Seasonal Climate Impacts on Vocal Activity in Two Neotropical Nonpasserines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Costa Rica 2020

Sunrise Birding LLC COSTA RICA TRIP REPORT January 30 – February 5, 2020 Photos: Talamanca Hummingbird, Sunbittern, Resplendent Quetzal, Congenial Group! Sunrise Birding LLC COSTA RICA TRIP REPORT January 30 – February 5, 2020 Leaders: Frank Mantlik & Vernon Campos Report and photos by Frank Mantlik Highlights and top sightings of the trip as voted by participants Resplendent Quetzals, multi 20 species of hummingbirds Spectacled Owl 2 CR & 32 Regional Endemics Bare-shanked Screech Owl 4 species Owls seen in 70 Black-and-white Owl minutes Suzy the “owling” dog Russet-naped Wood-Rail Keel-billed Toucan Great Potoo Tayra!!! Long-tailed Silky-Flycatcher Black-faced Solitaire (& song) Rufous-browed Peppershrike Amazing flora, fauna, & trails American Pygmy Kingfisher Sunbittern Orange-billed Sparrow Wayne’s insect show-and-tell Volcano Hummingbird Spangle-cheeked Tanager Purple-crowned Fairy, bathing Rancho Naturalista Turquoise-browed Motmot Golden-hooded Tanager White-nosed Coati Vernon as guide and driver January 29 - Arrival San Jose All participants arrived a day early, staying at Hotel Bougainvillea. Those who arrived in daylight had time to explore the phenomenal gardens, despite a rain storm. Day 1 - January 30 Optional day-trip to Carara National Park Guides Vernon and Frank offered an optional day trip to Carara National Park before the tour officially began and all tour participants took advantage of this special opportunity. As such, we are including the sightings from this day trip in the overall tour report. We departed the Hotel at 05:40 for the drive to the National Park. En route we stopped along the road to view a beautiful Turquoise-browed Motmot. -

Panama's Top Birding Lodges

TOP BIRDING LODGES OF PANAMA WITH IOS: JUNE 26 – JULY 5, 2018 TOP BIRDING LODGES OF PANAMA with the Illinois Ornithological Society June 26-July 5, 2018 Guides: Adam Sell and Josh Engel with local guides Check out the trip photo gallery at www.redhillbirding.com/panama2018gallery2 Panama may not be as well-known as Costa Rica as a birding and wildlife destination, but it is every bit as good. With an incredible diversity of birds in a small area, wonderful lodges, and great infrastructure, we tallied more than 300 species while staying at two of the best birding lodges anywhere in Central America. While staying at Canopy Tower, we birded Pipeline Road and other lowland sites in Soberanía National Park and spent a day in the higher elevations of Cerro Azul. We then shifted to Canopy Lodge in the beautiful, cool El Valle de Anton, birding the extensive forests around El Valle and taking a day trip to coastal wetlands and the nearby drier, more open forests in that area. This was the rainy season in Panama, but rain hardly interfered with our birding at all and we generally had nice weather throughout the trip. The birding, of course, was excellent! The lodges themselves offered great birding, with a fruiting Cecropia tree next to the Canopy Tower which treated us to eye-level views of tanagers, toucans, woodpeckers, flycatchers, parrots, and honeycreepers. Canopy Lodge’s feeders had a constant stream of birds, including Gray-cowled Wood-Rail and Dusky-faced Tanager. Other bird highlights included Ocellated and Dull-mantled Antbirds, Pheasant Cuckoo, Common Potoo sitting on an egg(!), King Vulture, Black Hawk-Eagle being harassed by Swallow-tailed Kites, five species of motmots, five species of trogons, five species of manakins, and 21 species of hummingbirds. -

Northwest Argentina (Custom Tour) 13 – 24 November, 2015 Tour Leader: Andrés Vásquez Co-Guided by Sam Woods

Northwest Argentina (custom tour) 13 – 24 November, 2015 Tour leader: Andrés Vásquez Co-guided by Sam Woods Trip Report by Andrés Vásquez; most photos by Sam Woods, a few by Andrés V. Elegant Crested-Tinamou at Los Cardones NP near Cachi; photo by Sam Woods Introduction: Northwest Argentina is an incredible place and a wonderful birding destination. It is one of those locations you feel like you are crossing through Wonderland when you drive along some of the most beautiful landscapes in South America adorned by dramatic rock formations and deep-blue lakes. So you want to stop every few kilometers to take pictures and when you look at those shots in your camera you know it will never capture the incredible landscape and the breathtaking feeling that you had during that moment. Then you realize it will be impossible to explain to your relatives once at home how sensational the trip was, so you breathe deeply and just enjoy the moment without caring about any other thing in life. This trip combines a large amount of quite contrasting environments and ecosystems, from the lush humid Yungas cloud forest to dry high Altiplano and Puna, stopping at various lakes and wetlands on various altitudes and ending on the drier upper Chaco forest. Tropical Birding Tours Northwest Argentina, Nov.2015 p.1 Sam recording memories near Tres Cruces, Jujuy; photo by Andrés V. All this is combined with some very special birds, several endemic to Argentina and many restricted to the high Andes of central South America. Highlights for this trip included Red-throated -

Acoustic Monitoring of Night-Migrating Birds: a Progress Report

Acoustic Monitoring of Night-Migrating Birds: A Progress Report William R. Evans Kenneth V. Rosenberg Abstract—This paper discusses an emerging methodology that to give regular vocalizations in night migration are the vireos uses electronic technology to monitor vocalizations of night-migrat- (Vireonidae), flycatchers (Tyrannidae), and orioles (Icterinae). ing birds. On a good migration night in eastern North America, If a monitoring protocol is consistently maintained, an array thousands of call notes may be recorded from a single ground-based, of microphone stations can provide information on how the audio-recording station, and an array of recording stations across a species composition and number of vocal migrants vary across region may serve as a “recording net” to monitor a broad front of time and space. Such data have application for monitoring migration. Data from pilot studies in Florida, Texas, New York, and avian populations and identifying their migration routes. In British Columbia illustrate the potential of this technique to gather addition, detection and classification of distinctive call-types information that cannot be gathered by more conventional methods, is possible with computers (Mills 1995; Taylor 1995), thus such as mist-netting or diurnal counts. For example, the Texas information on bird populations might be gained automati- station detected a major migration of grassland sparrows, and a cally. In this paper, we summarize the current state of station in British Columbia detected hundreds of Swainson’s knowledge for identifying night-flight calls to species; present Thrushes; both phenomena were not detected with ground monitor- selected results from four ongoing studies that are monitoring ing efforts. -

Systematic Relationships and Biogeography of the Tracheophone Suboscines (Aves: Passeriformes)

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 23 (2002) 499–512 www.academicpress.com Systematic relationships and biogeography of the tracheophone suboscines (Aves: Passeriformes) Martin Irestedt,a,b,* Jon Fjeldsaa,c Ulf S. Johansson,a,b and Per G.P. Ericsona a Department of Vertebrate Zoology and Molecular Systematics Laboratory, Swedish Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 50007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden b Department of Zoology, University of Stockholm, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden c Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark Received 29 August 2001; received in revised form 17 January 2002 Abstract Based on their highly specialized ‘‘tracheophone’’ syrinx, the avian families Furnariidae (ovenbirds), Dendrocolaptidae (woodcreepers), Formicariidae (ground antbirds), Thamnophilidae (typical antbirds), Rhinocryptidae (tapaculos), and Conop- ophagidae (gnateaters) have long been recognized to constitute a monophyletic group of suboscine passerines. However, the monophyly of these families have been contested and their interrelationships are poorly understood, and this constrains the pos- sibilities for interpreting adaptive tendencies in this very diverse group. In this study we present a higher-level phylogeny and classification for the tracheophone birds based on phylogenetic analyses of sequence data obtained from 32 ingroup taxa. Both mitochondrial (cytochrome b) and nuclear genes (c-myc, RAG-1, and myoglobin) have been sequenced, and more than 3000 bp were subjected to parsimony and maximum-likelihood analyses. The phylogenetic signals in the mitochondrial and nuclear genes were compared and found to be very similar. The results from the analysis of the combined dataset (all genes, but with transitions at third codon positions in the cytochrome b excluded) partly corroborate previous phylogenetic hypotheses, but several novel arrangements were also suggested. -

Natural History and Breeding Behavior of the Tinamou, Nothoprocta Ornata

THE AUK A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ORNITHOLOGY VoL. 72 APRIL, 1955 No. 2 NATURAL HISTORY AND BREEDING BEHAVIOR OF THE TINAMOU, NOTHOPROCTA ORNATA ON the high mountainous plain of southern Peril west of Lake Titicaca live three speciesof the little known family Tinamidae. The three speciesrepresent three different genera and grade in size from the small, quail-sizedNothura darwini found in the farin land and grassy hills about Lake Titicaca between 12,500 and 13,300 feet to the large, pheasant-sized Tinamotis pentlandi in the bleak country between 14,000 and 16,000 feet. Nothoproctaornata, the third species in this area and the one to be discussedin the present report, is in- termediate in size and generally occurs at intermediate elevations. In Peril we have encountered Nothoproctabetween 13,000 and 14,300 feet. It often lives in the same grassy areas as Nothura; indeed, the two speciesmay be flushed simultaneouslyfrom the same spot. This is not true of Nothoproctaand the larger tinamou, Tinamotis, for although at places they occur within a few hundred yards of each other, Nothoproctais usually found in the bunch grassknown locally as ichu (mostly Stipa ichu) or in a mixture of ichu and tola shrubs, whereas Tinamotis usually occurs in the range of a different bunch grass, Festuca orthophylla. The three speciesof tinamous are dis- tinguished by the inhabitants, some of whom refer to Nothura as "codorniz" and to Nothoproctaas "perdiz." Tinamotis is always called "quivia," "quello," "keu," or some similar derivative of its distinctive call. The hilly, almost treeless countryside in which Nothoproctalives in southern Peril is used primarily for grazing sheep, alpacas,llamas, and cattle. -

Thinking with Birds: Mary Elizabeth Barber's Advocacy for Gender

Thinking with Birds: Mary Elizabeth Barber’s Advocacy for Gender Equality in Ornithology TANJA HAMMEL Department of History, University of Basel This article explores parts of the first South African woman ornithologist’s life and work. It concerns itself with the micro-politics of Mary Elizabeth Barber’s knowledge of birds from the 1860s to the mid-1880s. Her work provides insight into contemporary scientific practices, particularly the importance of cross-cultural collaboration. I foreground how she cultivated a feminist Darwinism in which birds served as corroborative evidence for female selection and how she negotiated gender equality in her ornithological work. She did so by constructing local birdlife as a space of gender equality. While male ornithologists naturalised and reinvigorated Victorian gender roles in their descriptions and depictions of birds, she debunked them and stressed the absence of gendered spheres in bird life. She emphasised the female and male birds’ collaboration and gender equality that she missed in Victorian matrimony, an institution she harshly criticised. Reading her work against the background of her life story shows how her personal experiences as wife and mother as well as her observation of settler society informed her view on birds, and vice versa. Through birds she presented alternative relationships to matrimony. Her protection of insectivorous birds was at the same time an attempt to stress the need for a New Woman, an aspect that has hitherto been overlooked in studies of the transnational anti-plumage -

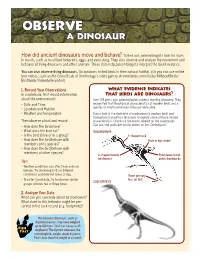

Observebserve a D Dinosaurinosaur

OOBSERVEBSERVE A DDINOSAURINOSAUR How did ancient dinosaurs move and behave? To fi nd out, paleontologists look for clues in fossils, such as fossilized footprints, eggs, and even dung. They also observe and analyze the movement and behavior of living dinosaurs and other animals. These data help paleontologists interpret the fossil evidence. You can also observe living dinosaurs. Go outdoors to fi nd birds in their natural habitat. (Or you can use online bird videos, such as the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s video gallery at www.birds.cornell.edu/AllAboutBirds/ BirdGuide/VideoGallery.html) 1. Record Your Observations What Evidence IndiCates In a notebook, fi rst record information That Birds Are Dinosaurs? about the environment: Over 125 years ago, paleontologists made a startling discovery. They • Date and Time recognized that the physical characteristics of modern birds and a • Location and Habitat species of small carnivorous dinosaur were alike. • Weather and temperature Take a look at the skeletons of roadrunner (a modern bird) and Coelophysis (an extinct dinosaur) to explore some of these shared Then observe a bird and record: characteristics. Check out the bones labeled on the roadrunner. • How does the bird move? Can you fi nd and label similar bones on the Coelophysis? • What does the bird eat? ROADRUNNER • Is the bird alone or in a group? S-shaped neck • How does the bird behave with Hole in hip socket members of its species? • How does the bird behave with members of other species? V-shaped furcula Pubis bone in hip (wishbone) points backwards Tips: • Weather conditions can affect how animals behave. -

Checklistccamp2016.Pdf

2 3 Participant’s Name: Tour Company: Date#1: / / Tour locations Date #2: / / Tour locations Date #3: / / Tour locations Date #4: / / Tour locations Date #5: / / Tour locations Date #6: / / Tour locations Date #7: / / Tour locations Date #8: / / Tour locations Codes used in Column A Codes Sample Species a = Abundant Red-lored Parrot c = Common White-headed Wren u = Uncommon Gray-cheeked Nunlet r = Rare Sapayoa vr = Very rare Wing-banded Antbird m = Migrant Bay-breasted Warbler x = Accidental Dwarf Cuckoo (E) = Endemic Stripe-cheeked Woodpecker Species marked with an asterisk (*) can be found in the birding areas visited on the tour outside of the immediate Canopy Camp property such as Nusagandi, San Francisco Reserve, El Real and Darien National Park/Cerro Pirre. Of course, 4with incredible biodiversity and changing environments, there is always the possibility to see species not listed here. If you have a sighting not on this list, please let us know! No. Bird Species 1A 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Tinamous Great Tinamou u 1 Tinamus major Little Tinamou c 2 Crypturellus soui Ducks Black-bellied Whistling-Duck 3 Dendrocygna autumnalis u Muscovy Duck 4 Cairina moschata r Blue-winged Teal 5 Anas discors m Curassows, Guans & Chachalacas Gray-headed Chachalaca 6 Ortalis cinereiceps c Crested Guan 7 Penelope purpurascens u Great Curassow 8 Crax rubra r New World Quails Tawny-faced Quail 9 Rhynchortyx cinctus r* Marbled Wood-Quail 10 Odontophorus gujanensis r* Black-eared Wood-Quail 11 Odontophorus melanotis u Grebes Least Grebe 12 Tachybaptus dominicus u www.canopytower.com 3 BirdChecklist No. -

The All-Bird Bulletin

Advancing Integrated Bird Conservation in North America Spring 2014 Inside this issue: The All-Bird Bulletin Protecting Habitat for 4 the Buff-breasted Sandpiper in Bolivia The Neotropical Migratory Bird Conservation Conserving the “Jewels 6 Act (NMBCA): Thirteen Years of Hemispheric in the Crown” for Neotropical Migrants Bird Conservation Guy Foulks, Program Coordinator, Division of Bird Habitat Conservation, U.S. Fish and Bird Conservation in 8 Wildlife Service (USFWS) Costa Rica’s Agricultural Matrix In 2000, responding to alarming declines in many Neotropical migratory bird popu- Uruguayan Rice Fields 10 lations due to habitat loss and degradation, Congress passed the Neotropical Migra- as Wintering Habitat for tory Bird Conservation Act (NMBCA). The legislation created a unique funding Neotropical Shorebirds source to foster the cooperative conservation needed to sustain these species through all stages of their life cycles, which occur throughout the Western Hemi- Conserving Antigua’s 12 sphere. Since its first year of appropriations in 2002, the NMBCA has become in- Most Critical Bird strumental to migratory bird conservation Habitat in the Americas. Neotropical Migratory 14 Bird Conservation in the The mission of the North American Bird Heart of South America Conservation Initiative is to ensure that populations and habitats of North Ameri- Aros/Yaqui River Habi- 16 ca's birds are protected, restored, and en- tat Conservation hanced through coordinated efforts at in- ternational, national, regional, and local Strategic Conservation 18 levels, guided by sound science and effec- in the Appalachians of tive management. The NMBCA’s mission Southern Quebec is to achieve just this for over 380 Neo- tropical migratory bird species by provid- ...and more! Cerulean Warbler, a Neotropical migrant, is a ing conservation support within and be- USFWS Bird of Conservation Concern and listed as yond North America—to Latin America Vulnerable on the International Union for Conser- Coordination and editorial vation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. -

Count Summary Report Printout Date: 11/11/2016

Count Summary Report Printout Date: 11/11/2016 Count Name: Monteverde, Costa Count Code: CRMO Count Date: 12/19/2001 Rica # of Party Hours: 257.00 Species reported on count date: 376 Organizations & Sponsors: Weather Temperature Minimum: 59.0 Celsius Maximum: 77.0 Celsius Wind Direction Northeast Wind Velocity Minimum: 0.00 Kilometers/hour Maximum: 6.00 Kilometers/hour Snow Depth Minimum: 0.00 Centimeters Maximum: 0.00 Centimeters Still Water Open Moving Water Open AM and PM Conditions Cloud Cover AM: Clear PM: Cloudy AM Rain None AM Snow None PM Rain Light PM Snow None Start & End Times Start time End time 12:00 AM 10:00 AM Effort Observers In Field Total Number: 70 Minimum Number of Parties (daylight): 19 Maximum Number of Parties (daylight): 24 At Feeders Total Number: 0 Party Hours and Distance (excludes viewing at feeders and nocturnal birding) By Hours Distance Units Foot 239.00 114.00 Kilometers Car 18.00 85.00 Kilometers Air All-Terrain Vehicle Page 1 of 12 pages Count Summary Report Printout Date: 11/11/2016 Bicycle Dog Sled Golfcart Horseback Motorized Boat Non-Motorized Boat Skis/Xc-Skis Snowmachine Snowshoe Wheelchair Other Time and Distance Hours Distance Units At Feeders 0.00 Nocturnal Birding 17.00 26.00 Miles Total Party 257.00 199.00 Kilometers Checklist Species Number Number/Party Hrs. Flags Editorial Codes Highland Tinamou 3 0.0117 Great Tinamou 2 0.0078 Gray-headed Chachalaca 33 0.1284 Crested Guan 20 0.0778 Black Guan 18 0.0700 Black-breasted Wood-Quail 56 0.2179 Least Grebe 5 0.0195 Anhinga 1 0.0039 Fasciated Tiger-Heron -

BIRDS of COLOMBIA - MP3 Sound Collection List of Recordings

BIRDS OF COLOMBIA - MP3 sound collection List of recordings 0003 1 Tawny-breasted Tinamou 1 Song 0:07 Nothocercus julius (26/12/1993 , Podocarpus Cajanuma, Loja, Ecuador, 04.20S,79.10W) © Peter Boesman 0003 2 Tawny-breasted Tinamou 2 Song 0:23 Nothocercus julius (26/5/1996 06:30h, Páramo El Angel (Pacific slope), Carchi, Ecuador, 00.45N,78.03W) © Niels Krabbe 0003 3 Tawny-breasted Tinamou 3 Song () 0:30 Nothocercus julius (12/8/2006 14:45h, Betania area, Tachira, Venezuela, 07.29N,72.24W) © Nick Athanas. 0004 1 Highland Tinamou 1 Song 0:28 Nothocercus bonapartei (26/3/1995 07:15h, Rancho Grande area, Aragua, Venezuela, 10.21N,67.42W) © Peter Boesman 0004 2 Highland Tinamou 2 Song 0:23 Nothocercus bonapartei (10/3/2006 , Choroni road, Aragua, Venezuela, 10.22N,67.35W) © David Van den Schoor 0004 3 Highland Tinamou 3 Song 0:45 Nothocercus bonapartei (March 2009, Rancho Grande area, Aragua, Venezuela, 10.21N,67.42W) © Hans Matheve. 0004 4 Highland Tinamou 4 Song 0:40 Nothocercus bonapartei bonapartei. RNA Reinita Cielo Azul, San Vicente de Chucurí, Santander, Colombia, 1700m, 06:07h, 02-12-2007, N6.50'47" W73.22'30", song. also: Spotted Barbtail, Andean Emerald, Green Violetear © Nick Athanas. 0006 1 Gray Tinamou 1 Song 0:43 Tinamus tao (15/8/2007 18:30h, Nirgua area, San Felipe, Venezuela, 10.15N,68.30W) © Peter Boesman 0006 2 Gray Tinamou 2 Song 0:32 Tinamus tao (4/6/1995 06:15h, Palmichal area, Carabobo, Venezuela, 10.21N,68.12W) (background: Rufous-and-white Wren). © Peter Boesman 0006 3 Gray Tinamou 3 Song 0:04 Tinamus tao (1/2/2006 , Cerro Humo, Sucre, Venezuela, 10.41N,62.37W) © Mark Van Beirs.