A Japanese Righteous Gentile: the Sugihara Case1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Internationale Turniere B-Kategorie Spesenbeitrag Max

A-Kategorie Spesenersatz ÖBV Grundlagen für die Einsatzplanung österr. Schiedsrichter - Internationale Turniere B-Kategorie Spesenbeitrag max. € 200.- Die Beschickung erfolgt grundsätzlich nur durch das Schiedsrichterreferat (SRR) ! R……….Referee C-Kategorie Spesenbeitrag max. € 150.- U……….Umpire bestätigt vorgemerkt abgesagt D-Kategorie kein Spesenbeitrag Basis ist eine vorliegende Einladung für das Turnier, die Kategorie und die Qualifikation des SR`s A……….Assessor E ….. BEC-Event Spesenersatz ÖBV, Beitrag von BEC € 200.- N…national, I…international, BEC…Badminton Europe Confederation a/c, BWF…Badminton World Federation a/c. a…Assessment/Appraisal Participant F ….. BWF-Event Spesenersatz ÖBV (Interkontinental max. 50%) (T)…mögliches Trainingsturnier für Kandidaten zum Intern. SR in Begleitung eines erfahrenen Intern. SR`s C……..Course Instructor G ….. BWF-Event Spesenübernahme BWF Die Kollegen sind höflichst aufgefordert Ihre Einsätzewünsche dem SRR rasch bekannt zu geben. c……..Course Participant JA-JD ….. BEC-Junior Kategorien A-D wie oben beschrieben Die Zahlen geben die letzte Stelle des Jahres an, in dem das Turnier zuletzt besucht wurde (unabhängig von der Funktion). Einsätze die mehr als 10 Jahre zurückliegen werden nicht berücksichtigt. Season Date Tournament Venue Status Invitation Category Requirement Delegation Yes/No Personal Closing Minimum Course Date Level 2021 Assessment Appraisal Schwerin David BWFc-Ref.- BWFc - CejnekBWFa-Ref. Ewald - NemecItric Katarina Michael - BECcSchlieben KlausShahhosseini - BECc SaraWolf - BECcDaniel - BECcBöhm Andreas -Herbst BECa Miriam - KöchelhuberBECa ThomasSteiner - BECaMichael Eckersberger- BECa MarkusKleindienst ClaudioMittermayr LukasPfeffer-Jaoul ClaireRudolf Britta Steurer Fabian Svoboda MichaelWetz Peter Jan-21 11.-16.01.2021 BWF World Junior Team Championships 2020 cancelled Auckland/NZL BWF - Grade 1 G BWF 9 6 12.-17.01.2021 Asia Open 1 new date Bangkok/THA BWF - Super 1000 N G BWF 14.-17.01.2021 Estonia International cancelled Tallinn/EST BEC - Int. -

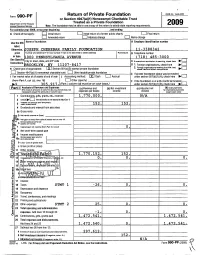

Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1 545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2009 I n t ernal R evenue Service Note . The foundation may be able to use a cony of this return to satisfy state reoortmo reaulrements. For calendar year 2009 , or tax year beginning , and ending G Check all that apply. Initial return 0 Initial return of a former public charity 0 Final return Amended return Address chanae 0 Name chanae Name of foundation A Employer identification number Use the IRS label. Otherwise , JOSEPH CHEHEBAR FAMILY FOUNDATION 11-3388342 print Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number ortype . 1000 PENNSYLVANIA AVENUE ( 718 ) 485-3000 See Specific City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending , check here ^ Instructions. BROOKLYN , NY 11207-8417 D I. Foreign organizations, check here 2. meeting s% test, H Check type of organization: ® Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation =are comp on 0 Section 4947(a )( 1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust 0 Other taxable private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: ® Cash 0 Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part Il, col (c), line 16) 1 Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month terminatio n 10- s 3 0 5 917. (Part 1, column (d) must be on cash basis.) under section 507( b )( 1 ) B), check here Part I Analysis of Revenue and Expenses (a) Revenue and (b ) Net investment (c) Adjusted net ( d) Disbursements (The total of amounts in columns (b). -

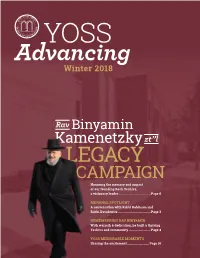

2018-YOSS-Advancing.Pdf

YOSS Advancing Winter 2018 Rav Binyamin Kamenetzky zt”l LEGACY CAMPAIGN Honoring the memory and impact of our founding Rosh Yeshiva, a visionary leader ...................................... Page 6 MENAHEL SPOTLIGHT A conversation with Rabbi Robinson and Rabbi Davidowitz ....................................... Page 3 REMEMBERING RAV BINYAMIN With warmth & dedication, he built a thriving Yeshiva and community .......................... Page 4 YOSS MEMORABLE MOMENTS Sharing the excitement .......................... Page 10 PAGE 2 MESSAGE FROM THE ROSH YESHIVA Sefer Shemos is the story of the emergence of Klal Yisrael from a small tribe of the progeny of Yaakov, to a thriving nation with millions of descendants, who accepted upon themselves the yoke of Torah. It is the story of a nation that went out to a desert and sowed the seeds of the future – a future that thrives to this very day. More than sixty years ago, my grandfather Rav Yaakov Kamenetzky, zt”l, charged my father and mother with the formidable task, “Go to the desert and plant the seeds of Torah.” What started as a fledgling school with six or seven boys, flourished more than a hundred fold. With institutions of tefilah, and higher Torah learning, all the outgrowth of that initial foray into the desert, my father’s impact is not only eternal but ever-expanding. This year’s dinner will mark both the commemoration of those accomplishments and a commitment to the renewal, refurbishment and expansion of the Torah facility he built brick by brick in 1964. Whether you are a student, an alumnus, a parent or community member, my father’s vision touched your life, and I hope that you will join us in honoring his. -

BADMINTON EUROPE JUNIOR CIRCUIT Regulations

BADMINTON EUROPE JUNIOR CIRCUIT Regulations 1. Description 1.1 The Badminton Europe Confederation (BEC) Junior Circuit is a series of international tournaments open to all badminton players under 19 years of age throughout the respective calendar year who are eligible to play for BWF Members. 1.2 The referee shall have the power to check the player’s age at any time. This can be done on the referee’s own initiative or by request from a third party. Photo identification (e.g. passport) is considered as being valid documentation for age check. If the referee discovers that a player breaches the age limit defined in § 1.1, such a player shall be penalised by disqualification, removal of ranking points and return of awarded prizes. 1.3 Players from European Members earn points for the BEC Junior Circuit Ranking according to the classification of the tournaments in accordance with § 4.1. 2. Organisation and responsibility 2.1 A BEC Junior Circuit tournament may be organised by a group of individuals a club or some other specific body (private or corporate), but the Member must have the ultimate authority and is liable under BADMINTON EUROPE Disciplinary Regulations to ensure that the tournament is run in a satisfactory manner and in accordance with these BEC Junior Circuit Regulations and BWF Regulations. 2.2 Any Member failing to comply with these BEC Junior Circuit Regulations may be penalised following the BADMINTON EUROPE’S Disciplinary Regulations. The possible penalties shall be: administrative fines, a fine of up to 5.000,00 EUR, withdrawal of sanction. -

The Signatories of the Israel Declaration of Independence

Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs The Signatories of the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel The British Mandate over Palestine was due to end on May 15, 1948, some six months after the United Nations had voted to partition Palestine into two states: one for the Jews, the other for the Arabs. While the Jews celebrated the United Nations resolution, feeling that a truncated state was better than none, the Arab countries rejected the plan, and irregular attacks of local Arabs on the Jewish population of the country began immediately after the resolution. In the United Nations, the US and other countries tried to prevent or postpone the establishment of a state, suggesting trusteeship, among other proposals. But by the time the British Mandate was due to end, the United Nations had not yet approved any alternate plan; officially, the partition plan was still "on the books." A dilemma faced the leaders of the yishuv, the Jewish community in Palestine. Should they declare the country's independence upon the withdrawal of the British mandatory administration, despite the threat of an impending attack by Arab states? Or should they wait, perhaps only a month or two, until conditions were more favorable? Under the leadership of David Ben-Gurion, who was to become the first Prime Minister of Israel, theVa'ad Leumi - the representative body of the yishuv under the British mandate - decided to seize the opportunity. At 4:00 PM on Friday, May 14, the national council, which had directed the Jewish community's affairs under the British Mandate, met in the Tel Aviv Museum on Rothschild Boulevard in Tel Aviv. -

Pirchei Agudas Yisroel of America

בס״ד בס״ד Learning from our Leaders Pirchei Agudas Yisroel of America RavOne Ben time Tzion R’ SegalAbba Shaulneeded was to thego Rosh Yeshiva As they approached their assignedRabbeinu! seats... in Yeshivatto Gateshead Porat withYosef his in son. Yerushalayim. One Someone accidentally afternoon Rav Mutzafi approached him with an padlocked the kitchen door emergency while he was learning. Tatty, but that’s I can’t learn Pesach,with please all the food for tonight’s PIRCHEI Two Adult 2nd cost so much more… hmm that small with this let’s movemeal. to How are we going to class tickets especially for 2 Agudas Yisroel of America boy easily could noise. the first classfeed our 120 hungry Vol: 6 Issue: 18 - י"א אדר א', תשע"ט - please. pass as a child… compartment. Bachurimadults!? February 9, 2019 פרשה: תצוה הפטרה: אתה בן אדם... )יחזקאל מג:י-כז( !!! eyi purho prhhkfi t canjv!!! nrcho tsr nabfbx tsr דף יומי: חולין פ״א מצות עשה: 4 מצות לא תעשה: 3 TorahThoughts was during this time, but מ ֹ ׁשֶ ה There are differing opinions as to where) וְעָשִׂ יתָבִׂגְדֵ יקֹדֶ ׁש לְאַ הֲרֹן ... לְכָבֹודּולְתִׂ פְאָרֶ ת)ׁשְ מֹות כח:ב(. Immediately Rabbi Abba Shaul took all The trainMoshe, attendant Chaim, Don inexplicably and Yosef! did You It is worthwhile to your , אַ הֲ ֹר ן the money he had out of his pocket. allnot can show share up into the collect privilege tickets. of a special And you shall make garments of sanctity for spend extra money for he certainly was not in Egypt.) mitzvah. -

View December 2017

TThehe ViewViewView December 2017 Annual Golf Cart Parade More Information on Page 34 Photo by Veronica Moya CONTACT INFORMATION SUN CITY SHADOW HILLS Sun City Shadow Hills Community Association COMMUNITY ASSOCIATION 80-814 Sun City Boulevard, Indio, CA 92203 www.scshca.com · 760-345-4349 Hours of Operation Association Office Homeowner Association (HOA). Ext. 1 Monday – Friday · 9 AM – 12 PM, 1 – 4 PM Montecito Clubhouse Fax . 760-772-9891 First Saturday of the Month · 8 AM – 12 PM Montecito Clubhouse . Ext. 2120 Montecito Fitness Center . Ext. 2111 Lifestyle Desk Daily · 8 AM – 5 PM Santa Rosa Clubhouse Fax. 760-342-5976 Santa Rosa Clubhouse. Ext. 2201 Montecito Clubhouse Shadow Hills Golf Club South . Ext. 2305 Daily · 6 AM – 10 PM Shadow Hills Golf Club North . Ext. 2211 Montecito Fitness Center Shadows Restaurant . Ext. 2311 Daily · 5 AM – 8 PM Jefferson Front Gate (Phases 1 & 2) . 760-345-4458 Santa Rosa Clubhouse Avenue 40 Front Gate (Phase 3) . 760-342-4725 Daily · 5 AM – 8 PM Rich Smetana, General Manager Shadows Restaurant [email protected] . Ext. 2104 Monday – Sunday · 8 AM – 8 PM Tyler Ingle, Controller Breakfast: 8 – 11 AM [email protected]. Ext. 2203 Lunch: 11 AM – 5 PM Mark Galvin, Community Safety Director Dinner: 5 PM – 8 PM [email protected] . Ext. 2202 HAPPY HOUR: 3 – 6 PM Jesse Barragan, Facilities Maintenance Director Montecito Café [email protected] . Ext. 2403 8 AM – 2 PM Connie King, Lifestyle Director Santa Rosa Bistro [email protected] . Ext. 2124 6 AM – 3 PM Valeria Batross, Fitness Director Golf Snack Bar [email protected] . -

Dear Youth Directors, Youth Chairs, and Youth Leaders, NCYI Is Excited to Continue Our Very Successful Parsha Nation Guides

Dear Youth Directors, Youth chairs, and Youth Leaders, NCYI is excited to continue our very successful Parsha Nation Guides. I hope you’re enjoying and learning from Parsha Nation as much as we are. Putting together Parsha Nation every week is indeed no easy task. It takes a lot of time and effort to ensure that each section, as well as each age group, receives the attention and dedication it deserves. We inspire and mold future leaders. The youth leaders of Young Israel have the distinct honor and privilege to teach and develop the youth of Young Israel. Children today are constantly looking for role models and inspirations to latch on to and learn from. Whether it is actual sit down learning sessions, exciting Parsha trivia games, or even just walking down the hall to the Kiddush room, our youth look to us and watch our every move. It’s not always about the things we say, it’s about the things we do. Our children hear and see everything we do whether we realize it or not. This year we are taking our Youth Services to new heights as we introduce our Leadership Training Shabbaton. This engaging, interactive shabbaton will give youth leader’s hands on experience and practical solutions to effectively guide your youth department. Informal education is key. What the summer shows us as educators is that informal education can deliver better results and help increase our youth’s connection to Hashem. More and more shuls are revamping their youth program to give their children a better connection to shul and to Hashem. -

Israel Prize

Year Winner Discipline 1953 Gedaliah Alon Jewish studies 1953 Haim Hazaz literature 1953 Ya'akov Cohen literature 1953 Dina Feitelson-Schur education 1953 Mark Dvorzhetski social science 1953 Lipman Heilprin medical science 1953 Zeev Ben-Zvi sculpture 1953 Shimshon Amitsur exact sciences 1953 Jacob Levitzki exact sciences 1954 Moshe Zvi Segal Jewish studies 1954 Schmuel Hugo Bergmann humanities 1954 David Shimoni literature 1954 Shmuel Yosef Agnon literature 1954 Arthur Biram education 1954 Gad Tedeschi jurisprudence 1954 Franz Ollendorff exact sciences 1954 Michael Zohary life sciences 1954 Shimon Fritz Bodenheimer agriculture 1955 Ödön Pártos music 1955 Ephraim Urbach Jewish studies 1955 Isaac Heinemann Jewish studies 1955 Zalman Shneur literature 1955 Yitzhak Lamdan literature 1955 Michael Fekete exact sciences 1955 Israel Reichart life sciences 1955 Yaakov Ben-Tor life sciences 1955 Akiva Vroman life sciences 1955 Benjamin Shapira medical science 1955 Sara Hestrin-Lerner medical science 1955 Netanel Hochberg agriculture 1956 Zahara Schatz painting and sculpture 1956 Naftali Herz Tur-Sinai Jewish studies 1956 Yigael Yadin Jewish studies 1956 Yehezkel Abramsky Rabbinical literature 1956 Gershon Shufman literature 1956 Miriam Yalan-Shteklis children's literature 1956 Nechama Leibowitz education 1956 Yaakov Talmon social sciences 1956 Avraham HaLevi Frankel exact sciences 1956 Manfred Aschner life sciences 1956 Haim Ernst Wertheimer medicine 1957 Hanna Rovina theatre 1957 Haim Shirman Jewish studies 1957 Yohanan Levi humanities 1957 Yaakov -

Download PDF Catalogue

F i n e Ju d a i C a . pr i n t e d bo o K s , ma n u s C r i p t s , au t o g r a p h Le t t e r s , gr a p h i C & Ce r e m o n i a L ar t in cl u d i n g : th e Ca s s u t o Co ll e C t i o n o F ib e r i a n bo o K s , pa r t iii K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y th u r s d a y , Ju n e 21s t , 2012 K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 261 Catalogue of F i n e Ju d a i C a . PRINTED BOOKS , MANUSCRI P TS , AUTOGRA P H LETTERS , GRA P HIC & CERE M ONIA L ART ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, 21st June, 2012 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, 17th June - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, 18th June - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Tuesday, 19th June - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Wednesday, 20th June - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No Viewing on the Day of Sale This Sale may be referred to as: “Galle” Sale Number Fifty Five Illustrated Catalogues: $38 (US) * $45 (Overseas) KestenbauM & CoMpAny Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . -

2015 Contents the Leicestrian 2015 Contents the LEICESTRIAN 2015

The 2015 Contents The Leicestrian 2015 Contents THE LEICESTRIAN 2015 INTRODUCTION 2 SCHOOL-WIDE EVENTS 4 ART 16 6th Form Writers & Interviewers CLASSICS 25 DEBATING 29 Harrison Ashman Joshua Baddiley Dominic Clearkin Rosie Gladdle Mary Harding-Scott Samantha Haynes ENGLISH & DRAMA 35 FOUNDATION DAY ESSAYS 46 Isobelle Jackson Rhona Jamieson Mohini Kotecha Harvey Kingsley-Elton Priya Luharia Holly Mould HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY & RS 52 ICT AND DT 64 Fathima Mukadam Lauren Murphy William Osborne Kirath Pahdi Sarah Saraj Elise Walsh MODERN LANGUAGES 66 MUSIC 73 POETRY 77 SCIENCE & MATHS 80 SPORT 88 1 The Leicestrian 2015 Introduction A Word from the Headmaster C.P.M. KING Selecting my favourite once again I find myself on the proverbial horns of a city presents me with dilemma. Should I choose the dramatic setting of Sienna, a real challenge. the unique Venice, the cities of the North or South? In As a geographer I’m the end it has to be Rome, because of its history and tempted to say it will architecture and because if you love life you can sit in be the next one I’m the Piazza Navona and watch the Italians enjoying their going to visit, which lives. I commend this edition of The Leicestrian to you as in my case is Istanbul. a comprehensive record of the past year and as a jolly However, I suspect good read. I thank all who have worked hard to shape this is not quite in the this edition and I hope you will enjoy it as much as I spirit of the excellent have enjoyed observing the events which this publication initiative designed to showcase creative writing in the records in its pages. -

Maspidim Remember Klal Yisroel's Rebbe, the Novominsker Rebbe

Maspidim Remember Klal Yisroel’s Rebbe, The Novominsker Rebbe April 29, 2020 See the recording of the azkarah below. By: Sandy Eller Harav Elya Brudny, Rosh Yeshiva, Mir Yeshiva and Chaver Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah 22 days later it still seems impossible to believe. As Klal Yisroel continues to mourn the loss of the Novominsker Rebbe, Rabbi Yaakov Perlow ztvk’l, Rosh Agudas Yisroel, chaverim of the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah and family members offered deeply emotional divrei hesped for a leader who was a major guiding force for Torah Jewry in America for decades. With state and local laws still in effect prohibiting public gatherings, maspidim addressed an empty beis medrash at Yeshivas Novominsk, an audience of nearly 60,000 listening through teleconference and livestream as the Novominsker was remembered as Klal Yisroel’s Rebbe. Normally echoing with exuberant sounds oftalmidim learning Torah, the yeshiva’s stark emptiness was yet another painful reminder of the present eis tzarah that has devastated our community. Rabbi Zwiebel waiting at a safe social distance while others were speaking. Throughout the over two hour-long azkarah, Rabbi Perlow was lauded for his unwavering devotion to Klal Yisroel, somehow stretching the hours of each day so that he could immerse himself in his learning and still give his undivided attention to the many organizations and individuals who sought his guidance. In a pre-recorded segment, Rabbi Shmuel Kamenetsky, Rosh HaYeshiva, Talmudical Yeshiva of Philadelphia, described the Rebbe as a “yochid b’yisroel” who cared so deeply for others that their needs became his. No communal issue was deemed too large, too small, or beyond the Novominsker’s realm of expertise, his sage counsel steering Klal Yisroel through turbulent waters when communal institutions such asbris milah, shechitah and yeshiva curriculums were threatened by public officials.