Extreme Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Milla Jovovich

Textes : COMING SOON COMMUNICATION • Design : Fabrication Maison / TROÏKA . SAMUEL HADIDA et METROPOLITAN FILMEXPORT présentent une production CONSTANTIN FILM/ DAVIS FILMS/ IMPACT PICTURES un film de RUSSELL MULCAHY MILLA JOVOVICH ODED FEHR ALI LARTER IAIN GLEN ASHANTI MIKE EPPS Un film produit par Bernd Eichinger, Samuel Hadida, Robert Kulzer, Jeremy Bolt et Paul W.S. Anderson SORTIE LE 3 OCTOBRE 2007 Durée : 1h30 Vous pouvez télécharger l'affiche et des photos du film sur : http://presse.metropolitan-films.com www.metrofilms.com www.re3.fr DISTRIBUTION RELATIONS PRESSE METROPOLITAN FILMEXPORT PROGRAMMATION PARTENARIATS KINEMA FILM / François Frey 29, rue Galilée - 75116 Paris Region Paris GRP-Est-Nord ET PROMOTION 15, rue Jouffroy-d’Abbans [email protected] Tél. : 01 56 59 23 25 AGENCE MERCREDI 75017 Paris Tél. : 01 56 59 23 25 Region Marseille-Lyon-Bordeaux Tél. : 01 56 59 66 66 Tél. : 01 43 18 80 00 Fax : 01 53 57 84 02 Tél. : 05 56 44 04 04 Fax : 01 56 59 66 67 Fax : 01 43 18 80 09 Le virus expérimental mis au point par la toute-puissante Umbrella Corporation a détruit l’humanité, transformant la population du monde en zombies avides de chair humaine. Fuyant les villes, Carlos, L.J., Claire, K-Mart, Nurse Betty et quelques survivants ont pris la route dans un convoi armé, espérant retrouver d’autres humains non infectés et gagner l’Alaska, leur dernier espoir d’une terre préservée. Ils sont accompagnés dans l’ombre par Alice, une jeune femme sur laquelle Umbrella a mené autrefois de terribles expériences biogéniques qui, en modifiant son ADN, lui ont apporté des capacités surhumaines. -

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs The thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth. September 2014 Declaration Whilst registered as a candidate for the above degree, I have not been registered for any other research award. The results and conclusions embodied in this thesis are the work of the named candidate and have not been submitted for any other academic award. Word count: 85,810 Abstract Extreme art cinema, has, in recent film scholarship, become an important area of study. Many of the existing practices are motivated by a Franco-centric lens, which ultimately defines transgressive art cinema as a new phenomenon. The thesis argues that a study of extreme art cinema needs to consider filmic production both within and beyond France. It also argues that it requires an historical analysis, and I contest the notion that extreme art cinema is a recent mode of Film production. The study considers extreme art cinema as inhabiting a space between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art forms, noting the slippage between the two often polarised industries. The study has a focus on the paratext, with an analysis of DVD extras including ‘making ofs’ and documentary featurettes, interviews with directors, and cover sleeves. This will be used to examine audience engagement with the artefacts, and the films’ position within the film market. Through a detailed assessment of the visual symbols used throughout the films’ narrative images, the thesis observes the manner in which they engage with the taste structures and pictorial templates of art and exploitation cinema. -

BFI CELEBRATES BRITISH FILM at CANNES British Entry for Cannes 2011 Official Competition We’Ve Got to Talk About Kevin Dir

London May 10 2011: For immediate release BFI CELEBRATES BRITISH FILM AT CANNES British entry for Cannes 2011 Official Competition We’ve Got to Talk About Kevin dir. Lynne Ramsay UK Film Centre supports delegates with packed events programme 320 British films for sale in the market A Clockwork Orange in Cannes Classics The UK film industry comes to Cannes celebrating the selection of Lynne Ramsay’s We Need to Talk About Kevin for the official competition line-up at this year’s festival, Duane Hopkins’s short film, Cigarette at Night, in the Directors’ Fortnight and the restoration of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, restored by Warner Bros; in Cannes Classics. Lynne Ramsay’s We Need To Talk About Kevin starring Tilda Swinton was co-funded by the UK Film Council, whose film funding activities have now transferred to the BFI. Duane Hopkins is a director who was supported by the UK Film Council with his short Love Me and Leave Me Alone and his first feature Better Things. Actor Malcolm McDowell will be present for the screening of A Clockwork Orange. ITV Studios’ restoration of A Night to Remember will be screened in the Cinema on the Beach, complete with deckchairs. British acting talent will be seen in many films across the festival including Carey Mulligan in competition film Drive, and Tom Hiddleston & Michael Sheen in Woody Allen's opening night Midnight in Paris The UK Film Centre offers a unique range of opportunities for film professionals, with events that include Tilda Swinton, Lynne Ramsay and Luc Roeg discussing We Need to Talk About Kevin, The King’s Speech producers Iain Canning and Gareth Unwin discussing the secrets of the film’s success, BBC Film’s Christine Langan In the Spotlight and directors Nicolas Winding Refn and Shekhar Kapur in conversation. -

Black Light Burns Cruel Melody Mp3, Flac, Wma

Black Light Burns Cruel Melody mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Rock Album: Cruel Melody Country: US Released: 2007 Style: Electro, Goth Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1390 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1273 mb WMA version RAR size: 1864 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 555 Other Formats: VQF WMA AU VOX MOD AC3 MIDI Tracklist Hide Credits Mesopotamia 1 4:29 Mixed By – Ross Robinson, Ryan Boesch 2 Animal 4:08 Lie 3 4:21 Bass – Danny LohnerProgrammed By [Additional] – Charlie Clouser Coward 4 4:36 Bass, Guitar – Danny LohnerVocals [Additional] – Sonny Moore Cruel Melody 5 5:00 Vocals [Additional] – Carina Round 6 The Mark 3:13 I Have A Need 7 4:24 Bass – Sam Rivers Guitar – Danny Lohner 8 4 Walls 3:51 9 Stop A Bullet 3:37 10 One Of Yours 4:51 New Hunger 11 Cello – John Krovoza, Matt Cooker*, Richard Dodd Viola – Leah KatzViolin – Daphne Chen, 5:24 Eric Gorfain I Am Where It Takes Me 12 Cello – John Krovoza, Matt Cooker*, Richard Dodd Drums – Wes BorlandViola – Leah 6:09 KatzViolin – Daphne Chen, Eric GorfainVocals [Additional] – Johnette Napolitano Iodine Sky 13 8:30 Mixed By – Wes Borland Credits Drums, Percussion – Josh Freese Engineer – Critter*, Josh Eustis* Engineer [Additional] – Danny Lohner, Wes Borland Lead Vocals, Guitar, Bass, Programmed By, Percussion, Synthesizer, Piano, Electric Piano [Rhodes], Violin, Cello – Wes Borland Mixed By – Tom Lord-Alge (tracks: 2 to 12) Performer [Live Bass] – Sean Fetterman Performer [Live Drums] – Marshall Kilpatric Performer [Live Guitar] – Nick Annis Performer [Live Vocals, Guitar] -

Proceedings 2012

TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction iv Beacon 2012 Sponsors v Conference Program vi Outstanding Papers by Panel 1 SESSION I POLITICAL SCIENCE 2 Alison Conrad “Negative Political Advertising and the American Electorate” Mentor: Prof. Elaine Torda Orange County Community College EDUCATION 10 Michele Granitz “Non-Traditional Women of a Local Community College” Mentor: Dr. Bahar Diken Reading Area Community College INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDIES 18 Brogan Murphy “The Missing Link in the Puzzling Autism Epidemic: The Effect of the Internet on the Social Impact Equation” Mentor: Prof. Shweta Sen Montgomery College HISTORY 31 Megan G. Willmes “The People’s History vs. Company Profit: Mine Wars in West Virginia, the Battle of Blair Mountain, and the Ongoing Fight for Historical Preservation” Mentor: Dr. Joyce Brotton Northern Virginia Community College COMMUNICATIONS I: POPULAR CULTURE 37 Cristiana Lombardo “Parent-Child Relationships in the Wicked Child Sub-Genre of Horror Movies” Mentor: Dr. Mira Sakrajda Westchester Community College ALLIED HEALTH AND NURSING 46 Ana Sicilia “Alpha 1 Anti-Trypsin Deficiency Lung Disease Awareness and Latest Treatments” Mentor: Dr. Amy Ceconi Bergen Community College i TABLE OF CONTENTS (CONTINUED) SESSION II PSYCHOLOGY 50 Stacy Beaty “The Effect of Education and Stress Reduction Programs on Feelings of Control and Positive Lifestyle Changes in Cancer Patients and Survivors” Mentor: Dr. Gina Turner and Dr. Sharon Lee-Bond Northampton Community College THE ARTS 60 Angelica Klein “The Art of Remembering: War Memorials Past and Present” Mentor: Prof. Robert Bunkin Borough of Manhattan Community College NATURAL AND PHYSICAL SCIENCES 76 Fiorella Villar “Characterization of the Tissue Distribution of the Three Splicing Variants of LAMP-2” Mentor: Prof. -

The Killer Inside Me

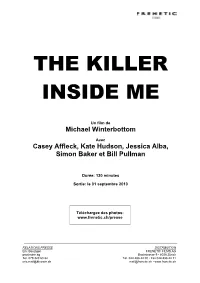

THE KILLER INSIDE ME Un film de Michael Winterbottom Avec Casey Affleck, Kate Hudson, Jessica Alba, Simon Baker et Bill Pullman Durée: 120 minutes Sortie: le 01 septembre 2010 Téléchargez des photos: www.frenetic.ch/presse RELATIONS PRESSE DISTRIBUTION Eric Bouzigon FRENETIC FILMS AG prochaine ag Bachstrasse 9 • 8038 Zürich Tél. 079 320 63 82 Tél. 044 488 44 00 • Fax 044 488 44 11 [email protected] [email protected] • www.frenetic.ch SYNOPSIS Based on the novel by legendary pulp writer Jim Thompson, Michael Winterbottom’s THE KILLER INSIDE ME tells the story of handsome, charming, unassuming small town sheriff’s deputy Lou Ford. Lou has a bunch of problems. Woman problems. Law enforcement problems. An ever-growing pile of murder victims in his west Texas jurisdiction. And the fact he’s a sadist, a psychopath, a killer. Suspicion begins to fall on Lou, and it’s only a matter of time before he runs out of alibis. But in Thompson’s savage, bleak, blacker than noir universe nothing is ever what it seems, and it turns out that the investigators pursuing him might have a secret of their own. CAST Lou Ford.........................................................................................................................................CASEY AFFLECK Joyce Lakeland ..................................................................................................................................JESSICA ALBA Amy Stanton..................................................................................................................................... -

4. Film As Basis for Poster Examination

University of Lapland, Faculty of Art and Design Title of the pro gradu thesis: Translating K-Horror to the West: The Difference in Film Poster Design For South Koreans and an International Audience Author: Meri Aisala Degree program: Graphic Design Type of the work: Pro Gradu master’s thesis Number of pages: 65 Year of publication: 2018 Cover art & layout: Meri Aisala Summary For my pro gradu master’s degree, I conducted research on the topic of South Korean horror film posters. The central question of my research is: “How do the visual features of South Korean horror film posters change when they are reconstructed for an international audience?” I compare examples of original Korean horror movie posters to English language versions constructed for an international audience through a mostly American lens. My study method is semiotics and close reading. Korean horror posters have their own, unique style that emphasizes emotion and interpersonal relationships. International versions of the posters are geared toward an audience from a different visual culture and the poster designs get translated accordingly, but they still maintain aspects of Korean visual style. Keywords: K-Horror, melodrama, genre, subgenre, semiotics, poster I give a permission the pro gradu thesis to be read in the Library. 2 목차Contents Summary 2 1. Introduction 4 1.1 Research problem and goals 4 1.2 The movie poster 6 1.3 The special features of K-Horror 7 1.3.1 Defining the horror genre 7 1.3.2 The subgenres of K-Horror 8 1.3.3 Melodrama 9 2. Study methods and material 12 2.1 Semiotics 12 2.2 Close reading 18 2.3 Differences in visual culture - South Korea and the West 19 3. -

Between Liminality and Transgression: Experimental Voice in Avant-Garde Performance

BETWEEN LIMINALITY AND TRANSGRESSION: EXPERIMENTAL VOICE IN AVANT-GARDE PERFORMANCE _________________________________________________________________ A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theatre and Film Studies in the University of Canterbury by Emma Johnston ______________________ University of Canterbury 2014 ii Abstract This thesis explores the notion of ‘experimental voice’ in avant-garde performance, in the way it transgresses conventional forms of vocal expression as a means of both extending and enhancing the expressive capabilities of the voice, and reframing the social and political contexts in which these voices are heard. I examine these avant-garde voices in relation to three different liminal contexts in which the voice plays a central role: in ritual vocal expressions, such as Greek lament and Māori karanga, where the voice forms a bridge between the living and the dead; in electroacoustic music and film, where the voice is dissociated from its source body and can be heard to resound somewhere between human and machine; and from a psychoanalytic perspective, where the voice may bring to consciousness the repressed fears and desires of the unconscious. The liminal phase of ritual performance is a time of inherent possibility, where the usual social structures are inverted or subverted, but the liminal is ultimately temporary and conservative. Victor Turner suggests the concept of the ‘liminoid’ as a more transgressive alternative to the liminal, allowing for permanent and lasting social change. It may be in the liminoid realm of avant-garde performance that voices can be reimagined inside the frame of performance, as a means of exploring new forms of expression in life. -

Understanding a Serbian Film: the Effects of Censorship and File- Sharing on Critical Reception and Perceptions of Serbian National Identity in the UK Kapka, A

Understanding A Serbian Film: The Effects of Censorship and File- sharing on Critical Reception and Perceptions of Serbian National Identity in the UK Kapka, A. (2014). Understanding A Serbian Film: The Effects of Censorship and File-sharing on Critical Reception and Perceptions of Serbian National Identity in the UK. Frames Cinema Journal, (6). http://framescinemajournal.com/article/understanding-a-serbian-film-the-effects-of-censorship-and-file-sharing- on-critical-reception-and-perceptions-of-serbian-national-identity-in-the-uk/ Published in: Frames Cinema Journal Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2017 University of St Andrews and contributers.This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. -

Metropolis Filmelméleti És Filmtörténeti Folyóirat 20. Évf. 3. Sz. (2016/3.)

900 Ft 2016 03 Filmfesztiválok filmelméleti és filmtörténeti folyóirat 2016 3. szám Filmfesztiválok Fahlenbrach8_Layout 1 2016.05.08. 4:13 Page 26 c[jhefeb_i <_bc[bcb[j_ i \_bcjhjd[j_ \ebo_hWj t a r t a l o m XX. évfolyam 3. szám A szerkesztõbizottság Filmfesztiválok tagjai: Bíró Yvette 6 Fábics Natália: Bevezetõ a Filmfesztiválok összeállításhoz Gelencsér Gábor Hirsch Tibor 8 Thomas Elsaesser: A filmfesztiválok hálózata Király Jenõ A filmmûvészet új európai topográfiája Kovács András Bálint Fábics Natália fordítása A szerkesztôség tagjai: 28 Dorota Ostrowska: A cannes-i filmfesztivál filmtörténeti szerepe Vajdovich Györgyi Fábics Natália fordítása Varga Balázs Vincze Teréz 40 Varga Balázs: Presztízspiacok Filmek, szerzõk és nemzeti filmkultúrák a nemzetközi A szám szerkesztõi: fesztiválok kortárs hálózatában Fábics Natália Varga Balázs 52 Fábics Natália: Vér és erõszak nélkül a vörös szõnyegen Takashi Miike, az ázsiai mozi rosszfiújának átmeneti Szerkesztõségi munkatárs: domesztikálódása Jordán Helén 60 Orosz Anna Ida: Az animációsfilm-mûvészet védõbástyái Korrektor: Jagicza Éva 67 Filmfesztiválok — Válogatott bibliográfia Szerkesztõség: 1082 Bp., Horváth Mihály tér 16. K r i t i k a Tel.: 06-20-483-2523 (Jordán Helén) 72 Árva Márton: Paul A. Schroeder Rodríguez: Latin American E-mail: [email protected] Cinema — A Comparative History Felelõs szerkesztõ: 75 Szerzõink Vajdovich Györgyi ISSN 1416-8154 Kiadja: Számunk megjelenéséhez segítséget nyújtott Kosztolányi Dezsõ Kávéház a Nemzeti Kulturális Alap. Kulturális Alapítvány Felelõs kiadó: Varga Balázs Terjesztõ: Holczer Miklós [email protected] 36-30-932-8899 Arculatterv: Szász Regina és Szabó Hevér András Tördelõszerkesztõ: Zrinyifalvi Gábor Borítóterv és KÖVETKEZÕ SZÁMUNK TÉMÁJA: nyomdai elõkészítés: Atelier Kft. FÉRFI ÉS NÕI SZEREPEK A MAGYAR FILMBEN Nyomja: X-Site.hu Kft. -

9 SONGS-B+W-TOR

9 SONGS AFILMBYMICHAEL WINTERBOTTOM One summer, two people, eight bands, 9 Songs. Featuring exclusive live footage of Black Rebel Motorcycle Club The Von Bondies Elbow Primal Scream The Dandy Warhols Super Furry Animals Franz Ferdinand Michael Nyman “9 Songs” takes place in London in the autumn of 2003. Lisa, an American student in London for a year, meets Matt at a Black Rebel Motorcycle Club concert in Brixton. They fall in love. Explicit and intimate, 9 SONGS follows the course of their intense, passionate, highly sexual affair, as they make love, talk, go to concerts. And then part forever, when Lisa leaves to return to America. CAST Margo STILLEY AS LISA Kieran O’BRIEN AS MATT CREW DIRECTOR Michael WINTERBOTTOM DP Marcel ZYSKIND SOUND Stuart WILSON EDITORS Mat WHITECROSS / Michael WINTERBOTTOM SOUND EDITOR Joakim SUNDSTROM PRODUCERS Andrew EATON / Michael WINTERBOTTOM EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Andrew EATON ASSOCIATE PRODUCER Melissa PARMENTER PRODUCTION REVOLUTION FILMS ABOUT THE PRODUCTION IDEAS AND INSPIRATION Michael Winterbottom was initially inspired by acclaimed and controversial French author Michel Houellebecq’s sexually explicit novel “Platform” – “It’s a great book, full of explicit sex, and again I was thinking, how come books can do this but film, which is far better disposed to it, can’t?” The film is told in flashback. Matt, who is fascinated by Antarctica, is visiting the white continent and recalling his love affair with Lisa. In voice-over, he compares being in Antarctica to being ‘two people in a bed - claustrophobia and agoraphobia in the same place’. Images of ice and the never-ending Antarctic landscape are effectively cut in to shots of the crowded concerts. -

Oscars and America 2011

AMERICA AND THE MOVIES WHAT THE ACADEMY AWARD NOMINEES FOR BEST PICTURE TELL US ABOUT OURSELVES I am glad to be here, and honored. I spent some time with Ben this summer in the exotic venues of Oxford and Cambridge, but it was on the bus ride between the two where we got to share our visions and see the similarities between the two. I am excited about what is happening here at Arizona State and look forward to seeing what comes of your efforts. I’m sure you realize the opportunity you have. And it is an opportunity to study, as Karl Barth once put it, the two Bibles. One, and in many ways the most important one is the Holy Scripture, which tells us clearly of the great story of Creation, Fall, Redemption and Consummation, the story by which all stories are measured for their truth, goodness and beauty. But the second, the book of Nature, rounds out that story, and is important, too, in its own way. Nature in its broadest sense includes everything human and finite. Among so much else, it gives us the record of humanity’s attempts to understand the reality in which God has placed us, whether that humanity understands the biblical story or not. And that is why we study the great novels, short stories and films of humankind: to see how humanity understands itself and to compare that understanding to the reality we find proclaimed in the Bible. Without those stories, we would have to go through the experiences of fallen humanity to be able to sympathize with them, and we don’t want to have to do that, unless we have a screw loose somewhere in our brain.