January 2020.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NH Bird Records

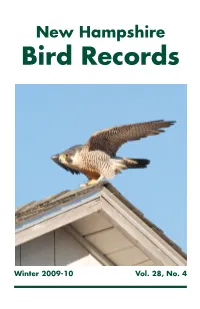

V28 No4-Winter09-10_f 8/22/10 4:45 PM Page i New Hampshire Bird Records Winter 2009-10 Vol. 28, No. 4 V28 No4-Winter09-10_f 8/22/10 4:45 PM Page ii AUDUBON SOCIETY OF NEW HAMPSHIRE New Hampshire Bird Records Volume 28, Number 4 Winter 2009-10 Managing Editor: Rebecca Suomala 603-224-9909 X309, [email protected] Text Editor: Dan Hubbard Season Editors: Pamela Hunt, Spring; Tony Vazzano, Summer; Stephen Mirick, Fall; David Deifik, Winter Layout: Kathy McBride Assistants: Jeannine Ayer, Lynn Edwards, Margot Johnson, Susan MacLeod, Marie Nickerson, Carol Plato, William Taffe, Jean Tasker, Tony Vazzano Photo Quiz: David Donsker Photo Editor: Jon Woolf Web Master: Len Medlock Editorial Team: Phil Brown, Hank Chary, David Deifik, David Donsker, Dan Hubbard, Pam Hunt, Iain MacLeod, Len Medlock, Stephen Mirick, Robert Quinn, Rebecca Suomala, William Taffe, Lance Tanino, Tony Vazzano, Jon Woolf Cover Photo: Peregrine Falcon by Jon Woolf, 12/1/09, Hampton Beach State Park, Hampton, NH. New Hampshire Bird Records is published quarterly by New Hampshire Audubon’s Conservation Department. Bird sight- ings are submitted to NH eBird (www.ebird.org/nh) by many different observers. Records are selected for publication and not all species reported will appear in the issue. The published sightings typically represent the highlights of the season. All records are subject to review by the NH Rare Birds Committee and publication of reports here does not imply future acceptance by the Committee. Please contact the Managing Editor if you would like to report your sightings but are unable to use NH eBird. -

IAGNBI Newsletter 3 July 2004

International Advisory Group for Northern Bald Ibis newsletter 3 July 2004 An update on current projects involving wild and captive Northern Bald Ibis Edited by Christiane Boehm 1. What is IAGNBI ? page 1.1. IAGNBI: Its role and committee 4 1.2. Statement on the conservation priorities 5 2. Ongoing research and release projects: updates of 2003 2.1. The Austrian Bald Ibis Migration 2002-2004: A story of success and failure Johannes Fritz 7 2.2. News from the Gruenau semi-wild colony of the Waldrapp Ibis Kurt Kotrschal 14 2.3. A study of different release techniques for a captive population of Northern Bald Ibis (Geronticus eremita) in the region of La Janda (Cádiz, Southern Spain) Miguel A. Quevedo, Iñigo Sánchez, José M. Aguilar & Mariano Cuadrado 20 2.4. Waldrapp Project „Bschar el Kh-ir“ in Ain Tijja in Morocco Hans Peter Mueller 27 3. Wild colonies: updates of the programmes, situation, projects 3.1. The Bald Ibis in Souss Massa Region ( Morocco) Mohammed El Bekkay, Widade Oubrou 30 3.2. First month of Ibis protection programme 2004 in Syria: never a dull moment… Gianluca Serra 32 4. Meeting reports 4.1 Report on the Northern Bald Ibis Geronticus eremita: Conservation and Reintroduction Workshop, Innsbruck July 2003 Christiane Boehm 34 4.2. Species Action Planning Meetings for the Northern Bald Ibis, Madrid, Spain, January 2004 Species Action Planning Meetings for the Southern Bald Ibis, Wakkastroom, South Africa, November 2003 Chris Bowden 37 4.3. The status of the Northern Bald Ibis within the EAZA Ciconiiformes and Phoenicopteriformes Taxon Advisory Group (TAG) Cathrine King 38 5. -

156 Glossy Ibis

Text and images extracted from Marchant, S. & Higgins, P.J. (co-ordinating editors) 1990. Handbook of Australian, New Zealand & Antarctic Birds. Volume 1, Ratites to ducks; Part B, Australian pelican to ducks. Melbourne, Oxford University Press. Pages 953, 1071-1 078; plate 78. Reproduced with the permission of Bird life Australia and Jeff Davies. 953 Order CICONIIFORMES Medium-sized to huge, long-legged wading birds with well developed hallux or hind toe, and large bill. Variations in shape of bill used for recognition of sub-families. Despite long legs, walk rather than run and escape by flying. Five families of which three (Ardeidae, Ciconiidae, Threskiornithidae) represented in our region; others - Balaenicipitidae (Shoe-billed Stork) and Scopidae (Hammerhead) - monotypic and exclusively Ethiopian. Re lated to Phoenicopteriformes, which sometimes considered as belonging to same order, and, more distantly, to Anseriformes. Behavioural similarities suggest affinities also to Pelecaniformes (van Tets 1965; Meyerriecks 1966), but close relationship not supported by studies of egg-white proteins (Sibley & Ahlquist 1972). Suggested also, mainly on osteological and other anatomical characters, that Ardeidae should be placed in separate order from Ciconiidae and that Cathartidae (New World vultures) should be placed in same order as latter (Ligon 1967). REFERENCES Ligon, J.D. 1967. Occas. Pap. Mus. Zool. Univ. Mich. 651. Sibley, C. G., & J.E. Ahlquist. 1972. Bull. Peabody Mus. nat. Meyerriecks, A.J. 1966. Auk 83: 683-4. Hist. 39. van Tets, G.F. 1965. AOU orn. Monogr. 2. 1071 Family PLATALEIDAE ibises, spoonbills Medium-sized to large wading and terrestial birds. About 30 species in about 15 genera, divided into two sub families: ibises (Threskiornithinae) and spoonbills (Plataleinae); five species in three genera breeding in our region. -

Geronticus Eremita) in Moravia in Gallašʼs Manuscript

ISSN 2336-3193 Acta Mus. Siles. Sci. Natur., 66: 163-165, 2017 DOI: 10.1515/cszma-2017-0019 Published: online 30th October 2017, print November 2017 The Hermit Ibis (Geronticus eremita) in Moravia in Gallašʼs manuscript Jiří J. Hudeček The Hermit Ibis (Geronticus eremita) in Moravia in Gallašʼs manuscript. – Acta Mus. Siles. Sci. Natur., 66: 163-165, 2017. Abstract: J. H. A. Gallaš (1756-1840) mentioned in his manuscript the occurrence of Corvus eremita L. in Moravia. Mlíkovský (2007) says incorrectly that Hudeček & Hanák (2004) had stated in was a discovery from the 19 th century. We have not written anything of this sort. Nevertheless, the author of his text persists on its potential occurrence in the 18 th century. The species Corvus eremita L. (= Geronticus eremita) has been taken as made-up and non-existent since the beginning of the 19 th century but its application in relation to the species Corvus graculus L. (= Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax) was overcome in Europe at the end of the 19 th century. Key words: Geronticus eremita, Corvus eremita L., Moravia, Czech Republic, existence, 18 and 19th century, incorrectly interpreting, historical ornithology Gallašʼs note to Moravian territory The occurrence of the Hermit Ibis (Geronticus eremita (Linnaeus, 1758)) in central Europe reached up to Austria, southern Germany, Hungary, Switzerland and Moravia (for example Bauer & Glutz von Blotzheim 1966). J. H. A. Gallaš (1756-1840), Moravian polymath, military physician and writer (biography see Šmídek 1877, Hanuš 1895, Indra 1931, Kirnerová 2011, Spáčilová 2012) recorded the species Corvus eremita L. in Moravia already in 1822. Present: "inhabit in Smolna (right Smolno) and Radíkov Mountain in local parts" (in present time, Skutil 1936, Hudec et al. -

Web-Book Catalog 2021-05-10

Lehigh Gap Nature Center Library Book Catalog Title Year Author(s) Publisher Keywords Keywords Catalog No. National Geographic, Washington, 100 best pictures. 2001 National Geogrpahic. Photographs. 779 DC Miller, Jeffrey C., and Daniel H. 100 butterflies and moths : portraits from Belknap Press of Harvard University Butterflies - Costa 2007 Janzen, and Winifred Moths - Costa Rica 595.789097286 th tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA rica Hallwachs. Miller, Jeffery C., and Daniel H. 100 caterpillars : portraits from the Belknap Press of Harvard University Caterpillars - Costa 2006 Janzen, and Winifred 595.781 tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA Rica Hallwachs 100 plants to feed the bees : provide a 2016 Lee-Mader, Eric, et al. Storey Publishing, North Adams, MA Bees. Pollination 635.9676 healthy habitat to help pollinators thrive Klots, Alexander B., and Elsie 1001 answers to questions about insects 1961 Grosset & Dunlap, New York, NY Insects 595.7 B. Klots Cruickshank, Allan D., and Dodd, Mead, and Company, New 1001 questions answered about birds 1958 Birds 598 Helen Cruickshank York, NY Currie, Philip J. and Eva B. 101 Questions About Dinosaurs 1996 Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, NY Reptiles Dinosaurs 567.91 Koppelhus Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, N. 101 Questions About the Seashore 1997 Barlowe, Sy Seashore 577.51 Y. Gardening to attract 101 ways to help birds 2006 Erickson, Laura. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA Birds - Conservation. 639.978 birds. Sharpe, Grant, and Wenonah University of Wisconsin Press, 101 wildflowers of Arcadia National Park 1963 581.769909741 Sharpe Madison, WI 1300 real and fanciful animals : from Animals, Mythical in 1998 Merian, Matthaus Dover Publications, Mineola, NY Animals in art 769.432 seventeenth-century engravings. -

IUCN-SSC Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group Special Publication 2

IUCN-SSC Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group Special Publication 2 Proceedings of the IX Workshop of the AEWA Eurasian Spoonbill International Expert Group Djerba Island, Tunisia, 14th - 18th November 2018 Editors: Jocelyn Champagnon, Jelena Kralj, Luis Santiago Cano Alonso and K. S. Gopi Sundar Editors-in-Chief, Special Publications, IUCN-SSC Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group K.S. Gopi Sundar, Co-chair IUCN Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group Luis Santiago Cano Alonso, Co-chair IUCN Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group Invited Editors for this issue Jocelyn Champagnon, Tour du Valat, Research Institute for the Conservation of Mediterranean Wetlands, Arles, France Jelena Kralj, Institute of Ornithology, Zagreb, Croatia Expert Review Board Hichem Azafzaf, Association “les Amis des Oiseaux » (AAO/BirdLife Tunisia), Tunisia Petra de Goeij, Royal NIOZ, the Netherlands Csaba Pigniczki, Kiskunság National Park Directorate, Hungary Suggested citation of this publication: Champagnon J., Kralj J., Cano Alonso, L. S. & Sundar, K. S. G. (ed.) 2019. Proceedings of the IX Workshop of the AEWA Eurasian Spoonbill International Expert Group. IUCN-SSC Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group Special Publication 2. Arles, France. ISBN 978-2-491451-00-4. Recommended Citation of a chapter: Marion L. 2019. Recent trends of the breeding population of Spoonbill in France 2012- 2018. Pp 19- 23. In: Champagnon J., Kralj J., Cano Alonso, L. S. & Sundar, K. S. G. (ed.) Proceedings of the IX Workshop of the AEWA Eurasian Spoonbill International Expert Group. IUCN-SSC Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group Special Publication 2. Arles, France. INFORMATION AND WRITING DISCLAIMER The information and opinions expressed in this publication belong to the authors. -

BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis Mcintosh

COM . TOCK S HUTTER © S © BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis McIntosh For passionate birdwatcher Sandy Komito of over age 16 say they actively observe and try to iden- Fair Lawn, New Jersey, 1998 was a big year. In a tify birds, although few go to the extremes Komito tight competition with two fellow birders to see as did. About 88 percent are content to enjoy bird many species as possible in a single year, Komito watching in their own backyards or neighborhoods. traveled 270,000 miles, crisscrossing North Amer- More avid participants plan vacations around ica and voyaging far out to sea to locate rare and their hobby and sometimes travel long distances to elusive birds. In the end, he set a North American view a rare species and add it to their lifelong list of record of 748 species, topping his own previous birds spotted. Many birdwatchers, both casual and record of 726, which had stood for 11 years. serious, also function as citizen scientists, provid- Komito and his fellow competitors are not alone ing valuable data to help scientists monitor bird in their love of birds. According to a U.S. Fish and populations and create management guidelines to Wildlife Service survey, about one in five Americans protect species in decline. 36 2 0 1 4 N UMBER 1 | E NGLISH T E ACHING F ORUM Birding Basics The origins of bird watching in the United States date back to the late 1800s when conserva- tionists became concerned about the hunting of birds to supply feathers for the fashion industry. -

2016 LBRC Newsletter

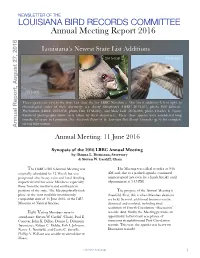

NEWSLETTER OF THE LOUISIANA BIRD RECORDS COMMITTEE Annual Meeting Report 2016 Louisiana’s Newest State List Additions 2015-058 2016-003 August 27, 2016 2014-031 Three species are new to the State List since the last LBRC Newsletter. Our latest additions (left to right, in chronological order of their discovery) are: Sooty Shearwater (LBRC 2014-031, photo Will Selman), Pyrrhuloxia (LBRC 2015-058, photo Dan O’Malley), and Mew Gull (2016-003, photo Charles E. Lyon). Excellent photographs above were taken by their discoverers. These three species were considered long overdue to occur in Louisiana. See Nineteenth Report of the Louisiana Bird Records Committee (p. 6) for complete record information. Annual Report, Annual Meeting: 11 June 2016 Synopsis of the 2016 LBRC Annual Meeting by: Donna L. Dittmann, Secretary & Steven W. Cardiff, Chair The LBRC’s 2016 Annual Meeting was The Meeting was called to order at 9:56 originally scheduled for 12 March but was AM and, due to a packed agenda, continued postponed after heavy rains and local flooding uninterrupted (not even for a lunch break!) until impacted travel for some Members, especially adjournment at 5:45 PM. those from the northern and southeastern portions of the state. The Meeting finally took The purpose of the Annual Meeting is place on the next available unanimously threefold. First, this is when Member elections compatible date of 11 June 2016, at the LSU are held. Second, additional business can be Museum of Natural Science. discussed and resolved, including final resolution of Fourth Circulation “Discussion” Eight Voting Members were in records. -

Theristicus Caudatus;Argentina

The Condor96:99&1002 Q The cooper omith&gical society1994 BREEDING PERFORMANCE IN RELATION TO NEST-SITE SUBSTRATUM IN A BUFF-NECKED IBIS (THHWTICUS CA UDATUS) POPULATION IN PATAGONIA ’ Jose A. DONAZAR Estacidn Biologica de Doiiana, CSIC, Avda I%@Luisa s.n., 41013 Sevilla, Spain OLGA CEBALL~S Grupo de EstudiosBiologicos Ugarra, Carlos III 19, 31002 Pamplona, Spain ALEJANDRO TRAVAINI AND ALFJANDRO RODRIGUEZ EstacirinBiologica de Doiiana, CSIC Avda M Luisa s.n., 41013 Sevilla, Spain MARTIN FUNES Centro de Ecologia Aplicada de1Neuquen, Casilla de Correos92, 8371 Junin de 10sAndes, Neuquen, Argentina FERNANDO HIRAL~ Estacion Biologicade Dofiana, CSIC Avda M Luisa sn., 41013 Sevilla, Spain Abstract. In northern Argentinean Patagonia, Buff-necked Ibis (Theristicuscaudatus) nest on different substrata:cliffs, trees, and marsh vegetation. According to the ideal-free distribution hypothesis,this polymorphism may be due to the occupationofthe bestbreeding habitats by dominant individuals and the relegation of the subdominant birds to marginal substratawith a lower probability of achieving successfulbreeding. We investigatedwhether there were any variations in the breeding performance among colonies and whether these variations were related to the breeding substratum.Laying date varied from the third week of September to the last week of October, laying occurring earlier in colonies at lower elevations. Clutch size per colony varied between 1.8 and 2.0 (X 1.9, n = 106), but significant differences were not detected among colonies. Brood size per colony varied significantly, rangingbetween 1.3 and 2.0 (52= 1.8, n = 164). The substratumof breedingdid not influence variations in any of these three parameters. The physical condition of the chicks did not vary among substrata,but there was inter-colony variation in broods of two chicks. -

Satellite Tracking Reveals the Migration Route and Wintering Area of the Middle East Population of Critically Endangered Northern Bald Ibis Geronticus Eremita

Satellite tracking reveals the migration route and wintering area of the Middle East population of Critically Endangered northern bald ibis Geronticus eremita J eremy A. Lindsell,Gianluca S erra,Lubomir P ESˇ KE,Mahmoud S. Abdullah G hazy al Q aim,Ahmed K anani and M engistu W ondafrash Abstract Since its discovery in 2002 the small colony of coastline in Morocco now subject to intensive conservation northern bald ibis Geronticus eremita in the central Syrian management. A Middle Eastern population was thought desert remains at perilously low numbers, despite good extinct since 1989 (Arihan, 1998), and extinct in Syria since productivity and some protection at their breeding grounds. the late 1920s (Safriel, 1980), part of a broad long-term The Syrian birds are migratory and return rates of young decline in this species (Kumerloeve, 1984). Unlike the birds appear to have been poor but because the migration relatively sedentary Moroccan birds, the eastern population route and wintering sites were unknown little could be was migratory (Hirsch, 1979) but the migration routes and done to address any problems away from Syria. Satellite wintering sites were unknown. The discovery of a colony of tracking of three adult birds in 2006–2007 has shown they northern bald ibises in Syria in 2002 (Serra et al., 2003) migrate through Jordan, Saudi Arabia and Yemen to the confirmed the survival of this migratory population. The central highlands of Ethiopia. The three tagged birds and Syrian birds arrive in the breeding area in February and one other adult were found at the wintering site but none depart in July. -

Behavioural Adaptation of a Bird from Transient Wetland Specialist to an Urban Resident

Behavioural Adaptation of a Bird from Transient Wetland Specialist to an Urban Resident John Martin1,2*, Kris French1, Richard Major2 1 Institute for Conservation Biology and Environmental Management, School of Biological Sciences, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, New South Wales, Australia, 2 Terrestrial Ecology, Australian Museum, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia Abstract Dramatic population increases of the native white ibis in urban areas have resulted in their classification as a nuisance species. In response to community and industry complaints, land managers have attempted to deter the growing population by destroying ibis nests and eggs over the last twenty years. However, our understanding of ibis ecology is poor and a question of particular importance for management is whether ibis show sufficient site fidelity to justify site-level management of nuisance populations. Ibis in non-urban areas have been observed to be highly transient and capable of moving hundreds of kilometres. In urban areas the population has been observed to vary seasonally, but at some sites ibis are always observed and are thought to be behaving as residents. To measure the level of site fidelity, we colour banded 93 adult ibis at an urban park and conducted 3-day surveys each fortnight over one year, then each quarter over four years. From the quarterly data, the first year resighting rate was 89% for females (n = 59) and 76% for males (n = 34); this decreased to 41% of females and 21% of males in the fourth year. Ibis are known to be highly mobile, and 70% of females and 77% of males were observed at additional sites within the surrounding region (up to 50 km distant). -

Roseate Spoonbill Breeding in Camden County: a First State Nesting Record for Georgia

vol. 76 • 3 – 4 THE ORIOLE 65 ROSEATE SPOONBILL BREEDING IN CAMDEN COUNTY: A FIRST STATE NESTING RECORD FOR GEORGIA Timothy Keyes One Conservation Way Brunswick, GA 31520 [email protected] Chris Depkin One Conservation Way Brunswick, GA 31520 [email protected] Jessica Aldridge 6222 Charlie Smith Sr. Hwy St. Marys, GA 31558 [email protected] Introduction We report the northernmost breeding record of Roseate Spoonbill (Platalea ajaja) on the Atlantic Coast of the U.S. Nesting activity has been suspected in Georgia for at least 5 years, but was first confirmed in June 2011 at a large wading bird colony in St. Marys, Camden County, Georgia. Prior to this record, the furthest northern breeding record for Roseate Spoonbill was in St. Augustine, St. John’s County, Florida, approximately 100 km to the south. This record for Georgia continues a trend of northward expansion of Roseate Spoonbill post-breeding dispersal and breeding ranges. Prior to the plume-hunting era of the mid to late 1800s, the eastern population of Roseate Spoonbill was more abundant and widespread than it is today (Dumas 2000), breeding across much of south Florida. Direct persecution and collateral disturbance by egret plume hunters led to a significant range contraction between 1850 and the 1890s (Allen 1942), limiting the eastern population of Roseate Spoonbills to a few sites in Florida Bay by the 1940s. A low of 15 nesting pairs were documented in 1936 (Powell et al. 1989). By the late 1960s, Roseate Spoonbills began to expand out of Florida Bay, slowly reclaiming some of the territory they had lost.