From Yeshiva to Work the American Experience and Lessons for Israel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

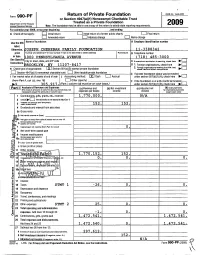

Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1 545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2009 I n t ernal R evenue Service Note . The foundation may be able to use a cony of this return to satisfy state reoortmo reaulrements. For calendar year 2009 , or tax year beginning , and ending G Check all that apply. Initial return 0 Initial return of a former public charity 0 Final return Amended return Address chanae 0 Name chanae Name of foundation A Employer identification number Use the IRS label. Otherwise , JOSEPH CHEHEBAR FAMILY FOUNDATION 11-3388342 print Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number ortype . 1000 PENNSYLVANIA AVENUE ( 718 ) 485-3000 See Specific City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending , check here ^ Instructions. BROOKLYN , NY 11207-8417 D I. Foreign organizations, check here 2. meeting s% test, H Check type of organization: ® Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation =are comp on 0 Section 4947(a )( 1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust 0 Other taxable private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: ® Cash 0 Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part Il, col (c), line 16) 1 Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month terminatio n 10- s 3 0 5 917. (Part 1, column (d) must be on cash basis.) under section 507( b )( 1 ) B), check here Part I Analysis of Revenue and Expenses (a) Revenue and (b ) Net investment (c) Adjusted net ( d) Disbursements (The total of amounts in columns (b). -

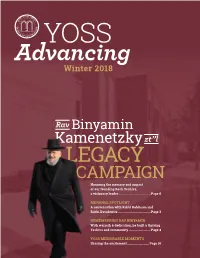

2018-YOSS-Advancing.Pdf

YOSS Advancing Winter 2018 Rav Binyamin Kamenetzky zt”l LEGACY CAMPAIGN Honoring the memory and impact of our founding Rosh Yeshiva, a visionary leader ...................................... Page 6 MENAHEL SPOTLIGHT A conversation with Rabbi Robinson and Rabbi Davidowitz ....................................... Page 3 REMEMBERING RAV BINYAMIN With warmth & dedication, he built a thriving Yeshiva and community .......................... Page 4 YOSS MEMORABLE MOMENTS Sharing the excitement .......................... Page 10 PAGE 2 MESSAGE FROM THE ROSH YESHIVA Sefer Shemos is the story of the emergence of Klal Yisrael from a small tribe of the progeny of Yaakov, to a thriving nation with millions of descendants, who accepted upon themselves the yoke of Torah. It is the story of a nation that went out to a desert and sowed the seeds of the future – a future that thrives to this very day. More than sixty years ago, my grandfather Rav Yaakov Kamenetzky, zt”l, charged my father and mother with the formidable task, “Go to the desert and plant the seeds of Torah.” What started as a fledgling school with six or seven boys, flourished more than a hundred fold. With institutions of tefilah, and higher Torah learning, all the outgrowth of that initial foray into the desert, my father’s impact is not only eternal but ever-expanding. This year’s dinner will mark both the commemoration of those accomplishments and a commitment to the renewal, refurbishment and expansion of the Torah facility he built brick by brick in 1964. Whether you are a student, an alumnus, a parent or community member, my father’s vision touched your life, and I hope that you will join us in honoring his. -

Till Death Do Us Part: the Halachic Prospects of Marriage for Conjoined (Siamese) Twins

259 ‘Till Death Do Us Part: The Halachic Prospects of Marriage for Conjoined (Siamese) Twins By: REUVEN CHAIM KLEIN There are many unknowns when it comes to discussions about Siamese twins. We do not know what causes the phenomenon of conjoined twins,1 we do not know what process determines how the twins will be conjoined, and we do not know why they are more common in girls than in boys. Why are thoracopagical twins (who are joined at the chest) the most com- mon type of conjoinment making up 75% of cases of Siamese twins,2 while craniopagus twins (who are connected at the head) are less com- mon? When it comes to integrating conjoined twins into greater society, an- other bevy of unknowns is unleashed: Are they one person or two? Could they get married?3 Can they be liable for corporal/capital punishment? Contemporary thought may have difficulty answering these questions, es- pecially the last three, which are not empirical inquiries. Fortunately, in 1 R. Yisroel Yehoshua Trunk of Kutna (1820–1893) claims that Jacob and Esau gestated within a shared amniotic sac in the womb of their mother Rebecca (as evidenced from the fact that Jacob came out grasping his older brother’s heel). As a result, there was a high risk that the twins would end up sticking together and developing as conjoined twins. In order to counter that possibility, G-d mi- raculously arranged for the twins to restlessly “run around” inside their mother’s womb (Gen. 25:22) in order that the two fetuses not stick together. -

Knights for Israel Honored at Camera Gala 2018 a Must-See Film

Editorials ..................................... 4A Op-Ed .......................................... 5A Calendar ...................................... 6A Scene Around ............................. 9A Synagogue Directory ................ 11A JTA News Briefs ........................ 13A WWW.HERITAGEFL.COM YEAR 42, NO. 40 JUNE 8, 2018 25 SIVAN, 5778 ORLANDO, FLORIDA SINGLE COPY 75¢ JNF’s Plant Your Way website NEW YORK—Jewish Na- it can be applied to any Jewish tional Fund revealed its new National Fund trip and the Plant Your Way website that Alexander Muss High School easily allows individuals to in Israel (AMHSI-JNF) is a raise money for a future trip huge bonus because donors to Israel while helping build can take advantage of the 100 the land of Israel. percent tax deductible status First introduced in 2000, of the contributions.” Plant Your Way has allowed Some of the benefits in- many hundreds of young clude: people a personal fundraising • Donations are 100 percent platform to raise money for a tax deductible; trip to Israel while giving back • It’s a great way to teach at the same time. Over the children and young adults the last 18 years, more than $1.3 basics of fundraising, while million has been generated for they build a connection to Jewish National Fund proj- Israel and plan a personal trip Knights for Israel members (l-r): Emily Aspinwall, Sam Busey, Jake Suster, Jesse Benjamin Slomowitz and Benji ects, typically by high school to Israel; Osterman, accepted the David Bar-Ilan Award for Outstanding Campus Activism. students. The new platform • Funds raised can be ap- allows parents/grandparents plied to any Israel trip (up to along with family, friends, age 30); coworkers and classmates • Participant can designate Knights for Israel honored to open Plant Your Way ac- to any of Jewish National counts for individuals from Fund’s seven program areas, birth up to the age of 30, and including forestry and green at Camera Gala 2018 for schools to raise money for innovation, water solutions, trips as well. -

PURIM-PAKS Will Deliver an Attractive Carry-Case Filled with Goodies Right in Time for Purim

s”xc If you have family or friends in 24 Years YERUSHALAYIM, TELZ-STONE of Satisfied OR BEIT SHEMESH… Customers! BRIGHTEN UP THEIR PURIM WITH OUR SHALACH MANOS! PURIM-PAKS will deliver an attractive carry-case filled with goodies right in time for Purim. Contents are in sealed packages with Badatz Eida HaCharedis Kosher supervision. Fill in the form (on reverse side) and send with $30.00 U.S. check by February 25, 2009 To: PURIM-PAKS, Apt. 308 17000 N.E. 14th Ave. North Miami Beach, FL 33162 More Info? Call Toll Free: 1-800-662-8280 (Please turn over) FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS What is in the Purim-Pak? Purim-Pak (shown) contains: a bottle of Pepsi, hamentashen, pretzels, potato chips, chocolate bar, onion crackers, banana chips, snack bar and noisemaker, all in a festive, zippered bag. Contents will be comparable to the picture. When will it be delivered? Delivery is between Taanis Esther and Purim. (For technical reasons, some may be delivered a day or two earlier.) Please note: Purim is celebrated in Yerushalayim after your Purim. Do you deliver to Betar, Bnei Brak, Haifa, Kiryat Sefer, Raanana, Tel Aviv? No. We deliver in Jerusalem, Telzstone and Beit Shemesh, plus to yeshivas in Beit Meir and Mevasseret Zion. Can I pay with a credit card? No, sorry! Please send check drawn on U.S. bank - $30 includes delivery! I only have a box # for an address. What shall I do? We do not deliver to post office boxes. However, if the P.O. box is for a Yeshiva or Sem student, we can verify the school’s street address. -

Pirchei Agudas Yisroel of America

בס״ד בס״ד Learning from our Leaders Pirchei Agudas Yisroel of America RavOne Ben time Tzion R’ SegalAbba Shaulneeded was to thego Rosh Yeshiva As they approached their assignedRabbeinu! seats... in Yeshivatto Gateshead Porat withYosef his in son. Yerushalayim. One Someone accidentally afternoon Rav Mutzafi approached him with an padlocked the kitchen door emergency while he was learning. Tatty, but that’s I can’t learn Pesach,with please all the food for tonight’s PIRCHEI Two Adult 2nd cost so much more… hmm that small with this let’s movemeal. to How are we going to class tickets especially for 2 Agudas Yisroel of America boy easily could noise. the first classfeed our 120 hungry Vol: 6 Issue: 18 - י"א אדר א', תשע"ט - please. pass as a child… compartment. Bachurimadults!? February 9, 2019 פרשה: תצוה הפטרה: אתה בן אדם... )יחזקאל מג:י-כז( !!! eyi purho prhhkfi t canjv!!! nrcho tsr nabfbx tsr דף יומי: חולין פ״א מצות עשה: 4 מצות לא תעשה: 3 TorahThoughts was during this time, but מ ֹ ׁשֶ ה There are differing opinions as to where) וְעָשִׂ יתָבִׂגְדֵ יקֹדֶ ׁש לְאַ הֲרֹן ... לְכָבֹודּולְתִׂ פְאָרֶ ת)ׁשְ מֹות כח:ב(. Immediately Rabbi Abba Shaul took all The trainMoshe, attendant Chaim, Don inexplicably and Yosef! did You It is worthwhile to your , אַ הֲ ֹר ן the money he had out of his pocket. allnot can show share up into the collect privilege tickets. of a special And you shall make garments of sanctity for spend extra money for he certainly was not in Egypt.) mitzvah. -

Vertientes Del Judaismo #3

CLASES DE JUDAISMO VERTIENTES DEL JUDAISMO #3 Por: Eliyahu BaYonah Director Shalom Haverim Org New York Vertientes del Judaismo • LA ORTODOXIA MODERNA • La Ortodoxia moderna comprende un espectro bastante amplio de movimientos, cada extracción toma varias filosofías aunque relacionados distintamente, que en alguna combinación han proporcionado la base para todas las variaciones del movimiento de hoy en día. • En general, la ortodoxia moderna sostiene que la ley judía es normativa y vinculante, y concede al mismo tiempo un valor positivo para la interacción con la sociedad contemporánea. Vertientes del Judaismo • LA ORTODOXIA MODERNA • En este punto de vista, el judaísmo ortodoxo puede "ser enriquecido" por su intersección con la modernidad. • Además, "la sociedad moderna crea oportunidades para ser ciudadanos productivos que participan en la obra divina de la transformación del mundo en beneficio de la humanidad". • Al mismo tiempo, con el fin de preservar la integridad de la Halajá, cualquier área de “fuerte inconsistencia y conflicto" entre la Torá y la cultura moderna debe ser evitada. La ortodoxia moderna, además, asigna un papel central al "Pueblo de Israel " Vertientes del Judaismo • LA ORTODOXIA MODERNA • La ortodoxia moderna, como una corriente del judaísmo ortodoxo representado por instituciones como el Consejo Nacional para la Juventud Israel, en Estados Unidos, es pro-sionista y por lo tanto da un estatus nacional, así como religioso, de mucha importancia en el Estado de Israel, y sus afiliados que son, por lo general, sionistas en la orientación. • También practica la implicación con Judíos no ortodoxos que se extiende más allá de "extensión (kiruv)" a las relaciones institucionales y la cooperación continua, visto como Torá Umaddá. -

Dear Youth Directors, Youth Chairs, and Youth Leaders, NCYI Is Excited to Continue Our Very Successful Parsha Nation Guides

Dear Youth Directors, Youth chairs, and Youth Leaders, NCYI is excited to continue our very successful Parsha Nation Guides. I hope you’re enjoying and learning from Parsha Nation as much as we are. Putting together Parsha Nation every week is indeed no easy task. It takes a lot of time and effort to ensure that each section, as well as each age group, receives the attention and dedication it deserves. We inspire and mold future leaders. The youth leaders of Young Israel have the distinct honor and privilege to teach and develop the youth of Young Israel. Children today are constantly looking for role models and inspirations to latch on to and learn from. Whether it is actual sit down learning sessions, exciting Parsha trivia games, or even just walking down the hall to the Kiddush room, our youth look to us and watch our every move. It’s not always about the things we say, it’s about the things we do. Our children hear and see everything we do whether we realize it or not. This year we are taking our Youth Services to new heights as we introduce our Leadership Training Shabbaton. This engaging, interactive shabbaton will give youth leader’s hands on experience and practical solutions to effectively guide your youth department. Informal education is key. What the summer shows us as educators is that informal education can deliver better results and help increase our youth’s connection to Hashem. More and more shuls are revamping their youth program to give their children a better connection to shul and to Hashem. -

A Japanese Righteous Gentile: the Sugihara Case1

Chapter 10 A Japanese Righteous Gentile: The Sugihara Case1 In the Avenue of the Righteous Gentiles in the Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial in Jerusalem, Japan is represented by one individual deemed worthy to be included: a man who helped some 6,000 Jews escape from Lithuania in the summer of 1940. His name was Vice Consul Sugihara Chiune (or Sugihara Sempo), who granted transit visas to Japan to some two thousand, six hundred Polish and Lithuanian Jewish families, thus saving them from either probable extermination by the Germans or pro- longed incarceration or Siberian exile by the Soviets. Sugihara would have remained a footnote in history were it not for his efforts, made—as it was later claimed—without the prior approval of, and at times without the knowledge of, his superiors in Tokyo. It is hard to determine what led Sugihara to help Jews, and to what extent he was aware that he would earn a place in Jewish history. Apart from him and Vice Consul Shibata in Shanghai, who alerted the Jewish community in that city to the Meisinger scheme, Japanese civilian or mil- itary officials did not go out of their ways to help Jews, probably because there was no need to. We have already noted that the Japanese government and military had no intention of liquidating the Jews in the territories under their control and consistently rejected German requests that they do so. What led Japan to act the way it did was not the result of any concern for the Jews but rather the result of cool and calculated considerations. -

The 5 Towns Jewish Times! You Can Upload Your Digital Photos and See Them Printed in the Weekly Edition of the 5 Towns Jewish Times

$1.00 WWW.5TJT.COM VOL. 8 NO. 34 11 IYAR 5768 rvc ,arp MAY 16, 2008 INSIDE FROM THE EDITOR’S DESK A BIG 60TH BIRTHDAY BASH MindBiz B Y LARRY GORDON Esther Mann, LMSW 34 Clothes Make The Man Calm By Force Votes Needed Hannah Reich Berman 52 Letters To The Editor The above headline School Board Elections, Our Readers 62 reminds me of oxymoronic May 20 phrases that are frequently It is as quiet an election as PhotoByJerr Stagflation used—things like “more quiet” it is a key election. Perhaps Martin Mushell 66 or “trying to rest.” Perhaps more than any other entities, yMeyerStudio that’s the best way to describe the local newspapers are suf- David Or Bush? the fashion in which today’s fering because, at least up David Wilder 79 Israel is being governed. It’s until this week, there have Among the many events celebrating Israel’s 60th anniversary was a very about definitive ambiguities been no “The sky is going to special appearance by Israel’s Ashkenazic chief rabbi, Rabbi Yona Metzger, and agreeable contradictions. fall if you don’t vote against who spoke last weekend at the Young Israel of Hewlett. A capacity crowd was present at each of the rabbi’s lectures. Pictured above (L–R): Rabbi Pesach Perhaps it was during a the private schools!” ads in Lerner of the National Council of Young Israel; Rabbi Heshy Blumstein, rabbi of Young Israel of Hewlett; Rabbi Metzger; and Charles Miller, Continued on Page 6 Continued on Page 16 president of the Young Israel. -

Maspidim Remember Klal Yisroel's Rebbe, the Novominsker Rebbe

Maspidim Remember Klal Yisroel’s Rebbe, The Novominsker Rebbe April 29, 2020 See the recording of the azkarah below. By: Sandy Eller Harav Elya Brudny, Rosh Yeshiva, Mir Yeshiva and Chaver Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah 22 days later it still seems impossible to believe. As Klal Yisroel continues to mourn the loss of the Novominsker Rebbe, Rabbi Yaakov Perlow ztvk’l, Rosh Agudas Yisroel, chaverim of the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah and family members offered deeply emotional divrei hesped for a leader who was a major guiding force for Torah Jewry in America for decades. With state and local laws still in effect prohibiting public gatherings, maspidim addressed an empty beis medrash at Yeshivas Novominsk, an audience of nearly 60,000 listening through teleconference and livestream as the Novominsker was remembered as Klal Yisroel’s Rebbe. Normally echoing with exuberant sounds oftalmidim learning Torah, the yeshiva’s stark emptiness was yet another painful reminder of the present eis tzarah that has devastated our community. Rabbi Zwiebel waiting at a safe social distance while others were speaking. Throughout the over two hour-long azkarah, Rabbi Perlow was lauded for his unwavering devotion to Klal Yisroel, somehow stretching the hours of each day so that he could immerse himself in his learning and still give his undivided attention to the many organizations and individuals who sought his guidance. In a pre-recorded segment, Rabbi Shmuel Kamenetsky, Rosh HaYeshiva, Talmudical Yeshiva of Philadelphia, described the Rebbe as a “yochid b’yisroel” who cared so deeply for others that their needs became his. No communal issue was deemed too large, too small, or beyond the Novominsker’s realm of expertise, his sage counsel steering Klal Yisroel through turbulent waters when communal institutions such asbris milah, shechitah and yeshiva curriculums were threatened by public officials. -

Cincinnati Torah הרות

בס"ד • A PROJECT OF THE CINCINNATI COMMUNITY KOLLEL • CINCYKOLLEL.ORG תורה מסינסי Cincinnati Torah Vol. VIII, No. XIX Ki Sisa A LESSON FROM THE PARASHA A TIMELY HALACHA RABBI CHAIM HEINEMANN To Life and Beyond GUEST CONTRIBUTOR During the time the Beis Hamikdash SHMUEL BOTNICK (the Holy Temple) existed, our Sages enacted that Torah scholars should “After all, to the well-organized mind, death is but miraculously revitalized. Somehow, the lecture publicly on the laws related the next great adventure.” decree in Heaven that the Jewish people be to each festival thirty days before the Professor Albus Dumbledore* destroyed was issued with such potency that, festival. Therefore, beginning Purim, our on a spiritual dimension, it is as if it actually rabbis should teach the laws of Pesach. I’m no talmid of Dumbledore’s (the Sorting happened. The miracle, therefore, was one in Hat sent me off to Brisk), but you gotta give The source for this is that Moshe stood which we transition from the throes of death right before Pesach and taught the laws him credit when it’s due. Though the quote to a newly acquired, freshly rejuvanated, life. excerpted above is surely cloaked with layers of Pesach Sheini (a makeup offering on of esoteric meaning, for our purposes, I’d If this concept seems abstract, it needn’t the 15th of Iyar for those who were unfit earlier). like to discuss how it goes to the very heart of be. Its message is fully relevant. On Purim Though there are Purim’s essence and the focus of our avodah we were imbued with a new breath of life, those who want to suggest, based on the above, that this obligation is (service) in the days that follow.