Recording and Analysis of Bird Vocalizations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thinking with Birds: Mary Elizabeth Barber's Advocacy for Gender

Thinking with Birds: Mary Elizabeth Barber’s Advocacy for Gender Equality in Ornithology TANJA HAMMEL Department of History, University of Basel This article explores parts of the first South African woman ornithologist’s life and work. It concerns itself with the micro-politics of Mary Elizabeth Barber’s knowledge of birds from the 1860s to the mid-1880s. Her work provides insight into contemporary scientific practices, particularly the importance of cross-cultural collaboration. I foreground how she cultivated a feminist Darwinism in which birds served as corroborative evidence for female selection and how she negotiated gender equality in her ornithological work. She did so by constructing local birdlife as a space of gender equality. While male ornithologists naturalised and reinvigorated Victorian gender roles in their descriptions and depictions of birds, she debunked them and stressed the absence of gendered spheres in bird life. She emphasised the female and male birds’ collaboration and gender equality that she missed in Victorian matrimony, an institution she harshly criticised. Reading her work against the background of her life story shows how her personal experiences as wife and mother as well as her observation of settler society informed her view on birds, and vice versa. Through birds she presented alternative relationships to matrimony. Her protection of insectivorous birds was at the same time an attempt to stress the need for a New Woman, an aspect that has hitherto been overlooked in studies of the transnational anti-plumage -

Observebserve a D Dinosaurinosaur

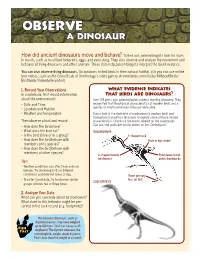

OOBSERVEBSERVE A DDINOSAURINOSAUR How did ancient dinosaurs move and behave? To fi nd out, paleontologists look for clues in fossils, such as fossilized footprints, eggs, and even dung. They also observe and analyze the movement and behavior of living dinosaurs and other animals. These data help paleontologists interpret the fossil evidence. You can also observe living dinosaurs. Go outdoors to fi nd birds in their natural habitat. (Or you can use online bird videos, such as the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s video gallery at www.birds.cornell.edu/AllAboutBirds/ BirdGuide/VideoGallery.html) 1. Record Your Observations What Evidence IndiCates In a notebook, fi rst record information That Birds Are Dinosaurs? about the environment: Over 125 years ago, paleontologists made a startling discovery. They • Date and Time recognized that the physical characteristics of modern birds and a • Location and Habitat species of small carnivorous dinosaur were alike. • Weather and temperature Take a look at the skeletons of roadrunner (a modern bird) and Coelophysis (an extinct dinosaur) to explore some of these shared Then observe a bird and record: characteristics. Check out the bones labeled on the roadrunner. • How does the bird move? Can you fi nd and label similar bones on the Coelophysis? • What does the bird eat? ROADRUNNER • Is the bird alone or in a group? S-shaped neck • How does the bird behave with Hole in hip socket members of its species? • How does the bird behave with members of other species? V-shaped furcula Pubis bone in hip (wishbone) points backwards Tips: • Weather conditions can affect how animals behave. -

BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis Mcintosh

COM . TOCK S HUTTER © S © BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis McIntosh For passionate birdwatcher Sandy Komito of over age 16 say they actively observe and try to iden- Fair Lawn, New Jersey, 1998 was a big year. In a tify birds, although few go to the extremes Komito tight competition with two fellow birders to see as did. About 88 percent are content to enjoy bird many species as possible in a single year, Komito watching in their own backyards or neighborhoods. traveled 270,000 miles, crisscrossing North Amer- More avid participants plan vacations around ica and voyaging far out to sea to locate rare and their hobby and sometimes travel long distances to elusive birds. In the end, he set a North American view a rare species and add it to their lifelong list of record of 748 species, topping his own previous birds spotted. Many birdwatchers, both casual and record of 726, which had stood for 11 years. serious, also function as citizen scientists, provid- Komito and his fellow competitors are not alone ing valuable data to help scientists monitor bird in their love of birds. According to a U.S. Fish and populations and create management guidelines to Wildlife Service survey, about one in five Americans protect species in decline. 36 2 0 1 4 N UMBER 1 | E NGLISH T E ACHING F ORUM Birding Basics The origins of bird watching in the United States date back to the late 1800s when conserva- tionists became concerned about the hunting of birds to supply feathers for the fashion industry. -

Beginning Birdwatching 2021 Resource List

Beginning Birdwatching 2021 Resource List Field Guides and how-to Birds of Illinois-Sheryl Devore and Steve Bailey The New Birder’s Guide to Birds of North America-Bill Thompson III Sibley’s Birding Basics-David Sibley Peterson Guide to Bird Identification-in 12 Steps-Howell and Sullivan Clubs and Organizations Chicago Ornithological Society-www.chicagobirder.org DuPage Birding Club-www.dupagebirding.org Evanston-North Shore Bird Club-www.ensbc.org Illinois Audubon Society-www.illinoisaudubon.org Will, Kane, Lake Cook county Audubon chapters (and others in Illinois) Illinois Ornithological Society-www.illinoisbirds.org Illinois Young Birders-(ages 9-18) monthly field trips and yearly symposiums Wild Things Conference 2021 American Birding Association- aba.org On-line Resources Cornell Lab of Ornithology All About Birds, eBird, Birdcast Radar, Macaulay Library (sounds), Youtube series: Inside Birding: Shape, Habitat, Behavior DuPage Birding Club-Youtube channel, Mini-tutorials, Bird-O-Bingo card, DuPage hot spot descriptions Facebook: Illinois Birding Network, Illinois Rare Bird Alert, World Girl Birders, Raptor ID, What’s this Bird? Birdnote-can subscribe for informative, weekly emails-also Podcast Birdwatcher’s Digest podcasts: Out There With the Birds, Birdsense Podcasts: Laura Erickson’s For the Birds, Ray Brown’s Talkin’ Birds, American Birding Podcast (ABA) Blog: Jeff Reiter’s “Words on Birds” (meet Jeff on his monthly walks at Cantigny, see DuPage Birding Club website for schedule) Illinois Birding by County-countywiki.ilbirds.com -

Ment for Advanoed Ornithology (Zoology 119) at the University of Michigan Biological Station, Cheboygan, Michigan

THE LIFE HISTORY THE RUBY-THROATED HUMBBIHGBIRD .by -- J, Reuben Sandve Minneapolis, Minnesota A report of an original field study conduotsd aa a require- ment for Advanoed Ornithology (Zoology 119) at the University of Michigan Biological Station, Cheboygan, Michigan. +4 f q3 During the summer of 1943 while at the Univereity of Michigan Biological Station in Cheboygam County, Michigan, I was afforded fhe opportunity of making eon8 observations- - on the nesting habits of the Ruby-throated Hummingbird (Archl- lochue colubrie). Observations were carried on far a two week period starting July 7 when a nest with two young waa . discovered and terminating on July 21, on whloh day the young left the nest. Although obeerrafions on a number of nests would have been more satiefaotory, no attempt was mMe to find additional nests both because of the latenese of the seaeon and the unlikehihood of finding any withln the Station area. The purpoae of this study has been to gain further in- formation on a necessarily limited phase of the life hlstory of the Ruby-throated Hummingbird which would contribute 1,n a emall way to a better understanding of its habite and behavior. Observations were made almoet exclusively from a tower blind whose floor was located four feet from the nest. A limited amount of observation was done outside of the blind with a pair of eight power binoculars. I -Nest The nest waa located in a small Whlte Birch (Betula -alba) about 22 feet from the ground and plaoed four feet out on a limb which was one-half Inch in diameter, It -

Career Opportunities in Ornithology

AMERICAN BIRDS SPECIAL REPORT CareerOpportunities in Ornithology Preparedby TheAmerican Ornithologists' Union }study of birds, encompasses bothRNITHOLOGY, professionalTHEand SCIENTIFIC amateur endeavors.All aspectsof the biology of birds--ecology, behavior, anat- omy, physiology,systematics and ev- olution, veterinary sciences, wildlife management, and conservation--are topicsof interest.This broad field pro- videscareer opportunitiesin research, education, and administration, but there is intense competition for the limited number of positionsavailable eachyear. At leasta Bachelor'sdegree is necessaryto be competitive at the entry level; more often a Master's de- greeis required, and a Ph.D. is essen- tial for advancedpositions. Aspiring ornithologistsshould understandthe kinds of jobs available and carefully study the various degreeprograms of- fered at collegesand universities.This article introduces these opportunities and requirements. Professionalornithologists are biol- ogistswho specialize in the study of birds. More than 2000 individuals in North Americawork in jobs involving ornithology. Most either teach in col- legesor universitiesor are employed by federal or state agencies. Some work in university or public mu- seums, and some work for private conservation and research organiza- tions or consultingfirms. Most ornithologists divide their time between teaching and research or betweenteaching and administra- tion. A museum curator also may teach at a university. In general,sala- riesfor professionalornithologists are quite low compared with those avail- able in the businessand professional world, but personal fulfillment and intense interest in the work provides another aspectof compensation. Flex- ible work schedules,field work in ad- Trackingreleased Burrowing Owls with radio receiver.Photograph/Ellen Lawler. Volume 43, Number I 29 [ BandingSemipalrnated Sandpiper chick Photograph/PainMiller Close-upphotography of btrd. -

2010 Ornithology (B/C) - Training Handout

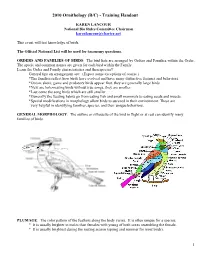

2010 Ornithology (B/C) - Training Handout KAREN LANCOUR National Bio Rules Committee Chairman [email protected] This event will test knowledge of birds. The Official National List will be used for taxonomy questions. ORDERS AND FAMILIES OF BIRDS: The bird lists are arranged by Orders and Families within the Order. The specie and common names are given for each bird within the Family. Learn the Order and Family characteristics and then species!! General tips on arrangement are: (Expect some exceptions of course.) *The families reflect how birds have evolved and have many distinctive features and behaviors. *Ocean, shore, game and predatory birds appear first, they are generally large birds. *Next are hole-nesting birds without true songs, they are smaller. *Last come the song birds which are still smaller. *Generally the feeding habits go from eating fish and small mammals to eating seeds and insects. *Special modifications in morphology allow birds to succeed in their environment. These are very helpful in identifying families, species, and their unique behaviors. GENERAL MORPHOLOGY: The outline or silhouette of the bird in flight or at rest can identify many families of birds. PLUMAGE: The color pattern of the feathers along the body varies. It is often unique for a species. * It is usually brighter in males than females with young of both sexes resembling the female. * It is usually brightest during the mating season (spring and summer for most birds). 1 HEAD: Many have distinctive stripes or colored patches on their head. * Crown = tip of the head and Cap = a distinctively colored crown as black-capped chickadees. -

Forensic Ornithology

FORENSIC ORNITHOLOGY Carla J. Dove Division of Birds Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC 20560 INTRODUCTION Feathers are among the most uniquely designed, beautiful structures in nature and have evolved to serve a variety of functions (e.g. protection, recognition, attraction, aerodynamics, insulation). While there are many different types of feathers on a single bird’s body (e.g., contour, semiplume, down, bristle, filoplume), the contour (body, wing and tail) feathers are the most diagnostic to the casual observer. Recognizing the plumage (a collective term for all of the feathers that cover the bird’s body) is one of the most common ways that we identify the many different species of birds. The individual feathers (which together make up the plumage) also vary among and within species, and even exhibit differences on a single bird’s body. For example, examination of the plumage of a male Mallard Duck (Anas platyrhynchos) reveals different colors, shapes, textures, sizes, and patterns on most every part of the body. In addition, each contour feather is generally made up of different types of barbs - 1) Pennaceous barbs are stiff and make up the feather vanes which give color, pattern and texture to the whole feather, 2) Plumulaceous (downy) barbs are fluffy, soft barbs located at the base of most contour feathers and are thought to aid in insulation. Although these two types of barbs have homologous structures, they appear very different from each other when viewed with light microscopy. The reasons for these morphological differences are not truly known but could be due to functional constraints on each part of the feather (e.g. -

2020 North Carolina Ornithology List

2020 North Carolina Ornithology List Kingdom – ANIMALIA Phylum – CHORDATA Key: Sub Phylum – VERTEBRATA Regional level (62 in total) Class – AVES Addition for State level (110 in total) Family Grou p (Family Name) Addition for National level (160 in total) Common Name [Scientific name is in italics] ORDER: Anseriformes Ibises and Spoonbills ORDER: Charadriiformes Ducks, Geese, and Swans (Anatidae) (Threskiornithidae) Lapwings and Plovers (Charadriidae) Northern Shoveler Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja American Golden-Plover Green-winged Teal Killdeer Charadrius vociferus Canvasback ORDER: Suliformes Oystercatchers (Haematopodidae) Hooded Merganser Cormorants (Phalacrocoracidae) American Oystercatcher Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Double-crested Cormorant Stilts and Avocets (Recurvirostridae) Snow Goose Chen caerulescens Phalacrocorax auritus Black-necked Stilt Canada Goose Branta canadensis Darters (Anhingidae) American Avocet Recurvirostra Trumpeter Swan Anhinga Anhinga anhinga americana Wood Duck Aix sponsa Frigatebirds (Fregatidae) Sandpipers, Phalaropes, and Allies Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Magnificent Frigatebird (Scolopacidae) Cinnamon Teal Anas cyanoptera American Woodcock Scolopax minor ORDER: Ciconiiformes Spotted Sandpiper ORDER: Galliformes Deep-water Waders (Ciconiidae) Ruddy Turnstone Partridges, Grouse, Turkeys, and Old Wood stork Dunlin Calidris alpina World Quail Wilson’s Snipe (Phasianidae ) ORDER: Falconiformes Gulls, Terns, and Skimmers Ring-necked Pheasant Caracaras and Falcons (Falconidae) (Laridae) Ruffed Grouse -

2020 National Bird List

2020 NATIONAL BIRD LIST See General Rules, Eye Protection & other Policies on www.soinc.org as they apply to every event. Kingdom – ANIMALIA Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias ORDER: Charadriiformes Phylum – CHORDATA Snowy Egret Egretta thula Lapwings and Plovers (Charadriidae) Green Heron American Golden-Plover Subphylum – VERTEBRATA Black-crowned Night-heron Killdeer Charadrius vociferus Class - AVES Ibises and Spoonbills Oystercatchers (Haematopodidae) Family Group (Family Name) (Threskiornithidae) American Oystercatcher Common Name [Scientifc name Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja Stilts and Avocets (Recurvirostridae) is in italics] Black-necked Stilt ORDER: Anseriformes ORDER: Suliformes American Avocet Recurvirostra Ducks, Geese, and Swans (Anatidae) Cormorants (Phalacrocoracidae) americana Black-bellied Whistling-duck Double-crested Cormorant Sandpipers, Phalaropes, and Allies Snow Goose Phalacrocorax auritus (Scolopacidae) Canada Goose Branta canadensis Darters (Anhingidae) Spotted Sandpiper Trumpeter Swan Anhinga Anhinga anhinga Ruddy Turnstone Wood Duck Aix sponsa Frigatebirds (Fregatidae) Dunlin Calidris alpina Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Magnifcent Frigatebird Wilson’s Snipe Northern Shoveler American Woodcock Scolopax minor Green-winged Teal ORDER: Ciconiiformes Gulls, Terns, and Skimmers (Laridae) Canvasback Deep-water Waders (Ciconiidae) Laughing Gull Hooded Merganser Wood Stork Ring-billed Gull Herring Gull Larus argentatus ORDER: Galliformes ORDER: Falconiformes Least Tern Sternula antillarum Partridges, Grouse, Turkeys, and -

Trapping White Ibises with Rocket Nets and Mist Nets in the Florida Everglades

J. Field Ornithol. 74(2):187±192, 2003 Trapping White Ibises with rocket nets and mist nets in the Florida Everglades Julie A. Heath1 and Peter C. Frederick Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611 USA Received 30 April 2002; accepted 19 September 2002 ABSTRACT. We lured White Ibises (Eudocimus albus) to trap sites with decoy plastic ¯amingos and captured them with a rocket net or mist nets. Our ability to attract ibises to a site (and consequently our capture success) was affected by vegetation height and water depth but not by decoy numbers or their arrangement. Both the rocket net (37 ibises) and mist nets (97 ibises) caught birds. The number of birds captured per day was the same for both methods, but the rocket net trap captured more birds per set than did mist nets. Because mist nets were easy to reset we captured 1±2 birds per set multiple times in one day with mist nets. We preferred mist nets over rocket net traps because mist nets allowed for shorter bird processing times, greater ease of set up, and fewer safety considerations for transport and operation of the trap. Also, rocket nets required more equipment and expense. Although we discouraged other species from landing at a trap site, there was evidence that these techniques may also be useful for capturing other wading birds. SINOPSIS. Captura de ciguenÄas (Eudocimus albus) con redes de cohetes y redes de niebla en la Florida Atraimos ciguenÄas (Eudocimus albus) a lugares particulares utilizando senÄuelos de ¯amencos para atraparlas con redes de cohetes y con redes de niebla. -

Migration of Birds Circular 16

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Migration of Birds Circular 16 Migration of Birds Circular 16 by Frederick C. Lincoln, 1935 revised by Steven R. Peterson, 1979 revised by John L. Zimmerman, 1998 Division of Biology, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS Associate editor Peter A. Anatasi Illustrated by Bob Hines U.S. FISH & WILDLIFE SERVICE D E R P O A I R R E T T M N EN I T OF THE U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE..............................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................2 EARLY IDEAS ABOUT MIGRATION............................................................4 TECHNIQUES FOR STUDYING MIGRATION..........................................6 Direct Observation ....................................................................................6 Aural ............................................................................................................7 Preserved Specimens ................................................................................7 Marking ......................................................................................................7 Radio Tracking ..........................................................................................8 Radar Observation ....................................................................................9 EVOLUTION OF MIGRATION......................................................................10