Filed Techniques-Bats

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And Wildlife, 1928-72

Bibliography of Research Publications of the U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, 1928-72 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF SPORT FISHERIES AND WILDLIFE RESOURCE PUBLICATION 120 BIBLIOGRAPHY OF RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS OF THE U.S. BUREAU OF SPORT FISHERIES AND WILDLIFE, 1928-72 Edited by Paul H. Eschmeyer, Division of Fishery Research Van T. Harris, Division of Wildlife Research Resource Publication 120 Published by the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife Washington, B.C. 1974 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Eschmeyer, Paul Henry, 1916 Bibliography of research publications of the U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, 1928-72. (Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife. Kesource publication 120) Supt. of Docs. no.: 1.49.66:120 1. Fishes Bibliography. 2. Game and game-birds Bibliography. 3. Fish-culture Bibliography. 4. Fishery management Bibliogra phy. 5. Wildlife management Bibliography. I. Harris, Van Thomas, 1915- joint author. II. United States. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife. III. Title. IV. Series: United States Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife. Resource publication 120. S914.A3 no. 120 [Z7996.F5] 639'.9'08s [016.639*9] 74-8411 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing OfTie Washington, D.C. Price $2.30 Stock Number 2410-00366 BIBLIOGRAPHY OF RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS OF THE U.S. BUREAU OF SPORT FISHERIES AND WILDLIFE, 1928-72 INTRODUCTION This bibliography comprises publications in fishery and wildlife research au thored or coauthored by research scientists of the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife and certain predecessor agencies. Separate lists, arranged alphabetically by author, are given for each of 17 fishery research and 6 wildlife research labora tories, stations, investigations, or centers. -

Diet and the Evolution of Digestion and Renal Function in Phyllostomid Bats

Zoology 104 (2001): 59–73 © by Urban & Fischer Verlag http://www.urbanfischer.de/journals/zoology Diet and the evolution of digestion and renal function in phyllostomid bats Jorge E. Schondube1,*, L. Gerardo Herrera-M.2 and Carlos Martínez del Rio1 1Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Arizona, Tucson 2Instituto de Biología, Departamento de Zoología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México Received: April 2, 2001 · Accepted: April 12, 2001 Abstract Bat species in the monophyletic family Phyllostomidae feed on blood, insects, small vertebrates, nectar, fruit and complex omnivorous mixtures. We used nitrogen stable isotope ratios to characterize bat diets and adopted a phylogenetically informed approach to investi- gate the physiological changes that accompany evolutionary diet changes in phyllostomids. We found that nitrogen stable isotopes sep- arated plant-eating from animal-eating species. The blood of the latter was enriched in 15N. A recent phylogenetic hypothesis suggests that with the possible exception of carnivory, which may have evolved twice, all diets evolved only once from insectivory. The shift from insectivory to nectarivory and frugivory was accompanied by increased intestinal sucrase and maltase activity, decreased trehalase activity, and reduced relative medullary thickness of kidneys. The shift from insectivory to sanguinivory and carnivory resulted in re- duced trehalase activity. Vampire bats are the only known vertebrates that do not exhibit intestinal maltase activity. We argue that these physiological changes are adaptive responses to evolutionary diet shifts. Key words: Bats, comparative method, diet, digestive and renal function, stable isotopes. Introduction The family Phyllostomidae is a speciose (49 genera and Characterizing animal diets can be difficult. -

Guidelines to the Use of Wild Birds in Research

THE ORNITHOLOGICAL COUNCIL Providing Scientific Information about Birds GUIDELINES TO THE USE OF WILD BIRDS IN RESEARCH Special Publication 1997 Edited by Abbot S. Gaunt & Lewis W. Oring Third Edition 2010 Edited by Jeanne M. Fair, Editor-in-Chief Ellen Paul & Jason Jones, Associate Editors GUIDELINES TO THE USE OF WILD BIRDS IN RESEARCH Jeanne M. Fair1, Ellen Paul2, & Jason Jones3, Anne Barrett Clark4, Clara Davie4, Gary Kaiser5 1 Los Alamos National Laboratory, Atmospheric, Climate and Environmental Dynamics, MS J495, Los Alamos, NM 87506 2 Ornithological Council, 1107 17th St., N.W., Suite 250, Washington, D.C. 20036 3 Tetra Tech EC, 133 Federal Street, 6th floor, Boston, Massachusetts 02110 4 Binghamton University State University of New York, Department of Biology, PO BOX 6000 Binghamton, NY 13902-6000 5 402-3255 Glasgow Ave, Victoria, BC V8X 4S4, Canada Copyright 1997, 2010 by THE ORNITHOLOGICAL COUNCIL 1107 17th Street, N.W. Suite 250 Washington, D.C. 20036 http://www.nmnh.si.edu/BIRDNET Suggested citation Fair, J., E. Paul, and J. Jones, Eds. 2010. Guidelines to the Use of Wild Birds in Research. Washington, D.C.: Ornithological Council. Revision date August 2010 2 Dedication The Ornithological Council dedicates this 2010 revision to Lewis W. Oring and the late Abbot (Toby) S. Gaunt, whose commitment to the well-being of the birds for whom ornithologists share a deep and abiding concern has served our profession well for so many years. Toby Gaunt Lew Oring Revision date August 2010 3 Acknowledgments and disclaimer Third edition The Ornithological Council thanks the Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare of the National Institutes of Health for their financial support for the production of this revision. -

AN EVALUATION of TECHNIQUES for CAPTURING RAPTORS in EAST-CENTRAL MINNESOTA by Mark R

AN EVALUATION OF TECHNIQUES FOR CAPTURING RAPTORS IN EAST-CENTRAL MINNESOTA by Mark R. Fuller and Glenn S. Christenson Department of Ecologyand BehavioralBiology University of Minnesota 310 Biological SciencesCenter St. Paul, Minnesota 55108 ABSTRACT. To meet the objectivesof a study,several species of raptorshad to be trapped on a 9,880-hectare study area of heterogenoushabitat types. Bal-chatri,mist net, Swedish Goshawk,and automatic bow-net traps (and combinationsof these traps) were used in severalgeneral habitat situations.Mist nets combined with a baited bal-chatri or tethered bait were most successfulin capturingbirds, and the bal-chatrisalone and mist nets alone were next most effective. Trappingwas found to be most productivein deciduousupland habitats where an openingin the canopy or break in the understoryoccurred. Trapping along a woodlot-fieldedge was also effective. Strigiformeswere most often trappedjust before sunriseor just after sunset,while falconiformeswere most often capturedin the late morning and late afternoon. Trapping was least efficient from Decemberto February. A different trap type from that i•sedin the initial captureis often most effectivefor recaptur- ing raptors.Maintenance of healthybait animalsand frequent trap checksare emphasized. Introduction This paperpresents results from a combinationof methodsused to captureand recapture Great HornedOwls (Bubo virginianus), Barred Owls (Strix varia),Red-tailed Hawks (Buteo }amaicensis),and Broad-wingedHawks (Buteo platypterus) on a 9,880-hectarestudy area in east-central -

BATS of the Golfo Dulce Region, Costa Rica

MURCIÉLAGOS de la región del Golfo Dulce, Puntarenas, Costa Rica BATS of the Golfo Dulce Region, Costa Rica 1 Elène Haave-Audet1,2, Gloriana Chaverri3,4, Doris Audet2, Manuel Sánchez1, Andrew Whitworth1 1Osa Conservation, 2University of Alberta, 3Universidad de Costa Rica, 4Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute Photos: Doris Audet (DA), Joxerra Aihartza (JA), Gloriana Chaverri (GC), Sébastien Puechmaille (SP), Manuel Sánchez (MS). Map: Hellen Solís, Universidad de Costa Rica © Elène Haave-Audet [[email protected]] and other authors. Thanks to: Osa Conservation and the Bobolink Foundation. [fieldguides.fieldmuseum.org] [1209] version 1 11/2019 The Golfo Dulce region is comprised of old and secondary growth seasonally wet tropical forest. This guide includes representative species from all families encountered in the lowlands (< 400 masl), where ca. 75 species possibly occur. Species checklist for the region was compiled based on bat captures by the authors and from: Lista y distribución de murciélagos de Costa Rica. Rodríguez & Wilson (1999); The mammals of Central America and Southeast Mexico. Reid (2012). Taxonomy according to Simmons (2005). La región del Golfo Dulce está compuesta de bosque estacionalmente húmedo primario y secundario. Esta guía incluye especies representativas de las familias presentes en las tierras bajas de la región (< de 400 m.s.n.m), donde se puede encontrar c. 75 especies. La lista de especies fue preparada con base en capturas de los autores y desde: Lista y distribución de murciélagos de Costa Rica. Rodríguez -

Postweaning Maternal Food Provisioning in a Bat with a Complex Hunting Strategy

Animal Behaviour 85 (2013) 1435e1441 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Animal Behaviour journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/anbehav Postweaning maternal food provisioning in a bat with a complex hunting strategy Inga Geipel a,*, Elisabeth K. V. Kalko a,b, Katja Wallmeyer c, Mirjam Knörnschild a a Institute of Experimental Ecology, Faculty of Natural Sciences, University of Ulm, Ulm, Germany b Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Balboa, Panama c Animal Physiological Ecology, Institute for Evolution and Ecology, University of Tuebingen, Tuebingen, Germany article info Adult animals of many taxa exhibit extended parental care by transferring food to inexperienced offspring, fi Article history: thus allocating nutritional and sometimes even informational bene ts such as the acquisition of adult Received 7 December 2012 dietary preferences and foraging skills. In bats, postweaning food provisioning is severely understudied, Initial acceptance 8 January 2013 despite the taxon’s diverse and complex foraging strategies. The Neotropical common big-eared bat, Final acceptance 18 March 2013 Micronycteris microtis, preys on relatively large insects gleaned from vegetation, finding its silent and Available online 2 May 2013 motionless prey by echolocation. The demands of this cognitively challenging hunting strategy make MS. number: 12-00924R M. microtis a likely candidate for maternal postweaning food provisioning. We studied five free-living mother epup pairs in their night roost using infrared video recordings. Each mother exclusively fed her own pup and Keywords: motherepup recognition was mutual. Provisioned pups were volant and had started their own hunting common big-eared bat attempts. Weaned pups were provisioned for 5 subsequent months with a variety of insects, reflecting the extended parental care adult diet. -

Bat Rabies and Other Lyssavirus Infections

Prepared by the USGS National Wildlife Health Center Bat Rabies and Other Lyssavirus Infections Circular 1329 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Front cover photo (D.G. Constantine) A Townsend’s big-eared bat. Bat Rabies and Other Lyssavirus Infections By Denny G. Constantine Edited by David S. Blehert Circular 1329 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2009 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Constantine, D.G., 2009, Bat rabies and other lyssavirus infections: Reston, Va., U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1329, 68 p. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Constantine, Denny G., 1925– Bat rabies and other lyssavirus infections / by Denny G. Constantine. p. cm. - - (Geological circular ; 1329) ISBN 978–1–4113–2259–2 1. -

Chapter 3. Capture and Marking

CHAPTER 3. CAPTURE AND MARKING A. Overview Scientific studies of birds often require that birds be captured to gather morphometric data and to collect samples for pathological, genetic, and biogeochemical analysis. These data and samples can be used to understand evolutionary relationships, genetics, population structure and dynamics, comparative anatomy and physiology, adaptation, behavior, parasites and diseases, geographic distributions, migration, and the general ecology of wild populations of birds. This knowledge informs us about avian biology and natural history and is necessary to effect science-based conservation and management policies for game and non-game species, endangered species, economically important species, and bird habitat conservation (White and Garrott 1990). Capture is generally necessary to mark birds, which allows scientists to investigate demography, migration/movement patterns, or identify specific individuals after release (Day et al. 1980). Many techniques have been developed to capture and mark birds (Nietfeld et al. 1994; Bub 1995). The assumption that marking does not affect the birds is critical because it is the basis for generalizing the data to unmarked birds (Murray and Fuller 2000). The purpose of this section is not to describe capture and marking techniques, but instead to discuss the effects that different capture and marking techniques have on a bird’s short- and long-term physiological well-being and survival. The more commonly used methods are covered and described briefly, but the focus is on the potential impacts of the method. Thus, even if a particular method is not covered, the researcher is alerted to concerns that may arise and questions to be considered in refining methods so as to reduce impacts. -

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats A agnella, Kerivoula 901 Anchieta’s Bat 814 aquilus, Glischropus 763 Aba Leaf-nosed Bat 247 aladdin, Pipistrellus pipistrellus 771 Anchieta’s Broad-faced Fruit Bat 94 aquilus, Platyrrhinus 567 Aba Roundleaf Bat 247 alascensis, Myotis lucifugus 927 Anchieta’s Pipistrelle 814 Arabian Barbastelle 861 abae, Hipposideros 247 alaschanicus, Hypsugo 810 anchietae, Plerotes 94 Arabian Horseshoe Bat 296 abae, Rhinolophus fumigatus 290 Alashanian Pipistrelle 810 ancricola, Myotis 957 Arabian Mouse-tailed Bat 164, 170, 176 abbotti, Myotis hasseltii 970 alba, Ectophylla 466, 480, 569 Andaman Horseshoe Bat 314 Arabian Pipistrelle 810 abditum, Megaderma spasma 191 albatus, Myopterus daubentonii 663 Andaman Intermediate Horseshoe Arabian Trident Bat 229 Abo Bat 725, 832 Alberico’s Broad-nosed Bat 565 Bat 321 Arabian Trident Leaf-nosed Bat 229 Abo Butterfly Bat 725, 832 albericoi, Platyrrhinus 565 andamanensis, Rhinolophus 321 arabica, Asellia 229 abramus, Pipistrellus 777 albescens, Myotis 940 Andean Fruit Bat 547 arabicus, Hypsugo 810 abrasus, Cynomops 604, 640 albicollis, Megaerops 64 Andersen’s Bare-backed Fruit Bat 109 arabicus, Rousettus aegyptiacus 87 Abruzzi’s Wrinkle-lipped Bat 645 albipinnis, Taphozous longimanus 353 Andersen’s Flying Fox 158 arabium, Rhinopoma cystops 176 Abyssinian Horseshoe Bat 290 albiventer, Nyctimene 36, 118 Andersen’s Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arafura Large-footed Bat 969 Acerodon albiventris, Noctilio 405, 411 Andersen’s Leaf-nosed Bat 254 Arata Yellow-shouldered Bat 543 Sulawesi 134 albofuscus, Scotoecus 762 Andersen’s Little Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arata-Thomas Yellow-shouldered Talaud 134 alboguttata, Glauconycteris 833 Andersen’s Naked-backed Fruit Bat 109 Bat 543 Acerodon 134 albus, Diclidurus 339, 367 Andersen’s Roundleaf Bat 254 aratathomasi, Sturnira 543 Acerodon mackloti (see A. -

NFBB Vol. 32 1957

Howard L. Cogswell, Mills College, Oakland, Calif. Russel H. Pray, 662 Santa Rosa Ave., Berkeley, Calif. William K. Kirsher, .571 Fulton Ave., Sacramento, Calif. Lillian Henningson, 124 Cambridge Way, Piedmont, Calif. Address contributions for the N~VS to William K. Kirsher, F~itor-- .571 Fulton Avenue Sacramento 2.5, California PAGE EIGHTEEN THOUSAND AND FOUR CLIFF SWALLOWS by William K. Kirsher. 1 MIST NETS LEGALIZED IN CALIFORNIA. • . 4 MIST NET SUPPLIERS . • . • . • . 6 GULL BANDING IN THE KI~~TH by Carl Richardson • 7 NEVlS FROM TIIEBANDERS. 9 CHAPTER NOTES. • • • . • . • . • 10 EIGHTEEN THOUSAND AND FOUR CLIFF SWALLOWS b:{William K. Kirsher In the flat agricultural lands around Sacramento, California where in prlml- tive times Cliff swallows (petrochelidon p;trrhonota) must have been hard put to find nesting sites, today there are man-made structures that admirably fill the bird's needs for sheltered, elevated purchases for their mud nests. The species now populates the valley abundantly. Colonies are often found in culverts and under small bridges, some no higher than a man's head. In these, by working at night when all the birds are at the nest, practically the whole colony can be trapped by simultaneously closing both openings of the structure with large fish nets. Most of the m,allows flush at the first disturbance, fluttering to the nets where they are easily captured by hand. There are always a few reluctant ones that have to be flushed by shining a bright light (which the bander wears on his forehead) into the nest as he claps his hands and makes hissing sounds and other noises. -

D41586-020-02341-1.Pdf (Nature.Com)

The world this week News in focus PATRICK LANDMANN/SPL PATRICK Controlling deforestation (shown here, in a tropical rainforest in the Congo Basin) could decrease the risk of future pandemics, experts say. WHY DEFORESTATION AND EXTINCTIONS MAKE PANDEMICS MORE LIKELY Researchers are redoubling efforts to understand links between biodiversity and emerging diseases — and to use that information to predict and stop future outbreaks. By Jeff Tollefson growing body of evidence that connects COVID-19 pandemic, efforts to map risks in trends in human development and biodiver- communities around the globe and to project s humans diminish biodiversity by sity loss to disease outbreaks — but stops short where diseases are most likely to emerge are cutting down forests and building of projecting where new disease outbreaks taking centre stage. more infrastructure, they’re increas- might occur. Last week, the Intergovernmental ing the risk of pandemics of diseases “We’ve been warning about this for decades,” Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and such as COVID-19. Many ecologists says Kate Jones, an ecological modeller at Ecosystem Services (IPBES) hosted an online Ahave long suspected this, but a study now University College London and an author of workshop on the nexus between biodiversity helps to reveal why. When some species are the study, published on 5 August in Nature1. loss and emerging diseases. The organization’s going extinct, those that tend to survive and “Nobody paid any attention.” goal now is to produce an expert assessment thrive — rats and bats, for instance — are more Jones is one of a cadre of researchers that has of the science underlying that connection likely to host potentially dangerous pathogens long been delving into relationships between ahead of a United Nations summit that’s that can make the jump to humans. -

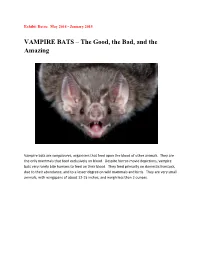

VAMPIRE BATS – the Good, the Bad, and the Amazing

Exhibit Dates: May 2014 - January 2015 VAMPIRE BATS – The Good, the Bad, and the Amazing Vampire bats are sanguivores, organisms that feed upon the blood of other animals. They are the only mammals that feed exclusively on blood. Despite horror-movie depictions, vampire bats very rarely bite humans to feed on their blood. They feed primarily on domestic livestock, due to their abundance, and to a lesser degree on wild mammals and birds. They are very small animals, with wingspans of about 12-15 inches, and weigh less than 2 ounces. SPECIES AND DISTRIBUTIONS Three species of vampire bats are recognized. Vampire bats occur in warm climates in both arid and humid regions of Mexico, Central America, and South America. Distribution of the three species of vampire bats. Common Vampire Bat (Desmodus rotundus) This species is the most abundant and most well-known of the vampire bats. Desmodus feeds mainly on mammals, particularly livestock. They occur from northern Mexico southward through Central America and much of South America, to Uruguay, northern Argentina, and central Chile, and on the island of Trinidad in the West Indies. Common vampire bat, Desmodus rotundus. White-winged Vampire Bat (Diaemus youngi) This species feeds mainly on the blood of birds. They occur from Mexico to southern Argentina and are present on the islands of Trinidad and Isla Margarita. White-winged vampire bat, Diaemus youngi. Hairy-legged Vampire Bat (Diphylla ecaudata) This species also feeds mainly on the blood of birds. They occur from Mexico to Venezuela, Peru, Bolivia, and Brazil. One specimen was collected in 1967 from an abandoned railroad tunnel in Val Verde County, Texas.