Bayonne's Rabbi with a Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New York CITY

New York CITY the 123rd Annual Meeting American Historical Association NONPROFIT ORG. 400 A Street, S.E. U.S. Postage Washington, D.C. 20003-3889 PAID WALDORF, MD PERMIT No. 56 ASHGATENew History Titles from Ashgate Publishing… The Chronicle of Ibn al-Athir The Long Morning of Medieval Europe for the Crusading Period New Directions in Early Medieval Studies Edited by Jennifer R. Davis, California Institute from al-Kamil fi’l-Ta’rikh. Part 3 of Technology and Michael McCormick, The Years 589–629/1193–1231: The Ayyubids Harvard University after Saladin and the Mongol Menace Includes 25 b&w illustrations Translated by D.S. Richards, University of Oxford, UK June 2008. 366 pages. Hbk. 978-0-7546-6254-9 Crusade Texts in Translation: 17 June 2008. 344 pages. Hbk. 978-0-7546-4079-0 The Art, Science, and Technology of Medieval Travel The Portfolio of Villard de Honnecourt Edited by Robert Bork, University of Iowa (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale and Andrea Kann AVISTA Studies in the History de France, MS Fr 19093) of Medieval Technology, Science and Art: 6 A New Critical Edition and Color Facsimile Includes 23 b&w illustrations with a glossary by Stacey L. Hahn October 2008. 240 pages. Hbk. 978-0-7546-6307-2 Carl F. Barnes, Jr., Oakland University Includes 72 color and 48 b&w illustrations November 2008. 350 pages. Hbk. 978-0-7546-5102-4 The Medieval Account Books of the Mercers of London Patents, Pictures and Patronage An Edition and Translation John Day and the Tudor Book Trade Lisa Jefferson Elizabeth Evenden, Newnham College, November 2008. -

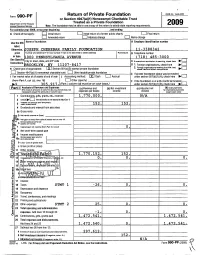

Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1 545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2009 I n t ernal R evenue Service Note . The foundation may be able to use a cony of this return to satisfy state reoortmo reaulrements. For calendar year 2009 , or tax year beginning , and ending G Check all that apply. Initial return 0 Initial return of a former public charity 0 Final return Amended return Address chanae 0 Name chanae Name of foundation A Employer identification number Use the IRS label. Otherwise , JOSEPH CHEHEBAR FAMILY FOUNDATION 11-3388342 print Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number ortype . 1000 PENNSYLVANIA AVENUE ( 718 ) 485-3000 See Specific City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending , check here ^ Instructions. BROOKLYN , NY 11207-8417 D I. Foreign organizations, check here 2. meeting s% test, H Check type of organization: ® Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation =are comp on 0 Section 4947(a )( 1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust 0 Other taxable private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: ® Cash 0 Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part Il, col (c), line 16) 1 Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month terminatio n 10- s 3 0 5 917. (Part 1, column (d) must be on cash basis.) under section 507( b )( 1 ) B), check here Part I Analysis of Revenue and Expenses (a) Revenue and (b ) Net investment (c) Adjusted net ( d) Disbursements (The total of amounts in columns (b). -

2018-YOSS-Advancing.Pdf

YOSS Advancing Winter 2018 Rav Binyamin Kamenetzky zt”l LEGACY CAMPAIGN Honoring the memory and impact of our founding Rosh Yeshiva, a visionary leader ...................................... Page 6 MENAHEL SPOTLIGHT A conversation with Rabbi Robinson and Rabbi Davidowitz ....................................... Page 3 REMEMBERING RAV BINYAMIN With warmth & dedication, he built a thriving Yeshiva and community .......................... Page 4 YOSS MEMORABLE MOMENTS Sharing the excitement .......................... Page 10 PAGE 2 MESSAGE FROM THE ROSH YESHIVA Sefer Shemos is the story of the emergence of Klal Yisrael from a small tribe of the progeny of Yaakov, to a thriving nation with millions of descendants, who accepted upon themselves the yoke of Torah. It is the story of a nation that went out to a desert and sowed the seeds of the future – a future that thrives to this very day. More than sixty years ago, my grandfather Rav Yaakov Kamenetzky, zt”l, charged my father and mother with the formidable task, “Go to the desert and plant the seeds of Torah.” What started as a fledgling school with six or seven boys, flourished more than a hundred fold. With institutions of tefilah, and higher Torah learning, all the outgrowth of that initial foray into the desert, my father’s impact is not only eternal but ever-expanding. This year’s dinner will mark both the commemoration of those accomplishments and a commitment to the renewal, refurbishment and expansion of the Torah facility he built brick by brick in 1964. Whether you are a student, an alumnus, a parent or community member, my father’s vision touched your life, and I hope that you will join us in honoring his. -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St. -

51 White Street

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION December 19, 2018 / Calendar No. 13 C 180439 ZSM IN THE MATTER OF an application submitted by 51 White Street LLC pursuant to Sections 197-c and 201 of the New York City Charter for the grant of a special permit pursuant to Section 74-711 of the Zoning Resolution to modify the height and setback requirements of Section 23-662 (Maximum height of buildings and setback regulations) and Section 23-692 (Height limitations for narrow buildings or enlargements), the inner court requirements of Section 23-85 (Inner Court Regulations) and the minimum distance between legally required windows and walls or lot lines requirements of Section 23-86 (Minimum Distance Between Legally Required Windows and Walls or Lot Lines), to facilitate the vertical enlargement of an existing 5 story building, on property located at 51 White Street (Block 175, Lot 24), in a C6-2A District, within the Tribeca East Historic District, Borough of Manhattan, Community District 1. This application for a special permit was filed by 51 White Street LLC on May 17, 2018. The requested special permit would facilitate a two-story vertical enlargement of an existing five-story building, and the introduction of a new mezzanine level between existing first and second floors, at 51 White Street in the Tribeca neighborhood of Manhattan. BACKGROUND The applicant requests bulk waivers to facilitate the enlargement of an existing building in the Tribeca East Historic District in Manhattan Community District 1. 51 White Street is located on the south side of White Street, between Broadway and Church Street. -

Pirchei Agudas Yisroel of America

בס״ד בס״ד Learning from our Leaders Pirchei Agudas Yisroel of America RavOne Ben time Tzion R’ SegalAbba Shaulneeded was to thego Rosh Yeshiva As they approached their assignedRabbeinu! seats... in Yeshivatto Gateshead Porat withYosef his in son. Yerushalayim. One Someone accidentally afternoon Rav Mutzafi approached him with an padlocked the kitchen door emergency while he was learning. Tatty, but that’s I can’t learn Pesach,with please all the food for tonight’s PIRCHEI Two Adult 2nd cost so much more… hmm that small with this let’s movemeal. to How are we going to class tickets especially for 2 Agudas Yisroel of America boy easily could noise. the first classfeed our 120 hungry Vol: 6 Issue: 18 - י"א אדר א', תשע"ט - please. pass as a child… compartment. Bachurimadults!? February 9, 2019 פרשה: תצוה הפטרה: אתה בן אדם... )יחזקאל מג:י-כז( !!! eyi purho prhhkfi t canjv!!! nrcho tsr nabfbx tsr דף יומי: חולין פ״א מצות עשה: 4 מצות לא תעשה: 3 TorahThoughts was during this time, but מ ֹ ׁשֶ ה There are differing opinions as to where) וְעָשִׂ יתָבִׂגְדֵ יקֹדֶ ׁש לְאַ הֲרֹן ... לְכָבֹודּולְתִׂ פְאָרֶ ת)ׁשְ מֹות כח:ב(. Immediately Rabbi Abba Shaul took all The trainMoshe, attendant Chaim, Don inexplicably and Yosef! did You It is worthwhile to your , אַ הֲ ֹר ן the money he had out of his pocket. allnot can show share up into the collect privilege tickets. of a special And you shall make garments of sanctity for spend extra money for he certainly was not in Egypt.) mitzvah. -

Dear Youth Directors, Youth Chairs, and Youth Leaders, NCYI Is Excited to Continue Our Very Successful Parsha Nation Guides

Dear Youth Directors, Youth chairs, and Youth Leaders, NCYI is excited to continue our very successful Parsha Nation Guides. I hope you’re enjoying and learning from Parsha Nation as much as we are. Putting together Parsha Nation every week is indeed no easy task. It takes a lot of time and effort to ensure that each section, as well as each age group, receives the attention and dedication it deserves. We inspire and mold future leaders. The youth leaders of Young Israel have the distinct honor and privilege to teach and develop the youth of Young Israel. Children today are constantly looking for role models and inspirations to latch on to and learn from. Whether it is actual sit down learning sessions, exciting Parsha trivia games, or even just walking down the hall to the Kiddush room, our youth look to us and watch our every move. It’s not always about the things we say, it’s about the things we do. Our children hear and see everything we do whether we realize it or not. This year we are taking our Youth Services to new heights as we introduce our Leadership Training Shabbaton. This engaging, interactive shabbaton will give youth leader’s hands on experience and practical solutions to effectively guide your youth department. Informal education is key. What the summer shows us as educators is that informal education can deliver better results and help increase our youth’s connection to Hashem. More and more shuls are revamping their youth program to give their children a better connection to shul and to Hashem. -

Gns2016 Scope Rh 2016 1 שנה טובה!

Great Neck Synagogue Magazine S|C|O|P|E Rosh Hashanah2016 Tishrei5777 on to Treasures from the Cairo Geniza By Dr. Arnold Breitbart | Generation to Generation to | Generation Was It the Right Choice By Rabbi Moshe Kwalbrun AIPAC Policy Conference 2016 By Michele Wolf Mazel Tov to our Simchat Torah honorees! Chatan Torah: Aryeh Family Chatan Breishit: Howard Silberstein Chatan Maftir: Mark Gelberg | Generation to Generation | Generation to | Generation GNS2016 SCOPE RH 2016 1 שנה טובה! May this year be filled with sweetness, happiness, and simcha! From Your Favorite Glatt Kosher Caterer! Taste The Exceptional Great Neck Synagogue ∎brit Milahs ∎engagements ∎luncheons ∎bridal showers ∎bar/bat mitzvah ∎Weddings Book Now: 516-466-2222 SCOPE RH 2016 2 Great Neck Synagogue Magazine Great Neck Synagogue GNS2016 S|C|O|P|E 26 Old Mill Road Great Neck, NY 11023 Rosh Hashanah Issue | 2016 Table of Contents T: 516 487 6100 www.gns.org Excerpt From the Upcoming Book The Brooklyn Nobody Knows By William B. Helmreich p.12 Dale E. Polakoff, Rabbi Ian Lichter, Assistant Rabbi Was It The Right Choice By Rabbi Moshe Kwalbrun p.14 Ze’ev Kron, Cantor Mark Twersky, Executive Director A Black and White World By Annie Karpenstein p.15 James Frisch, Assistant Executive Director Sholom Jensen, Rabbi, Youth Director Jerusalem My Inspiration By Susan Goldstein p.18 Dr. Michael & Zehava Atlas, Youth Directors Lisa Septimus, Yoetzet Halacha “Say Little and Do Much” – “A Few Word but Many Deeds” Dr. Ephraim Wolf, z”l, Rabbi Emeritus By Zachary Dicker p.19 Eleazer Schulman, z”l, Cantor Emeritus Treasures from the Cairo Geniza By Dr. -

A Japanese Righteous Gentile: the Sugihara Case1

Chapter 10 A Japanese Righteous Gentile: The Sugihara Case1 In the Avenue of the Righteous Gentiles in the Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial in Jerusalem, Japan is represented by one individual deemed worthy to be included: a man who helped some 6,000 Jews escape from Lithuania in the summer of 1940. His name was Vice Consul Sugihara Chiune (or Sugihara Sempo), who granted transit visas to Japan to some two thousand, six hundred Polish and Lithuanian Jewish families, thus saving them from either probable extermination by the Germans or pro- longed incarceration or Siberian exile by the Soviets. Sugihara would have remained a footnote in history were it not for his efforts, made—as it was later claimed—without the prior approval of, and at times without the knowledge of, his superiors in Tokyo. It is hard to determine what led Sugihara to help Jews, and to what extent he was aware that he would earn a place in Jewish history. Apart from him and Vice Consul Shibata in Shanghai, who alerted the Jewish community in that city to the Meisinger scheme, Japanese civilian or mil- itary officials did not go out of their ways to help Jews, probably because there was no need to. We have already noted that the Japanese government and military had no intention of liquidating the Jews in the territories under their control and consistently rejected German requests that they do so. What led Japan to act the way it did was not the result of any concern for the Jews but rather the result of cool and calculated considerations. -

Guide to the Department of Buildings Architectural Drawings and Plans for Lower Manhattan, Circa 1866-1978 Collection No

NEW YORK CITY MUNICIPAL ARCHIVES 31 CHAMBERS ST., NEW YORK, NY 10007 Guide to the Department of Buildings architectural drawings and plans for Lower Manhattan, circa 1866-1978 Collection No. REC 0074 Processing, description, and rehousing by the Rolled Building Plans Project Team (2018-ongoing): Amy Stecher, Porscha Williams Fuller, David Mathurin, Clare Manias, Cynthia Brenwall. Finding aid written by Amy Stecher in May 2020. NYC Municipal Archives Guide to the Department of Buildings architectural drawings and plans for Lower Manhattan, circa 1866-1978 1 NYC Municipal Archives Guide to the Department of Buildings architectural drawings and plans for Lower Manhattan, circa 1866-1978 Summary Record Group: RG 025: Department of Buildings Title of the Collection: Department of Buildings architectural drawings and plans for Lower Manhattan Creator(s): Manhattan (New York, N.Y.). Bureau of Buildings; Manhattan (New York, N.Y.). Department of Buildings; New York (N.Y.). Department of Buildings; New York (N.Y.). Department of Housing and Buildings; New York (N.Y.). Department for the Survey and Inspection of Buildings; New York (N.Y.). Fire Department. Bureau of Inspection of Buildings; New York (N.Y.). Tenement House Department Date: circa 1866-1978 Abstract: The Department of Buildings requires the filing of applications and supporting material for permits to construct or alter buildings in New York City. This collection contains the plans and drawings filed with the Department of Buildings between 1866-1978, for the buildings on all 958 blocks of Lower Manhattan, from the Battery to 34th Street, as well as a small quantity of material for blocks outside that area. -

Maspidim Remember Klal Yisroel's Rebbe, the Novominsker Rebbe

Maspidim Remember Klal Yisroel’s Rebbe, The Novominsker Rebbe April 29, 2020 See the recording of the azkarah below. By: Sandy Eller Harav Elya Brudny, Rosh Yeshiva, Mir Yeshiva and Chaver Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah 22 days later it still seems impossible to believe. As Klal Yisroel continues to mourn the loss of the Novominsker Rebbe, Rabbi Yaakov Perlow ztvk’l, Rosh Agudas Yisroel, chaverim of the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah and family members offered deeply emotional divrei hesped for a leader who was a major guiding force for Torah Jewry in America for decades. With state and local laws still in effect prohibiting public gatherings, maspidim addressed an empty beis medrash at Yeshivas Novominsk, an audience of nearly 60,000 listening through teleconference and livestream as the Novominsker was remembered as Klal Yisroel’s Rebbe. Normally echoing with exuberant sounds oftalmidim learning Torah, the yeshiva’s stark emptiness was yet another painful reminder of the present eis tzarah that has devastated our community. Rabbi Zwiebel waiting at a safe social distance while others were speaking. Throughout the over two hour-long azkarah, Rabbi Perlow was lauded for his unwavering devotion to Klal Yisroel, somehow stretching the hours of each day so that he could immerse himself in his learning and still give his undivided attention to the many organizations and individuals who sought his guidance. In a pre-recorded segment, Rabbi Shmuel Kamenetsky, Rosh HaYeshiva, Talmudical Yeshiva of Philadelphia, described the Rebbe as a “yochid b’yisroel” who cared so deeply for others that their needs became his. No communal issue was deemed too large, too small, or beyond the Novominsker’s realm of expertise, his sage counsel steering Klal Yisroel through turbulent waters when communal institutions such asbris milah, shechitah and yeshiva curriculums were threatened by public officials. -

Cincinnati Torah הרות

בס"ד • A PROJECT OF THE CINCINNATI COMMUNITY KOLLEL • CINCYKOLLEL.ORG תורה מסינסי Cincinnati Torah Vol. VIII, No. XIX Ki Sisa A LESSON FROM THE PARASHA A TIMELY HALACHA RABBI CHAIM HEINEMANN To Life and Beyond GUEST CONTRIBUTOR During the time the Beis Hamikdash SHMUEL BOTNICK (the Holy Temple) existed, our Sages enacted that Torah scholars should “After all, to the well-organized mind, death is but miraculously revitalized. Somehow, the lecture publicly on the laws related the next great adventure.” decree in Heaven that the Jewish people be to each festival thirty days before the Professor Albus Dumbledore* destroyed was issued with such potency that, festival. Therefore, beginning Purim, our on a spiritual dimension, it is as if it actually rabbis should teach the laws of Pesach. I’m no talmid of Dumbledore’s (the Sorting happened. The miracle, therefore, was one in Hat sent me off to Brisk), but you gotta give The source for this is that Moshe stood which we transition from the throes of death right before Pesach and taught the laws him credit when it’s due. Though the quote to a newly acquired, freshly rejuvanated, life. excerpted above is surely cloaked with layers of Pesach Sheini (a makeup offering on of esoteric meaning, for our purposes, I’d If this concept seems abstract, it needn’t the 15th of Iyar for those who were unfit earlier). like to discuss how it goes to the very heart of be. Its message is fully relevant. On Purim Though there are Purim’s essence and the focus of our avodah we were imbued with a new breath of life, those who want to suggest, based on the above, that this obligation is (service) in the days that follow.