How Did the 1968 Miss America Pageant Protests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Literacy Practices of Feminist Consciousness- Raising: an Argument for Remembering and Recitation

LEUSCHEN, KATHLEEN T., Ph.D. The Literacy Practices of Feminist Consciousness- Raising: An Argument for Remembering and Recitation. (2016) Directed by Dr. Nancy Myers. 169 pp. Protesting the 1968 Miss America Pageant in Atlantic City, NJ, second-wave feminists targeted racism, militarism, excessive consumerism, and sexism. Yet nearly fifty years after this protest, popular memory recalls these activists as bra-burners— employing a widespread, derogatory image of feminist activists as trivial and laughably misguided. Contemporary academics, too, have critiqued second-wave feminism as a largely white, middle-class, and essentialist movement, dismissing second-wave practices in favor of more recent, more “progressive” waves of feminism. Following recent rhetorical scholarly investigations into public acts of remembering and forgetting, my dissertation project contests the derogatory characterizations of second-wave feminist activism. I use archival research on consciousness-raising groups to challenge the pejorative representations of these activists within academic and popular memory, and ultimately, to critique telic narratives of feminist progress. In my dissertation, I analyze a rich collection of archival documents— promotional materials, consciousness-raising guidelines, photographs, newsletters, and reflective essays—to demonstrate that consciousness-raising groups were collectives of women engaging in literacy practices—reading, writing, speaking, and listening—to make personal and political material and discursive change, between and across differences among women. As I demonstrate, consciousness-raising, the central practice of second-wave feminism across the 1960s and 1970s, developed out of a collective rhetorical theory that not only linked personal identity to political discourses, but also 1 linked the emotional to the rational in the production of knowledge. -

The Radical Feminist Manifesto As Generic Appropriation: Gender, Genre, and Second Wave Resistance

Southern Journal of Communication ISSN: 1041-794X (Print) 1930-3203 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsjc20 The radical feminist manifesto as generic appropriation: Gender, genre, and second wave resistance Kimber Charles Pearce To cite this article: Kimber Charles Pearce (1999) The radical feminist manifesto as generic appropriation: Gender, genre, and second wave resistance, Southern Journal of Communication, 64:4, 307-315, DOI: 10.1080/10417949909373145 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10417949909373145 Published online: 01 Apr 2009. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 578 View related articles Citing articles: 4 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsjc20 The Radical Feminist Manifesto as Generic Appropriation: Gender, Genre, And Second Wave Resistance Kimber Charles Pearce n June of 1968, self-styled feminist revolutionary Valerie Solanis discovered herself at the heart of a media spectacle after she shot pop artist Andy Warhol, whom she I accused of plagiarizing her ideas. While incarcerated for the attack, she penned the "S.C.U.M. Manifesto"—"The Society for Cutting Up Men." By doing so, Solanis appropriated the traditionally masculine manifesto genre, which had evolved from sov- ereign proclamations of the 1600s into a form of radical protest of the 1960s. Feminist appropriation of the manifesto genre can be traced as far back as the 1848 Seneca Falls Woman's Rights Convention, at which suffragists Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Coffin Mott, Martha Coffin, and Mary Ann McClintock parodied the Declara- tion of Independence with their "Declaration of Sentiments" (Campbell, 1989). -

Sexual Controversies in the Women's and Lesbian/Gay Liberation Movements

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1985 Politics and pleasures : sexual controversies in the women's and lesbian/gay liberation movements. Lisa J. Orlando University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Orlando, Lisa J., "Politics and pleasures : sexual controversies in the women's and lesbian/gay liberation movements." (1985). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2489. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2489 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POLITICS AND PLEASURES: SEXUAL CONTROVERSIES IN THE WOMEN'S AND LESBIAN/GAY LIBERATION MOVEMENTS A Thesis Presented By LISA J. ORLANDO Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS September 1985 Political Science Department Politics and Pleasures: Sexual Controversies in the Uomen's and Lesbian/Gay Liberation Movements" A MASTERS THESIS by Lisa J. Orlando Approved by: Sheldon Goldman, Member Philosophy \ hi (UV .CVvAj June 21, 19S4 Dean Alfange, Jj' Graduate P ogram Department of Political Science Lisa J. Orlando © 1982, 1983, 1984, 1985 All Rights Reserved iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the following friends who, in long and often difficult discussion, helped me to work through the ideas presented in this thesis: John Levin, Sheila Walsh, Christine Di Stefano, Tom Keenan, Judy Butler, Adela Pinch, Gayle Rubin, Betsy Duren, Ellen Willis, Ellen Cantarow, and Pam Mitchell. -

Shulamith Firestone 1945–2012 2

Shulamith Firestone 1945–2012 2 Photograph courtesy of Lori Hiris. New York, 1997. Memorial for Shulamith Firestone St. Mark’s Church in the Bowery, Parish Hall September 23, 2012 Program 4:00–6:00 pm Laya Firestone Seghi Eileen Myles Kathie Sarachild Jo Freeman Ti-Grace Atkinson Marisa Figueiredo Tributes from: Anne Koedt Peggy Dobbins Bev Grant singing May the Work That I Have Done Speak For Me Kate Millett Linda Klein Roxanne Dunbar Robert Roth 3 Open floor for remembrances Lori Hiris singing Hallelujah Photograph courtesy of Lori Hiris. New York, 1997. Reception 6:00–6:30 4 Shulamith Firestone Achievements & Education Writer: 1997 Published Airless Spaces. Semiotexte Press 1997. 1970–1993 Published The Dialectic of Sex, Wm. Morrow, 1970, Bantam paperback, 1971. – Translated into over a dozen languages, including Japanese. – Reprinted over a dozen times up through Quill trade edition, 1993. – Contributed to numerous anthologies here and abroad. Editor: Edited the first feminist magazine in the U.S.: 1968 Notes from the First Year: Women’s Liberation 1969 Notes from the Second Year: Women’s Liberation 1970 Consulting Editor: Notes from the Third Year: WL Organizer: 1961–3 Activist in early Civil Rights Movement, notably St. Louis c.o.r.e. (Congress on Racial Equality) 1967–70 Founder-member of Women’s Liberation Movement, notably New York Radical Women, Redstockings, and New York Radical Feminists. Visual Artist: 1978–80 As an artist for the Cultural Council Foundation’s c.e.t.a. Artists’ Project (the first government funded arts project since w.p.a.): – Taught art workshops at Arthur Kill State Prison For Men – Designed and executed solo-outdoor mural on the Lower East Side for City Arts Workshop – As artist-in-residence at Tompkins Square branch of the New York Public Library, developed visual history of the East Village in a historical mural project. -

Susan Faludi How Shulamith Firestone Shaped Feminism The

AMERICAN CHRONICLES DEATH OF A REVOLUTIONARY Shulamith Firestone helped to create a new society. But she couldn’t live in it. by Susan Faludi APRIL 15, 2013 Print More Share Close Reddit Linked In Email StumbleUpon hen Shulamith Firestone’s body was found Wlate last August, in her studio apartment on the fifth floor of a tenement walkup on East Tenth Street, she had been dead for some days. She was sixtyseven, and she had battled schizophrenia for decades, surviving on public assistance. There was no food in the apartment, and one theory is that Firestone starved, though no autopsy was conducted, by preference of her Orthodox Jewish family. Such a solitary demise would have been unimaginable to anyone who knew Firestone in the late nineteensixties, when she was at the epicenter of the radicalfeminist movement, Firestone, top left, in 1970, at the beach, surrounded by some of the same women who, a reading “The Second Sex”; center left, with month after her death, gathered in St. Mark’s Gloria Steinem, in 2000; and bottom right, Church IntheBowery, to pay their respects. in 1997. Best known for her writings, Firestone also launched the first major The memorial service verged on radical radicalfeminist groups in the country, feminist revival. Women distributed flyers on which made headlines in the late nineteen consciousnessraising, and displayed copies of sixties and early seventies with confrontational protests and street theatre. texts published by the Redstockings, a New York group that Firestone cofounded. The WBAI radio host Fran Luck called for the Tenth Street studio to be named the Shulamith Firestone Memorial Apartment, and rented “in perpetuity” to “an older and meaningful feminist.” Kathie Sarachild, who had pioneered consciousnessraising and coined the slogan “Sisterhood Is Powerful,” in 1968, proposed convening a Shulamith Firestone Women’s Liberation Memorial Conference on What Is to Be Done. -

GOV 1029 Feminist Political Thought

GOV 1029 Feminist Political Thought Tuesday, Thursday 12-1.15 Fall Semester 2018 Professor Katrina Forrester Office Hours: Tuesday, Thursday 2-3 Office: CGIS K437 E-mail: [email protected] Teaching Fellow: Leah Downey E-mail: [email protected] Course Description: What is feminism? What is patriarchy? What and who is a woman? How does gender relate to sexuality, and to class and race? Should housework be waged, should sex be for sale, and should feminists trust the state? This course is an introduction to feminist political thought since the mid-twentieth century. It introduces students to classic texts of late twentieth-century feminism, explores the key arguments that have preoccupied radical, socialist, liberal, Black, postcolonial and queer feminists, examines how these arguments have changed over time, and asks how debates about equality, work, and identity matter today. We will proceed chronologically, reading texts mostly written during feminism’s so-called ‘second wave’, by a range of influential thinkers including Simone de Beauvoir, Shulamith Firestone, bell hooks and Catharine MacKinnon. We will examine how feminists theorized patriarchy, capitalism, labor, property and the state; the relationship of claims of sex, gender, race, and class; the development of contemporary ideas about sexuality, identity, and gender; and how and whether these ideas change how fundamental problems in political theory are understood. 1 Course Requirements: Participation (25%) includes (a) active participation in discussion (15%); and (b) weekly responses: each week you will send 2-3 brief questions/ comments about the reading to your TF by 5pm the day before section (10%) Paper 1 (25%) 5-6 pages due October 18 4pm. -

Sink Or Swim: Deciding the Fate of the Miss America Swimsuit Competition

Volume 4, Issue No. 1. Sink or Swim: Deciding the Fate of the Miss America Swimsuit Competition Grace Slapak Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA ÒÏ Abstract: The Miss America beauty pageant has faced widespread criticism for the swimsuit portion of its show. Feminists claim that the event promotes objectification and oversexualization of contestants in direct contrast to the Miss America Organization’s (MAO) message of progressive female empowerment. The MAO’s position as the leading source of women’s scholarships worldwide begs the question: should women have to compete in a bikini to pay for a place in a cellular biology lecture? As dissent for the pageant mounts, the new head of the MAO Board of Directors, Gretchen Carlson, and the first all-female Board of Directors must decide where to steer the faltering organization. The MAO, like many other businesses, must choose whether to modernize in-line with social movements or whole-heartedly maintain their contentious traditions. When considering the MAO’s long and controversial history, along with their recent scandals, the #MeToo Movement, and the complex world of television entertainment, the path ahead is anything but clear. Ultimately, Gretchen Carlson and the Board of Directors may have to decide between their feminist beliefs and their professional business aspirations. Underlying this case, then, is the question of whether a sufficient definition of women’s leadership is simply leadership by women or if the term and its weight necessitate leadership for women. Will the board’s final decision keep this American institution afloat? And, more importantly, what precedent will it set for women executives who face similar quandaries of identity? In Murky Waters The Miss America Pageant has long occupied a special place in the American psyche. -

Women's Liberation: Seeing the Revolution Clearly

Sara M. EvanS Women’s Liberation: Seeing the Revolution Clearly Approximately fifty members of the five Chicago radical women’s groups met on Saturday, May 18, 1968, to hold a citywide conference. The main purposes of the conference were to create and strengthen ties among groups and individuals, to generate a heightened sense of common history and purpose, and to provoke imaginative pro- grammatic ideas and plans. In other words, the conference was an early step in the process of movement building. —Voice of Women’s Liberation Movement, June 19681 EvEry account of thE rE-EmErgEncE of feminism in the United States in the late twentieth century notes the ferment that took place in 1967 and 1968. The five groups meeting in Chicago in May 1968 had, for instance, flowered from what had been a single Chicago group just a year before. By the time of the conference in 1968, activists who used the term “women’s liberation” understood themselves to be building a movement. Embedded in national networks of student, civil rights, and antiwar movements, these activists were aware that sister women’s liber- ation groups were rapidly forming across the country. Yet despite some 1. Sarah Boyte (now Sara M. Evans, the author of this article), “from Chicago,” Voice of the Women’s Liberation Movement, June 1968, p. 7. I am grateful to Elizabeth Faue for serendipitously sending this document from the first newsletter of the women’s liberation movement created by Jo Freeman. 138 Feminist Studies 41, no. 1. © 2015 by Feminist Studies, Inc. Sara M. Evans 139 early work, including my own, the particular formation calling itself the women’s liberation movement has not been the focus of most scholar- ship on late twentieth-century feminism. -

In 1968 Feminists Targeted the Miss America Pageant for Protest. They

People & Events: The 1968 Protest In 1968 feminists targeted the Miss America Pageant for protest. They staged a theatrical demonstration outside of the Atlantic City Convention Center on the day of the pageant. The protest was one of the first media events to bring national attention to the emerging Women's Liberation Movement. Over the next decade, the women's movement would rival the civil rights movement in the success it would achieve in a short period of time. 1968 was a year of great upheaval in the United States. It was a year of shocking events, including the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy. The country also was in the midst of the Vietnam War , which caused great internal division in the country. The violent antiwar demonstrations at the Chicago Democratic National Convention that year offered evidence of how divided the country was. The pageant protest was organized by the New York Radical Women (N.Y.R.W.), a group of women who had been active in the civil rights, the New Left, and the antiwar movements. Their experiences in those movements had offered them conflicting messages. As organizers and civil rights activists they were dedicated to working for freedom, yet these organizations were also plagued with their own sexism towards women. Women volunteers, for example, who came to work in the South during the Freedom Summer voter registration project in 1964, were automatically expected to cook and clean in the houses where volunteers lived. Among the first groups to press for a separate women's rights movement was the N.Y.R.W. -

American Electra Feminism’S Ritual Matricide by Susan Faludi

ESS A Y American electrA Feminism’s ritual matricide By Susan Faludi o one who has been engaged in feminist last presidential election that young women were politicsN and thought for any length of time can recoiling from Hillary Clinton because she “re- be oblivious to an abiding aspect of the modern minds me of my mother”? Why does so much of women’s movement “new” feminist activ- in America—that so ism and scholarship often, and despite its spurn the work and many victories, it ideas of the genera- seems to falter along tion that came before? a “mother-daughter” As ungracious as these divide. A generation- attitudes may seem, al breakdown under- they are grounded in lies so many of the a sad reality: while pathologies that have American feminism long disturbed Amer- has long, and produc- ican feminism—its tively, concentrated fleeting mobilizations on getting men to give followed by long hi- women some of the bernations; its bitter power they used to divisions over sex; give only to their sons, and its reflexive re- it hasn’t figured out nunciation of its prior incarnations, its progeni- how to pass power down from woman to woman, tors, even its very name. The contemporary to bequeath authority to its progeny. Its inability women’s movement seems fated to fight a war on to conceive of a succession has crippled women’s two fronts: alongside the battle of the sexes rages progress not just within the women’s movement the battle of the ages. but in every venue of American public life. -

The National Organization for Women in Memphis, Columbus, and San Francisco

RETHINKING THE LIBERAL/RADICAL DIVIDE: THE NATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR WOMEN IN MEMPHIS, COLUMBUS, AND SAN FRANCISCO DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy In the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Stephanie Gilmore, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by: Professor Leila J. Rupp, Advisor _________________________________ History Graduate Advisor Professor Susan M. Hartmann Professor Kenneth J. Goings ABSTRACT This project uses the history of the National Organization for Women (NOW) to explore the relationship of liberal and radical elements in the second wave of the U.S. women’s movement. Combining oral histories with archival documents, this project offers a new perspective on second-wave feminism as a part of the long decade of the 1960s. It also makes location a salient factor in understanding post– World War II struggles for social justice. Unlike other scholarship on second-wave feminism, this study explores NOW in three diverse locations—Memphis, Columbus, and San Francisco—to see what feminists were doing in different kinds of communities: a Southern city, a non-coastal Northern community, and a West Coast progressive location. In Memphis—a city with a strong history of civil rights activism—black-white racial dynamics, a lack of toleration for same-sex sexuality, and political conservatism shaped feminist activism. Columbus, like Memphis, had a dominant white population and relatively conservative political climate (although less so than in Memphis), but it also boasted an open lesbian community, strong university presence, and a history of radical feminism and labor activism. -

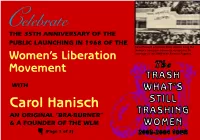

Trash Can Brochure

Celebrate THE 35TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE PUBLIC LAUNCHING IN 1968 OF THE Carol Hanisch and three other women hang the Women’s Liberation banner to disrupt live TV Women’s Liberation coverage at the 1968 Miss America Pageant. Movement The TRASH WITH WHAT’SWomen’s Liberation Freedom Carol Hanisch TrashSTILL Can AN ORIGINAL “BRA-BURNER” TRASHING & A FOUNDER OF THE WLM ☛ WOMEN (Page 1 of 3) 2003-2004 TOUR BUILDING ON WHAT’S BEEN WON IN A KEYNOTE SPEECH, Carol will give her personal account of the historic Miss America Pageant Protest. She will discuss the actions and theory of the early WLM and what can be learned from them for the ongoing stuggle. Invite Carol Hanisch A FREEDOM TRASH CAN was used on September 7, 1968, when a group of more to your campus to tell her story of the than 150 feminists protested the Pageant in daring defiance of both beauty contests Women’s Liberation Movement’s and women’s limited place in society. beginnings, including the 1968 protest The women set up a picket line on the Atlantic City Boardwalk, carrying home-made of the Miss America Pageant. signs with such messages as, “Can Make-Up Hide the Wounds of Our Oppression?” They also did street theater: crowning a live sheep Miss America, chaining themselves to a large red, white and blue puppet of Miss America, and throwing “instruments of Participate female torture” into a Freedom Trash Can. Among the items they tossed were girdles, in an updated re-creation of a portion of high heels, nylons and garter belts, false eyelashes, hair curlers, dishrags, Playboy that milestone event by inviting women and Good Housekeeping magazines—and yes, several bras, though none were to bring what they feel most trashed by burned, contrary to popular myth.