Heronrymap:Africa - Mapping the Distribution and Status of Breeding Sites of Ardeids and Other Colonial Waterbirds in Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 2020.Indd

BROWN PELICAN Photo by Rob Swindell at Melbourne, Florida JANUARY 2020 Editors: Jim Jablonski, Marty Ackermann, Tammy Martin, Cathy Priebe Webmistress: Arlene Lengyel January 2020 Program Tuesday, January 7, 2020, 7 p.m. Carlisle Reservation Visitor Center Gulls 101 Chuck Slusarczyk, Jr. "I'm happy to be presenting my program Gulls 101 to the good people of Black River Audubon. Gulls are notoriously difficult to identify, but I hope to at least get you looking at them a little closer. Even though I know a bit about them, I'm far from an expert in the field and there is always more to learn. The challenge is to know the particular field marks that are most important, and familiarization with the many plumage cycles helps a lot too. No one will come out of this presentation an expert, but I hope that I can at least give you an idea what to look for. At the very least, I hope you enjoy the photos. Looking forward to seeing everyone there!” Chuck Slusarczyk is an avid member of the Ohio birding community, and his efforts to assist and educate novice birders via social media are well known, yet he is the first to admit that one never stops learning. He has presented a number of programs to Black River Audubon, always drawing a large, appreciative gathering. 2019 Wellington Area Christmas Bird Count The Wellington-area CBC will take place Saturday, December 28, 2019. Meet at the McDonald’s on Rt. 58 at 8:00 a.m. The leader is Paul Sherwood. -

The Exchange of Water Between Prince William Sound and the Gulf of Alaska Recommended

The exchange of water between Prince William Sound and the Gulf of Alaska Item Type Thesis Authors Schmidt, George Michael Download date 27/09/2021 18:58:15 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/5284 THE EXCHANGE OF WATER BETWEEN PRINCE WILLIAM SOUND AND THE GULF OF ALASKA RECOMMENDED: THE EXCHANGE OF WATER BETWEEN PRIMCE WILLIAM SOUND AND THE GULF OF ALASKA A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the University of Alaska in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE by George Michael Schmidt III, B.E.S. Fairbanks, Alaska May 197 7 ABSTRACT Prince William Sound is a complex fjord-type estuarine system bordering the northern Gulf of Alaska. This study is an analysis of exchange between Prince William Sound and the Gulf of Alaska. Warm, high salinity deep water appears outside the Sound during summer and early autumn. Exchange between this ocean water and fjord water is a combination of deep and intermediate advective intrusions plus deep diffusive mixing. Intermediate exchange appears to be an annual phen omenon occurring throughout the summer. During this season, medium scale parcels of ocean water centered on temperature and NO maxima appear in the intermediate depth fjord water. Deep advective exchange also occurs as a regular annual event through the late summer and early autumn. Deep diffusive exchange probably occurs throughout the year, being more evident during the winter in the absence of advective intrusions. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Appreciation is extended to Dr. T. C. Royer, Dr. J. M. Colonell, Dr. R. T. Cooney, Dr. R. -

Ardea Cinerea (Grey Heron) Family: Ardeidae (Herons and Egrets) Order: Ciconiiformes (Storks, Herons and Ibises) Class: Aves (Birds)

UWU The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour Ardea cinerea (Grey Heron) Family: Ardeidae (Herons and Egrets) Order: Ciconiiformes (Storks, Herons and Ibises) Class: Aves (Birds) Fig. 1. Grey heron, Ardea cinerea. [http://www.google.tt/imgres?imgurl=http://www.bbc.co.uk/lancashire/content/images/2006/06/15/grey_heron, downloaded 14 November 2012] TRAITS. Grey herons are large birds that can be 90-100cm tall and an adult could weigh in at approximately 1.5 kg. They are identified by their long necks and very powerful dagger like bills (Briffett 1992). They have grey plumage with long black head plumes and their neck is white with black stripes on the front. In adults the forehead sides of the head and the centre of the crown are white. In flight the neck is folded back with the wings bowed and the flight feathers are black. Each gender looks alike except for the fact that females have shorter heads (Seng and Gardner 1997). The juvenile is greyer without black markings on the head and breast. They usually live long with a life span of 15-24 years. ECOLOGY. The grey heron is found in Europe, Asia and Africa, and has been recorded as an accidental visitor in Trinidad. Grey herons occur in many different habitat types including savannas, ponds, rivers, streams, lakes and temporary pools, coastal brackish water, wetlands, marsh and swamps. Their distribution may depend on the availability of shallow water (brackish, saline, fresh, flowing and standing) (Briffett 1992). They prefer areas with tall trees for nesting UWU The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour (arboreal rooster and nester) but if trees are unavailable, grey herons may roost in dense brush or undergrowth. -

The Grey Heron

Bird Life The Grey Heron t is quite likely that if someone points out a grey heron to you, I you will remember it the next time you see it. The grey heron is a tall bird, usually about 80cm to 1m in height and is common to inland waterways and coasts. Though the grey heron has a loud “fraank” call, it can most often be seen standing silently in shallow water with its long neck outstretched, watching the water for any sign of movement. The grey heron is usually found on its own, although some may feed close together. Their main food is fish, but they will take small mammals, insects, frogs and even young birds. Because of their habit of occasionally taking young birds, herons are not always popular and are often driven away from a feeding area by intensive mobbing. Mobbing is when smaller birds fly aggressively at their predator, in this case the heron, in order to defend their nests or their lives. Like all herons, grey herons breed in a colony called a heronry. They mostly nest in tall trees and bushes, but sometimes they nest on the ground or on ledge of rock by the sea. Nesting starts in February,when the birds perform elaborate displays and make noisy callings. They lay between 3-5 greenish-blue eggs, often stained white by the birds’ droppings. Once hatched, the young © Illustration: Audrey Murphy make continuous squawking noises as they wait to be fed by their parents. And though it doesn’t sound too pleasant, the parent Latin Name: Ardea cinerea swallows the food and brings it up again at the nest, where the Irish Name: Corr réisc young put their bills right inside their parents mouth in order to Colour: Grey back, white head and retrieve it! neck, with a black crest on head. -

Bathymetry and Geomorphology of Shelikof Strait and the Western Gulf of Alaska

geosciences Article Bathymetry and Geomorphology of Shelikof Strait and the Western Gulf of Alaska Mark Zimmermann 1,* , Megan M. Prescott 2 and Peter J. Haeussler 3 1 National Marine Fisheries Service, Alaska Fisheries Science Center, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Seattle, WA 98115, USA 2 Lynker Technologies, Under contract to Alaska Fisheries Science Center, Seattle, WA 98115, USA; [email protected] 3 U.S. Geological Survey, 4210 University Dr., Anchorage, AK 99058, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-206-526-4119 Received: 22 May 2019; Accepted: 19 September 2019; Published: 21 September 2019 Abstract: We defined the bathymetry of Shelikof Strait and the western Gulf of Alaska (WGOA) from the edges of the land masses down to about 7000 m deep in the Aleutian Trench. This map was produced by combining soundings from historical National Ocean Service (NOS) smooth sheets (2.7 million soundings); shallow multibeam and LIDAR (light detection and ranging) data sets from the NOS and others (subsampled to 2.6 million soundings); and deep multibeam (subsampled to 3.3 million soundings), single-beam, and underway files from fisheries research cruises (9.1 million soundings). These legacy smooth sheet data, some over a century old, were the best descriptor of much of the shallower and inshore areas, but they are superseded by the newer multibeam and LIDAR, where available. Much of the offshore area is only mapped by non-hydrographic single-beam and underway files. We combined these disparate data sets by proofing them against their source files, where possible, in an attempt to preserve seafloor features for research purposes. -

Thinking with Birds: Mary Elizabeth Barber's Advocacy for Gender

Thinking with Birds: Mary Elizabeth Barber’s Advocacy for Gender Equality in Ornithology TANJA HAMMEL Department of History, University of Basel This article explores parts of the first South African woman ornithologist’s life and work. It concerns itself with the micro-politics of Mary Elizabeth Barber’s knowledge of birds from the 1860s to the mid-1880s. Her work provides insight into contemporary scientific practices, particularly the importance of cross-cultural collaboration. I foreground how she cultivated a feminist Darwinism in which birds served as corroborative evidence for female selection and how she negotiated gender equality in her ornithological work. She did so by constructing local birdlife as a space of gender equality. While male ornithologists naturalised and reinvigorated Victorian gender roles in their descriptions and depictions of birds, she debunked them and stressed the absence of gendered spheres in bird life. She emphasised the female and male birds’ collaboration and gender equality that she missed in Victorian matrimony, an institution she harshly criticised. Reading her work against the background of her life story shows how her personal experiences as wife and mother as well as her observation of settler society informed her view on birds, and vice versa. Through birds she presented alternative relationships to matrimony. Her protection of insectivorous birds was at the same time an attempt to stress the need for a New Woman, an aspect that has hitherto been overlooked in studies of the transnational anti-plumage -

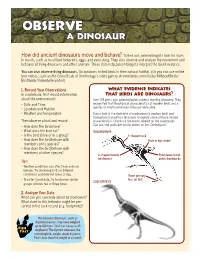

Observebserve a D Dinosaurinosaur

OOBSERVEBSERVE A DDINOSAURINOSAUR How did ancient dinosaurs move and behave? To fi nd out, paleontologists look for clues in fossils, such as fossilized footprints, eggs, and even dung. They also observe and analyze the movement and behavior of living dinosaurs and other animals. These data help paleontologists interpret the fossil evidence. You can also observe living dinosaurs. Go outdoors to fi nd birds in their natural habitat. (Or you can use online bird videos, such as the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s video gallery at www.birds.cornell.edu/AllAboutBirds/ BirdGuide/VideoGallery.html) 1. Record Your Observations What Evidence IndiCates In a notebook, fi rst record information That Birds Are Dinosaurs? about the environment: Over 125 years ago, paleontologists made a startling discovery. They • Date and Time recognized that the physical characteristics of modern birds and a • Location and Habitat species of small carnivorous dinosaur were alike. • Weather and temperature Take a look at the skeletons of roadrunner (a modern bird) and Coelophysis (an extinct dinosaur) to explore some of these shared Then observe a bird and record: characteristics. Check out the bones labeled on the roadrunner. • How does the bird move? Can you fi nd and label similar bones on the Coelophysis? • What does the bird eat? ROADRUNNER • Is the bird alone or in a group? S-shaped neck • How does the bird behave with Hole in hip socket members of its species? • How does the bird behave with members of other species? V-shaped furcula Pubis bone in hip (wishbone) points backwards Tips: • Weather conditions can affect how animals behave. -

Alaska OCS Socioeconomic Studies Program

Technical Report Number 36 Alaska OCS Socioeconomic Studies Program Sponsor: Bureau of Land Management Alaska Outer Northern Gulf of Alaska Petroleum Development Scenarios Sociocultural Impacts The United States Department of the Interior was designated by the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) Lands Act of 1953 to carry out the majority of the Act’s provisions for administering the mineral leasing and develop- ment of offshore areas of the United States under federal jurisdiction. Within the Department, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) has the responsibility to meet requirements of the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA) as well as other legislation and regulations dealing with the effects of offshore development. In Alaska, unique cultural differences and climatic conditions create a need for developing addi- tional socioeconomic and environmental information to improve OCS deci- sion making at all governmental levels. In fulfillment of its federal responsibilities and with an awareness of these additional information needs, the BLM has initiated several investigative programs, one of which is the Alaska OCS Socioeconomic Studies Program (SESP). The Alaska OCS Socioeconomic Studies Program is a multi-year research effort which attempts to predict and evaluate the effects of Alaska OCS Petroleum Development upon the physical, social, and economic environ- ments within the state. The overall methodology is divided into three broad research components. The first component identifies an alterna- tive set of assumptions regarding the location, the nature, and the timing of future petroleum events and related activities. In this component, the program takes into account the particular needs of the petroleum industry and projects the human, technological, economic, and environmental offshore and onshore development requirements of the regional petroleum industry. -

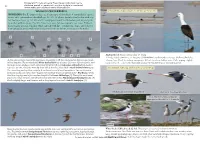

Birds of Chile a Photo Guide

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be 88 distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical 89 means without prior written permission of the publisher. WALKING WATERBIRDS unmistakable, elegant wader; no similar species in Chile SHOREBIRDS For ID purposes there are 3 basic types of shorebirds: 6 ‘unmistakable’ species (avocet, stilt, oystercatchers, sheathbill; pp. 89–91); 13 plovers (mainly visual feeders with stop- start feeding actions; pp. 92–98); and 22 sandpipers (mainly tactile feeders, probing and pick- ing as they walk along; pp. 99–109). Most favor open habitats, typically near water. Different species readily associate together, which can help with ID—compare size, shape, and behavior of an unfamiliar species with other species you know (see below); voice can also be useful. 2 1 5 3 3 3 4 4 7 6 6 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 45–48cm N Andes. Fairly common s. to Atacama (3700–4600m); rarely wanders to coast. Shallow saline lakes, At first glance, these shorebirds might seem impossible to ID, but it helps when different species as- adjacent bogs. Feeds by wading, sweeping its bill side to side in shallow water. Calls: ringing, slightly sociate together. The unmistakable White-backed Stilt left of center (1) is one reference point, and nasal wiek wiek…, and wehk. Ages/sexes similar, but female bill more strongly recurved. the large brown sandpiper with a decurved bill at far left is a Hudsonian Whimbrel (2), another reference for size. Thus, the 4 stocky, short-billed, standing shorebirds = Black-bellied Plovers (3). -

REGUA Bird List July 2020.Xlsx

Birds of REGUA/Aves da REGUA Updated July 2020. The taxonomy and nomenclature follows the Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee, updated June 2015 - based on the checklist of the South American Classification Committee (SACC). Atualizado julho de 2020. A taxonomia e nomenclatura seguem o Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Lista anotada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos, atualizada em junho de 2015 - fundamentada na lista do Comitê de Classificação da América do Sul (SACC). -

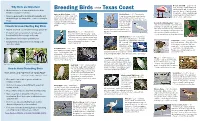

Breeding Birds of the Texas Coast

Roseate Spoonbill • L 32”• Uncom- Why Birds are Important of the mon, declining • Unmistakable pale Breeding Birds Texas Coast pink wading bird with a long bill end- • Bird abundance is an important indicator of the ing in flat “spoon”• Nests on islands health of coastal ecosystems in vegetation • Wades slowly through American White Pelican • L 62” Reddish Egret • L 30”• Threatened in water, sweeping touch-sensitive bill •Common, increasing • Large, white • Revenue generated by hunting, photography, and Texas, decreasing • Dark morph has slate- side to side in search of prey birdwatching helps support the coastal economy in bird with black flight feathers and gray body with reddish breast, neck, and Chuck Tague bright yellow bill and pouch • Nests Texas head; white morph completely white – both in groups on islands with sparse have pink bill with Black-bellied Whistling-Duck vegetation • Preys on small fish in black tip; shaggy- • L 21”• Lo- groups looking plumage cally common, increasing • Goose-like duck Threats to Island-Nesting Bay Birds Chuck Tague with long neck and pink legs, pinkish-red bill, Greg Lavaty • Nests in mixed- species colonies in low vegetation or on black belly, and white eye-ring • Nests in tree • Habitat loss from erosion and wetland degradation cavities • Occasionally nests in mesquite and Brown Pelican • L 51”• Endangered in ground • Uses quick, erratic movements to • Predators such as raccoons, feral hogs, and stir up prey Chuck Tague other woody vegetation on bay islands Texas, but common and increasing • Large -

Waterbirds of Namdapha Tiger Reserve, Arunachal Pradesh with Special Reference to White-Bellied Heron Ardea Insignis

Rec. zool. Surv. India: l08(Part-3) : 109-118, 2008 WATERBIRDS OF NAMDAPHA TIGER RESERVE, ARUNACHAL PRADESH WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO WHITE-BELLIED HERON ARDEA INSIGNIS GOPINATHAN MAHESW ARAN* Zoological Survey of India, M-Block, New Alipore, Kolkata-700 053, India INTRODUCTION Namdapha Tiger Reserve has a rich aquatic bird fauna, mostly because of many freshwater lakes/ponds located at higher altitudes as well as within the evergreen forest patches and the complex river system it has. While surveys were carried out by the research team of the Zoological Survey of India (Ghosh, 1987) from March 1981 to March 1987, the following prominent waterbirds were recorded from Namdapha : Goliath Heron Ardea goliath, Large Egret Casmerodius albus, Chinese Pond Heron Ardeola bacchus, Little Egret Egretta garzetta, Common Merganser Mergus Inerganser, Eastern Marsh Harrier Circus spilonotus, and at least seven species of kingfishers, beside the migrant Common Teal Anas crecca. However, the team did not record any White-bellied Heron. Interestingly, I did not record Goliath Heron during my surveys in two years, which the team did so. The White-bellied Heron Ardea insignis (Family : Ardeidae) is a little known species occurring in swamps, marshes and forests from Nepal through Sikkim, Bhutan and northeast Assam in India to Bangladesh, Arakan and north Bunna (Walters 1976). According to Ali and Ripley (1987), it is a highly endangered species and restricted to undisturbed reed ~eds and marshes in eastern Nepal and the Sikkim terai, Bihar (north of the Ganges river), Bhutan duars to northern Assam, Bangladesh, Arakan and north Burma (= Myanmar). In Assam, it has been reported from Kaziranga National Park (Barua and Sharma 1999), Jamjing and Bordoloni of Dhemaji district (Choudhury 1990, 1992, 1994), Dibru-Saikhowa Wildlife Sanctuary and Biosphere Reserve (Choudhury 1994), Pobitara Wildlife Sanctuary (Choudhury 1996a, Baruah et al.