Repor T Resumes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origins and Application of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Origins and Application of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 We the people of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America. — Preamble to the Constitution of the United States of America This preamble sets forth goals for the United States. But when? After adoption of the Constitution, nearly 100 years passed before emancipation, and that involved a civil war. It was more than two generations after that before women were allowed to vote. Our history is replete with discrimination on the basis of race, ethnicity, religion, and gender. Historically, many societies have survived with homogeneity of race, ethnicity, or religion, but never with homogeneity of gender. Because of this one might expect gender based discrimination to be among the first to fall in a democratic society, rather than one of the last. And yet, the 200 year history of our high court boasts of only two female justices. Only a small percentage of the Congress are female and there has never been a female president or vice- president. England has had its Margaret Thatcher, Israel its Golda Meir, and India its Indra Ghandi. The American Democracy has certainly missed the opportunity to lead the world in gender equality in leadership, and without that how can we expect to see gender equality in society? There will never be complete equality until women themselves help to make the laws and elect lawmakers. -

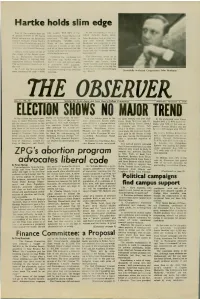

ELECTION SHOWS NO MAJOR TREND Duffy of Connecticut

Hartke holds slim edge Two of the contests that are vote margin. With 80% of the In the 3rd district of Inc.ia ta of special interest to the Notre vote reported, Vance Hartke had which includes South Bend, Dame campus are the Senatorial received 772,000 votes to John Brademas won an easy vic election between Vance Hartke Roudebushes 768,000 votes. tory over Donald Newman. and Richard Roudebush and the None of the networks had Brademas was projected to win Congressional race between John projected a winner at this lime by approximately 20,000 votes. Brademas and Donald Newman. and all of them believed that the This area is traditionally demo cratic and the Brademas victory Indiana is the scene of one of winner could not be declared un was expected. the closest of the Senate races. til the early morning. In it, Democratic incumbent Evidently the candidates lelt The Democrats swept all of Vance Hartke is battling Rep the same way Hirtke went to St. Joseph County. Among the resentative Richard Roudebush. bed at 1 a.m. and will not make casualties was former Notre The vote promises to go down to a statement until morning. Dame security chief Elmer Sokol the wire. Roudebush announced that he who was defeated in his bid for At 2 a.m. the two candidates re-election to the office of Coun will have nothing to say until the Sucessfully re-elected Congressman John Brademas were separated by only a 4000 morning. ty Sheriff. Vol. V., No. 40 THE Serving the Notre Dame and Saint Mary's College CommunityOBSERWednesday, November 4, 1970 ELECTION SHOWS NO MAJOR TREND Duffy of Connecticut. -

The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party

, THE MISSISSIPPI· FREEDOM DEMOCRATIC PARTY Background InformaUon for SUppoMlve CampaIgns by Campus Groups repal"ed by STEV E MAX PolItical Education Project, Room 3091' 119 FIfth Ave., N .. Y.C. Associated with Students for a Democrattc Society THE MISSISSIPPI FREEDOM DEMOCRATIC PARTY: BACKGROUND AND RECENT DEVELOPMENTS by STEVE llJAX The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party was founded April 26, 1964 in order to create an opportunity for meaningful political expres sion for the 438,000 adult Negro Mississippians who traditionally have been denied this right. In addition to being a political instrument, the FDP provides a focus for the coordination of civil rights activity in the state and around the country. Although its memters do not necessarily think in these -terms, the MFDP is the organization above all others whose work is most directly forcing a realignment within the Democratic Party. All individuals and organizations who understand that ' when the Negro is not free, then all are in chains; who realize that the present system of discrimi nation precludes the abolition of poverty, and who have an interest in the destruction of the Dixiecrat-Republican alliance and the purging of the racists from the Democratic Party are potential allies of the MFDP. BACKGROUND INFORMATION The Mississippi Democratic Party runs the state of MisSissippi .with an iron hand. It controls the legislative, executive and judicial be nches of the state government. Prior to the November, 1964 elec tion all 49 state 3enators and all but one of the 122 Representa tives were Democrats. Mississippi sent four Democrats and one Goldwater Republican to Congress last November. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E 133 HON

January 19, 1995 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð Extensions of Remarks E 133 United States. Participants are expected to as- and gas income is shared under the terms of States as a whole. This is a critical problem in sist in planning topical meetings in Washing- ANCSA section 7(i). my home county of El Paso. The rate of ton, and are encouraged to host one or two Mr. Speaker, a version of this bill has been amebiasis, a parasitic infestation, is three staff people in their Member's district over the considered and passed the House in 1992. times higher along the border than in the rest Fourth of July, or to arrange for such a visit to Another version was approved by the Senate of the United States and the rate of another Member's district. Energy and Natural Resources Committee in shigellosis, a bacterial infection, is two times Participants will be selected by a committee 1994. But we have never been able to get the higher. These diseases don't check with immi- composed of U.S. Information Agency [USIA] bill all the way through the process. I hope to gration or customs inspectors for either coun- personnel and past participants of the ex- change that this year. try before crossing borders, nor do they re- change. I have made a few changes in the bill which main at the border. Once these diseases are Senators and Representatives who would I am introducing today. The major change is to in the United States they become a public like a member of their staff to apply for partici- delete the wilderness designations which have health problem for the entire country. -

Ford Congressional Papers: Films/Video, 1946-1973

Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum 1000 Beal Avenue, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2114 www.fordlibrarymuseum.gov Gerald R. Ford Congressional Papers: Films/Video, 1946-1973 Series Descriptions Videotape, 1972 (30 minutes) The series consists of one 3/4" video cassette. The tape is a compilation of four separate programs originally recorded in 1972 on 2" tape. The House of Representatives film office produced three of the programs while the fourth came from WKZO-TV, Kalamazoo, Michigan. The programs are arranged chronologically with the exception of the last, which is undated. Motion Picture Films, 1946-1972 (196 reels) The series contains 196 reels of 16mm film, comprising nearly 55,000 feet. The majority are black and white with sound. Only 19 reels (8,300 feet) are in color. The films include Ford's reports to constituents, some of his campaign commercials, and documentaries relating to Space and Military programs. Among the subjects covered in Ford's "Reports from Washington" are discussions on legislation to alter the Social Security Act, create a G.I. Bill for Korean War veterans, provide appropriations for the construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway, and revise the Internal Revenue Code. Other titles deal with the Korean War, Chinese Communist aggression in Southeast Asia, U.S. intervention in Cuba, the efforts of the Justice Department and the Immigration and Naturalization Service to remove subversives from the United States, and Defense Appropriations. The documentaries include subjects such as "Operation Ivy," the first above ground test of the hydrogen bomb; "Countdown to Polaris," and several NASA films on the Gemini and Apollo Space Programs. -

The Republican Right Since 1945

University of Kentucky UKnowledge American Politics Political Science 1983 The Republican Right since 1945 David W. Reinhard Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Reinhard, David W., "The Republican Right since 1945" (1983). American Politics. 24. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_political_science_american_politics/24 Right SINCE 1945 David W. Reinhard THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Coypright© 1983 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine College, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Club, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of louisville, and Western Kentucky University. Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40506-0024 ISBN: 978-0-8131-5449-7 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Reinhard, David W., 1952- The Republican Right since 1945. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Republican Party (U.S.) 2. Conservatism-United States-Histoty-20th century. 3. United States-Politics and government-1945- I. Title. JK2356.R28 1983 324.2734 82-40460 Contents Preface v 1. If Roosevelt Lives Forever 1 2. A Titanic Ballot-Box Uprising 15 3. The Philadelphia Story 37 4. ANewSetofGuts 54 5. If the Elephant Remembers 75 6. -

UNIONS and the MAKING of the MODERATE REPUBLICAN PARTY in NASSAU COUNTY, NEW YORK by LILLIAN DUDKIEWICZ-CLAYM

LIFE OF THE PARTY: UNIONS AND THE MAKING OF THE MODERATE REPUBLICAN PARTY IN NASSAU COUNTY, NEW YORK By LILLIAN DUDKIEWICZ-CLAYMAN A dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History Written under the direction of Dorothy Sue Cobble And approved by _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey JANUARY, 2019 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Life of the Party: Unions and the Making of the Moderate Republican Party in Nassau County, New York By LILLIAN DUDKIEWICZ-CLAYMAN Dissertation Director: Dorothy Sue Cobble Since county incorporation in 1899, the Nassau County Republican Party has identified with the moderate wing of the party. A key component of its moderate views lies in its support of workers and organized labor. This dissertation describes the evolution of the partnership between organized labor and the Nassau Republican Party and shows how organized labor contributed to the emergence of a strong political Republican machine. Support for organized labor became necessary to the survival and success of the Nassau County Republicans. At the same time, I argue, organized labor thrived in Nassau County in part because of its partnership with moderate Republicans. This mutually beneficial interaction continued into the twenty-first century, maintaining the Nassau County Republican Party as moderates even as the national GOP has moved to the extreme right. Historians and scholars have studied the history of the Nassau County Republican Party and its rise as a powerful political machine. -

Can Big Government Be Rolled Back? by Michael Barone

CAN BIG GOVERNMENT BE ROLLED BACK? BY MICHAEL BARONE AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE CAN BIG GOVERNMENT BE ROLLED BACK? BY MICHAEL BARONE December 2012 AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE Contents Acknowledgments . .iv Introduction . .1 1. The 1920s Republicans . .3 2. 1938 to 1946: The Conservative Coalition . .9 3. Reacting to Roosevelt: The 80th Congress and Beyond . .17 4. 1966 and 1968: Policy Changes at the Margins . .23 5. Achievements and Compromise in the Reagan Era . .29 6. Major Conservative Policy Advances . .35 Conclusion . .43 Notes . .45 About the Author . .49 iii Acknowledgments I wish to thank Samuel Sprunk, who provided sterling research on this project; Karlyn Bowman, who provided sage counsel and advice; Claude Aubert, who designed the cover and layout; and Christy Sadler, who led the editing process. iv Introduction t is a rare proposition on which liberals and conser- and price controls; rationing of materials and food; Ivatives agree: American history over the last hun- and, in World War I, subsidies for farmers to ensure dred years has been a story of the growth of the size food supplies for famine-threatened allies. Such poli- and powers of government. This growth has not been cies produced demands for continued government steady. Conservatives, with some bitterness, have controls and subsidies in the postwar years, not least embraced a theory of ratchets: in every generation, lib- from military veterans who were drafted into service. erals succeed in ratcheting up the size of government But war is not the only friend of the state. Defense and conservatives fail to significantly reduce it. spending even during the Iraq and Afghanistan con- Liberal historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. -

Lawrence F. O'brien Oral History Interview VIII, 4/8/86, by Michael L

LYNDON BAINES JOHNSON LIBRARY ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION The LBJ Library Oral History Collection is composed primarily of interviews conducted for the Library by the University of Texas Oral History Project and the LBJ Library Oral History Project. In addition, some interviews were done for the Library under the auspices of the National Archives and the White House during the Johnson administration. Some of the Library's many oral history transcripts are available on the INTERNET. Individuals whose interviews appear on the INTERNET may have other interviews available on paper at the LBJ Library. Transcripts of oral history interviews may be consulted at the Library or lending copies may be borrowed by writing to the Interlibrary Loan Archivist, LBJ Library, 2313 Red River Street, Austin, Texas, 78705. LAWRENCE F. O'BRIEN ORAL HISTORY, INTERVIEW VIII PREFERRED CITATION For Internet Copy: Transcript, Lawrence F. O'Brien Oral History Interview VIII, 4/8/86, by Michael L. Gillette, Internet Copy, LBJ Library. For Electronic Copy on Diskette from the LBJ Library: Transcript, Lawrence F. O'Brien Oral History Interview VIII, 4/8/86, by Michael L. Gillette, Electronic Copy, LBJ Library. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION LYNDON BAINES JOHNSON LIBRARY AND JOHN FITZGERALD KENNEDY LIBRARY Legal Agreement Pertaining to the Oral History Interview of Lawrence F. O'Brien In accordance with the provisions of Chapter 21 of Title 44, United States Code, and subject to the terms and conditions hereinafter set forth, I, Lawrence F. O'Brien of New -

Continuing Ed. Dept. Has New Director

VOL. NO. 8 Continuing Ed. Dept. Professor Has New Director Publishes The results of Dr. Thomas Laudelina Martinez of registration. This spring our Ruth’s research on the atomic Bronxville, New York, has been enrollment in part time students nucleus and its structural named Director of Continuing is 248 over that of a year ago. models has recently been ac Education and assistant dean, At the same time we are cepted for publication in the which became effective pleased that Miss Martinez will Physical Review. An assistant February 18. be our first woman dean.” professor of chemistry at SHU, Dean Martinez succeeded Dean Martinez has been Dr. Ruth presented his research Arthur Brissette, who had director of special projects, in at a meeting of the American served in these administrative the School of New Resources Chemical Soceity in 1973. capacities for the last five (adult undergraduate program) Dr. Ruth began research at years, and is returning to full at the College of New Rochelle. Clark University in 1972 and time teaching in the accounting In that position, she oversaw the completed the experiments at program of the department of Weekend College, programs of DEAN MARTINEZ Yale in the summer of 1973. His business at SHU. community service, outreach to paper entitled Levels in Dy as President Kidera said, “Miss community organizations, and consortium of five New York appreciation of the entire University community—for Populated from Decay of 158 Ho Martinez brings to Sacred Heart special programs in the area of colleges. She also has been a in Equilibrium with 2.3h 158 Er, University an unique personal and career coun language arts specialist in the your invaluable and dedicated service and leadership to investigates the accuracy of background in a wide range of selling. -

RIPON a Special Pre-Election Report

RIPON NOVEMBER, 1970 VOl. VI No. 11 ONE DOLLAR • The Raging Political Battles • The Apathetic Voter • The Stakes for Nixon in '72 A Special Pre-Election Report SUMMARY OF CONTENTS THE RIPON SOCIETY, INC. ~I~ o~:~:r!~:n :.-~ ~ bers are young business, acadamlc and professIonal men and wonnm. It has national headquarters in CambrIdge, Massachusatta, chapters In elmm EDITORIAL 3 cities, National AssocIate members throughout the fIfty states, and several affiliated groups of subchapter status. The SocIety is supported iIy cbspler dues, individual contributions and revenues from Its pUblications and con· tract work. The SocIety offers the followIng options for annual amtrIbu· RIPON: 'ENDORSEMENTS 5 tion: Contributor $25 or more: Sustalner $100 or more: Founder $1000 or more. Inquiries about membershIp and chapter organization abaIIId be addressad to the National Executlva Dlrectar. POLITICAL NOTES 6 NATIONAl GOVERNING BOARD OffIcers PRE-ELECTION REPORTS • Josiah Lea Auspitz, PresIdent 'Howard F. Gillett., Jr., Chairman of the Board 'Bruce K. Chapman, ChaIrman of the £Ie:utln CommIttee New York -10 'Mlchaei F. Brewer, VIca·Presldent • Robert L. Beal, Treasurer Pennsylvania -15 'Richard E. Beaman, Secretal1 Sastan Phlladalpbla "Robert Gulick 'Richard R. Block Martin A. Linsky Charles Day Ohio -18 Michael W. Christian Roger Whittlesey Combrldge Seattle 'Robert Davidson 'Thomas A. Alberg Texas -20 David A. Reil Camden Hail Rhea Kemble Wi lIIam Rodgers ChIcago WashIngton Massachusetts -23 ·R. Quincy White, Jr. 'Patricia A. Goldman 'Haroid S. Russell Stepben Herbits George H. Walker III Linda K. Lee Michigan -25 Dalles 'Neil D. Anderson At Large Howard L. Abramson "Chrlstopher T. Bayley Robert A. Wilson Thomas A. -

The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party: Background and Recent

THE MISSISSIPPI FREEDOM DEMOCRATIC PARTY Background lnformaUon for SUpportive Campaigns by Campus Groups repared by STEVE MAX Political Education ProJect, Room 309, 119 Firth Ave., N. Y .c. 10003 Associated with Students for a Democratic Society THE MISSISSIPPI FREEDOM DEMOCRATIC PARTY: BACKGROUND AND RECENT DEVELOPMENTS by STEVE IvlAX The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party was founded April 26, 1964 in order to create an opportunity for meaningful political expres sion for the 438,000 adult Negro Mississippians ~ho traditionally have been denied this right. In-addition to being a political instrument, the FDP provides a focus for the coordination of civil rights activity in the state and around the country. Although its memters do not necessarily· think in the se -terms, the MFDP is the organization above all others whose work is most directly forcing a realignment within the Democratic Party. All individuals and organizations who understand that ' when the Negro is not free, then all are in chains; who realize that the present system of discrimi nation precludes the abolition of poverty, and who have an interest in t he destruction of the Dixiecrat-Republican alliance and the purging of the racists from the Democratic Party are poteptial allies of the MFDP. BACKGROUND INFORMATION- The Mississippi Democratic Party runs the state of Mississippi _wit h an iron hand·. It controls the legislative, executive and judicial be nches of the state government. Prior to the November, 1964 elec tion all 49 state Senators and all but one of the 122 Representa tives were Democrats. Mississippi sent four Democrats and one Goldwater Republican to Congress last November.