Trapping White Ibises with Rocket Nets and Mist Nets in the Florida Everglades

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 2020.Indd

BROWN PELICAN Photo by Rob Swindell at Melbourne, Florida JANUARY 2020 Editors: Jim Jablonski, Marty Ackermann, Tammy Martin, Cathy Priebe Webmistress: Arlene Lengyel January 2020 Program Tuesday, January 7, 2020, 7 p.m. Carlisle Reservation Visitor Center Gulls 101 Chuck Slusarczyk, Jr. "I'm happy to be presenting my program Gulls 101 to the good people of Black River Audubon. Gulls are notoriously difficult to identify, but I hope to at least get you looking at them a little closer. Even though I know a bit about them, I'm far from an expert in the field and there is always more to learn. The challenge is to know the particular field marks that are most important, and familiarization with the many plumage cycles helps a lot too. No one will come out of this presentation an expert, but I hope that I can at least give you an idea what to look for. At the very least, I hope you enjoy the photos. Looking forward to seeing everyone there!” Chuck Slusarczyk is an avid member of the Ohio birding community, and his efforts to assist and educate novice birders via social media are well known, yet he is the first to admit that one never stops learning. He has presented a number of programs to Black River Audubon, always drawing a large, appreciative gathering. 2019 Wellington Area Christmas Bird Count The Wellington-area CBC will take place Saturday, December 28, 2019. Meet at the McDonald’s on Rt. 58 at 8:00 a.m. The leader is Paul Sherwood. -

And Wildlife, 1928-72

Bibliography of Research Publications of the U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, 1928-72 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF SPORT FISHERIES AND WILDLIFE RESOURCE PUBLICATION 120 BIBLIOGRAPHY OF RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS OF THE U.S. BUREAU OF SPORT FISHERIES AND WILDLIFE, 1928-72 Edited by Paul H. Eschmeyer, Division of Fishery Research Van T. Harris, Division of Wildlife Research Resource Publication 120 Published by the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife Washington, B.C. 1974 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Eschmeyer, Paul Henry, 1916 Bibliography of research publications of the U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, 1928-72. (Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife. Kesource publication 120) Supt. of Docs. no.: 1.49.66:120 1. Fishes Bibliography. 2. Game and game-birds Bibliography. 3. Fish-culture Bibliography. 4. Fishery management Bibliogra phy. 5. Wildlife management Bibliography. I. Harris, Van Thomas, 1915- joint author. II. United States. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife. III. Title. IV. Series: United States Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife. Resource publication 120. S914.A3 no. 120 [Z7996.F5] 639'.9'08s [016.639*9] 74-8411 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing OfTie Washington, D.C. Price $2.30 Stock Number 2410-00366 BIBLIOGRAPHY OF RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS OF THE U.S. BUREAU OF SPORT FISHERIES AND WILDLIFE, 1928-72 INTRODUCTION This bibliography comprises publications in fishery and wildlife research au thored or coauthored by research scientists of the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife and certain predecessor agencies. Separate lists, arranged alphabetically by author, are given for each of 17 fishery research and 6 wildlife research labora tories, stations, investigations, or centers. -

Thinking with Birds: Mary Elizabeth Barber's Advocacy for Gender

Thinking with Birds: Mary Elizabeth Barber’s Advocacy for Gender Equality in Ornithology TANJA HAMMEL Department of History, University of Basel This article explores parts of the first South African woman ornithologist’s life and work. It concerns itself with the micro-politics of Mary Elizabeth Barber’s knowledge of birds from the 1860s to the mid-1880s. Her work provides insight into contemporary scientific practices, particularly the importance of cross-cultural collaboration. I foreground how she cultivated a feminist Darwinism in which birds served as corroborative evidence for female selection and how she negotiated gender equality in her ornithological work. She did so by constructing local birdlife as a space of gender equality. While male ornithologists naturalised and reinvigorated Victorian gender roles in their descriptions and depictions of birds, she debunked them and stressed the absence of gendered spheres in bird life. She emphasised the female and male birds’ collaboration and gender equality that she missed in Victorian matrimony, an institution she harshly criticised. Reading her work against the background of her life story shows how her personal experiences as wife and mother as well as her observation of settler society informed her view on birds, and vice versa. Through birds she presented alternative relationships to matrimony. Her protection of insectivorous birds was at the same time an attempt to stress the need for a New Woman, an aspect that has hitherto been overlooked in studies of the transnational anti-plumage -

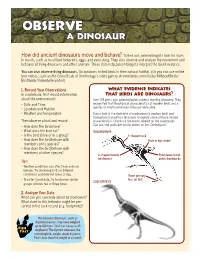

Observebserve a D Dinosaurinosaur

OOBSERVEBSERVE A DDINOSAURINOSAUR How did ancient dinosaurs move and behave? To fi nd out, paleontologists look for clues in fossils, such as fossilized footprints, eggs, and even dung. They also observe and analyze the movement and behavior of living dinosaurs and other animals. These data help paleontologists interpret the fossil evidence. You can also observe living dinosaurs. Go outdoors to fi nd birds in their natural habitat. (Or you can use online bird videos, such as the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s video gallery at www.birds.cornell.edu/AllAboutBirds/ BirdGuide/VideoGallery.html) 1. Record Your Observations What Evidence IndiCates In a notebook, fi rst record information That Birds Are Dinosaurs? about the environment: Over 125 years ago, paleontologists made a startling discovery. They • Date and Time recognized that the physical characteristics of modern birds and a • Location and Habitat species of small carnivorous dinosaur were alike. • Weather and temperature Take a look at the skeletons of roadrunner (a modern bird) and Coelophysis (an extinct dinosaur) to explore some of these shared Then observe a bird and record: characteristics. Check out the bones labeled on the roadrunner. • How does the bird move? Can you fi nd and label similar bones on the Coelophysis? • What does the bird eat? ROADRUNNER • Is the bird alone or in a group? S-shaped neck • How does the bird behave with Hole in hip socket members of its species? • How does the bird behave with members of other species? V-shaped furcula Pubis bone in hip (wishbone) points backwards Tips: • Weather conditions can affect how animals behave. -

Guidelines to the Use of Wild Birds in Research

THE ORNITHOLOGICAL COUNCIL Providing Scientific Information about Birds GUIDELINES TO THE USE OF WILD BIRDS IN RESEARCH Special Publication 1997 Edited by Abbot S. Gaunt & Lewis W. Oring Third Edition 2010 Edited by Jeanne M. Fair, Editor-in-Chief Ellen Paul & Jason Jones, Associate Editors GUIDELINES TO THE USE OF WILD BIRDS IN RESEARCH Jeanne M. Fair1, Ellen Paul2, & Jason Jones3, Anne Barrett Clark4, Clara Davie4, Gary Kaiser5 1 Los Alamos National Laboratory, Atmospheric, Climate and Environmental Dynamics, MS J495, Los Alamos, NM 87506 2 Ornithological Council, 1107 17th St., N.W., Suite 250, Washington, D.C. 20036 3 Tetra Tech EC, 133 Federal Street, 6th floor, Boston, Massachusetts 02110 4 Binghamton University State University of New York, Department of Biology, PO BOX 6000 Binghamton, NY 13902-6000 5 402-3255 Glasgow Ave, Victoria, BC V8X 4S4, Canada Copyright 1997, 2010 by THE ORNITHOLOGICAL COUNCIL 1107 17th Street, N.W. Suite 250 Washington, D.C. 20036 http://www.nmnh.si.edu/BIRDNET Suggested citation Fair, J., E. Paul, and J. Jones, Eds. 2010. Guidelines to the Use of Wild Birds in Research. Washington, D.C.: Ornithological Council. Revision date August 2010 2 Dedication The Ornithological Council dedicates this 2010 revision to Lewis W. Oring and the late Abbot (Toby) S. Gaunt, whose commitment to the well-being of the birds for whom ornithologists share a deep and abiding concern has served our profession well for so many years. Toby Gaunt Lew Oring Revision date August 2010 3 Acknowledgments and disclaimer Third edition The Ornithological Council thanks the Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare of the National Institutes of Health for their financial support for the production of this revision. -

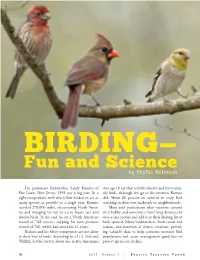

BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis Mcintosh

COM . TOCK S HUTTER © S © BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis McIntosh For passionate birdwatcher Sandy Komito of over age 16 say they actively observe and try to iden- Fair Lawn, New Jersey, 1998 was a big year. In a tify birds, although few go to the extremes Komito tight competition with two fellow birders to see as did. About 88 percent are content to enjoy bird many species as possible in a single year, Komito watching in their own backyards or neighborhoods. traveled 270,000 miles, crisscrossing North Amer- More avid participants plan vacations around ica and voyaging far out to sea to locate rare and their hobby and sometimes travel long distances to elusive birds. In the end, he set a North American view a rare species and add it to their lifelong list of record of 748 species, topping his own previous birds spotted. Many birdwatchers, both casual and record of 726, which had stood for 11 years. serious, also function as citizen scientists, provid- Komito and his fellow competitors are not alone ing valuable data to help scientists monitor bird in their love of birds. According to a U.S. Fish and populations and create management guidelines to Wildlife Service survey, about one in five Americans protect species in decline. 36 2 0 1 4 N UMBER 1 | E NGLISH T E ACHING F ORUM Birding Basics The origins of bird watching in the United States date back to the late 1800s when conserva- tionists became concerned about the hunting of birds to supply feathers for the fashion industry. -

AN EVALUATION of TECHNIQUES for CAPTURING RAPTORS in EAST-CENTRAL MINNESOTA by Mark R

AN EVALUATION OF TECHNIQUES FOR CAPTURING RAPTORS IN EAST-CENTRAL MINNESOTA by Mark R. Fuller and Glenn S. Christenson Department of Ecologyand BehavioralBiology University of Minnesota 310 Biological SciencesCenter St. Paul, Minnesota 55108 ABSTRACT. To meet the objectivesof a study,several species of raptorshad to be trapped on a 9,880-hectare study area of heterogenoushabitat types. Bal-chatri,mist net, Swedish Goshawk,and automatic bow-net traps (and combinationsof these traps) were used in severalgeneral habitat situations.Mist nets combined with a baited bal-chatri or tethered bait were most successfulin capturingbirds, and the bal-chatrisalone and mist nets alone were next most effective. Trappingwas found to be most productivein deciduousupland habitats where an openingin the canopy or break in the understoryoccurred. Trapping along a woodlot-fieldedge was also effective. Strigiformeswere most often trappedjust before sunriseor just after sunset,while falconiformeswere most often capturedin the late morning and late afternoon. Trapping was least efficient from Decemberto February. A different trap type from that i•sedin the initial captureis often most effectivefor recaptur- ing raptors.Maintenance of healthybait animalsand frequent trap checksare emphasized. Introduction This paperpresents results from a combinationof methodsused to captureand recapture Great HornedOwls (Bubo virginianus), Barred Owls (Strix varia),Red-tailed Hawks (Buteo }amaicensis),and Broad-wingedHawks (Buteo platypterus) on a 9,880-hectarestudy area in east-central -

Beginning Birdwatching 2021 Resource List

Beginning Birdwatching 2021 Resource List Field Guides and how-to Birds of Illinois-Sheryl Devore and Steve Bailey The New Birder’s Guide to Birds of North America-Bill Thompson III Sibley’s Birding Basics-David Sibley Peterson Guide to Bird Identification-in 12 Steps-Howell and Sullivan Clubs and Organizations Chicago Ornithological Society-www.chicagobirder.org DuPage Birding Club-www.dupagebirding.org Evanston-North Shore Bird Club-www.ensbc.org Illinois Audubon Society-www.illinoisaudubon.org Will, Kane, Lake Cook county Audubon chapters (and others in Illinois) Illinois Ornithological Society-www.illinoisbirds.org Illinois Young Birders-(ages 9-18) monthly field trips and yearly symposiums Wild Things Conference 2021 American Birding Association- aba.org On-line Resources Cornell Lab of Ornithology All About Birds, eBird, Birdcast Radar, Macaulay Library (sounds), Youtube series: Inside Birding: Shape, Habitat, Behavior DuPage Birding Club-Youtube channel, Mini-tutorials, Bird-O-Bingo card, DuPage hot spot descriptions Facebook: Illinois Birding Network, Illinois Rare Bird Alert, World Girl Birders, Raptor ID, What’s this Bird? Birdnote-can subscribe for informative, weekly emails-also Podcast Birdwatcher’s Digest podcasts: Out There With the Birds, Birdsense Podcasts: Laura Erickson’s For the Birds, Ray Brown’s Talkin’ Birds, American Birding Podcast (ABA) Blog: Jeff Reiter’s “Words on Birds” (meet Jeff on his monthly walks at Cantigny, see DuPage Birding Club website for schedule) Illinois Birding by County-countywiki.ilbirds.com -

Filed Techniques-Bats

Expedition Field Techniques BATS Kate Barlow Geography Outdoors: the centre supporting field research, exploration and outdoor learning Royal Geographical Society with IBG 1 Kensington Gore London SW7 2AR Tel +44 (0)20 7591 3030 Fax +44 (0)20 7591 3031 Email [email protected] Website www.rgs.org/go October 1999 ISBN 978-0-907649-82-3 Cover illustration: A Noctilio leporinus mist-netted during an expedition, FFI Montserrat Biodiversity Project 1995, by Dave Fawcett. Courtesy of Kate Jones, and taken from the cover of her thesis entitled ‘Evolution of bat life histories’, University of Surrey. Expedition Field Techniques BATS CONTENTS Acknowledgements Preface Section One: Bats and Fieldwork 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Literature Reviews 3 1.3 Licences 3 1.4 Health and Safety 4 1.4.1 Hazards associated with bats 5 1.5 Ethics 6 1.6 Project Planning 6 Section Two: Capture Techniques 8 2.1 Introduction 8 2.2 Catching bats 8 2.2.1 Mist-nets 8 2.2.2 Mist-net placement 10 2.2.3 Harp-traps 12 2.2.4 Harp-trap placement 13 2.2.5 Comparison of mist-net and harp-traps 13 2.2.6 Hand-netting for bats 14 2.3 Sampling for bats 14 Section Three: Survey Techniques 18 3.1 Introduction 18 3.2 Surveys at roosts 18 3.2.1 Emergence counts 18 3.2.2 Roost counts 19 3.3 Population estimates 20 Expedition Field Techniques Section Four: Processing Bats 22 4.1 Handling bats 22 4.1.1 Removing bats from mist-nets 22 4.1.2 Handling bats 24 4.2 Assessment of age and reproductive status 25 4.3 Measuring bats 26 4.4 Identification 28 4.5 Data recording 29 Section Five: Specimen Preparation -

Chapter 3. Capture and Marking

CHAPTER 3. CAPTURE AND MARKING A. Overview Scientific studies of birds often require that birds be captured to gather morphometric data and to collect samples for pathological, genetic, and biogeochemical analysis. These data and samples can be used to understand evolutionary relationships, genetics, population structure and dynamics, comparative anatomy and physiology, adaptation, behavior, parasites and diseases, geographic distributions, migration, and the general ecology of wild populations of birds. This knowledge informs us about avian biology and natural history and is necessary to effect science-based conservation and management policies for game and non-game species, endangered species, economically important species, and bird habitat conservation (White and Garrott 1990). Capture is generally necessary to mark birds, which allows scientists to investigate demography, migration/movement patterns, or identify specific individuals after release (Day et al. 1980). Many techniques have been developed to capture and mark birds (Nietfeld et al. 1994; Bub 1995). The assumption that marking does not affect the birds is critical because it is the basis for generalizing the data to unmarked birds (Murray and Fuller 2000). The purpose of this section is not to describe capture and marking techniques, but instead to discuss the effects that different capture and marking techniques have on a bird’s short- and long-term physiological well-being and survival. The more commonly used methods are covered and described briefly, but the focus is on the potential impacts of the method. Thus, even if a particular method is not covered, the researcher is alerted to concerns that may arise and questions to be considered in refining methods so as to reduce impacts. -

NFBB Vol. 32 1957

Howard L. Cogswell, Mills College, Oakland, Calif. Russel H. Pray, 662 Santa Rosa Ave., Berkeley, Calif. William K. Kirsher, .571 Fulton Ave., Sacramento, Calif. Lillian Henningson, 124 Cambridge Way, Piedmont, Calif. Address contributions for the N~VS to William K. Kirsher, F~itor-- .571 Fulton Avenue Sacramento 2.5, California PAGE EIGHTEEN THOUSAND AND FOUR CLIFF SWALLOWS by William K. Kirsher. 1 MIST NETS LEGALIZED IN CALIFORNIA. • . 4 MIST NET SUPPLIERS . • . • . • . 6 GULL BANDING IN THE KI~~TH by Carl Richardson • 7 NEVlS FROM TIIEBANDERS. 9 CHAPTER NOTES. • • • . • . • . • 10 EIGHTEEN THOUSAND AND FOUR CLIFF SWALLOWS b:{William K. Kirsher In the flat agricultural lands around Sacramento, California where in prlml- tive times Cliff swallows (petrochelidon p;trrhonota) must have been hard put to find nesting sites, today there are man-made structures that admirably fill the bird's needs for sheltered, elevated purchases for their mud nests. The species now populates the valley abundantly. Colonies are often found in culverts and under small bridges, some no higher than a man's head. In these, by working at night when all the birds are at the nest, practically the whole colony can be trapped by simultaneously closing both openings of the structure with large fish nets. Most of the m,allows flush at the first disturbance, fluttering to the nets where they are easily captured by hand. There are always a few reluctant ones that have to be flushed by shining a bright light (which the bander wears on his forehead) into the nest as he claps his hands and makes hissing sounds and other noises. -

Ment for Advanoed Ornithology (Zoology 119) at the University of Michigan Biological Station, Cheboygan, Michigan

THE LIFE HISTORY THE RUBY-THROATED HUMBBIHGBIRD .by -- J, Reuben Sandve Minneapolis, Minnesota A report of an original field study conduotsd aa a require- ment for Advanoed Ornithology (Zoology 119) at the University of Michigan Biological Station, Cheboygan, Michigan. +4 f q3 During the summer of 1943 while at the Univereity of Michigan Biological Station in Cheboygam County, Michigan, I was afforded fhe opportunity of making eon8 observations- - on the nesting habits of the Ruby-throated Hummingbird (Archl- lochue colubrie). Observations were carried on far a two week period starting July 7 when a nest with two young waa . discovered and terminating on July 21, on whloh day the young left the nest. Although obeerrafions on a number of nests would have been more satiefaotory, no attempt was mMe to find additional nests both because of the latenese of the seaeon and the unlikehihood of finding any withln the Station area. The purpoae of this study has been to gain further in- formation on a necessarily limited phase of the life hlstory of the Ruby-throated Hummingbird which would contribute 1,n a emall way to a better understanding of its habite and behavior. Observations were made almoet exclusively from a tower blind whose floor was located four feet from the nest. A limited amount of observation was done outside of the blind with a pair of eight power binoculars. I -Nest The nest waa located in a small Whlte Birch (Betula -alba) about 22 feet from the ground and plaoed four feet out on a limb which was one-half Inch in diameter, It