Closing the Circle: the Life of Tzila Zakheim

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

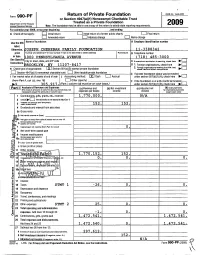

Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1 545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2009 I n t ernal R evenue Service Note . The foundation may be able to use a cony of this return to satisfy state reoortmo reaulrements. For calendar year 2009 , or tax year beginning , and ending G Check all that apply. Initial return 0 Initial return of a former public charity 0 Final return Amended return Address chanae 0 Name chanae Name of foundation A Employer identification number Use the IRS label. Otherwise , JOSEPH CHEHEBAR FAMILY FOUNDATION 11-3388342 print Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number ortype . 1000 PENNSYLVANIA AVENUE ( 718 ) 485-3000 See Specific City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending , check here ^ Instructions. BROOKLYN , NY 11207-8417 D I. Foreign organizations, check here 2. meeting s% test, H Check type of organization: ® Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation =are comp on 0 Section 4947(a )( 1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust 0 Other taxable private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: ® Cash 0 Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part Il, col (c), line 16) 1 Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month terminatio n 10- s 3 0 5 917. (Part 1, column (d) must be on cash basis.) under section 507( b )( 1 ) B), check here Part I Analysis of Revenue and Expenses (a) Revenue and (b ) Net investment (c) Adjusted net ( d) Disbursements (The total of amounts in columns (b). -

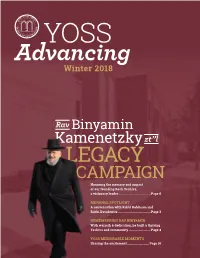

2018-YOSS-Advancing.Pdf

YOSS Advancing Winter 2018 Rav Binyamin Kamenetzky zt”l LEGACY CAMPAIGN Honoring the memory and impact of our founding Rosh Yeshiva, a visionary leader ...................................... Page 6 MENAHEL SPOTLIGHT A conversation with Rabbi Robinson and Rabbi Davidowitz ....................................... Page 3 REMEMBERING RAV BINYAMIN With warmth & dedication, he built a thriving Yeshiva and community .......................... Page 4 YOSS MEMORABLE MOMENTS Sharing the excitement .......................... Page 10 PAGE 2 MESSAGE FROM THE ROSH YESHIVA Sefer Shemos is the story of the emergence of Klal Yisrael from a small tribe of the progeny of Yaakov, to a thriving nation with millions of descendants, who accepted upon themselves the yoke of Torah. It is the story of a nation that went out to a desert and sowed the seeds of the future – a future that thrives to this very day. More than sixty years ago, my grandfather Rav Yaakov Kamenetzky, zt”l, charged my father and mother with the formidable task, “Go to the desert and plant the seeds of Torah.” What started as a fledgling school with six or seven boys, flourished more than a hundred fold. With institutions of tefilah, and higher Torah learning, all the outgrowth of that initial foray into the desert, my father’s impact is not only eternal but ever-expanding. This year’s dinner will mark both the commemoration of those accomplishments and a commitment to the renewal, refurbishment and expansion of the Torah facility he built brick by brick in 1964. Whether you are a student, an alumnus, a parent or community member, my father’s vision touched your life, and I hope that you will join us in honoring his. -

Pirchei Agudas Yisroel of America

בס״ד בס״ד Learning from our Leaders Pirchei Agudas Yisroel of America RavOne Ben time Tzion R’ SegalAbba Shaulneeded was to thego Rosh Yeshiva As they approached their assignedRabbeinu! seats... in Yeshivatto Gateshead Porat withYosef his in son. Yerushalayim. One Someone accidentally afternoon Rav Mutzafi approached him with an padlocked the kitchen door emergency while he was learning. Tatty, but that’s I can’t learn Pesach,with please all the food for tonight’s PIRCHEI Two Adult 2nd cost so much more… hmm that small with this let’s movemeal. to How are we going to class tickets especially for 2 Agudas Yisroel of America boy easily could noise. the first classfeed our 120 hungry Vol: 6 Issue: 18 - י"א אדר א', תשע"ט - please. pass as a child… compartment. Bachurimadults!? February 9, 2019 פרשה: תצוה הפטרה: אתה בן אדם... )יחזקאל מג:י-כז( !!! eyi purho prhhkfi t canjv!!! nrcho tsr nabfbx tsr דף יומי: חולין פ״א מצות עשה: 4 מצות לא תעשה: 3 TorahThoughts was during this time, but מ ֹ ׁשֶ ה There are differing opinions as to where) וְעָשִׂ יתָבִׂגְדֵ יקֹדֶ ׁש לְאַ הֲרֹן ... לְכָבֹודּולְתִׂ פְאָרֶ ת)ׁשְ מֹות כח:ב(. Immediately Rabbi Abba Shaul took all The trainMoshe, attendant Chaim, Don inexplicably and Yosef! did You It is worthwhile to your , אַ הֲ ֹר ן the money he had out of his pocket. allnot can show share up into the collect privilege tickets. of a special And you shall make garments of sanctity for spend extra money for he certainly was not in Egypt.) mitzvah. -

Dear Youth Directors, Youth Chairs, and Youth Leaders, NCYI Is Excited to Continue Our Very Successful Parsha Nation Guides

Dear Youth Directors, Youth chairs, and Youth Leaders, NCYI is excited to continue our very successful Parsha Nation Guides. I hope you’re enjoying and learning from Parsha Nation as much as we are. Putting together Parsha Nation every week is indeed no easy task. It takes a lot of time and effort to ensure that each section, as well as each age group, receives the attention and dedication it deserves. We inspire and mold future leaders. The youth leaders of Young Israel have the distinct honor and privilege to teach and develop the youth of Young Israel. Children today are constantly looking for role models and inspirations to latch on to and learn from. Whether it is actual sit down learning sessions, exciting Parsha trivia games, or even just walking down the hall to the Kiddush room, our youth look to us and watch our every move. It’s not always about the things we say, it’s about the things we do. Our children hear and see everything we do whether we realize it or not. This year we are taking our Youth Services to new heights as we introduce our Leadership Training Shabbaton. This engaging, interactive shabbaton will give youth leader’s hands on experience and practical solutions to effectively guide your youth department. Informal education is key. What the summer shows us as educators is that informal education can deliver better results and help increase our youth’s connection to Hashem. More and more shuls are revamping their youth program to give their children a better connection to shul and to Hashem. -

A Japanese Righteous Gentile: the Sugihara Case1

Chapter 10 A Japanese Righteous Gentile: The Sugihara Case1 In the Avenue of the Righteous Gentiles in the Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial in Jerusalem, Japan is represented by one individual deemed worthy to be included: a man who helped some 6,000 Jews escape from Lithuania in the summer of 1940. His name was Vice Consul Sugihara Chiune (or Sugihara Sempo), who granted transit visas to Japan to some two thousand, six hundred Polish and Lithuanian Jewish families, thus saving them from either probable extermination by the Germans or pro- longed incarceration or Siberian exile by the Soviets. Sugihara would have remained a footnote in history were it not for his efforts, made—as it was later claimed—without the prior approval of, and at times without the knowledge of, his superiors in Tokyo. It is hard to determine what led Sugihara to help Jews, and to what extent he was aware that he would earn a place in Jewish history. Apart from him and Vice Consul Shibata in Shanghai, who alerted the Jewish community in that city to the Meisinger scheme, Japanese civilian or mil- itary officials did not go out of their ways to help Jews, probably because there was no need to. We have already noted that the Japanese government and military had no intention of liquidating the Jews in the territories under their control and consistently rejected German requests that they do so. What led Japan to act the way it did was not the result of any concern for the Jews but rather the result of cool and calculated considerations. -

Maspidim Remember Klal Yisroel's Rebbe, the Novominsker Rebbe

Maspidim Remember Klal Yisroel’s Rebbe, The Novominsker Rebbe April 29, 2020 See the recording of the azkarah below. By: Sandy Eller Harav Elya Brudny, Rosh Yeshiva, Mir Yeshiva and Chaver Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah 22 days later it still seems impossible to believe. As Klal Yisroel continues to mourn the loss of the Novominsker Rebbe, Rabbi Yaakov Perlow ztvk’l, Rosh Agudas Yisroel, chaverim of the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah and family members offered deeply emotional divrei hesped for a leader who was a major guiding force for Torah Jewry in America for decades. With state and local laws still in effect prohibiting public gatherings, maspidim addressed an empty beis medrash at Yeshivas Novominsk, an audience of nearly 60,000 listening through teleconference and livestream as the Novominsker was remembered as Klal Yisroel’s Rebbe. Normally echoing with exuberant sounds oftalmidim learning Torah, the yeshiva’s stark emptiness was yet another painful reminder of the present eis tzarah that has devastated our community. Rabbi Zwiebel waiting at a safe social distance while others were speaking. Throughout the over two hour-long azkarah, Rabbi Perlow was lauded for his unwavering devotion to Klal Yisroel, somehow stretching the hours of each day so that he could immerse himself in his learning and still give his undivided attention to the many organizations and individuals who sought his guidance. In a pre-recorded segment, Rabbi Shmuel Kamenetsky, Rosh HaYeshiva, Talmudical Yeshiva of Philadelphia, described the Rebbe as a “yochid b’yisroel” who cared so deeply for others that their needs became his. No communal issue was deemed too large, too small, or beyond the Novominsker’s realm of expertise, his sage counsel steering Klal Yisroel through turbulent waters when communal institutions such asbris milah, shechitah and yeshiva curriculums were threatened by public officials. -

Cincinnati Torah הרות

בס"ד • A PROJECT OF THE CINCINNATI COMMUNITY KOLLEL • CINCYKOLLEL.ORG תורה מסינסי Cincinnati Torah Vol. VIII, No. XIX Ki Sisa A LESSON FROM THE PARASHA A TIMELY HALACHA RABBI CHAIM HEINEMANN To Life and Beyond GUEST CONTRIBUTOR During the time the Beis Hamikdash SHMUEL BOTNICK (the Holy Temple) existed, our Sages enacted that Torah scholars should “After all, to the well-organized mind, death is but miraculously revitalized. Somehow, the lecture publicly on the laws related the next great adventure.” decree in Heaven that the Jewish people be to each festival thirty days before the Professor Albus Dumbledore* destroyed was issued with such potency that, festival. Therefore, beginning Purim, our on a spiritual dimension, it is as if it actually rabbis should teach the laws of Pesach. I’m no talmid of Dumbledore’s (the Sorting happened. The miracle, therefore, was one in Hat sent me off to Brisk), but you gotta give The source for this is that Moshe stood which we transition from the throes of death right before Pesach and taught the laws him credit when it’s due. Though the quote to a newly acquired, freshly rejuvanated, life. excerpted above is surely cloaked with layers of Pesach Sheini (a makeup offering on of esoteric meaning, for our purposes, I’d If this concept seems abstract, it needn’t the 15th of Iyar for those who were unfit earlier). like to discuss how it goes to the very heart of be. Its message is fully relevant. On Purim Though there are Purim’s essence and the focus of our avodah we were imbued with a new breath of life, those who want to suggest, based on the above, that this obligation is (service) in the days that follow. -

The Baal Teshuva Movement

TAMUZ, 57 40 I JUNE, 19$0 VOLUME XIV, NUMBER 9 $1.25 ' ' The Baal Teshuva Movement Aish Hatorah • Bostoner Rebbe: Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Horowitz• CHABAD • Dvar Yerushalayim • Rabbi Shlomo · Freifeld • Gerrer Rebbe • Rabbi Baruch ·.. Horowitz • Jewish Education Progra . • Kosel Maarovi • Moreshet Avot/ El HaMekorot • NCSY • Neve Yerushalayim •Ohr Somayach . • P'eylim •Rabbi Nota Schiller• Sh' or Yashuv •Rabbi Meir Shuster • Horav Elazar Shach • Rabbi Mendel Weinbach •Rabbi Noach Weinberg ... and much much more. THE JEWISH BSERVER In this issue ... THE BAAL TESHUVA MOVEMENT Prologue . 1 4 Chassidic Insights: Understanding Others Through Ourselves, Rabbi Levi Yitzchok Horowitz. 5 A Time to Reach Out: "Those Days Have Come," Rabbi Baruch Horovitz 8 The First Step: The Teshuva Solicitors, Rabbi Hillel Goldberg 10 Teaching the Men: Studying Gemora-The Means and the Ends of the Teshuva Process, Rabbi Nola Schiller . 13 Teaching the Women: How to Handle a Hungry Heart, Hanoch Teller 16 THE JEWISH OBSERVER (ISSN Watching the Airplanes, Abraham ben Shmuel . 19 0(121-6615) is published monthly, Kiruv in Israel: except Ju!y and August. by the Bringing Them to our Planet, Ezriel Hildesheimer 20 Agudath Israel of America, 5 Beekman Street, New York, N.Y The Homecoming Ordeal: 10038. Second class postage paid Helping the Baal Teshuva in America, at New York, N.Y. Subscription Rabbi Mendel Weinbach . 25 $9.00 per year; two years. $17.50; three years, $25.00; outside of the The American Scene: United States, $10.00 per year. A Famine in the Land, Avrohom Y. HaCohen 27 Single copy, $1.25 Printed in the U.S.A. -

Honoring Others

HONORING OTHERS Sponsored by Jake and Karen Abilevitz in memory of Jake’s Beloved Parents יהושע בן שמעון דב ז"ל and Karen’s brother אליהו בן אבא ז"ל & לאה בת אברהם ז"ל 1) Avos, Chapter 4, Mishna 1 בֶּ ן זוֹמָ א אוֹמֵ ר :Ben Zoma said 1. אֵ יזֶהוּ חָ כָם, הַ לּוֹמֵ ד מִ כָּל אָדָ ם, ,Who is wise? He who learns from every man .1 a. שֶׁ נֶּאֱמַ ר (תהלים קיט) מִ כָּל a. as it is said: “From all who taught me have I gained מְ לַמְּדַ י הִשְׂ כַּלְתִּ י כִּי ﬠֵדְ וֹתֶ י� .(understanding” (Psalms 119:99 שִׂ יחָה לִּ י. ,Who is mighty? He who subdues his [evil] inclination .2 2. אֵ יזֶהוּ גִ בּוֹר, הַכּוֹבֵ שׁ אֶ ת יִצְ רוֹ, a. as it is said: “He that is slow to anger is better than the a. שֶׁ נֶּאֱמַ ר (משלי טז) טוֹב ”mighty; and he that rules his spirit than he that takes a city אֶרֶ � אַפַּיִם מִ גִּ בּוֹר וּמשֵׁ ל .(Proverbs 16:3) בְּ רוּחוֹ מִ �כֵד ﬠִ יר. 3. Who is rich? He who rejoices in his lot, 3. אֵ יזֶהוּ ﬠָשִׁ יר, הַ שָּׂ מֵ חַ בְּ חֶ לְ ק וֹ , a. as it is said: “You shall enjoy the fruit of your labors, you a. שֶׁ נֶּאֱמַ ר (תהלים קכח) יְגִיﬠַ shall be happy and you shall prosper” (Psalms 128:2) “You כַּפֶּ י� כִּ י תֹאכֵל אַשְׁרֶ י� וְטוֹב לָ �. אַשְׁרֶ י�, בָּ עוֹלָ ם הַ זֶּה. shall be happy” in this world, “and you shall prosper” in the וְטוֹב לָ�, לָ עוֹלָ ם הַבָּ א. -

Download Catalog

INTRODUCTION Ohr Somayach-Monsey was originally established in 1979 as a branch of the Jerusalem-based Ohr Somayach Institutions network. Ohr Somayach-Monsey became an independent Yeshiva catering to Ba’alei Teshuvah in 1983. Ohr Somayach-Monsey endeavors to offer its students a conducive environment for personal and intellectual growth through a carefully designed program of Talmudic, ethical and philosophical studies. An exciting and challenging program is geared to developing the students' skills and a full appreciation of an authentic Jewish approach to living. The basic goal of this vigorous academic program is to develop intellectually sophisticated Talmudic scholars who can make a significant contribution to their communities both as teachers and experts in Jewish law; and as knowledgeable lay citizens. Students are selected on a basis of membership in Jewish faith. Ohr Somayach does not discriminate against applicants and students on the basis of race, color, national or ethnic origin provided that they members of the above mentioned denomination. CAMPUS AND FACILITIES Ohr Somayach is located at 244 Route 306 in Monsey, N.Y., a vibrant suburban community 35 miles northwest of New York City. The spacious wooded grounds include a central academic building with a large lecture hall and classrooms and a central administration building. -1- There are dormitory facilities on campus as well as off campus student housing. Three meals a day are served at the school. A full range of student services is provided including tutoring and personal counseling. Monsey is well known as a well developed Jewish community. World famous Talmudical scholars as well as Rabbinical sages in the community are available for personal consultation and discussion. -

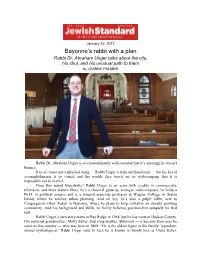

Bayonne's Rabbi with a Plan

January 12, 2017 Bayonne’s rabbi with a plan Rabbi Dr. Abraham Unger talks about the city, his shul, and his unusual path to them by JOANNE PALMER Rabbi Dr. Abraham Unger is so extraordinarily well-rounded that it’s amazing he doesn’t bounce. It is of course not a physical thing — Rabbi Unger is trim and handsome — but his list of accomplishments is so varied, and the worlds they touch are so wide-ranging, that it is impossible not to marvel. Does this sound hyperbolic? Rabbi Unger is an actor with credits in commercials, television, and three feature films; he’s a classical guitarist, arranger, and composer; he holds a Ph.D. in political science and is a tenured associate professor at Wagner College on Staten Island, where he teaches urban planning. And oh yes, he’s also a pulpit rabbi, new to Congregation Ohav Zedek in Bayonne, where he plans to help revitalize an already growing community. And his background and skills, he firmly believes, position him uniquely for that task. Rabbi Unger’s own story starts in Bay Ridge in 1968, but he has roots in Hudson County. His maternal grandmother, Molly Safier, had a big brother, Shloimeh — it became Sam once he came to this country — who was born in 1869. “He is the oldest figure in the family, legendary, almost mythological,” Rabbi Unger said. In fact, he is known in family lore as Uncle Safier, never the less formal Uncle Sam. He was the carrier of the family name. “He had a big paper plant in Jersey City, and he lived in Hoboken,” Rabbi Unger said; he’s not sure what the plant was called, but he knows it was destroyed in a fire at some point, probably in the 1930s. -

A Taste of Torah Stories for the Soul the Loyal Friend by Rabbi Chaim Gross Night Classes Figuring out Where to Focus One’S Perfectly Honest

Parshas Naso May 21, 2021 A Taste of Torah Stories for the Soul The Loyal Friend by Rabbi Chaim Gross Night Classes Figuring out where to focus one’s perfectly honest. A newly-married yeshiva student attention and effort in life can be Then came the dreaded letter in the mail. studying in the Mir Yeshiva in challenging, especially when some things It seemed that the government suspected Brooklyn, NY was in the bais medrash seem more attractive. This lesson comes Moshe of a serious violation – one that nightly studying with his chavrusa through this week’s parsha. The verse could result in many a year behind bars, (study partner) until midnight. Rabbi (Bamidbar 5:10) states, “A man’s holies if not a lifetime sentence. He was being Shmuel Brudny (1915-1981), the Rosh shall be his, [and] that which a man gives summoned to court. Moshe desperately Yeshiva (Dean) of the Mir, approached to a kohen shall be his.” needed help, and he knew just whom the fellow and said, “I heard you are One phrase, repeated twice in this verse, to call. He reached for his phone and learning at night with so-and-so. Can catches the reader’s attention, as it is selected speed-dial #2 (#1 was his wife). I ask where you are studying?” strikingly ambiguous. We are told that The phone rang, and then he heard “In the yeshiva,” replied the newlywed. the items listed here, both a man’s holies his dear friend Dovid at the other end. “That’s wonderful,” said Rabbi as well as that which he gives to the kohen But the words were not what he had Brudny, “but it might be a better idea “shall be his.” To whom, exactly, do they expected.