Organised Crime Around the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organized Crime and Terrorist Activity in Mexico, 1999-2002

ORGANIZED CRIME AND TERRORIST ACTIVITY IN MEXICO, 1999-2002 A Report Prepared by the Federal Research Division, Library of Congress under an Interagency Agreement with the United States Government February 2003 Researcher: Ramón J. Miró Project Manager: Glenn E. Curtis Federal Research Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 20540−4840 Tel: 202−707−3900 Fax: 202−707−3920 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://loc.gov/rr/frd/ Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Criminal and Terrorist Activity in Mexico PREFACE This study is based on open source research into the scope of organized crime and terrorist activity in the Republic of Mexico during the period 1999 to 2002, and the extent of cooperation and possible overlap between criminal and terrorist activity in that country. The analyst examined those organized crime syndicates that direct their criminal activities at the United States, namely Mexican narcotics trafficking and human smuggling networks, as well as a range of smaller organizations that specialize in trans-border crime. The presence in Mexico of transnational criminal organizations, such as Russian and Asian organized crime, was also examined. In order to assess the extent of terrorist activity in Mexico, several of the country’s domestic guerrilla groups, as well as foreign terrorist organizations believed to have a presence in Mexico, are described. The report extensively cites from Spanish-language print media sources that contain coverage of criminal and terrorist organizations and their activities in Mexico. -

31 August 2020 at 10.01 Am

INDEPENDENT LIQUOR AND GAMING AUTHORITY OF NSW INQUIRY UNDER SECTION 143 OF THE CASINO CONTROL ACT 1992 (NSW) THE HONOURABLE PA BERGIN SC COMMISSIONER PUBLIC HEARING SYDNEY MONDAY, 31 AUGUST 2020 AT 10.01 AM Continued from 24.8.20 DAY 19 Any person who publishes any part of this transcript in any way and to any person contrary to an Inquiry direction against publication commits an offence against section 143B of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW) .NSW CASINO INQUIRY 31.8.20 P-1612 MS N. SHARP SC appears as counsel assisting the Inquiry MR N. YOUNG QC appears with MS R. ORR QC and MR H.C. WHITWELL for Crown Resorts Limited & Crown Sydney Gaming Proprietary Limited MS R. HIGGINS SC and MR D. BARNETT appears for CPH Crown Holdings 5 Pty Ltd MS N. CASE appears for Melco Resorts & Entertainment Limited COMMISSIONER: Yes, thank you. Yes, Ms Sharp. 10 MS SHARP: Good morning, Commissioner. We have Mr Vickers beaming in from Hong Kong. COMMISSIONER: Yes, thank you. 15 MS SHARP: Just before we do that, I see a number of counsel are also present. COMMISSIONER: Excellent. I think it’s the same representation. Mr Young, Mr Barnett, Ms Case. Is that correct? 20 MR N. YOUNG QC: Commissioner, I appear with MS ORR and MR WHITWELL today. COMMISSIONER: Thank you. 25 MR YOUNG: There are some preliminary matters we wish to raise before we go to any evidence. COMMISSIONER: Yes, I will come back to you shortly. Yes, Ms Sharp. 30 MS SHARP: I was going to tender the new lists. -

Mexican Raza!

Valuable Coupons Inside! Gratis! www.laprensatoledo.com Ohio & Michigan’s Oldest & Largest Latino Weekly «Tinta con sabor» • Proudly Serving Our Readers since 1989 • Check out our Classifieds! ¡Checa los Anuncios Clasificados! La Prensa’s Quinceañera Year August/agosto 18, 2004 Spanglish Weekly/Semanal 20 Páginas Vol. 35, No. 23 Taquería El Nacimiento Olympics: Puerto Rico defeats EEUU, page 15 Mexican DENTRO: EEUU permitirá más Restaurant largas para visitantes mexicanos........................3 Welcome! Horoscopes.....................5 Hours: Carry-Out Mon-Thur: 9AM-12AM Phone: 313.554.1790 Carla’s Krazy Fri & Sat: 9AM-3AM 7400 W. Vernor Hwy. Korner............................6 Sun: 9AM-12AM Detroit MI 48209 Grito de “HoOoOtT DoOoOgGs”..................6 • Jugos/Tepache • Carne a la Parrilla • Tacos • Burritos Deportes..........................7 • Aguas • Pollo Dorado • Mojarra Frita • Licuados Lottery Results.............7 • Tortas • Quesadillas Olympian Devin • Tostadas • Pozole Vargas.............................8 • Caldos • Carne de Puerco en salsa verde •Mariscos • Breakfast Super Burro Calendar of Events............................12 ¡Bienvenidos I-75 August 14: Gustavo (Gus) Hoyas de Nationwide, Ohio Insurance Director Ann Classifieds.............15-18 Raza! Womer Benjamin, and Angel Guzman, CEO of the Hispanic Business Association. Livernois Athens 2004..........14-15 W. Vernor Springwells Nationwide celebra apertura de nueva oficina en Cleveland Salon Unisex Breves: por Teodosio Feliciano, reportero y fotógrafo de La Prensa Latinoamérica es escenario Janet García se supone que Gibson (Bill) inmediatamente Janet no solo coordinó del 75% de los secuestros solamente iba organizar la vio que esta energética joven la gran apertura pero es en el mundo apertura de la oficina Cleve- latina tenia el talento, la agente asociada y ancla para Por NIKO PRICE land Community Insurance personalidad y actitud para la oficina para Nationwide de la agencia Gibson Insur- sobresalir en el negocio de Insurance y Financial Ser MEXICO (AP): Con una ance. -

Israel Convicts Eichmann of Crimes Against Jews

• I \ \ I • • ■ Stores Open 9.o*Ciock for Christmas mg Avitniffe Daily Net Prees Run For the Week Ended The Weather / December t, 1961 Forecast of D. S. Weather Bnreee Moderatdy cold tonight snow 13,518 or rain beatamlnc tomsrd day Member of the Audit break. Low 26 to 82. Tiieeday rain Burenu of OlreuUtlon Or snow changtor to rain. Hlah 85 to 40. ( ■ Manchester~^A City of Village Charm VOL. LXXXI, NO. 60 (EIGHTEEN PAGES) MANCHESI'ER, CONN., MONDAY, DECEMBER 11, 1961 (Classified AdvertlslnK on Page 16) PRICE FIVE CENTS Fire Lab Will Test State News How, Why Hospital R oundup Israel Convicts Eichmann Violent Death Fire Spread Rapidly Takes Five in Hartford, Dec. 11 (A*)— 6ame spread of the State Weekend m aterial. Of Crimes Against Jews Deputy State Fire Marshal "If It develops that this flame By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS Carroll E. Shaw will fly to spread is too high for reasonable Fire and highway accident.^ Chicago Wednesday to super safety, then we would ask tjie hos vise tests designed to deter pital to take immediate action to took five live.s in Connecticut mine how and why the Hart remove all materls’s of this kind over the weekend. 10 Changes still In use. We would also order Two persons. Including a 2-ycar- ford Hospital fire spread as the removal of this t>pe of material old boy. were killed in Area and Sentencing of Nazi rapidly as it did. from all other Connecticut hospi three tiled as a result of trafBc ac He will take with him Sgt. -

The Changing Face of Colombian Organized Crime

PERSPECTIVAS 9/2014 The Changing Face of Colombian Organized Crime Jeremy McDermott ■ Colombian organized crime, that once ran, unchallenged, the world’s co- caine trade, today appears to be little more than a supplier to the Mexican cartels. Yet in the last ten years Colombian organized crime has undergone a profound metamorphosis. There are profound differences between the Medellin and Cali cartels and today’s BACRIM. ■ The diminishing returns in moving cocaine to the US and the Mexican domi- nation of this market have led to a rapid adaptation by Colombian groups that have diversified their criminal portfolios to make up the shortfall in cocaine earnings, and are exploiting new markets and diversifying routes to non-US destinations. The development of domestic consumption of co- caine and its derivatives in some Latin American countries has prompted Colombian organized crime to establish permanent presence and structures abroad. ■ This changes in the dynamics of organized crime in Colombia also changed the structure of the groups involved in it. Today the fundamental unit of the criminal networks that form the BACRIM is the “oficina de cobro”, usually a financially self-sufficient node, part of a network that functions like a franchise. In this new scenario, cooperation and negotiation are preferred to violence, which is bad for business. ■ Colombian organized crime has proven itself not only resilient but extremely quick to adapt to changing conditions. The likelihood is that Colombian organized crime will continue the diversification -

Constructing Andean Utopia in Evo Morales's Bolivia

UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title Comparative indigeneities in contemporary Latin America: an analysis of ethnopolitics in Mexico and Bolivia Author(s) Warfield, Cian Publication date 2020 Original citation Warfield, C. 2020. Comparative indigeneities in contemporary Latin America: an analysis of ethnopolitics in Mexico and Bolivia. PhD Thesis, University College Cork. Type of publication Doctoral thesis Rights © 2020, Cian Warfield. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/10551 from Downloaded on 2021-10-09T12:31:58Z Ollscoil na hÉireann, Corcaigh National University of Ireland, Cork Comparative Indigeneities in Contemporary Latin America: Analysis of Ethnopolitics in Mexico and Bolivia Thesis presented by Cian Warfield, BA, M.Res for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University College Cork Department of Spanish, Portuguese and Latin American Studies Head of Department: Professor Nuala Finnegan Supervisor: Professor Nuala Finnegan 2020 Contents Acknowledgements …………………………………………………………………………………………………03 Abstract………………………….……………………………………………….………………………………………….06 Introduction…………………………..……………………………………………………………..…………………..08 Chapter One Tierra y Libertad: The Zapatista Movement and the Struggle for Ethnoterritoriality in Mexico ……………………………………………………………….………………………………..……………………..54 Chapter Two The Struggle for Rural and Urban Ethnoterritoriality in Evo Morales’s Bolivia: The 2011 TIPNIS Controversy -

Business Risk of Crime in China

Business and the Ris k of Crime in China Business and the Ris k of Crime in China Roderic Broadhurst John Bacon-Shone Brigitte Bouhours Thierry Bouhours assisted by Lee Kingwa ASIAN STUDIES SERIES MONOGRAPH 3 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/ National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Business and the risk of crime in China : the 2005-2006 China international crime against business survey / Roderic Broadhurst ... [et al.]. ISBN: 9781921862533 (pbk.) 9781921862540 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Crime--China--21st century--Costs. Commercial crimes--China--21st century--Costs. Other Authors/Contributors: Broadhurst, Roderic G. Dewey Number: 345.510268 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Cover image: The gods of wealth enter the home from everywhere, wealth, treasures and peace beckon; designer unknown, 1993; (Landsberger Collection) International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam. Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2011 ANU E Press Contents Foreword . vii Lu Jianping Preface . ix Acronyms . xv Introduction . 1 1 . Background . 25 2 . Crime and its Control in China . 43 3 . ICBS Instrument, Methodology and Sample . 79 4 . Common Crimes against Business . 95 5 . Fraud, Bribery, Extortion and Other Crimes against Business . -

CONTEMPORARY PROXIMITY FICTION. GUEST EDITED by NADIA ALONSO VOLUME IV, No 01 · SPRING 2018

CONTEMPORARY PROXIMITY FICTION. GUEST EDITED BY NADIA ALONSO VOLUME IV, No 01 · SPRING 2018 PUBLISHED WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF EDITORS ABIS – AlmaDL, Università di Bologna Veronica Innocenti, Héctor J. Pérez and Guglielmo Pescatore. E-MAIL ADDRESS ASSOCIATE EDITOR [email protected] Elliott Logan HOMEPAGE GUEST EDITORS series.unibo.it Nadia Alonso ISSN SECRETARIES 2421-454X Luca Barra, Paolo Noto. DOI EDITORIAL BOARD https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.2421-454X/v4-n1-2018 Marta Boni, Université de Montréal (Canada), Concepción Cascajosa, Universidad Carlos III (Spain), Fernando Canet Centellas, Universitat Politècnica de València (Spain), Alexander Dhoest, Universiteit Antwerpen (Belgium), Julie Gueguen, Paris 3 (France), Lothar Mikos, Hochschule für Film und Fernsehen “Konrad Wolf” in Potsdam- Babelsberg (Germany), Jason Mittell, Middlebury College (USA), Roberta Pearson, University of Nottingham (UK), Xavier Pérez Torio, Universitat Pompeu Fabra (Spain), Veneza Ronsini, Universidade SERIES has two main purposes: first, to respond to the surge Federal de Santa María (Brasil), Massimo Scaglioni, Università Cattolica di Milano (Italy), Murray Smith, University of Kent (UK). of scholarly interest in TV series in the past few years, and compensate for the lack of international journals special- SCIENTIFIC COMMITEE izing in TV seriality; and second, to focus on TV seriality Gunhild Agger, Aalborg Universitet (Denmark), Sarah Cardwell, through the involvement of scholars and readers from both University of Kent (UK), Sonja de Leeuw, Universiteit Utrecht (Netherlands), Sergio Dias Branco, Universidade de Coimbra the English-speaking world and the Mediterranean and Latin (Portugal), Elizabeth Evans, University of Nottingham (UK), Aldo American regions. This is the reason why the journal’s official Grasso, Università Cattolica di Milano (Italy), Sarah Hatchuel, languages are Italian, Spanish and English. -

TRIADS Peter Yam Tat-Wing *

116TH INTERNATIONAL TRAINING COURSE VISITING EXPERTS’ PAPERS TRIADS Peter Yam Tat-wing * I. INTRODUCTION This paper will draw heavily on the experience gained by law enforcement Triad societies are criminal bodies in the HKSAR in tackling the triad organisations and are unlawful under the problem. Emphasis will be placed on anti- Laws of Hong Kong. Triads have become a triad law and Police enforcement tactics. matter of concern not only in Hong Kong, Background knowledge on the structure, but also in other places where there is a beliefs and rituals practised by the triads sizable Chinese community. Triads are is important in order to gain an often described as organized secret understanding of the spread of triads and societies or Chinese Mafia, but these are how triads promote illegal activities by simplistic and inaccurate descriptions. resorting to triad myth. With this in mind Nowadays, triads can more accurately be the paper will examine the following issues: described as criminal gangs who resort to triad myth to promote illegal activities. • History and Development of Triads • Triad Hierarchy and Structure For more than one hundred years triad • Characteristics of Triads activities have been noted in the official law • Differences between Triads, Mafia and police reports of Hong Kong. We have and Yakuza a long history of special Ordinances and • Common Crimes Committed by related legislation to deal with the problem. Triads The first anti-triad legislation was enacted • Current Triad Situation in Hong in 1845. The Hong Kong Special Kong Administrative Region (HKSAR) has, by • Anti-triad Laws in Hong Kong far, the longest history, amongst other • Police Enforcement Strategy jurisdictions, in tackling the problem of • International Cooperation triads and is the only jurisdiction in the world where specific anti-triad law exists. -

Gender-Based Violence and Environment Linkages the Violence of Inequality Itzá Castañeda Camey, Laura Sabater, Cate Owren and A

Gender-based violence and environment linkages The violence of inequality Itzá Castañeda Camey, Laura Sabater, Cate Owren and A. Emmett Boyer Jamie Wen, editor INTERNATIONAL UNION FOR CONSERVATION OF NATURE About IUCN IUCN is a membership Union uniquely composed of both government and civil society organisations. It provides public, private and non-governmental organisations with the knowledge and tools that enable human progress, economic development and nature conservation to take place together. Created in 1948, IUCN is now the world’s largest and most diverse environmental network, harnessing the knowledge, resources and reach of more than 1,300 Member organisations and some 15,000 experts. It is a leading provider of conservation data, assessments and analysis. Its broad membership enables IUCN to fill the role of incubator and trusted repository of best practices, tools and international standards. IUCN provides a neutral space in which diverse stakeholders including governments, NGOs, scientists, businesses, local communities, Indigenous Peoples organisations and others can work together to forge and implement solutions to environmental challenges and achieve sustainable development. Working with many partners and supporters, IUCN implements a large and diverse portfolio of conservation projects worldwide. Combining the latest science with the traditional knowledge of local communities, these projects work to reverse habitat loss, restore ecosystems and improve people’s well-being. www.iucn.org https://twitter.com/IUCN/ Gender-based violence and environment linkages The violence of inequality Itzá Castañeda Camey, Laura Sabater, Cate Owren and A. Emmett Boyer Jamie Wen, editor The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Transnational Threats Update

TRANSNATIONAL THREATS UPDATE Volume 3 • Number 8 • June 2005 “Defending our Nation against its enemies is the first and fundamental commitment of the Federal Government. Today, that task has changed dramatically. Enemies in the past needed great armies and great industrial capabilities to endanger America. Now, shadowy networks of individuals can bring great chaos and suffering to our shores for less than it costs to purchase a single tank. Terrorists are organized to penetrate open societies and to turn the power of modern technologies against us.” President George W. Bush, 2002 National Security Strategy was killed while placing a roadside bomb along the CONTENTS Damascus-Zabadani road in January. No official Terrorism.…………………….…..…………1 confirmation of the story was released, but Syria’s Money Laundering…….……………….....3 newspapers, which provided details of the raid and the Drug Trafficking…..……………………….3 thwarted terror attack, are government-controlled. Organized Crime…..….…..……………….4 Antiterror Measures…..……………..…...6 The name of the group Jund al-Sham Organization for Jihad and Tawhid surfaced for the first time following this incident. According to the London-based Arabic Terrorism newspaper Al-Hayat, the group had an “ideological, political, and military project against the political Terrorist Cell Broken Up in Syria systems and positive laws in the three countries of Bilad al-Sham—Syria, Jordan and Lebanon—and On June 10, Syrian law enforcement dismantled a against Iraq, which is occupied by the Crusaders.” terrorist cell that was part of a radical group called Death threats to Islamic deputy Muhammad Habash Jund al-Sham Organization for Jihad and Tawhid. The and accusations of agnosticism over the past few leader of the cell, Abu-Umar, and his assistant, Abu- months may be evidence of pockets of emerging Ahmad, were killed during a raid of a house on the intolerance and fanaticism in this authoritarian country. -

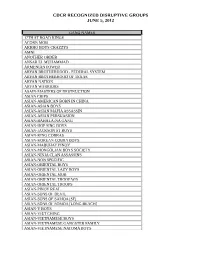

Cdcr Recognized Disruptive Groups June 5, 2012

CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 GANG NAMES 17TH ST ROAD KINGS ACORN MOB AKRHO BOYS CRAZZYS AMNI ANOTHER ORDER ANSAR EL MUHAMMAD ARMENIAN POWER ARYAN BROTHERHOOD - FEDERAL SYSTEM ARYAN BROTHERHOOD OF TEXAS ARYAN NATION ARYAN WARRIORS ASAIN-MASTERS OF DESTRUCTION ASIAN CRIPS ASIAN-AMERICAN BORN IN CHINA ASIAN-ASIAN BOYS ASIAN-ASIAN MAFIA ASSASSIN ASIAN-ASIAN PERSUASION ASIAN-BAHALA-NA GANG ASIAN-HOP SING BOYS ASIAN-JACKSON ST BOYS ASIAN-KING COBRAS ASIAN-KOREAN COBRA BOYS ASIAN-MABUHAY PINOY ASIAN-MONGOLIAN BOYS SOCIETY ASIAN-NINJA CLAN ASSASSINS ASIAN-NON SPECIFIC ASIAN-ORIENTAL BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL LAZY BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL MOB ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOP W/S ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOPS ASIAN-PINOY REAL ASIAN-SONS OF DEVIL ASIAN-SONS OF SAMOA [SF] ASIAN-SONS OF SOMOA [LONG BEACH] ASIAN-V BOYS ASIAN-VIET CHING ASIAN-VIETNAMESE BOYS ASIAN-VIETNAMESE GANGSTER FAMILY ASIAN-VIETNAMESE NATOMA BOYS CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 ASIAN-WAH CHING ASIAN-WO HOP TO ATWOOD BABY BLUE WRECKING CREW BARBARIAN BROTHERHOOD BARHOPPERS M.C.C. BELL GARDENS WHITE BOYS BLACK DIAMONDS BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLE BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLES NATION BLACK GANGSTERS BLACK INLAND EMPIRE MOB BLACK MENACE MAFIA BLACK P STONE RANGER BLACK PANTHERS BLACK-NON SPECIFIC BLOOD-21 MAIN BLOOD-916 BLOOD-ATHENS PARK BOYS BLOOD-B DOWN BOYS BLOOD-BISHOP 9/2 BLOOD-BISHOPS BLOOD-BLACK P-STONE BLOOD-BLOOD STONE VILLAIN BLOOD-BOULEVARD BOYS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER [LOT BOYS] BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-BELHAVEN BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-INCKERSON GARDENS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-NICKERSON