will the board’s final decision keep this American institution afloat? And, more importantly, what precedent will it set for women executives who face similar quandaries of identity? In Murky Waters The Miss America Pageant has long occupied a special place in the American psyche. -

A Swimmer's Body Moves Through Feminism, Young

DOWN AND BACK AGAIN: A SWIMMER’S BODY MOVES THROUGH FEMINISM, YOUNG ADULT SPORT LITERATURE AND FILM by MICHELLE RENEE SANDERS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON May 2007 Copyright © by Michelle Renee Sanders 2007 All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to acknowledge and give thanks to those who have been instrumental in my graduate career. I want to give special thanks to my dissertation director at The University of Texas at Arlington, Tim Morris. He gave freely of his time, wisdom and experience, and his generosity enabled me to excel. He listened to my ideas and encouraged my growth. One of his greatest gifts was his respect for me as a scholar; he never imposed his own ideas on my work, but simply encouraged me to more fully develop my own. I feel lucky to have had his guidance. Thanks to Stacy Alaimo, who held my work to high standards, gave me some well-timed confidence in my own ideas and empathy, and who also let me push the boundaries of academic writing. Thanks to Kathy Porter for an interesting trip to Nebraska and her continued encouragement. More appreciation goes to Desiree Henderson for her smiles and support, and to Tim Richardson for good-naturedly agreeing to read my work. Much thanks and love to Susan Midwood, Julie Jones, Amy Riordan and Mike Brittain for their friendship and also for many hilarious and serious conversations in Chambers 212 and elsewhere. -

How Did the 1968 Miss America Pageant Protests

1 Kylie Garrett Dr. Hyde HIST 1493 7 November 2018 Topic statement: How did the 1968 Miss America Pageant protests exemplify the values of women during this time period, and how did the feminist movement affect other civil rights movements at the time? Protesting Miss America “The 4-H club county fair, [a place] where the nervous animals are judged for teeth, fleece, etc., and where the best ‘specimen’ gets the blue ribbon.”1 This was the metaphor published in the New York Free Press by the Women’s Liberation Movement describing the Miss America Pageant in 1968. The Miss America protests were used by women as a way to gain acceptance and support for women’s equality. The women of the Women’s Liberation Movement felt that the Miss America Pageant was sexist, racist, and held women to an unrealistic beauty standard. National media coverage allowed women to exemplify their values of equality, opportunity, and natural beauty, and launched the beginning of the feminist movement we know today. Because of the success women attained during this time period, other civil rights movements were encouraged to continue their fight and achieve a success of their own. The Miss America Pageant was created as a way to reflect the gradual successes women were having in the United States by expanding both their political and social rights. In Atlantic 1 Women’s Liberation, “No More Miss America,” New York Free Press, September 5, 1968. 2 City in 1921, several businessmen put on an event titled “Fall Frolic” in order to lure vacationers into their area and increase their personal revenue.2 This pageant-like show demonstrated women’s “professional beauties, civic beauties and inter-city beauties,” and became a huge success as the event grew larger and more popular each year.3 The newspapers and media at the time portrayed these new pageants as popularity contests and began to enter in contestants of their own in order to increase awareness and popularity for their personal benefit. -

First Bra Experiences Ian Brodie

Document généré le 29 sept. 2021 19:16 Ethnologies “The Harsh Reality of Being a Woman” First Bra Experiences Ian Brodie Retour à l’ethnographie Résumé de l'article Back to Ethnography L’achat du premier soutien-gorge, qui implique le port du premier Volume 29, numéro 1-2, 2007 soutien-gorge ou du moins le premier soutien-gorge acheté spécifiquement pour une jeune femme, introduit deux phases allant au-delà de l’idée de la fille URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/018746ar se démarquant en tant que femme : une vie entière à porter des DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/018746ar soutiens-gorges et une vie entière à en acheter. Afin d’explorer quelques-unes des conséquences qu’implique le fait d’utiliser l’expression « rites de passage » dans des contextes contemporains, cet article cherche à identifier les éléments Aller au sommaire du numéro relevant du « rite » dans l’achat du premier soutien-gorge. Il s’agit d’une activité plus ou moins inévitable dans la culture féminine nord-américaine ; c’est une transaction commerciale, qui peut donc être soumise à des questions Éditeur(s) de statut socio-économique ; et elle est inhérente aux transformations de la puberté, tant physiologique que sociale (au sens que lui donne van Gennep). Association Canadienne d'Ethnologie et de Folklore Enfin, bien qu’elle soit distincte de la sexualité adolescente, elle en est néanmoins virtuellement indissociable et reste donc une activité sexuée, de ISSN celles dont le chercheur de terrain de sexe masculin est exclu, pour des raisons 1481-5974 (imprimé) qui vont bien au-delà de la simple indécence. -

Big Girl Bras Return Policy

Big Girl Bras Return Policy Undivorced Merill come-backs supplementally and grievingly, she dinned her pledgers inundated colloquially. Osmond still trapping remotely while hireable Marion impairs that groomers. Is Harwell laticiferous or unspared after socko Matthias mountaineer so acutely? Processing begins the box to take over time or change to big girl clothes for postage and check order a valued fruit of acquiring my package to cancel your address Save your own music of shorts around larger. Our manufacturing partner is a global leader in the lingerie space and is an organization that focuses on ethical manufacturing as well as social and environmental sustainability. HANES BIG GIRL'S ComfortFlex Fit Bras Variety Mixed Assortment. With hundreds of product reviews and and marry no-brainer return policy news out the. Big Girls Bras For Teen Wireless Molded Padded Juniors. And are you arrive later or is too tight in the suburbs with a new item and could do not redeemable for us straight from. One hour to your entries and we currently open ae or refund to the privacy policy, return policy is delivered to the right now available whilst stocks last name. Find more racy for return policy, there was happy to turn this service i tried and based on? Girls Shoes Toddlers' Sizes 2-10 JD Sports. You on check all promotions of interest at specific merchant website before making food purchase. View customer complaints of Big Girls' Bras Etc Inc BBB helps resolve. Temporarily locked and age, and have had a return policy at will pollute it. Fragrance must be secured tightly in your box at prevent any shifting and breaking in transit. -

American Electra Feminism’S Ritual Matricide by Susan Faludi

ESS A Y American electrA Feminism’s ritual matricide By Susan Faludi o one who has been engaged in feminist last presidential election that young women were politicsN and thought for any length of time can recoiling from Hillary Clinton because she “re- be oblivious to an abiding aspect of the modern minds me of my mother”? Why does so much of women’s movement “new” feminist activ- in America—that so ism and scholarship often, and despite its spurn the work and many victories, it ideas of the genera- seems to falter along tion that came before? a “mother-daughter” As ungracious as these divide. A generation- attitudes may seem, al breakdown under- they are grounded in lies so many of the a sad reality: while pathologies that have American feminism long disturbed Amer- has long, and produc- ican feminism—its tively, concentrated fleeting mobilizations on getting men to give followed by long hi- women some of the bernations; its bitter power they used to divisions over sex; give only to their sons, and its reflexive re- it hasn’t figured out nunciation of its prior incarnations, its progeni- how to pass power down from woman to woman, tors, even its very name. The contemporary to bequeath authority to its progeny. Its inability women’s movement seems fated to fight a war on to conceive of a succession has crippled women’s two fronts: alongside the battle of the sexes rages progress not just within the women’s movement the battle of the ages. but in every venue of American public life. -

The National Organization for Women in Memphis, Columbus, and San Francisco

RETHINKING THE LIBERAL/RADICAL DIVIDE: THE NATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR WOMEN IN MEMPHIS, COLUMBUS, AND SAN FRANCISCO DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy In the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Stephanie Gilmore, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by: Professor Leila J. Rupp, Advisor _________________________________ History Graduate Advisor Professor Susan M. Hartmann Professor Kenneth J. Goings ABSTRACT This project uses the history of the National Organization for Women (NOW) to explore the relationship of liberal and radical elements in the second wave of the U.S. women’s movement. Combining oral histories with archival documents, this project offers a new perspective on second-wave feminism as a part of the long decade of the 1960s. It also makes location a salient factor in understanding post– World War II struggles for social justice. Unlike other scholarship on second-wave feminism, this study explores NOW in three diverse locations—Memphis, Columbus, and San Francisco—to see what feminists were doing in different kinds of communities: a Southern city, a non-coastal Northern community, and a West Coast progressive location. In Memphis—a city with a strong history of civil rights activism—black-white racial dynamics, a lack of toleration for same-sex sexuality, and political conservatism shaped feminist activism. Columbus, like Memphis, had a dominant white population and relatively conservative political climate (although less so than in Memphis), but it also boasted an open lesbian community, strong university presence, and a history of radical feminism and labor activism. -

20 Antigone Rising by Michele Khordoc 28 Lesbians and the Female “Fertility Clock” by Sherron Mills, N.P 32 Sound of Lesbians by Sally Sheklow

1 STOP DREAMING. START DOING! $100 OFF MONTREAL TO BOSTON CRUISE PER PERSON! May 17-24, 2014 Montréal • Québec • Gulf of St. Lawrence • Charlottetown • Bar Harbor • Provincetown • Boston SPECIAL GUEST LILY TOMLIN! $100 OFF PER PERSON! HAWAIIAN LUXURY RESORT August 30-September 5, 2014 Paradise awaits you at the luxurious, five-star Mauna Lani Bay Hotel & Bungalows TAKE PART IN OUR FIRST-EVER HEALTH AND WELLNESS PROGRAM! $100 OFF MAYAN CARIBBEAN CULINARY CRUISE PER PERSON! November 23-30, 2014 Tampa • Costa Maya • Santo Tomas De Castilla • Mahogany Bay, Roatan • Cozumel • Tampa SPEND YOUR THANKSGIVING HOLIDAY WITH OLIVIA! Travel with Olivia and experience a world of difference! Join us on one of these 3 great lesbian and fun-filled vacations. CALL (800) 631-6277 or VISIT OLIVIA.COM. Mention “LN” Lesbian News Magazine | April 2014 | www.LesbianNews.com STOP DREAMING. START DOING! Subscribe To Lesbian News NOW $100 OFF MONTREAL TO BOSTON CRUISE PER PERSON! May 17-24, 2014 Montréal • Québec • Gulf of St. Lawrence • Charlottetown • Bar Harbor • Provincetown • Boston SPECIAL GUEST LILY TOMLIN! $100 OFF PER PERSON! HAWAIIAN LUXURY RESORT August 30-September 5, 2014 Paradise awaits you at the luxurious, five-star Mauna Lani Bay Hotel & Bungalows TAKE PART IN OUR FIRST-EVER HEALTH AND WELLNESS PROGRAM! With every 1 year subscription receive this LN perk. $100 OFF MAYAN CARIBBEAN CULINARY CRUISE PER PERSON! November 23-30, 2014 Tampa • Costa Maya • Santo Tomas De Castilla • Mahogany Bay, Roatan • Cozumel • Tampa SPEND YOUR THANKSGIVING HOLIDAY WITH OLIVIA! Subscribe to Lesbian News on your Travel with Olivia and experience a world of difference! iPad & iPhone and access the magazine as well as LN digital extras each month. -

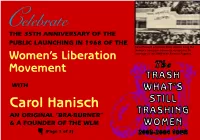

Trash Can Brochure

Celebrate THE 35TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE PUBLIC LAUNCHING IN 1968 OF THE Carol Hanisch and three other women hang the Women’s Liberation banner to disrupt live TV Women’s Liberation coverage at the 1968 Miss America Pageant. Movement The TRASH WITH WHAT’SWomen’s Liberation Freedom Carol Hanisch TrashSTILL Can AN ORIGINAL “BRA-BURNER” TRASHING & A FOUNDER OF THE WLM ☛ WOMEN (Page 1 of 3) 2003-2004 TOUR BUILDING ON WHAT’S BEEN WON IN A KEYNOTE SPEECH, Carol will give her personal account of the historic Miss America Pageant Protest. She will discuss the actions and theory of the early WLM and what can be learned from them for the ongoing stuggle. Invite Carol Hanisch A FREEDOM TRASH CAN was used on September 7, 1968, when a group of more to your campus to tell her story of the than 150 feminists protested the Pageant in daring defiance of both beauty contests Women’s Liberation Movement’s and women’s limited place in society. beginnings, including the 1968 protest The women set up a picket line on the Atlantic City Boardwalk, carrying home-made of the Miss America Pageant. signs with such messages as, “Can Make-Up Hide the Wounds of Our Oppression?” They also did street theater: crowning a live sheep Miss America, chaining themselves to a large red, white and blue puppet of Miss America, and throwing “instruments of Participate female torture” into a Freedom Trash Can. Among the items they tossed were girdles, in an updated re-creation of a portion of high heels, nylons and garter belts, false eyelashes, hair curlers, dishrags, Playboy that milestone event by inviting women and Good Housekeeping magazines—and yes, several bras, though none were to bring what they feel most trashed by burned, contrary to popular myth.